In the spring of 2017, for the first time since publishing a memoir set at the height of San Francisco’s AIDS epidemic, I summoned the nerve to teach a course on memoir—which is to say, at least as I taught it, a course on the necessity of personal witness, a course against forgetting. Mostly I avoided the subject of AIDS, not wanting to be the grizzled old veteran croaking war stories to a classroom of undergraduates. But since AIDS memoirs are among the best examples of the genre, I decided I had to foray into the minefields of those memories. I surprised myself by choosing not one of several poignant memoirs but the edgy anger of Close to the Knives, by the artist David Wojnarowicz, with its hustler sex and pickup sex and anonymous sex on the decaying piers of Chelsea and amid the bleak emptiness of the Arizona desert, one eye cocked at the rearview mirror to watch for the cop who might appear and haul your naked ass to the county jail, sixty miles of rock and creosote bushes distant.* Wojnarowicz was thirty-seven years old when he died of AIDS in 1992.

My students were fascinated by Wojnarowicz’s raw frankness. One student, a father of two, wrote that I had not provided enough context for the book, teaching me that this history-changing event, the brutality and horror of AIDS, was more foreign to my students than the Vietnam War, no matter that the disease is still among us, no matter that his ignorance will become his children’s ignorance, which may lead them to be the next generation of HIV-infected. One student asked, “But how did they organize—I mean, without social media?” So I showed documentary footage, the filmmaker’s version of memoir, activists coming together in raucous planning meetings to orchestrate the dumping of cremated ashes on the White House lawn or the carrying of a real dead body in an open coffin to the gates of the National Institutes of Health. In my students’ curious, discomfited eyes, I understood that I might have been showing films of creatures from another planet, so foreign was this notion of working together to achieve change.

And perhaps to them we were creatures from another planet—acting up, fighting back—so beaten down are they in the face of constant, implied threats of lifelong unemployment from universities and corporations, so balkanized are they by social media, so overwhelmed are they, in their early twenties, by the student debt with which we, their elders, have saddled them so as to leave them no time for introspection or collective action.

How can we read our politicians’ and university presidents’ drumbeat emphasis on STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) at the same time that they defund the arts and humanities as anything but pressure on faculties to train a docile pool of drones? Deans and professors promote the humanities as a training in critical thinking, but critical thinking leads to criticism, the last student activity university administrations want to encourage. I teach at such a public institution, the University of Arizona, where arts and humanities have sustained disproportionate cuts even as its Board of Regents, in executive session, recently hired a new president at a salary of just under $1 million annually, plus perks, while simultaneously raising tuition. Meanwhile, the university’s Freedom Center, founded with Koch brothers money, receives a special appropriation from the Republican-controlled state legislature.

Self-portrait of David Wojnarowicz, 1983–84, by David Wojnarowicz with Tom Warren © The Estate of David Wojnarowicz. Courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York City

Though I lived in San Francisco at the time, I did not join the ACT UP activists who blocked the Golden Gate Bridge; I stayed at my desk. Words, grammar, and syntax were my tools—small, stainless-steel wedges I would use to split readers’ breastbones so that I might tenderly lift out their beating hearts and display them to themselves, fully conscious, before restoring them, with equal tenderness, to their chest cavities and sewing up the wound. It is not my place to judge my success, but during those years my self-declared goal was to make a stone weep, because maybe the weeping of stones would bring about change, real change—would make us understand that we have no future in the rape of the world, that we have no future in dividing and subdividing into nations and clans and fortified mansions with manicured lawns and access codes, that we have no future except through love.

Leaving my last class of the semester, I encountered a student so lost in her texting, so oblivious to the living, breathing, gorgeous, fragile world, that had I not stepped aside she would have collided with me. For me, veteran of the AIDS era of terror and anger and heartbreak, her oblivion precipitated the past into the present. Not even Dante could have devised a punishment so perfectly suited to the crime: the use of a weapon, to quote Cornel West, of mass distraction; a device that, by robbing us of our need to remember, facilitates forgetting.

What we met and worked and marched and wrote and died for was radical transformation. What we settled for was marriage.

