My body was draped head to toe in black, but I still felt naked. I have spent years living and working in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, yet now, for the first time, I was alone on a secluded street near the Red Sea, unescorted in public after sundown. Across the road, cab drivers in loose white robes squatted against a concrete wall, smoking cigarettes and eyeing me with open interest. I set my face with practiced indifference as I glanced quickly up and down the street. Then I saw them: two dozen women power walking, their limbs synchronized in the grainy yellow glow from the streetlights.

Out front was May Aboulfaraj, a forty-year-old fashion designer. In lieu of the other women’s traditional black abayas, she wore a custom jumpsuit made of lightweight purple cloth and decorated with reflective tape and iron-on emoji decals. As she waved to me, her sleeves fanned out, creating the silhouette of a flying squirrel. The tip of her ponytail danced beneath a green bandanna—a sporty substitute for a hijab. She greeted me with a brisk kiss on the cheek. “You missed warm-up! Yalla, let’s go.”

Aboulfaraj founded Bliss Run, a women’s running club, with three other women in 2016. Her collaborators, also in their forties or fifties, were dressed in their own custom jumpsuits. They welcomed me warmly. “Salaam, hi-hi habibti, love. How-are-you? Are you fine? Yeah? Amazing, alhamdulillah.” The women kept up a playful mood, but the gathering was an act of defiance.

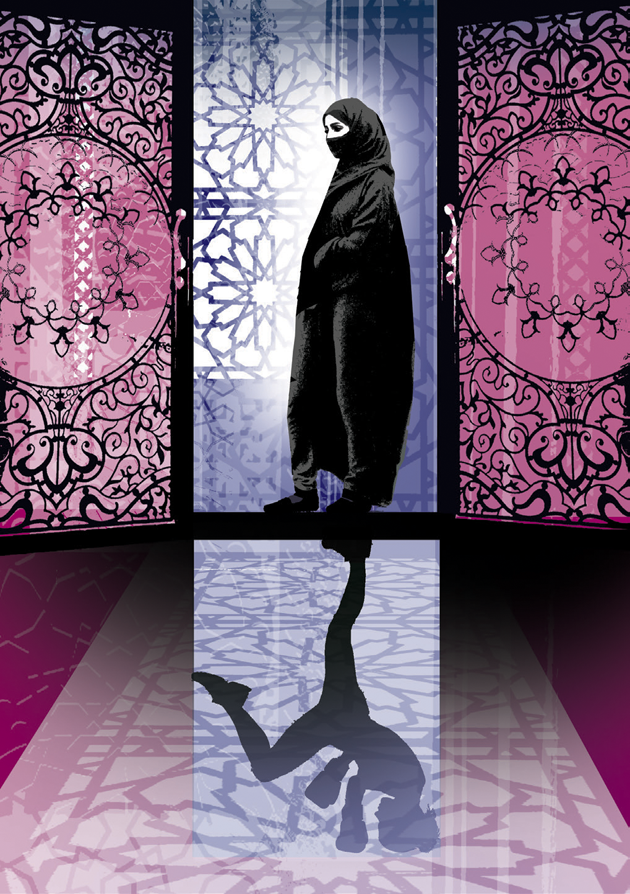

In Saudi Arabia, where women’s activities are restricted by a complex set of laws and informal rules, the sidewalk is the domain of men. Women are mostly relegated to domestic, indoor spaces, and when they do go out in public, they wear loose abayas that fully cover the body. Nearly all women—including me—cover their hair, and many screen their faces with full veils. Buildings that serve both sexes, such as banks and mosques, typically maintain separate entrances, while restaurants partition men from women and families. Offices sometimes have separate rooms to accommodate a single female employee. Many families also adhere to the Islamic concept of mahram, which stipulates that women be escorted by a male chaperone while in public.

