On the night of November 27, 2016, Dawinder Singh dropped a bottle of sleeping pills outside his neighbor’s door. He had a soft, cheerful face, a head of woolly curls, and a tendency to laugh at the wrong times. Everyone in Kakheri, his village in the northern Indian state of Haryana, believed him to be gone, perhaps abroad. But here he was, a handkerchief tied over his mouth as if he were a bandit, fleeing to the bus stop.

Inside the house, Neetu Rani, the birdlike beauty he’d grown up adoring, was waiting for her parents to finish their soap opera. Neetu was trim and stylish, and talked about Bollywood actors as though they were her next of kin. When her mother and father went to bed, she went outside to retrieve the pills.

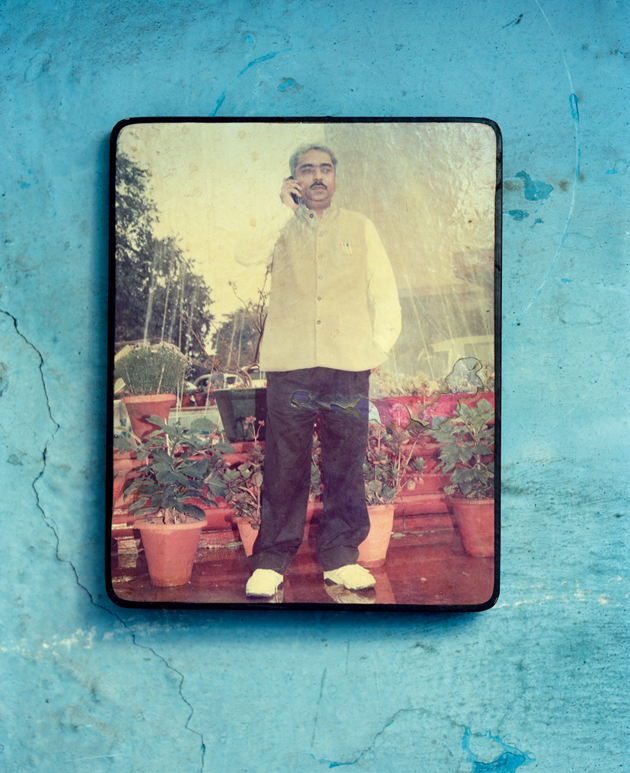

A photograph of Sanjoy Sachdev, the chairman of the Love Commandos. Photographs from New Delhi by Max Pinckers, from his series Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty © Max Pinckers

Two nights later, Dawinder returned in a car with a couple of his cousins, whom he’d recruited by making them watch romantic movies. When they reached Kakheri, they parked on an empty road and waited. At one in the morning, his phone rang. It was Neetu, scolding him in whispers: “What kind of sleeping pills are these?” Her parents had finished bowls of laced beans and rice but were still shuffling around the house. Dawinder asked her to be patient.

After an hour, she called again, reporting that she had shaken her mother, pretending to be scared of the dark, and there had been no response. Dawinder got out of the car and hurried to her house. She had told him not to come barefoot, but knowing that he would anyway, earlier in the day she had cleared the yard of branches and razor-rimmed leaves from the babul tree. Dawinder helped her haul her four suitcases over a low wall, and after the last one, she hoisted herself to the other side. Then they ran: through the narrow lane where they first saw each other, past the cowshed where she used to hide to take his calls, past their school and her father’s firewood shop. Finally, they reached the car.

There was a thick blanket of fog in the air when the cousin behind the wheel began driving. In the back seat, Dawinder slipped a set of twenty-one bangles around Neetu’s wrists: reds and golds stacked between whites and silvers. This was her choora, the marker of a new bride. If she wore it for a year, Dawinder would be guaranteed a long life. He tied a mangalsutra, a thread of small black beads, around her neck, and painted the part in her hair with vermilion. Neetu was now his wife, he announced. She thought that their love story was just like in the movies, only without nice costumes.

As the car sped onto the highway, Neetu began to grasp her new reality. Outside the window, rice fields flew past. She felt herself floating through space. Suddenly her stomach churned, and she realized that she needed to vomit. The car screeched to a halt; she climbed out to throw up. A few miles ahead, she needed to stop again. And again.