The LGBT assimilationists’ rise to power is easy to trace. The brave, righteously angry civil rights activists of the 1970s became the brave, righteously angry AIDS activists of the 1980s and early 1990s, but we died or lost ourselves to grief, and by the time the white coats figured out the cocktail, by the time the drugs healed instead of killed, the people they saved were shells of themselves, and all that the survivors had the energy to do was lie on the warm sands of Fort Lauderdale or by the pool in Palm Springs and contemplate the mystery of survival. The cocktail that turned HIV from a death sentence into a manageable illness was perfected in 1996; the assimilationists moved the battle for state-sanctioned marriage to center stage in national politics during that year’s presidential election.

In those early years, proponents presented same-sex marriage for what it was: a right-wing initiative whose goal was to enable the Republican grandparents of Peoria to feel comfortable inviting their grandchild’s same-sex lover to holiday dinners. At a forum on same-sex marriage held in the late Nineties at New York’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center, several architects and engineers of the initiative to single out the legalization of marriage as the principal—indeed, the only—issue of consequence for the LGBT community argued that the legalization of same-sex marriage was an essentially conservative undertaking. State-sanctioned marriage would tame an impassioned bunch of outlier renegades.

The crowd consisted almost entirely of white men; I saw only two black men in the audience. Afterward I approached one of the speakers to suggest that the demographics conveyed a message about the supporters and primary beneficiaries of same-sex marriage. He dismissed my observation as irrelevant, saying that such audiences always skewed male. But within the year the spin was changed, as evidenced by my encounter a couple of years later in San Francisco’s Noe Valley with two young, white, conventionally attractive lesbians, who brandished a clipboard and asked whether I was willing to sign a petition to “legalize love.” In two years, the pitch on same-sex marriage had gone from presenting it as a ticket to the status quo—the ultimate insiders’ club—to a way to enable otherwise conventional people to feel they were participating in the romance of revolution.

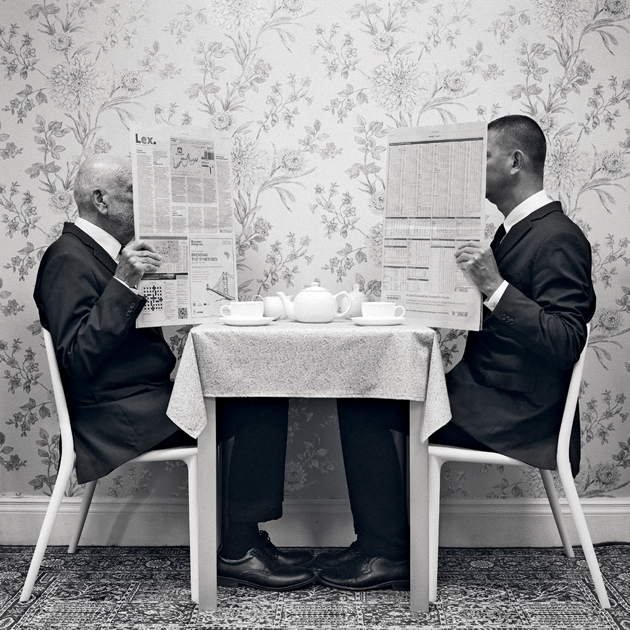

The assimilationists have won, with state-sanctioned marriage as the very mortar cementing the bricks of the wall of convention that separates us from ourselves, from one another, from all that is unfamiliar, strange, challenging, and thus from learning and growth. The assimilationists have won, with the neocons building their Wonder Bread philosophies upon the ashes of queers who laid their lives on the line in the fight for AIDS visibility and treatment. The assimilationists have won, those men and women whose highest aspiration was to be like everybody else, whose greatest act of imagination was picturing matching Barcaloungers in front of a flatscreen television and matching, custom-designed wedding rings.