Under Saudi law, women are dependent on a wali, a male guardian, from birth to death. The wali, usually a woman’s father, husband, brother, or adult son, has the power to deny her access to travel, medical care, and marriage. Doctors, landlords, and potential employers often demand a wali’s documented approval before they will interact with a woman. In the eyes of the Saudi state, women—who could not vote in municipal elections until 2015 and whose testimony in court is granted half the value of a man’s—are minors.

While many women (and some men) privately decry this system, resistance is often dangerous. The Saudi government is known to punish women for behavior that threatens arf, the traditional way of life: in 2016, police arrested several women for attending a mixed-gender party, and in July, a woman was arrested after a Snapchat video was posted of her walking in public without an abaya. The Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, an organization founded in the 1920s by the first king of Saudi Arabia, has thousands of enforcers, called muttawa, who patrol public spaces to ensure adherence to strict religious rules. The muttawa curtail ikhtilat, or the “mixing” of genders, and crack down on such transgressions as nail polish, improperly positioned headscarves, and audible laughter. Officially, the CPVPV is supposed to defer to the police, but the group has committed innumerable human rights violations—including chasing, beating, and unlawfully detaining women—and has proved impervious to reform. In 2016, after a string of incidents of abuse by CPVPV officers were documented by human rights groups and local media, the government attempted to limit the committee’s power, imploring its officers to act more “kindly and gently.” But the CPVPV continues to receive generous government funding, and after a brief quiet spell they resumed many of their hard-line tactics.

The latitude granted to the CPVPV is symptomatic of the ambiguity in Saudi law: the kingdom has no formal constitution. Instead, the monarchy cites the Koran and the Sunnah—the traditions of Prophet Mohammed—as its fundamental law. Many issues, including civil rights, are left to the discretion of the ulema, or Islamic scholars. Historically, most of the ulema have favored punitive interpretations of Islam, steering the government toward authoritarian policies. Over the years, activists calling for a formalized constitution have been subjected to imprisonment for their “un-Islamic” ideas and disrespect of the monarchy.

For decades, activists who lobbied to lift the ban on women driving faced similar punishments, and their campaign became synonymous with the supposed hopelessness of the feminist cause in the kingdom. But this past September, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud made a surprise announcement: he would lift the ban in June 2018. In the meantime, the government would assemble a task force to work out the specifics.

The news signaled an unprecedented commitment to progressive change. Soon after, the king’s son Mohammad bin Salman Al Saud, a thirty-two-year-old newcomer to the political scene, vowed to return the country to “moderate” Islam. In 2016, he had announced a plan called Vision 2030, an ambitious economic campaign touting an array of social reforms. Although his priority is diversifying the economy—50 percent of the country’s GDP currently depends on oil and gas—the crown prince has said that he also aims to increase women’s participation in the workplace, foster national cultural pride, and improve public health. To address the latter, he established an office for women and sports. Princess Reema bint Bandar Al Saud, an entrepreneur and philanthropist with no previous political experience, was appointed its leader. Overnight she became the highest-ranking woman in government.

The existence of a government office, however, made little immediate difference in the cultural perception of women’s athletics—something I felt keenly as the members of Bliss and I approached the starting line for the night’s run. A family sitting on the ground sharing a thermos of tea stared; the man, lounging barefoot in a white thobe, leaned up on his elbow to get a better look as his wife, a cross-legged pyramid of black cloth, pivoted to watch us pass. Aboulfaraj told me that Bliss was inspired by her travels abroad, where she saw women exercising outdoors freely. “I wished to see the day that the same could happen in Saudi,” she said, “that women could go outside without any shame or discomfort or strange looks.” But when she’s recruiting members around Jeddah, she said, most women initially find the idea of running in the street unthinkable.

When it was time to begin the run, Aboulfaraj turned to face the pack of women, her soft voice suddenly commanding. “Ladies!” she said. “Get ready to push yourselves! Trackers ready!” This was the cue for us to take out our smartphones and open an app that recorded speed and distance. “And—let’s go!” The runners tapped a green button on their screens and a chorus of robotic voices declared, “Starting workout.”

