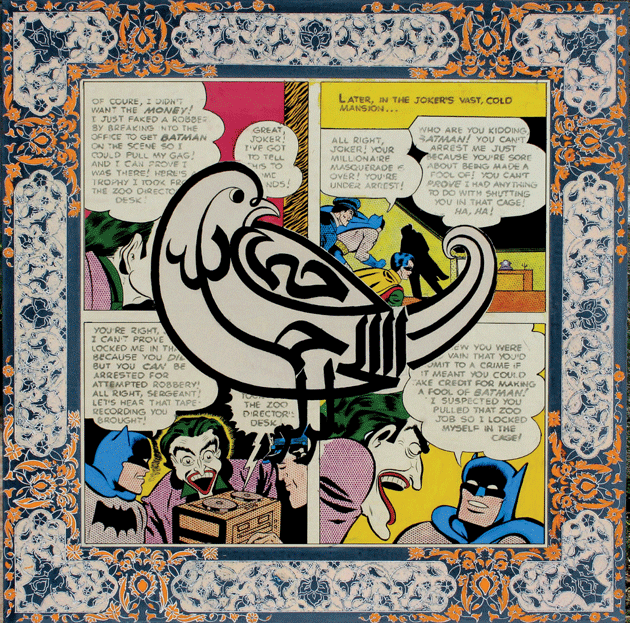

Before he died, my father reminded me that when I was four and he asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I said I wanted to be a writer. Of course, what I meant by “writer” then was a writer of Superman comics. In part I was infatuated with the practically invulnerable Man of Steel, his blue eyes and his spit curl. I wanted both to be him and to marry him—to be his Robin, so to speak. But more importantly, I wanted to write his story, the adventures of the man who fought for truth, justice, and the American Way—if only I could figure out what the fuck the American Way was.

How could I tell the story with such glaring holes in my knowledge? I was terribly bothered that I did not know what the American Way was, and became even more so when I began to wonder whether there was such a thing as the Lebanese Way and whether I would recognize it. My parents were Lebanese, but I was born in Jordan, raised in Kuwait. Could my way be Kuwaiti and not Lebanese? Since most of my classmates were Palestinians, I had a Ramallah accent. Did that mean I’d lost my way?

I wanted to tell stories that belonged to me. Superman would be my friend, his world mine. In a single bound, he would leap the tallest buildings, basically my house and my cousins’ across the street. My Superman would be more powerful than a locomotive, stronger than my father’s red Rambler. I wished to share my story with the world, and it did not occur to me at that age to ask whether the world had any interest.

Who gets to tell stories? Let me answer this quickly: for the most part—and the exceptions are relatively recent—the writers who are allowed to talk are those who prop up the dominant culture, who reflect it with a gilded mirror. But wait: writers have been critical of the dominant culture for quite a while, you may say. Look at James Baldwin, look at Margaret Atwood and The Handmaid’s Tale. Well, fine, but criticism of the culture is not necessarily a threat to it. When the story is truly threatening, the writer is marginalized, either deemed a “political” writer or put in a box to be safely celebrated as some sort of “minority” writer. In his day Baldwin was considered more a black writer than a writer, and so he still is. If he is inching his way into the canon, it is because the culture has shifted. Overt racism is a bad thing now, so a liberal American can read Another Country and think, sure, there were a few bad apples back then, but this is not about me or how I live. It is easier now to tell ourselves that Baldwin is not talking about us, that he is criticizing people we no longer are.

When I bring this up in conversation, people stop me in my tracks because, you know, Conrad, Heart of Darkness and all that. Didn’t he criticize empire?

He didn’t. A story about a bickering couple does not threaten the institution of marriage. Heart of Darkness might disapprove of colonialism, but it’s not an attack on empire itself. The book deals in strict dualities and reinforces the superiority of Western culture and ideas. Africa, its jungle, is what blackens Kurtz’s heart, and just in case you start to feel uncomfortable because you find yourself identifying with him, the supposed bad apple—the Lynndie England of nineteenth-century Europe—Marlow, the novel’s cordon sanitaire, is there to make you feel better. If that’s not enough, it’s actually some other shadowy narrator telling you what he heard when listening to Marlow’s story, so you, imperial citizen, are at least two steps removed from the apple and its African rot. No need for you to feel yourself in jeopardy. Your world might not be perfect, but that other world, that world of the other, is just simply horrid.