The evolution from ACT UP and Zen Hospice to state-sanctioned marriage is precisely analogous to gentrification—the creative outliers do the heavy lifting, and when a certain level of safety has been achieved, the assimilationists move in, raise prices, and force out the agents of change. But while we recognize and make at least cosmetic efforts to address the darker aspects of gentrification, we have forgotten or marginalized the in-your-face, in-the-streets activists of the LGBT left. So long as we, the outliers, insisted that we had something to offer, that our world, where we formed enduring relationships outside the tax code and the sanction of church and state, where we created and took care of families of lovers and friends and strangers alike—so long as we insisted that this world was richer, more sustainable, more loving in so many ways than the insular world of Fortress Marriage, we got nowhere. Only when we exchanged our lofty ideals for conventionality was our struggle embraced. Only when we sought to exchange, in the words of the assimilationist attorney William Eskridge, “sexual promiscuity” for “the potentially civilizing effect” of state-sanctioned marriage were we accepted—as if a community risking their lives to care for their own in the face of church and government condemnation was not the very highest manifestation of civilized behavior; as if marriage “civilized,” to offer one of countless examples, Harvey Weinstein.

State sanction of same-sex relationships conveys certain privileges—I hesitate to call them rights—to a subset of the LGBT community even as it mimics mainstream discrimination by reinforcing a hierarchy of affection. Once, loving same-sex relationships served as an obvious critique of any necessary connection between love and marriage. Now the American Family Association and Lambda Legal are in agreement: serious relationships lead to marriage. Everything else is just playing around.

The legalization of same-sex vows is another step in the monetization of all human encounter. Under capitalism, love, like everything else that was once sacred, has become inextricably entangled with Social Security perks and property transfers and thirty-thousand-dollar weddings accompanied by prenuptial agreements written in anticipation of divorce. When its advocates spoke of marriage as a civil right, they were speaking not of love, which remains mercifully and always indifferent to the law, but of property—its smooth acquisition and tax-free disposition, the many advantages it affords, one might say, to the married.

Popular culture has always created and sustained an elaborate myth yoking love to marriage. Jane Austen, Henry James, and Zora Neale Hurston, to name three novelists who come effortlessly to mind, were not so gullible. In their novels, women are and understand themselves to be commodities and marriage the ultimate commodity transaction. Same-sex marriage extends that right, if it is such, to any couple willing to submit their hearts to the oversight of the law, though in the absence of the economic inequality imposed on women I struggle to understand why anyone undertakes such a course. André Gide, among the first openly gay writers, offered one clue—“The laws of mimicry,” he wrote in L’Immoraliste:

I call them the laws of fear. People are afraid to find themselves alone, and so don’t find themselves at all. . . . You can’t create something without being alone. . . . What seems different in yourself: that’s the one rare thing you possess, the one thing that gives each of us his worth; and that’s just what we try to suppress. [Instead] we imitate.

Writing in these pages more than twenty years ago, I predicted that “the extension . . . to same-gender couples of the marital status quo will represent a landmark civil rights victory but a subcultural defeat.” In my view that is precisely what has transpired. Now the lesbian in Lubbock can marry her partner, yes, but at the risk of losing her job and the roof over her head, since the backlash from the marriage victory has delayed indefinitely the passage of federal employment and housing protections for LGBT people—protections long supported by a majority of voters.

That there are exceptions to this rule—marriages I know, admire, and respect, in which spouses work to bridge the wall, engage with the community, invite solitaries into their lives—does not belie the predominance and glorification of Fortress Marriage as the norm: the married couple whose friends are all couples, who divide the world into inside and outside, who practice an intense, couple-centered version of collective narcissism. Why does this matter? Because our salvation, our literal salvation in the here and now, in this nation, on this planet, requires our abandoning those ancient clan divisions in favor of the understanding that we are all one. As the Buddha abandoned his family to undertake the search that led to enlightenment, so Jesus, that communitarian proto-feminist celibate bachelor Jew, rejected the ancient clan divisions in favor of a new order—Matthew 12:47–49:

While he was still speaking to the people, behold, his mother and his brothers stood outside, asking to speak to him. But he replied to the man who told him, “Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?” And stretching out his hand toward his disciples, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers!”

To turn the counterculture question on its head, can someone be gay without being queer? Someone who, to adapt the words of Roy Cohn in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, understands himself as a conventional man who fucks around with guys? Who puts what where is in fact important, not because of the obsessions of the homophobes and misogynists but because in sex the receptive partner is vulnerable, open, at greater risk. These, it turns out, are the essential qualities of love, the essential qualities of queer. And so what defines queer, finally, is not what one does in bed but one’s stance toward the ancien régime, the status quo, the way things have always been done, the dominant mode, capitalism.