The group splintered quickly. Aboulfaraj and her colleagues, nimble in their custom jumpsuits, wove through the crowd to assist the others. The women in abayas struggled to keep from tripping over the long hems; Hala, a plump, middle-aged housewife, avoided this by cinching hers around her waist, revealing calves sheathed in black leggings. My abaya allowed me only short, shuffling steps, but I nevertheless drifted toward the front. A layer of muggy heat thickened between my skin and the polyester folds. My headscarf kept slipping down. I felt grateful that it was February, and a modest, if humid, 72 degrees. Summer temperatures can exceed 120.

We passed dusty date palms, patches of dry grass, and Arabic signposts admonishing us remember allah and there is no god but allah. A few male joggers in shorts and T-shirts passed in the opposite direction. One tossed a suggestive comment our way—“Will you come run with me?”—but most of them averted their eyes.

Five minutes in, half of the women slowed to a walk, and Aboulfaraj stayed back to encourage them. I caught up to Bodoor, a slender woman in her midthirties. She checked the app repeatedly, murmuring her pace to herself. When we reached an intersection, Bodoor ran into the street without breaking stride, holding out her palm to halt the bewildered drivers. At the row of orange cones that marked the finish line, she continued to jog in circles, glancing at her phone. “Not even two kilometers,” she muttered with a self-deprecating smile. The other runners, however, approached the finish line with pride. Some of the women’s first runs had lasted just thirty seconds, but after six months with Bliss, they had built their endurance to eight or nine minutes. As the rest of the group trickled in, I heard a sound that I’d never encountered on a Saudi street: cheering female voices.

It was almost ten o’clock by the time I returned home, to the apartment of Umm Musa, a family friend. She met me at the door dressed in a loose robe and light-pink headscarf, her brow furrowed behind wide-framed glasses. As I peeled off my abaya, she began chiding me. “Ya bint! Girl, what are you doing out all night? Who drove you back?” Smiling, I explained Uber to her for a third time. She shook her head. “Not safe!”

Umm Musa pulled me down the hall and into a windowless, sponge-painted sitting room. Her husband, Mohammed, a stocky contractor with a salt-and-pepper beard, dozed in front of a muted television. Small tables heaped with dates and sugar-dusted cookies were within arm’s reach of every seat. Umm Musa drew up one of the tables, cleared away the sweets, and set two plates of food in front of me—I had missed both lunch and dinner, so she’d saved me some of each.

She resumed her interrogation. When I explained that I’d been out running with a group of Saudi women, Umm Musa’s eyes widened. “They’re doing what?” She frowned as I described the jumpsuits, the makeshift hijabs, the dim, secluded route. I reminded Umm Musa that she often complained about being stuck at home—just the day before she had expressed worry about her weight. She placed a hand on her ample belly and sighed. “Yes,” she said. “I do need some movement in my life.”

Umm Musa has never worked outside her home and, apart from grocery trips twice a month with Mohammed, seldom leaves her second-story apartment. Her life is organized around Friday lunches, when any number of her eight children and twenty-seven grandchildren might crowd into the apartment to feast. During the week, she fills solitary hours chatting with family on WhatsApp, watching soap operas, and preparing dinner. She naps too. And snacks. In recent years she’s slowed down considerably; her stiffening joints and increasing weight leave her reliant on a live-in housekeeper. Still, Umm Musa tries to downplay concerns about her health, joking that she has dem khafeef—“light blood,” or good humor.

Her doctor feels differently. Umm Musa is five foot two, and her weight fluctuates between 170 and 190 pounds, putting her somewhere between “overweight” and “obese.” She is at risk for diabetes and osteoporosis, and her blood pressure is well above the healthy range.