In Chinua Achebe’s 1977 essay on Heart of Darkness, he accuses Conrad of “thoroughgoing” racism and adds:

That this simple truth is glossed over in criticisms of his work is due to the fact that white racism against Africa is such a normal way of thinking that its manifestations go completely unremarked.

In other words, Conrad not only shares the dominant point of view but makes it stronger. He might prick it with a pin every now and then, but he is by no means threatening the culture. In fact, he is glorifying it. Achebe uses a phrase that I will return to: Conrad is a purveyor of comforting myths.

Where I disagree with Achebe is that, because of the racism in Heart of Darkness, he refuses to consider it a masterwork. Like all books, Conrad’s novel is limited by his vision, his biases, his worldview. There is no writer with limitless vision, no writer whose worldview is shared by everyone. The problem is not that people read Heart of Darkness as a masterpiece—it is one—it’s that few read books unsanctioned by empire, and even if you wanted to, there aren’t that many available. Today’s imperial censorship is usually masked as the publisher’s bottom line. “This won’t sell” is the widest moat in the castle’s defenses.

Heart of Darkness echoes everywhere today. Take the American war novels about Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq. They are often considered critical of war, hence you might think of them as dangerous to the institution of war. But most of them deal with the suffering of the American soldiers, the Marines who were forced to massacre a village, the pilots who dropped barrel bombs and came home suffering from PTSD. If anything, this is helpful to the cannibalistic war machine. Such war novels make us feel bad and at the same time allow us to see ourselves as the good guys. We are not all terrible, for we suffer, too.

In one of the most gorgeous passages at the end of Heart of Darkness, Conrad describes at length the suffering of a mass murderer’s widow, though he glossed over that of the murderer’s victims. Conrad did not create the original mold for this kind of writing—from Homer to Shakespeare to Kipling, everyone has done it—but he became the standard because he was so good. We invade your countries, destroy your economies, demolish your infrastructures, murder hundreds of thousands of your citizens, and a decade or so later we write beautifully restrained novels about how killing you made us cry.

Among the many writers who have responded to Heart of Darkness, my favorite is Tayeb Salih in Season of Migration to the North. This short novel, published in Arabic in 1966 (the first English translation came out in 1969), refers to a number of classic works of Western literature—Othello, The Tempest—but primarily it engages with Conrad. Where Conrad wrote of colonialism as a misadventure that forced enlightened man to encounter his opposite in the heart of darkness that is Africa, Salih, who is Sudanese, calls the entire enterprise of empire a “deadly disease” that began “a thousand years ago,” a contagion that began with the earliest contact, the Crusades. Conrad’s Kurtz is mirrored in Salih’s Mustapha Saeed, who leaves his small Sudanese village and moves to his heart of darkness, London. Once enmeshed in the city’s web, Saeed decides he will “liberate Africa with his penis.” Like Kurtz’s time in Africa, Saeed’s stay in London results in a trail of dead bodies—his lovers who commit suicide, the wife he murders.

Salih’s novel simultaneously emphasizes and breaks down the dualities between self and other, between white and black. Saeed is shown as both the other and the double of the unnamed narrator, a man from the same village. The line demarcating the dualities is not clear-cut. Compared with Heart of Darkness, Season of Migration to the North is a study in subtlety. Whereas the denizens of Conrad’s Africa are “just limbs or rolling eyes” who grunt and snort or are cannibals who want to “eat ’im,” Salih’s Africans think, act, and speak—an amazing concept. And Salih is more generous than Conrad: he allows the denizens of his heart of darkness to be human as well. Even these imperial interlopers are allowed to talk, if only to act on ridiculously sexist and racist sentiments, as with a woman who says to Saeed, “Ravish me, you African demon. Burn me in the fire of your temple, you black god. Let me twist and turn in your wild and impassioned rites.” (There are prejudices and there are prejudices, of course, and suffering under someone else’s does not inoculate you from subjecting others to your own. In Salih’s book, in other words, sexism “is such a normal way of thinking that its manifestations go completely unremarked.”)