Speaking with James Baldwin late in his career, a television interviewer remarked, “When you were starting out as a writer, you were black, impoverished, homosexual. You must have said to yourself, ‘Gee, how disadvantaged can I get?’?” To which Baldwin responded, “Oh, no, I thought I hit the jackpot! It was so outrageous, you could not go any further. So you had to find a way to use it.”

To be born bent, however that manifested itself, was once to be forced to look within—to explore and express, in Gide’s words, “what seems different in yourself.” This embrace of the gift of our essential difference was the wellspring of queer creativity—for evidence, read or look at Walt Whitman, Henry James, Sherwood Anderson, Carson McCullers, Tennessee Williams, Virginia Woolf, Gloria Anzaldúa, Marsden Hartley, Audre Lorde, Agnes Martin, Baldwin, Baldwin, Baldwin, to name only a few of the eminently civilized writers and artists who understood commitment as well as or better than any people taking marriage vows with the knowledge of no-fault divorce waiting in the wings. Their lifelong, selfless practice rooted itself in their fecund, uneasy difference: their queerness. These queer writers and artists took unbreakable vows to their art, dedicating their lives to showing us, their audience, the human condition. Through their art they showed us that the solitude we so fear, that we will do anything to escape, even marry—that solitude is an illusion, a scrim preventing us from seeing how we are all one, we are all in this boat together.

To be born bent, however that manifested itself, was once to be forced to look within—to explore and express, in Gide’s words, “what seems different in yourself.” This embrace of the gift of our essential difference was the wellspring of queer creativity—for evidence, read or look at Walt Whitman, Henry James, Sherwood Anderson, Carson McCullers, Tennessee Williams, Virginia Woolf, Gloria Anzaldúa, Marsden Hartley, Audre Lorde, Agnes Martin, Baldwin, Baldwin, Baldwin, to name only a few of the eminently civilized writers and artists who understood commitment as well as or better than any people taking marriage vows with the knowledge of no-fault divorce waiting in the wings. Their lifelong, selfless practice rooted itself in their fecund, uneasy difference: their queerness. These queer writers and artists took unbreakable vows to their art, dedicating their lives to showing us, their audience, the human condition. Through their art they showed us that the solitude we so fear, that we will do anything to escape, even marry—that solitude is an illusion, a scrim preventing us from seeing how we are all one, we are all in this boat together.

Today, so long as we live in certain states and work for certain employers and have certain incomes and submit to received conventions of dress and gait and accent and beauty, we can assume the mantle of amnesia that is the prerogative of the powerful and prosperous. Now to be LGB (T remains beyond the pale) is no longer to be forced to look outside the norms, since our largely white, entirely prosperous leadership has so enthusiastically embraced the norms. Now we can forget AIDS. Now we can get married. Now we are become the suits.

Years ago, reporting on that ongoing capitalist tragedy called eastern Kentucky, I interviewed Harry LaViers, a Princeton graduate, as it turned out, and among the last of the old-time coal barons, complete with the gold Cadillac and an unmarked office. (He told me that anybody he was interested in talking to knew how to find him.) Capitalism is the best system devised for getting goods and services into the hands of people who want them, he said, then added that it was also extremely cruel. I appreciated his frankness—none of this trickle-down, supply-side folderol. One might think a truly civilized nation could acknowledge and ameliorate the cruelty, and yet since the Reagan years our government has been hell-bent on restoring unfettered capitalism, with its reliance on conquest, extraction, and exploitation, to its late-nineteenth-century shrine.

What can liberate us from this death spiral of consumption we have created for ourselves? When I think of the vanishing species, the filth and pollution we thoughtlessly dump onto Earth and our fellow creatures, the rising desperation evident on all sides, and of us, the rich who have grown fat and sleek by plundering the resources of people in desperate places, hoarding our wealth, building walls, the whole mess of pottage for which we have sold our birthright of clean air, clean water, open space, a clear conscience—when I think of all that, I’m drawn back to the blunt witness of Wojnarowicz:

Each and every gesture carries a reverberation that is meaningful in its diversity . . . we have to find our own forms of gesture and communication. . . . With enough gestures we can deafen the satellites and lift the curtains surrounding the control room.