Umm Musa’s case is alarmingly typical: Saudi Arabia has seen a surge in obesity and related illnesses over the past few decades, and today 70 percent of the total population is overweight. Yasmin al-Twaijri, an epidemiologist at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in Riyadh who is one of the nation’s leading obesity researchers, attributes this trend to the usual changes that accompany modernization: labor-saving technology, sedentary daily routines, and an abundance of cheap processed foods. (In Saudi Arabia, McDonald’s delivers.) Among the middle and upper classes, the problem is compounded by the country’s two-tiered economy, in which most physical labor is shunted onto migrant workers.

Though many Western countries are also experiencing accelerating obesity rates—Americans overall are just as overweight as Saudis—the crisis in Saudi Arabia is uniquely determined by gender. According to al-Twaijri, the usual causes of obesity combined with the many restrictions on women act as a “double whammy.” A 2015 study found that 75 percent of Saudi women do little to no physical activity, compared with 46 percent of men, and the rate of obesity among women is about twice that of men. “Saudi Arabia is really a special case,” al-Twaijri told me. “Lack of exercise is literally killing women.”

Female sedentariness is a deliberate result of policy. Vilifying women’s physical activity has long been a pet cause of hard-line conservatives. In 2012, when Saudi officials first permitted female athletes to take part in the Olympic Games (in response to pressure from the international committee), detractors called the two who competed “prostitutes of the Olympics,” citing the impropriety of traveling abroad and putting their bodies on display. In 2014, Abdullah al-Dawood, a conservative author with nearly one hundred thousand Twitter followers, warned that allowing girls to participate in fitness and sports was a product of “Westernization” and would lead to “infidelity and prostitution.” Sheikh Abdullah al-Maneea, a member of the Supreme Council of Religious Scholars, has said that allowing virgins to exercise is dangerous, claiming that activities like running and jumping cause damage to the hymen.

As I finished my kebab with Umm Musa, Mohammed roused himself. “Women are always worried about getting fat,” he said, chuckling. “Of course my wife is fat—she doesn’t do anything!”

Umm Musa grinned and swatted away his comment with a gold-bangled arm. “I do more than you, ya sheikh!” She reminded Mohammed that he had grown heavier over the years, too.

“Alhamdulillah, praise God,” he replied, thumping his belly in an unconscious imitation of his wife.

On occasion, Umm Musa would suggest that they take a daily walk at the edge of their neighborhood. “I used to try to exercise, a little bit,” she said. “But I don’t like the way men looked at me, sometimes shouted at me. And Mohammed doesn’t want to walk with me.”

Mohammed sniffed. “It’s too hot,” he said, reaching for the TV remote.

Umm Musa shrugged and pointed at the platter of rice in front of me. “Eat, ya bint.”

There are hundreds of men’s gyms throughout Saudi Arabia, including international chains such as Fitness Time and Gold’s Gym, but the government has for years refused to make permits available for gyms that serve women. In the past decade, however, an underground network of unlicensed fitness centers has appeared, led by female athletes and trainers. By 2016, there were about a hundred of these illicit gyms in the kingdom, ranging from multistory enterprises officially registered as “retail shops” to makeshift basement studios advertised only on social media or by word of mouth.

One of the best-known figures in the underground fitness scene is Halah al-Hamrani, a forty-year-old kickboxing instructor who started her company, Fight Like a Girl Boxing (FlagBoxing), out of her parents’ pool house in 2003. Since then, it has grown into a full-time operation with a $60,000 studio, a line of athletic clothing, and 20,000 Instagram followers. “For a long time, the market for women’s fitness here was really small,” she told me. “It’s just the past three, four years that things have started to blow up.” Al-Hamrani is aware that with a growing clientele comes the risk of government scrutiny; for other women’s gyms, that attention has forced them to close.

I met al-Hamrani on a weekday afternoon at her studio in Jeddah, which she runs out of a ground-floor apartment that has tinted windows and a camera-equipped buzzer. She opened the door in bare feet and cutoff sweatpants, her hair swept up in a frizzy ponytail. I followed her to a large workout area outfitted with imported CrossFit rigs, ten punching bags, and half a dozen benches. Mirrors covered every wall. A set of gymnastics rings dangled from the ceiling.