Three hours and five episodes of retching later, the cousins dropped the couple at a bus stop in the town of Rajpura, about seventy miles from home. When the bus came, they found seats by the window. Neetu rested her head on Dawinder’s shoulder and described the agony of waiting for her parents to drift off to sleep. “Who knows when they will be able to eat or rest again,” she said.

The sun was rising when the bus rolled through a traffic jam outside New Delhi. Dawinder saw a big, heaving city whose crowds could swallow them up and provide the anonymity they needed to survive. Neetu’s eyes watered from the pollution. Dawinder called his aunt Kulwant, who he suspected would be the only one able to receive the news of his marriage without collapsing. She asked to speak to Neetu. “Don’t betray him now,” Kulwant said. Neetu promised that she would not.

They hailed a rickshaw, which bobbed in and out of potholes and squirmed through waves of pedestrians. Neetu saw a storefront that displayed red, blue, and yellow bras; in her village, she’d been able to buy them only in white. They rode past cheap hotels that offered rooms by the hour, places where married men took their mistresses. Dawinder clutched her hand and told her to trust him.

The rickshaw stopped outside a rusted gate. They looked up at a crumbling building covered in lime plaster, scaffolding, and saris hung to dry. Outside, men were smoking and staring. Dawinder had seen videos of this place, but in person it looked nothing like he had expected. It was too late to turn back now—they had saved up ten thousand rupees ($150) to reserve a space. He took out his cell phone.

“Hello, Love Commandos,” the voice on the line said.

“We have come,” Dawinder said.

“We have been waiting for you.”

In Kakheri, the news of Neetu and Dawinder’s disappearance broke with the sunrise. Neetu’s father—Gulzar Singh, known as Kala—walked around the village, crazed. With his wrestler’s physique and pencil-thin mustache, Kala looked like the villain from the Mahabharata, the Hindu epic in which each character is meant to embody a trait that is supremely good or evil.

Sudesh Rani, Neetu’s mother, sat in her kitchen, sobbing. Friends gathered to commiserate: a runaway daughter was as good as dead. Women in rural Haryana are required to cover their heads and fade into the background in the presence of men; young girls are expected to stay home until they are transferred to a husband through an arranged marriage. Neetu had disgraced her family not only by eloping but by doing so with the short, slow-witted son of a neighbor. According to custom, men and women of the same village are considered to be siblings—the rule serves to maintain a separation of the sexes—which put Neetu and Dawinder’s relationship under the umbrella of incest. Worse, Dawinder was a Sikh, from the Mehra caste of palanquin bearers and boatsmen. His father, Gurmej Singh, was a truck driver turned farmer. Neetu was a Hindu of the Panchal caste, a rank of goldsmiths, stonemasons, and carpenters. Kala, a landlord with a firewood shop, was an important man in the community.

Across the Indian countryside, romantic relationships can easily become ensnared by taboos. Sometimes, the consequences are fatal. In 2007, the bodies of Manoj and Babli, lovers from the same village and the same gohtra—believed to be descendants of a common ancestor—were found in gunnysacks dumped in a canal not far from Kakheri. Babli’s family, which was wealthier, had forced her to drink pesticide; they strangled Manoj to death. With support from leaders in their village, Babli’s parents saw the murders as the only punishment commensurate with their humiliation. This is a common view: according to the latest count released to the public, 251 honor killings occurred in India in 2015.

Neetu and Dawinder’s match should have been unthinkable. When they met, in 2005, her family had just moved up the street. She was nine, he was twelve. After school, Dawinder would play video games with Neetu’s brother, Deepak, and Neetu would play house with Dawinder’s sister, Jasbir. They all got along well for a few years, until one afternoon, when Deepak grabbed Dawinder’s neck during an argument. Kala, who was known to have a short fuse, broke them up and slapped Dawinder, who can still recall the sharp pain of the blow. The families stopped speaking. Besides, the children were entering their teens, and it was not proper for girls and boys their age to spend time together.

A year later, Dawinder noticed Neetu looking at him on the walk home from school. When he got to his house, he made himself a cup of tea and climbed onto a stool in his parents’ room, curious whether he could see her from the window. She was out on her terrace, still watching him from a distance. Feeling bold, he raised his glass to her. She responded by bursting into laughter.