How is Earth’s situation today different from that of a person with AIDS in 1985? Capital, backed by a growing and ever more heavily armed police force trained to shoot, so thoroughly monitors and controls every expression of resistance that the violent demonstrations of the 1960s come helplessly to mind. Our current political crisis arouses a dark urge to respond to the rhetorical violence of Donald Trump with the literal violence it encourages. Would the Vietnam War have ended without riots on campuses? Would African Americans have made any progress without the burning of cities? Those events, and not World War II, challenge my commitment to nonviolence. Wojnarowicz could be describing our age when he writes,

In a country where an actor becomes the only acceptable president . . . whose vocation is to persuade with words and actions an audience who wants to believe whatever he tells them—in this context, violence presents a truth that can’t be distorted like words and images.

And yet if Pussy Riot can risk years in prison for defending the rights of women and freedom of expression, then my challenge is to rise to the model of their courage. Baldwin, our great twentieth-century prophet, tells us, “Love has never been a popular movement. . . . The world is held together—really it is held together—by the love and passion of a few people.” I take issue with his last point, since every day I encounter people—a lot of people, uncelebrated, unacknowledged—who are making gestures to help one another and heal the planet. Our challenge is to bring their love, reinforced with knowledge, to the forefront: to showcase it as the true desire of the heart, to act out the biological fact that creation and civilization build themselves as much around cooperation as around competition; to teach, in the most emphatic way, our young to be queer, which, as every parent and teacher knows, is through example.

I do not ask that others do as I do, when at a moment’s thought I can name a dozen, a hundred who live with more integrity. I’m saying that those of us who have been given choices have a responsibility to choose the greater challenge, the harder path—the freedom found through wisdom and restraint. We do a little more than we think we are capable of doing, in the place and moment where history has put us.

I write in peony season—extravagant, sweet-scented peonies, reason in and of themselves not for optimism but for hope. Thanks to science, we are the first empire in history to possess the knowledge of what we are doing to ourselves, the causes of our environmental self-destruction—though, as prophets and artists and writers demonstrate, the visionary imagination has no need of data to read the writing on the wall.

We are at an all-hands-on-deck moment in which we demonstrate either that knowledge may lead us to wisdom or that there is no necessary connection. Let us never forget that it was the best and the brightest who engineered the debacle of the Vietnam War. But I take hope in every politician or economist’s statement that Americans aren’t buying enough; in every student’s reference to “sustainability” or “mindfulness,” terms that weren’t in my college vocabulary; in the expansion of the concept and increasing use of queer, founded in a shared resistance to the dominant model, the glorification of greed. I have faith in the capacity of truth, if brought to light and given time, to win its cause; the capacity of love to win its cause.

A lifelong Democrat, I place little hope in conventional politics, so invested are both parties in endless, unsustainable growth, or in conventional religion, with its primary interest being the perpetuation of its power. Instead I find hope in love, for one another, for our Earth. Those of us invested in love can choose, must choose noncooperation. We buy less, we consume less, we take ourselves off the grid despite efforts to force us to remain on it, we politely decline the carrot of state-sanctioned marriage, we dedicate ourselves to friendship as our organizing, bedrock relationship; we study and talk about how to become, in fact, a society of friends. Our quiet, simple lives are invisible sabots tossed into the gears of capitalism.

And yet we want to test ourselves—we need to be tested, even as anyone with a minimal understanding of religion or philosophy understands the impermanence of all material things, especially those created by humans. So we seek our testing in the world of our imaginations; we make commitments; we take vows.

“In regard to marriage, we need more and more complex plots,” wrote Phyllis Rose in her 1983 book Parallel Lives, a wise and thought-provoking treatise on marriage grounded in her investigations into the lives of five prominent Victorian couples. I enlarge Rose’s astute observation to read, “With regard to society, we need more and more complex plots.” I seek models for those plots among the queers—in this specific case, in the caregiving models the LGBT community established in the darkest years of AIDS, before any conception of treatment, before state-sanctioned marriage. I seek communities grounded not in marriage but in friendship, because as partners to every successful marriage know, friendship can survive without marriage, but healthy marriage cannot long endure without friendship.