“Sports have always been my lifeline,” al-Hamrani told me as she arranged free weights for that afternoon’s class. In school, she struggled with ADHD, but exercise gave her confidence and joy. As the child of an affluent businessman, al-Hamrani was able to enroll in private gymnastics, dance, and martial arts lessons taught by expats in gated compounds. Her experience was unusual—physical education for girls has been prohibited in the public school system since the Ministry of Education first expanded to include female students in 1960. At eighteen, al-Hamrani left to attend the University of California, San Diego, where she joined the women’s rowing team. Later, she began practicing CrossFit. After graduation, when she returned to Jeddah and struggled to find a job, her mother suggested that she try personal training. “It was the one thing that I really loved, and she thought maybe I could make a business of it,” al-Hamrani said. She bought a few free weights and a punching bag and started teaching kickboxing to friends.

When she began coaching, al-Hamrani was struck by how many of her clients lacked basic physical coordination and strength. Some struggled to do a single push-up. “Think about it: for the first thirty, forty years of their lives, they never moved their bodies, so lots of them have no muscle memory, no sense of balance.” She now has about a hundred clients and coaches several classes each day. A drop-in session costs 250 riyals ($60), which she admits is expensive. “I am in a bit of a bubble,” she told me. “I mostly get the more educated, wealthy Saudis. Those are also the ones who are accepting of who I am, as a woman athlete.”

The afternoon session I attended was sold out, with ten students between the ages of seventeen and forty-five. They arrived in private cars and discarded their abayas in lockers by the door, revealing pastel leggings and pristine sneakers. Al-Hamrani clapped her hands. “Positions!” The women arranged themselves into two rows. The workout, al-Hamrani explained, would rotate through eight exercises that included floor ladders, burpees, bear crawls, and punching combos. With a remote, she set a digital timer on the wall. “Three minutes on, one minute off—go!”

For the next forty minutes, al-Hamrani monitored us carefully, wielding a PVC pipe, scepterlike, to correct breaches of form. “There,” she said to me when I tried to skimp on my lunges, tapping a spot farther out on the floor. Sondos, a cheerful, overweight consultant in her late twenties, sprinted in a tight loop, gasping for breath. But her reward was sweet: at the end of the interval, al-Hamrani gave a single nod and said, “Yes.”

When the final timer rang, Sondos flopped onto a mat, laughing, her long hair fanning across the floor. She had started at FlagBoxing eight months earlier in an effort to lose weight, but the classes soon became a kind of therapy. Now she came to al-Hamrani’s studio every day. “I need the endorphins so bad,” she told me. “I was really unhappy. My life was just work, home, stress, and I was gaining more and more weight. Now I have an outlet, something to look forward to at the end of the day.” She waited until her sweat dried enough for her to pull on her abaya, then headed toward the door. “See you tomorrow!” she said. Al-Hamrani gave a mock salute.

After everyone left, al-Hamrani pulled up a bench across from me. Seated, her body remained in motion, the white sneakers she wore during class tapping the rubber floor. Interest in women’s fitness has become mainstream in the Middle East, she said, and multinational companies have picked up on the new market. Last year, al-Hamrani was approached by Pepsi to be featured in an ad alongside Amal Baatia, a Saudi female CrossFit coach, and several high-profile male athletes. Nike recently launched an athletic hijab. Her business, she sensed, could expand dramatically—as long as she could protect it from the hard-liners.

Al-Hamrani doesn’t identify as an activist, but in a country where women’s bodies are routinely treated with contempt, creating a space for women to exercise becomes an affirmation of their right to physical health and pleasure. “I’m proud of these girls,” she said of her students. “These women are tough, strong. They have some real frustrations to punch out.” She smacked a fist into her open palm. “You know how it is, for women here.”