Dawinder was sure that this girl was trying to get him into trouble. But every day after that, Neetu would dawdle on the way home so that the two of them could talk. If no one else was around, they would run into a shed on their block so they could be close. On Karva Chauth, the Hindu festival in which married women fast until sundown for the safety of their husbands, Neetu refrained from eating to show Dawinder that she’d taken him as hers.

Within a year, the relationship was discovered. One night after dinner, assuming that her parents were asleep, Neetu sneaked into Dawinder’s house. The two had hardly a moment together before Sudesh thundered in and dragged her out. She warned Dawinder that if he wanted to live, he should leave Kakheri immediately. Neetu wept all night, begging her mother to believe that she would never see him again. Sudesh cried, too, stopping only to pummel Neetu’s back or pull her hair. Days later, Neetu’s parents carted her off to stay with relatives out of town, and the following spring, they sent her to boarding school.

Dawinder was dispatched to England. His parents sold off their largest piece of ancestral land to pay for his enrollment at a university in London. Upon arriving, however, he found out that they had been scammed; the university had been offering sham degrees and was soon shut down by the government. He eventually got a job as a stock boy at a supermarket run by a Sikh family and was able to send a portion of his salary home every month. But after a year, he was arrested for selling liquor without a license and deported for overstaying his visa. It was too dangerous for him to return to Kakheri, so he went to live with his aunt Kulwant, in another village, and worked at her son’s cell phone shop.

Pinky and Satchin (left) and Bhaskar and Pooja (right), recently married couples at the Love Commandos shelter

Dawinder and Neetu, who had gone on to college, managed to stay in touch. She begged her classmates to let her receive his calls on their cell phones, which they kept hidden behind toilet tanks. The two would discuss mundane subjects—who ate what for lunch, gossip about her brother’s failed love affairs—and assess the profound obstacles facing their relationship. Finally, one evening in 2016, Dawinder told Neetu that this had gone on long enough: they needed to get married. She was twenty and he was twenty-three.

The night that Neetu and Dawinder eloped, his parents were in Ladwa, a town some fifty miles from home, bringing a relative to the hospital. Shortly after their son’s departure was discovered, Gurmej—a short, soft-spoken, fragile man—received a call from a cousin asking to meet him outside the hospital. He found ten men waiting there, wielding bamboo sticks. Kala was sitting on the hood of his car, swaying his head from side to side like a madman, threatening to kill everyone in sight. The men threw Gurmej in the car and drove off.

They brought him to the police station near Kakheri and demanded that the officer on duty compel Gurmej to reveal where the children were hiding. The officer sat them all down, served a round of tea, and explained that he had already been informed about the couple by the Love Commandos, a shelter for people who wanted to marry against the wishes of their families. Neetu and Dawinder were legally adults, who had taken each other as husband and wife. The matter was out of his hands.

When Neetu and Dawinder arrived at the Love Commandos shelter, a dog named Romeo sniffed them for guns and explosives. A young man led them past a double gate and into a three-bedroom apartment. There was a minifridge and a wall shrine of assorted Hindu deities. He brought them to one of the bedrooms, which was cluttered with newspapers, ashtrays, and biscuits. An older man, dressed in a tracksuit, was sitting in a plastic lawn chair in front of a computer. This was Sanjoy Sachdev, the organization’s chairman. He looked unwashed and reeked of cigarettes, but everything he uttered sounded to Neetu and Dawinder like poetry. He told them that even the Hindu deities Shiva and Parvati had married against caste tradition. Neetu and Dawinder felt a rush of confidence.

The Love Commandos operated like a family, Sachdev said, so couples were to call him Baba, or grandfather. (He was a youthful fifty-six.) There were three other commandos, who lived in the building next door and were to be addressed as Papa. Each of them had his particular responsibility: Harsh Malhotra, a former interior decorator and local politician, coordinated rescue operations for couples in distress. Sonu Rangi, a former volunteer for the Hindu-nationalist Shiv Sena party, organized weddings. Govinda Chand, a college student, paid bills and assisted with other work. Sachdev oversaw the registration of marriages.