The gravitas in Salih’s novel is in the return home. Conrad’s Kurtz dies, Marlow returns to England a tad traumatized. In Season of Migration, both Saeed and the narrator return to Sudan after a stint in London, and they find that they no longer fit where they belong. The narrator says:

By the standards of the European industrial world, we are poor peasants, but when I embrace my grandfather I experience a sense of richness as though I am a note in the heartbeats of the very universe.

Neither man can be that note any longer; neither can recover the experience of being part of the village. They are caught in countercurrents.

The novel ends with the narrator in the river, not the Thames or the Congo but the Nile, struggling to stay afloat:

Turning to left and right, I found I was halfway between north and south. I was unable to continue, unable to return.?.?.?. Like a comic actor shouting on a stage, I screamed with all my remaining strength, “Help! Help!”

Think “The horror! The horror!”

Colonialism dislocates you in your own home.

I don’t have to tell you that Tayeb Salih is not widely read in our dominant culture; or, to put it in the terms I’m using, he isn’t allowed to talk here. He isn’t a purveyor of our comforting myths. He is, however, read among Arabs, at least among the intelligentsia. The book was published to great acclaim and is now recognized as one of the masterpieces of Arabic literature. So: Is Salih the purveyor of comforting myths in that world? His novel might not subscribe to the American Way or the Colonialist Way, but does it subscribe to the Arab or the African Way? One has to wonder if it fits into a dominant Arab culture that blames all its ills on colonialism.

The question is important for me, so let me take it a little further: even though Salih wrote the book in Arabic, he was still a Western-educated man who spent most of his life in London. To the Sudanese, he may be closer than an Englishman, but he isn’t exactly one of them, and of course few actual Englishmen would consider him one of their own. He is seen by both sides as the other. Even though his work might sound foreign to most Western readers, his foreignness is the tip of the iceberg, that humongous iceberg of the other. Or, if there is such a thing as an otherness scale, then Salih falls at a point along this scale, but not at the far end, and maybe a lot closer than you think.

No matter how bleak things look these days, what with Trump and other racists yelling on the airwaves and committing overt acts of violence, we are living in a time of greater inclusivity than any other. More people are being allowed into the dominant culture, more people are being allowed to talk, maybe not all at the same volume, and there are still not enough voices, but things are quite a bit better than when Salih and Baldwin wrote their novels, and that is reflected in our literature. Every year, novels by women, African Americans, Latinos, queers, by all kinds of “others,” are released alongside the white-male-authored books. We have novels by Somalis, Filipinos, Chinese, Indians, Peruvians, Nepalis, you name it.

World literature is now a genre. And as you might have guessed, I have a problem with this.

Let’s take an example: Which Chinese writer gets to talk? Amy Tan was born and raised in California and still lives there, so at times she’s a Chinese-American writer. Yiyun Li lives in the United States and received her graduate education here, but she was born in China; she’s definitely classified as a Chinese writer. They both write in English. Ma Jian lives in London but writes in Chinese. Mo Yan is Chinese, lives in China. He has been accused by the West of not being sufficiently anti-government, which basically means he does not get to speak for the Chinese. Liu Xiaobo was born and raised and jailed in China, but he was a critic and academic, and who reads that?

It might be fun to play Who Is More Chinese, but that’s not the point here. This isn’t about good or bad. I love the work of all the writers I mentioned above. What I’m interested in is who gets to talk. Arguably, Tan and Li are the only “Chinese” who are allowed to talk, who are allowed to tell the story in the United States. There might be one or two others. This is still very limiting, not just in terms of how few are permitted to speak but how the writers are perceived. We’re adding another modifier, creating another box—black writer, queer writer, and now the world-literature writer.