In my memoir seminar, I asked my students, several of whom were married, which they thought more important: marriage or friendship. Thirteen of fourteen favored friendship, a response I found so incredible that I asked them to keep their hands up while I counted a second time. In their raised hands I find hope—I hear the voice of Walt Whitman’s camerados:

In my memoir seminar, I asked my students, several of whom were married, which they thought more important: marriage or friendship. Thirteen of fourteen favored friendship, a response I found so incredible that I asked them to keep their hands up while I counted a second time. In their raised hands I find hope—I hear the voice of Walt Whitman’s camerados:

As I lay with my head in your lap, Camerado,

The confession I made I resume—what I said to you in the open air I resume:

I know I am restless, and make others so;

I know my words are weapons, full of danger, full of death;

(Indeed I am myself the real soldier;

It is not he, there, with his bayonet, and not the red-striped artilleryman;)

For I confront peace, security, and all the settled laws, to unsettle them;

I am more resolute because all have denied me, than I could ever have been had all accepted me;

I heed not, and have never heeded, either experience, cautions, majorities, nor ridicule;

And the threat of what is call’d hell is little or nothing to me;

And the lure of what is call’d heaven is little or nothing to me;

. . . Dear camerado! I confess I have urged you onward with me, and still urge you, without the least idea what is our destination,

Or whether we shall be victorious, or utterly quell’d and defeated.

“ACT UP was an erotic place,” says one participant in the documentary United in Anger: A History of ACT UP (2012). Another attributes the organization’s success to “that combination of serious politics and joyful living.” I take hope from knowing that, though ACT UP’s anger and tactics were crucial and can provide today’s activists with templates for action, it is the hospice movement, cultivated and refined in the AIDS wards of San Francisco, that has spread.

Some years back, as the author of a book on what it means to have and keep faith, I was invited to the first and last Gay Spirituality Summit, held at the Garrison Institute, on the Hudson River Palisades. The long weekend revealed the rift between those for whom state- and church-sanctioned marriage was a breathtakingly revolutionary goal and the Radical Faeries, who caused an uproar by proposing a “morning masturbation meditation” to clear the testosterone from the air so that the couple of hundred mostly male participants could attend to our business undistracted.

Why does their cheerful pragmatism strike our Gilded Age ears as shocking? What timid times we inhabit! Even in 1915, Wallace Stevens, that insurance executive with New England snowmelt coursing through his veins, could write in “Sunday Morning”:

Supple and turbulent, a ring of men

Shall chant in orgy on a summer morn

Their boisterous devotion to the sun,

Not as a god, but as a god might be,

Naked among them, like a savage source.

On that particular Sunday morning, an impromptu assemblage brought the Radical Faeries and the assimilationists together. We gathered on the bluff facing across the great inland sea of the Hudson to the faux-Gothic turrets and ramparts of West Point. The Faeries invoked cosmic energy, the assimilationist rectors and ministers and rabbis and priests prayed to God or YHWH, but we shared the ideal and hope of projecting loving kindness and peace and harmony to our sisters and brothers across the river, so many of whom—had you not noticed?—share our bent destiny and are drawn to camaraderie, drawn to self-sacrifice, drawn to sisterhood and brotherhood.

Could we not build an Academy of Peace? Could we not increase funding in our public universities for arts and humanities, so as to provide our unemployed and underemployed the means to conceive, create, and sustain beauty? Could we not follow models established in other countries, converting our vacant housing and handsome, emptying monasteries and convents—I live down the road from one—into sustainable communities for the growing numbers who seek to live alone? Could we not take vows of friendship—vows of love?

I feel your skepticism through the page, dear, thoughtful reader, and I stand my ground. Is it not clear that conventional science, conventional economics, conventional politics, and conventional religion are not going to rescue us from ourselves? Can we afford to continue to cultivate and inhabit this age of irony, with our minds separated from our incarnate bodies and the world in which we live? In place of our age of irony, I imagine an age of reverence, chosen in full embrace of the knowledge of science, even as it grounds itself in the calm conviction that we live and die in mystery, that all human endeavor must begin and end in respect, for ourselves, for one another, for our fellow creatures, for our wounded, beloved Earth. Let us all become queers.