Before starting the Love Commandos, Sachdev had tried to open a poultry farm, a sweetened-milk company, and a factory for car parts; all those businesses tanked. He worked briefly as a consultant to Indian Railways, entered and lost a local election, and finally became a journalist. But he sensed that he was meant for a larger purpose. One Valentine’s Day, a colleague in the newsroom told him about the Hindu-nationalist groups that roamed parks and college campuses to protest the Western corruption of Indian values. They beat up couples, cut their hair, sprayed them with chili powder, and pronounced them brother and sister. Hearing of the victims suffering for their love, Sachdev thought, “Who were these people to poke their dirty nose in between?”

In 2010, when a court verdict on the Manoj-Babli honor killing was making national headlines, he got the idea to create the Love Commandos. He didn’t like the term “runaways,” so he referred to his clients as “people leaving parental homes for the unification of the love family.” He wanted them to relish their freedom. “This country is sitting on a volcano,” he said. “This is a country of six hundred and fifty million young people. Each young person has a heart that is burning with a flame called love.”

As it turned out, Sachdev had never been in love himself—it was only his work. “I didn’t have time to fall in love,” he said, “because I was busy solving other people’s problems.” When he was twenty-eight, he had an arranged marriage. His wife, whom he described as a dutiful woman, now lived in his hometown, thirty miles from New Delhi, and took care of his father. Sometimes Sachdev would go to see her, but months might pass between visits; planning trips depended on his mood. They had four children, who were grown, and had given him what he described as “an eternal feeling of love.”

Sachdev served Neetu and Dawinder cups of tea and told them the rules of the shelter: no sex, no afternoon naps, and no contact with the outside world. Couples were required to surrender their cell phones so that their location could not be traced. They were also expected to pay for their wedding ceremonies. Neetu and Dawinder were so grateful that, without being asked, they handed over Dawinder’s ATM card and told Sachdev the PIN.

Sachdev thanked them and brought them to their room. It had no windows, and the walls were chipping with pistachio-green paint. On the floor were three tattered mattresses—they would sleep beside the two other couples lodging there. Neetu was surprised; she had assumed that the young man who had escorted them in, and others she’d seen in the kitchen, were domestic help.

Sachdev told them that they had ten minutes to freshen up. Neetu changed into a shalwar kameez, Dawinder threw on a clean shirt. Rangi took them to a nearby building, where, above shops selling spare motorcycle parts and batteries, they stepped into an apartment that had been converted into an Arya Samaj temple. (Arya Samaj, a nineteenth-century movement that supports caste system reform, facilitates intercaste marriage.) As a priest chanted Vedic scriptures, Neetu and Dawinder exchanged garlands and circled a holy fire. A photograph was taken as evidence, and two witnesses, acquaintances of Rangi’s, signed a religious marriage certificate. The last step was to submit the certificate to the government marriage registrar to make their wedding legally binding. Sachdev would take care of that.

Under the authority of the state, love marriages are permitted in India; according to tradition, they are forbidden. In villages across the north, khap panchayats, councils of unelected wealthy elders, resolve local disputes, issue diktats about daily life, and enforce the caste system above the rule of law. Each caste has its own khap to represent its interests.

Following the Manoj-Babli honor killing, a khap leader was convicted of murder. But that ruling was soon overturned, and khaps have continued to facilitate acts of violence, thanks in part to the complicity of politicians who rely on them for votes. “If you say, ‘I’m a Brahman,’ then even the poorest of Brahmans will vote for you,” Ranjana Kumari, the director of the Centre for Social Research, a gender equality group in New Delhi, told me. While India is still debating how much sway khaps should hold in modern society, khap leaders appear on television threatening anyone who crosses them. If nontraditional marriages are socially sanctioned, they argue, the fabric of Indian culture will unravel.

In 2010, women’s rights activists began lobbying for a law to criminalize honor killings, seeking to penalize the full gamut of associated offenses—harassment, intimidation, economic sanctions, social boycotts—that can endanger couples, their families, and anyone harboring them. In their approach, the activists sought to emulate India’s laws against dowry and child marriage, which identify the tradition at the root of the crime.

On their advisement, Kirti Singh, a Supreme Court lawyer in New Delhi, drafted the Prevention of Crimes in the Name of Honor and Tradition, a bill that would hold accountable families that act alone, or with khaps, to punish people who enter love marriages. She also sought to end collusion between vengeful families and the police. “The police don’t act for the couple,” Singh told me. “Instead, they act for the girl’s family. Because they themselves come, I suppose, from a society and a way of thinking that believes there shouldn’t be choice marriages, particularly in cases where it’s an intercaste marriage.” The bill stipulated that if a couple tells a public servant that they want to be together, the police cannot process a family’s complaint against them. That would counter a common tactic in which families file false cases of kidnapping and rape against the groom.