One afternoon, I flew to Riyadh to meet Princess Reema, the head of women’s and community sports for the General Sports Authority (GSA), at her home. Beyond a long driveway, an expansive garden, and clusters of luxury cars, the villa’s white walls glowed pink in the fading sunlight. Inside, a butler showed me to an airy sitting room. Cupcake, the princess’s cat, joined me, curling up into my lap and covering my abaya with tufts of orange fur.

After a moment I was shown into Reema’s office. The princess, who is forty-two, was wearing a business skirt, a navy blouse, and black heels. She stood over a table stacked with papers, deep in discussion with a senior member of the Saudi Arabian Olympic Committee. After he left the room, she exhaled and flashed me a smile. “Do you mind if I take off my shoes and put on my slippers?” She gestured to a pair of cream-colored, woolly slip-ons next to her chair. “I’ve been an adult all day, and I need to put on my slippers before I cry.”

Even in slippers, Reema exuded poise. She speaks English with an easy fluency, polished by years of living in the United States as the daughter of the kingdom’s ambassador. Before entering the government, she was the head of the luxury department store Harvey Nichols’s franchise in Saudi Arabia, where she hired first-time female workers and advocated publicly to advance women seeking careers. (Although a growing minority of Saudi women have taken jobs outside the home, they account for only about 20 percent of the workforce, despite making up more than half of the nation’s university students.) Reema caught the attention of senior officials in 2015, when she led a breast cancer awareness campaign that culminated in a thirteen-thousand-woman rally in Riyadh, setting a Guinness world record for the largest “human ribbon.”

At the time of Reema’s appointment to the GSA, none of the more than 150 sports clubs and thiry-two federations it oversaw included women. In her first year, Reema managed to push an impressive number of reforms through Saudi’s cumbersome bureaucracy, including monetary incentives for clubs to admit women and disabled athletes. Since then, several federations, including those of golf, fencing, and tennis, have added female members.

Most notably, Reema persuaded the ministry of education to start a physical education program for girls. PE has a long and fraught history in Saudi politics; in the gender-segregated public school system, which serves 85 percent of the country’s children, boys attend gym class several times a week, yet girls have been forbidden on religious grounds. In 2015, Nora al-Fayaz, a former deputy minister of education, was fired in what many saw as retribution for her outspoken advocacy for girls’ gym classes. Reema’s victory was unexpectedly smooth. The brief statement the ministry released in July about the new PE program did not specify which activities would be deemed appropriate, however, and it remains to be seen what forms these classes will take. Considering the absence of fitness facilities in girls’ schools and the lack of qualified female instructors, it may take many years for the programs to be conducted at a standard equivalent to boys’ PE.

This past summer, Reema scored her most significant victory. Perhaps recognizing the gravity of its obesity crisis—and the expense; all Saudi citizens receive free health care—the government launched an online license-application system for gym owners. Because of Reema’s lobbying efforts, for the first time, licenses would be made available to fitness facilities for women.

So far, thirty-two women’s gyms have been approved. Leejam Sports Company, the largest operator of men’s gyms in the kingdom, plans over the next six years to open about a hundred facilities for women, which they expect will attract hundreds of thousands of new members. Reema predicts that “a cascade of new jobs” will be created as the athletics sector is expanded to include women in sports medicine, sports merchandising, and personal training. She also believes that the proliferation of gyms will lead to future generations of elite female athletes. “I’d like to see Saudi women actually competitive at the Olympic Games one day,” she said. At the 2012 London Games, having trained without institutional support, Saudi Arabia’s two female athletes performed dismally: Sarah Attar finished the 800-meter dash dead last, and Wojdan Ali Seraj Abdulrahim Shahrkhani was eliminated from the judo competition in the first round. Attar returned in 2016 to compete in the marathon event, and placed 132nd out of 133 runners.

