The year 2017 was, I presume, an awkward, anxious moment to be named poet laureate of the United States. What the writer owes the collective and where she fits within it is a fraught question at the best of times, one subject to frequent border disputes. Yet Wade in the Water (Graywolf Press, $24), Tracy K. Smith’s first collection since her appointment, considers the state of the union with characteristic grace.

Pomegranates, by Dana Zaltzman © The artist. Courtesy Zemack Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Smith begins at home. The opening poem, “Garden of Eden,” offers a portrait of the artist resting uneasy amid her upper-middle-class comforts. We are to see America and the world through the eyes of someone who goes to therapy and shops for high-end groceries:

It was Brooklyn. My thirties.

Everyone I knew was living

The same desolate luxury,

Each ashamed of the same things:

Innocence and privacy.

With that established, the book begins to crack itself open, letting in what innocence and privacy might allow you to keep out, as Smith’s more autobiographical poems make room for other voices. There’s an edit of the Declaration of Independence that ends,

We have reminded them of the circumstances

of our emigration

and settlement here.

—taken Captive

on the high Seas

to bear—

There are poems constructed from letters by slaveholders and by African Americans fighting in the Civil War (“I will be hom next fall / if I live a soldier stand a bad chanc but if god spars me / I will be home”), and one that juxtaposes accounts of Muslim-American women attacked in the wake of the presidential election with oddly poetry-ready words published on the Daily Stormer, a neo-Nazi website (“We want these people / To feel that everything around them is / Against them. . . . And we want them to be afraid”). Smith holds this chorus together quite beautifully, often embedding contrasting fragments of text and tone in classical forms and schemes.

Shame lingers, but often on a larger scale: Smith imagines the creatures and oceans and “epochs of rock” trembling when God creates man and, at the end of the book, pictures a bizarre postapocalyptic reprieve, in which long-vanished fauna return and “we wept to be reminded of such color”; she feels “ashamed, finally” of our own flashy creations, all the roads and “bridges slung with steel / Our vivid glass, our tantalizing lights.”

Abyssal Zone

Fauna and Flora, c. 1900, from the Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, published by Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig, Germany

Smith seems to want to show a country to itself, and a people — not just an American people, either. This can yield false notes (I could have done without the penis and rape metaphors in “A Man’s World” and “The World Is Your Beautiful Younger Sister,” respectively), but for the most part she is too attentive to overgeneralize. Some of the most striking poems here are the simplest, such as the incantatory “Ash,” which strips the human being to what it shares with other creatures and objects and places, as a “house that believes it is not a house”:

House of trick and suck and shrug.

Give-it-to-me house. I-need-you-baby house.

House whose rooms are pooled with blood.

House with hands. House of guilt. House

That other houses built. House of lies

And pride and bone. House afraid to be alone.

Poetry is built for deftness — to imply what it leaves out and to reveal what has been left out elsewhere. (Smith’s “Declaration” and other “erasure poems” are literal examples.) Perhaps that’s why a poet can wear the national mantle more lightly than a novelist. The Australian writer Gerald Murnane, though much admired outside his country, is notorious for never having left it, and in Border Districts (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $23), he considers place and the divide between minds, between individual and collective, by traveling inward. Slender, tricksy, and absorbing, this new book announces itself “A Fiction” on the cover but, inside, protests the label at every opportunity.

The aged narrator has moved from the capital of his state to a remote border town in order to gather his thoughts. The entire action of the book consists of a mind reconnoitering its own territories according to a rigorous system of its own devising. (Though he mentions a wife and grown children, we hear almost nothing about them, or about his real-life interactions with anyone else; other people are constantly upstaged by color and light.) The object of study is what Murnane’s narrator calls “the actual,” which is not what it sounds like but rather “the seeming-scenery behind everything I did or thought or read.” Having lost his Christian faith quite suddenly in his youth while reading Thomas Hardy, just as his elders had warned would happen if he read indiscriminately (Murnane, in his unfailingly serious way, is very funny), the narrator retains a fascination with what exactly believers see in their minds while praying, and what happens to these images once belief is abandoned. One of his great and recurring disappointments is the failure of the former faithful to spill the beans on any of these crucial questions. A lapsed priest provokes special irritation when he becomes a writer and insists instead on making strained comedy out of such matters as masturbating while ordained or emptying one’s bursting bladder into a bottle of Seven Hills altar wine.

Ned Kelly, by Sidney Nolan. Courtesy private collection © Agnew’s, London/Bridgeman Images

Murnane’s narrator dedicates himself to a cracking-open not wholly unlike the one Smith offers, except he believes that only by staying still and paying close attention to the inner landscape can one learn anything worthwhile. The political problem of “innocence and privacy,” of allowing oneself to be comfortably shut off from other lives and places, does not arise. In what may be the most poignant account of mansplaining ever given from the other side, he recalls unleashing his thoughts on an early girlfriend en route to a picnic, unable to stop talking even though he was aware that he had lost her interest entirely and for good. As he blurted on, he sensed that the book he hoped to write “was less likely to be written by a man with an ideal female confidant than by the solitary man that I was soon to become.”