Singh delivered her draft legislation to the Law Commission of India, an executive body tasked with legal reform. Two years later, however, the commission released its own version of the bill, Prevention of Interference with the Freedom of Matrimonial Alliance. The revision maintained that khap intervention in marriage should be criminalized, but it did not account for the roles of families and police officials. For that bill to become law, it would require input from representatives of every state and union territory, along with approval by three national ministries, before it could be presented to a standing committee, which would then consider it for parliamentary debate. Yet today, five years later, the proposed legislation has not been cleared by the ministries. “This bill will never be a priority for the government,” Ravi Kant, another Supreme Court lawyer, told me. “The government doesn’t want to put its hand somewhere it can get stuck.”

One afternoon, Jagmati Sangwan, an activist with the All India Democratic Women’s Association, a feminist group, took me to a government safe house for couples at an abandoned school in Rohtak, a town in Haryana. Her organization had scored a rare victory for runaways when it successfully lobbied the Punjab and Haryana High Court to establish the safe houses, in 2010. But few people were coming, Sangwan told me, because they feared that police would turn on them.

When I visited, four couples were asleep on the floor of a classroom. The walls had been carved with lovers’ names. Only runaways who have been granted protection by a legal order are permitted to stay there; one pair told me that they had stolen gold from their parents to hire a lawyer to petition the court for their admission. The order comes with an expiration date, however, and after a couple leaves the safe house, they are likely to go on being harassed by their families.

The Love Commandos, on the other hand, advertises a one-time fee that covers the cost of a wedding ceremony and registration; couples are invited to stay as long as they need. Perhaps more important is Sachdev’s promise to protect them even when it compromises his safety. Armed men and disgraced relatives routinely come knocking, he said, and at least four khaps have issued bounties for his death. None have made good on their promise, but he and his colleagues have been beaten. “Look, we are madmen,” he explained. “We are not scared of dying.”

In January 2017, I visited Neetu and Dawinder at the shelter. Neetu told me that all her dreams had been coming true: first, they got married in a big city; then, on New Year’s Eve, they slow-danced. She sat on the floor in Sachdev’s room and read from her diary, in which she noted the important events in her life—the first time she and Dawinder kissed, the morning they showered together, the night they spoke on the phone for almost eight hours. Sachdev was sitting nearby, drinking a glass of water and trying to keep a straight face, but finally he started laughing so hard that he spat out of his mouth.

“What did you talk about for so long?” he asked.

“I keep telling her, Baba, ‘How much will you talk?’?” Dawinder said. His face crumpled with embarrassment.

“If I had to talk to someone for thirty minutes, I would go mad,” Sachdev replied. “After two hours, I would be inside a coffin.”

Neetu and Dawinder had been in the shelter for several weeks, but Sachdev still had not taken their paperwork to the registrar. Whenever they asked, he assured them that he would get to it as soon as he could. Sometimes he would say there was too much traffic or that he was feeling ill. In the meantime, he would ask them for money to help cover the cost of his hospitality. As days progressed, according to Dawinder, they paid Sachdev fifty thousand rupees ($775) in unidentified general fees. Neetu would remind him that marriage registration cost only a few thousand rupees; Sachdev would look hurt and say that he had treated them like his own children, but now she was bringing money between them.

While they waited, Dawinder and the other young men at the shelter were expected to run errands for Harsh Malhotra, the chief coordinator, a hulking man with a short temper. Whenever he rang a bell, they were to gather on the balcony to receive instructions. He’d have them go out to buy him a pack of cigarettes and a bottle of whiskey, play cricket with his nephew, mop, sweep, or walk Romeo. The women stayed inside to clean and cook.

Prospective donors, many of them from the West, routinely came to visit. The biggest contributors were an online matchmaking service and Björn Borg, a Swedish clothing company. In his pitch, Sachdev would describe his lofty ideas about freedom and choice and ask the runaways to talk about how he had saved their lives. He would tell guests that he was protecting hundreds of couples in a network of eight shelters across the country, but he never divulged any details, saying that would compromise their safety. Within a year, Sachdev would say, he planned to expand the Love Commandos into Pakistan and Bangladesh. Recently, he’d started a campaign on a crowd-funding site to grow his visibility online.