While the licensing reform will likely make exercise more accessible overall, there are signs that it will be used to increase government monitoring of women’s activities. The GSA’s guidelines make no mention of gender-specific restrictions in gym services, but in Saudi Arabia, ambiguities in legal texts often become openings for conservative interpretations. Religious authorities could push to have certain activities—such as martial arts, yoga, and dance—banned for women. At a wellness and fitness event hosted by the GSA in honor of International Women’s Day, the yoga and Zumba workshops were canceled at the last minute. Officials cited a “technicality” in the group’s permit application, but several women involved told me they believe the decision was made on religious grounds.

When I asked Reema about potential constraints on women’s fitness centers, she was noncommittal. “We don’t need to create endless rules,” she said. “I want to create opportunities. The market will decide what is right for each community. For example, I would never build an outdoor track for women without building a wall around it, because I know women won’t come if they feel exposed.” (This was the architectural solution for the basketball court of Jeddah United, one of the few private club sports teams for women—the court is surrounded by high concrete walls.)

Reema’s diplomatic approach to pursuing individual freedoms for women enables gradual cultural change, but leaves the structure of patriarchal control intact. I asked her whether she considered herself a feminist. “No. I’m an active woman, not an activist,” she quickly replied. “It’s a good time to be a Saudi woman.” After a moment, she added, “I’m speaking first and foremost on the level of sports and fitness. In this arena, doors are opening very quickly for women. And what I’m hoping is that that will then have an impact on the doors that aren’t open yet.”

Her unwillingness to publicly address the broader social conditions of women is understandable, if unsatisfying. In Saudi Arabia, little is truly decided in the public sphere—policy reversals, as with the driving ban, can occur overnight as a result of inscrutable machinations.* “I know some Saudi women are cynical about me, but we are trying to accomplish real change,” she said. “I just hope they can be patient.”

Later, I asked al-Twaijri what she made of Reema’s efforts. Though her intentions are admirable, she told me, it would take more than a few reforms to reverse the damage done by years of discrimination and sedentariness. “It’s great to have more gyms. But there’s a huge population of women who aren’t going to go there. It’s not a habit for them to be active, and for some it feels like an uncomfortable space.” She continued, “We have to think of the entire social ecosystem. We have to change our cities and towns.”

Back at home, I wanted to know: Would Umm Musa consider joining a gym? She snorted into her tea. “I don’t think that kind of thing is for old, heavy women like me.”

In September, al-Hamrani sent me a photo of a young girl dangling upside down from a bungee cord, her long braid skimming the floor. Other pictures showed girls doing cartwheels and swinging from monkey bars. They were participating in a workshop as part of a soft opening for al-Hamrani’s new gym. Designed for kids aged three to sixteen, it will specialize in parkour, gymnastics, and a free-form choreography al-Hamrani calls animal movement. One of the first members is her eight-year-old son, Talal, a parkour and Muay Thai enthusiast. His dead hang lasts a full minute, and leaves his mother beaming.

When al-Hamrani learned of Reema’s push to license women’s gyms, she was skeptical. Fearing her business would be subjected to increased government scrutiny, she was in no rush to apply for legal standing, even at the risk of being fined.

Yet she is eager to keep expanding. “There is so much to be done in fitness right now,” she said. “This is the time to invest.” In October, al-Hamrani was invited to present her gym to investors at a Shark Tank–like event in Jeddah. Reema attended, and the two spoke about al-Hamrani’s concerns. With Reema’s assurance that her gym operations would not be restricted, al-Hamrani decided to pursue a license for FlagBoxing.

In another picture taken by al-Hamrani, a boy and girl who look to be about six years old hang side by side on the monkey bars, their small hands in an even line. Classes at al-Hamrani’s new gym are coed—virtually unheard of in Saudi Arabia, and technically unsanctioned. (The GSA does not license gyms or studios for children.) Mixed classes make better athletes, she told me. They allow young boys to relate to their female classmates, but the classes benefit girls especially: “It will make them tougher.” Growing up, al-Hamrani practiced jujitsu in coed classes taught by an expat couple, and sparring with male opponents, she believes, taught her to be a stronger and gutsier fighter. Her favorite part: throwing the men.