Much time is devoted to an experience he had decades ago of observing a patch of stained glass while alone on the veranda at a wedding reception. Citing Kafka in his customary inexact fashion (since books, while often more vivid than everyday experience, get much of their significance from the imaginative digressions they allow the reader), he writes:

Keep to your room for long enough, and the world will find its way to you and will writhe on the floor in front of you — this was my remembered version of the quotation, and I got from it on that afternoon the promise that I need only pass in my mind through some or another doorway framed by coloured panes and to wait on some or another shaded veranda in my mind until I should have sight of the finish of race after famous race in the mind of man after man in one after another mostly level district of what I would recognize, late in life, as the setting of the only mythology of value to me.

Long, liquid sentences seem apt to induce a trance even as they keep drawing the reader’s attention back to the only immediate reality, which is that we are reading Murnane’s words. His account of distraction, the mind’s constant wanderings while reading and writing, creates a mise en abyme in which we read and think about him ruminating on his reading and thinking about reading and thinking until the book rather gloriously threatens to swallow itself whole.

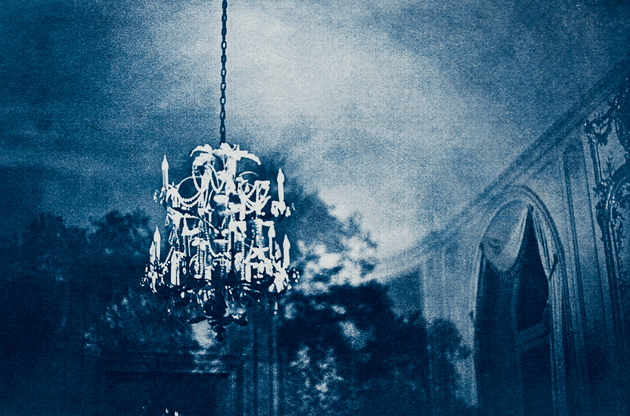

All this looks very tranquil next to the work of Clarice Lispector, who likewise prioritizes the spiritual and mental journey above anything more quotidian — or, rather, continually finds the former in the latter. In her second novel, The Chandelier (New Directions, $26.95), from 1946 and now appearing for the first time in English, you can find writhings galore.

For its heroine, Virginia, living is a precarious business:

Atop each day she’d balance on the tips of her toes, atop each fragile day that from one instant to the next could snap and fall into darkness. But she miraculously would cross it and exhausted from joy and fatigue reach sleep in order on the next day to begin again surprised.

This drama takes place in a physical landscape far vaguer than Murnane’s, as Virginia moves back and forth from the family home, Quiet Farm, in Upper Marsh, to “the city” and all it implies.

“Chandelier,” by Danielle Voirin © The artist

Since Lispector’s surge into high intellectual fashion in the United States a few years ago, she has been narrowly but passionately adored in part for the chaotic inwardness of her narratives and the rough music of her language, whose oddities are affectionately preserved or at least gestured at in all the newer translations. Pathetic fallacy reaches new heights as Virginia takes a shower, “the jet of blind and excessively happy water frightening the silence,” skips past the titular chandelier as it “would scatter in chrysanthemums and joy,” or looks out the window to see that the “enraptured and weak morning was radiating outward like a bit of news.” Meanwhile, her sister’s body is “exacerbated like a lemon,” and in the course of a page or two, Virginia’s “cold cheek sharpened in brightness” is also “sweet like that of an animal eating from your hand,” and then it “awoke like an anthill in the sun.”

Early on, Virginia’s cherished and rather sinister brother, Daniel, upbraids her for her pusillanimous conventionalism: “Every day when you see milk and coffee you like milk and coffee. When you see Father you respect Father. When you scrape your leg you feel pain in your leg, do you see what I’m saying?” He insists that she “figure out what is your own and what is stuff you’ve been taught.” The reader, privy to what goes on in her head, could be forgiven for suspecting that thoughtless adherence to convention isn’t exactly Virginia’s problem. Still, it’s true that the frequent glimpses of what is happening to her on the outside — at home, on the street, at dinner parties, at an inconsiderate boyfriend’s place — suggest the kind of dispiritingly ordinary life that no one would wish on a sensitive person. Pulsing descriptions of her inner struggles make up the bulk of the novel, driving it forward in an ever-recurring epiphanic rise and fall.

As children, Virginia and Daniel play in a clearing “where everything that had to happen in somebody’s life hurried up and happened,” and that’s a good hint at how the novel is structured, as a forested tangle of terrors and extremes where the usual elements of plot — domestic violence, secrets revealed, humiliations endured, arguments, unsatisfactory affairs, a hit-and-run — have to squeeze themselves into the clearings in between, a paragraph or two at a time.

For my money, Lispector could have left even more out. The Chandelier doesn’t measure up to the likes of The Passion According to G. H. (her famous showdown between woman and roach). That novel’s intensity is more ruthlessly controlled, and its reaches must confront race, class, shame, God, humanity, and nature while locked for the book’s span in a single mind, in a single room. Lispector’s approach, like Murnane’s, trumpets its self-sufficiency such that the reader might occasionally wonder what he or she is doing here, but in fact these fictions work just as others do, by arranging words to produce a reaction, an effect. You could say that Lispector’s method involves neither showing nor telling but provoking. That may be as good an answer as any to the question of what a writer owes her public.