His associates had sold their apartments, cars, and gold for the cause, Sachdev said. He had taken money from his children’s salaries and his father’s pension. He’d also solicited donations from a marriage registrar: “Whenever I see him, I pick his pocket,” he told me. Yet the Love Commandos was not registered as a charity, nor did it pay the taxes required of a business; all donations went into Sachdev and the other commandos’ private accounts. He told me that donors never asked questions about how their money would be used, and that most contributions were made in cash, which made accounting for them difficult.

When I asked Sachdev for a breakdown of his finances, he said that his organization needed at least ten lakh rupees ($15,000) every month to keep the shelters running. But the numbers he provided didn’t add up. For the shelter in New Delhi, he paid twenty-six thousand rupees ($400) in monthly rent. He also had to cover the electricity, water, and grocery bills for the fifteen or so people who lived there at any given time. He told me to multiply that by eight for the secret shelters—but he still refused to show me where they were, or to introduce me to any couples who had stayed at them.

Sometimes marriages needed to be registered in tatkal (“at short notice”), Sachdev went on, which required a government fee of another ten thousand rupees ($150). There were couples who could not afford their own wedding ceremonies, so that meant ghee, sandalwood, the priest’s tip, garlands, and sweets. Certain couples needed to be rescued, and that required cars, walkie-talkies, and emergency funds. Photocopying and notarizing documents cost money. And even though the Love Commandos operated within the law, Sachdev said, gifts had to be sent during the festivals of Diwali and Holi to “speed up” officials he relied on for help. He told me that bribes were paid “in friendship” and added, “When you work for the right cause, you realize that policemen and crooks are also human.”

Ravi Kant, the Supreme Court lawyer, told me that he was suspicious. The optics of defying caste and uniting lovers made a good business model, especially if it was aimed at liberal-minded donors. “If a body is not registered, then we can say that it is running illegally,” he said. “This might be a case of someone getting a sense that by giving protection to couples you can make money.”

One afternoon, Sachdev coordinated a rescue mission from his bed. The daughter of a government official in Bareilly, a town in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, had been kidnapped by her relatives while returning home from work in New Delhi, where she lived with her husband, who was from a lower caste. Sachdev, horizontal and smoking a cigarette, tweeted at the state’s chief minister, and by the next morning, the couple was at the shelter. Immediately, he inspected their papers, which included a religious certificate but not a court-issued license, and started their legal registration.

Later that day, Dawinder shouted at Neetu for eating sweets that the newcomers had brought. She was so angry that she removed her choora, throwing the bangles to the ground. “Dav said that he will drop me to my house tomorrow,” she wrote in her diary that night. “I forgave him for the twenty-fifth time. Now I have to stop keeping count.” Moonlight poured into the bedroom from the street through a vent. Everyone appeared to be asleep, but then Neetu noticed a couple rocking under a mountain of quilts. She knew how elusive privacy was at the shelter, but she could not keep herself from laughing. Dawinder, rousing at the sound of her voice, looked up, and soon he sank his head into the pillow, laughing, too.

The extended stay in such tight quarters had been wearing on them. After two months, they bickered over small things, and grew anxious about what was holding up their registration. The Bareilly couple had been taken care of right away, but those without government connections seemed to be stranded in limbo.

Afsana and Malkit, a couple with whom Neetu and Dawinder had become friends, eventually declared that they were tired of Sachdev’s excuses, and left. Soon, another pair took off, fuming. Dawinder wanted to follow them out, but when he and Neetu discussed it, he would cry, “We are poor, no one is listening to us, we are runaways. What will we do?” He was afraid that Sachdev might refuse to hand over their marriage documents, as he had done to others. Without valid IDs, registration might never be possible, and they would risk being separated. Dawinder wondered whether they had left one oppressive system for another.

By the end of January, they decided that they’d waited long enough. Whenever Sachdev stepped out of his room, Dawinder secretly scanned their paperwork as Neetu kept watch. Sneaking around made them both nervous, and they continued to snap at each other. Dawinder would tell Neetu of the Love Commandos, “Before getting us married, they will get us divorced.”

One day, Dawinder went downstairs to walk Romeo and made a surreptitious call to the cousin who had driven the getaway car. The cousin told him that, back in Kakheri, his parents’ lives had been upended. They were shuttling from one relative’s home to another, fearing violence from Neetu’s family. Hearing this, Dawinder wanted to leave the shelter that very afternoon. Neetu agreed.

When they approached Sachdev, he refused to provide them with the log-in information they would need to book an appointment for court registration. If they left, he said, he would call Neetu’s family and they would be killed. “But we did not get scared,” Neetu wrote in her diary.

At the door, the commandos inspected their bags. Dawinder asked for their cell phones—there were three, which he’d brought from his cousin’s shop. Sachdev returned only two. “Go, run,” he told them. “You’re not getting this one.” Neetu grabbed the last phone from his hand and slammed the door behind them.

Neetu and Dawinder went to stay with Afsana and Malkit at Malkit’s family’s apartment in the city. By some miracle, their parents had grown tired of the hostility and decided to support their relationship.

A few days later, Dawinder’s parents arrived. Gurmej had brought his savings in a plastic bag; he was now willing to pay for his son’s marriage license. At a lawyer’s office, he explained that they were poor and desperate. After some negotiation over her fee, she took them to a temple, where Neetu and Dawinder were married yet again. They were registered by the court that afternoon. The lawyer took ten thousand rupees ($150), less than a fifth of the amount that Neetu and Dawinder had paid the Love Commandos.

In the evening, the family went to a gurdwara, a Sikh temple, where they would spend the night. Gurmej carried Neetu’s bags. Sukhwinder Kaur, Dawinder’s mother, doted on her, kissing her palms and calling her daughter. The next evening, Neetu and Dawinder left for Aunt Kulwant’s; they figured that only harm awaited them in Kakheri. Dawinder’s parents went home, with the intention of selling their house. Someday, they told one another, they would all go far away and live together in peace.

A little more than a month later, on March 20, Neetu and Dawinder were sitting down for dinner when the phone rang. His parents had returned home from visiting a relative and found the place in ruins. The doors had been busted open, the jambool tree in the courtyard was slashed, trunks full of clothes and valuables were empty, and an entire wall was missing. Neighbors gathered outside to survey the damage. Gurmej sensed that something worse was about to happen, so he jumped on his motorcycle and rode to the police station.

In the two hours he was gone, Neetu’s family came back. Kala had an axe, his brothers had knives and bamboo sticks, Sudesh was carrying a sickle, and Ruksana, Neetu’s younger sister, wielded an iron rod. Sukhwinder hid in her son’s room, but Kala and his brothers dragged her out by her hair. They took her to the center of town, where they kicked and beat her until she vomited. Spectators huddled around. “Kala told me, ‘We will make you drink our piss,’?” Sukhwinder recalled. Eventually she passed out, her face in the dirt. Kala and the family kept at it until someone in the crowd suggested that she might already be dead.

Gurmej spent the next few weeks trying to get the police to take action, but it became clear to him that for a poor man in India, justice was elusive, especially if your son eloped with a woman in violation of tradition. He spent days in the waiting rooms of police stations, begging officials. His own son had created this mess, they told him. Only after he obtained a medical report detailing Sukhwinder’s injuries were charges filed. But a month passed, and the police did nothing.

In April, Gurmej went to the High Court of Punjab and Haryana, in Chandigarh. He arrived at dawn, after taking three buses overnight, and waited under a tree until the court opened. For a fee, a stenographer typed up his grievance letters to police officials and the chief minister; Gurmej received no response. Kala and his family continued to roam the village freely. Gurmej and Sukhwinder, too afraid to return home, lived out in a shed in their fields.

One afternoon, Dawinder and Neetu joined his family to visit the offices of Muhammad Akil, the state chief of police in Haryana. In the waiting room, Neetu rose to get a drink of water, and she was summoned by the officer’s secretary. The secretary told her that she had read her petition. She asked Neetu why she had eloped and ruined so many lives. “Parents always have the best interests of their children in mind,” she told her. Neetu nodded, holding back tears. She couldn’t think of anything to say that would convince this person that her choices were justified.

The family expected to leave with nothing; appealing to the police chief was a shot in the dark. If low-ranking officers did not have patience for them, why would Akil bother? But to their surprise, he directed his officers to arrest Kala and his brothers. Dawinder’s parents were given police escorts.

The next day, Gurmej headed into town along with two policemen. On his way, he passed Sudesh. She stared him down and said that Kala would be back for revenge: his family would be killed even if they were hiding in hell. Satish Kumar, one of the police escorts, told me that he advised her to shut up and leave. He did not arrest her, because the warrant against her family did not include women.

After two weeks, the policemen assigned to accompany Dawinder’s parents stopped coming to work. Kala and his brothers were released on bail. Gurmej couldn’t sell his house—no one wanted to inherit the site of a community feud.

One morning in the spring, Neetu was sitting on her bed, in a pajama set, looking like she had seen a ghost. She had awakened from a nightmare in which she saw herself at Dawinder’s feet, begging him not to leave her and return to his parents. She kept telling him that she would die without him, and then he walked away.

It was only a dream. But living with Kulwant, Neetu had become miserable. In the absence of Dawinder’s mother, Kulwant had taken it upon herself to make Neetu a good daughter-in-law. She demanded to be called Mummy and forbade Neetu to use a cell phone or step outside without her head covered. At mealtimes, Neetu was required to eat after the men. If Dawinder and Neetu went up to talk after dinner, Kulwant would press her ear against their door to listen. A girl like Neetu could not be trusted, Kulwant told me, since she had not been loyal to her own parents.

Not long after they’d moved in, Neetu discovered that she was pregnant. The celebrations were eclipsed, however, by fallout from the attack on her mother-in-law. “Love = Destroy life of many people who belong to you,” Dawinder texted me one evening. Later, another message came in: “What is the point of any of this?”

Despite the joyous news, Dawinder seemed dour. If Neetu took too long to bring him food, he would scream. When Kulwant lashed out at her for sleeping in, he stayed silent. One day, she stepped outside in a sleeveless top, and he tore it in a fit of rage, saying it was inappropriate. The romantic songs that Neetu once adored now sounded absurd; she asked him to play one for her, and an argument erupted. “I started crying in the room upstairs,” she wrote in her diary. “I felt as if there is no one in this world that is mine.” The same man who only months earlier had performed sit-ups in a room full of people at the shelter just to make her smile could no longer understand her.

Dawinder was overwhelmed with guilt. He got a job delivering mobile minutes cards to shops around town; when I accompanied him on his route, he told me that he harbored doubts about what his relationship was worth. His parents were still being tormented, and Neetu was still unhappy. What good had marriage brought?

During one of my visits, the family gathered in the living room, and the conversation veered to Neetu and Dawinder, as if they were not present. Kulwant’s husband said that eloping had been too costly for Dawinder. “Everything is over,” he said.

“He is a good boy,” Kulwant replied. “He would never have done this. But she would call and keep calling. She is the root of all our problems—this girl.”

“Now that they are married, ask them, what is their situation?” Kulwant’s husband asked. “Are they happy now that everyone is destroyed?”

“I have seen how sad he is. He goes in the room and cries and cries. Her parents are fine. She has got only joy from this—I just hope that one day her father is run over.”

Neetu cleared her throat and turned to me in disbelief. “They are saying that they hope my father dies in an accident,” she said.

The next day, Neetu slept until noon, and in the hours that followed she hardly moved. It may have been pains from the pregnancy, or something else—she wasn’t sure. Dawinder took the day off to care for her. Downstairs, he read the newspaper: anti-romeo squads accused of harassing couples. At each word, he sighed. In recent weeks, vigilantes had resurfaced across northern India, barging into bedrooms to beat up lovers. “Look,” he said. “This is what happens to people like us.”

Neetu finally got out of bed and went to the kitchen. Dawinder fed her a bowl of kheer, a rice pudding. At the table, she put her head on his shoulder, he put his arm around her, and they called Sachdev. They had been in touch with him since they left the shelter, seeking help on Sukhwinder’s case from his contacts in the Haryana state police and the government; each time, he had refused to assist without an advance in his bank account. “Baba understands only the language of money,” was Dawinder’s judgment.

Yet they had become nostalgic about the Love Commandos—about their simplifying retreat from the aggression at home, and about the time when their life together was still a happy possibility. The phone rang. “Have any new couples come?” they wanted to know. Neetu had taken to calling their stay at the shelter a honeymoon.