On the back cover of one of my novels I am called “one of world literature’s most celebrated voices.” (I have a voice, I get to talk, though I often have the impression that I’m supposed to do it sotto voce.) If we look at the impressive list of writers who are part of this world-literature thing, we see Tan and Li, Aleksandar Hemon representing Bosnia, Junot Díaz representing the Dominican Republic, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Teju Cole representing Nigeria, Hisham Matar for Libya, Daniel Alarcón for Peru, Salman Rushdie for India or is it Pakistan, oh, what the hell, let’s give him the entire subcontinent. I get Lebanon.

The thing is that we are all Westerners, if not exclusively American. We have all been indoctrinated with a Western education. We can cite Shakespeare with the best of them.

A number of years ago I was a juror for the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, an award sponsored by the University of Oklahoma and the magazine World Literature Today. Since this is an international prize, the jury is always composed of international writers. There were jurors representing Lebanon, Mexico, Egypt, Nepal, Palestine, South Africa, Ukraine, the Philippines, and Italy. Only the Italian actually lived in Italy. The rest of us were primarily Americans, living in the United States, almost all associated with American universities. The Mexican was a Texan, the Egyptian a New Yorker; the Nepali taught at Ohio State. Every interview I did as a juror included questions about peace in the Middle East and whether we can achieve it in my lifetime, what it is like in Beirut, and whether I found the trip to Oklahoma tiring. Norman is a four-hour flight from San Francisco. (And while we’re talking about universities: MFA programs are a kind of indoctrination, too. Certain stories, certain types of stories and certain ways of telling stories, are made more valid than others, and this can be dangerous. From the Congo to the Punjab, if you go to Iowa, you will be learning the Iowa Way. You risk becoming a purveyor of comforting myths.)

This is not a discussion of authenticity. I’m not sure I believe in the concept, particularly in literature. Think of Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient, a fully imagined novel with four “other” characters set in “other” locations. Nabokov did not have to be a pedophile to write Lolita. After all, art and artifice are related. What I’m talking about, in my roundabout way, is representation—how those of us who fall outside the dominant culture are allowed to speak as the other, and more importantly, for the other.

This is not to say that we were not, or are not, “world literature.” We might be different from what passes for regular American lit, or as I like to call it, common literature. What I’m saying is that there is more other, scarier other, translated other, untranslatable other, the utterly strange other, the other who can’t stand you. Those of us allowed to speak are the tip of the iceberg. We are the cute other.

I use the term jokingly, but also deliberately. All of us on that world-literature list are basically safe, domesticated, just exotic enough to make our readers feel that they are liberal, not parochial or biased. That is, we are purveyors of comforting myths for a small segment of the dominant culture that would like to see itself as open-minded. I don’t mean that as an insult—I love to be read; we all do—but we are serving a purpose that we might not be thinking much about.

In a New York Times review, one of my novels was called a “bridge to the Arab soul.” I find this phrase discomfiting, mostly because of the words “Arab” and “soul.” Is the Arab soul like the American Way? Do Arabs have just one soul, and if so, can someone please tell me how to find it? “Bridge” I understood. You see, my novel was seen not as American but as representing the Arab world. My novel is a bridge to this world of otherness. I get to talk because I am the bridge. No one on the other side of the bridge gets to. And truly, who would want to cross that bridge and touch the heart of darkness, be soiled by that dark other?

We get to talk because we are seen as the nice tour guides. We can hold the hands of readers of the empire as we travel a short distance onto the bridge and get a glimpse of what’s across it, maybe even wave at the poor sods on the other side. We make readers feel good about themselves for delving into our books because they believe they are open-minded about the other. We are purveyors of comforting myths.

Now, again, I want to be read. I love holding hands. If there is such a bridge, I’d love to take readers for a stroll along it. I doubt any writer feels differently. What I want is to allow other writers to talk, all kinds of writers, or should I say, more others, more-other others.

The problem today is that this culture we live in is lovely and insidious, able, unlike any that has come before it, to integrate criticism of itself and turn it around faster than Klee’s Angelus Novus can blink. The culture co-opts others, co-opts their culture, makes us cute and cuddly and lovable, but we never integrate fully.

Every group needs to have an other. I don’t know how a society can exist without classifying another as the other. The question for the writers who are getting to talk is where we stand. Inside, outside, in the middle? For so-called world-literature writers, it’s a troubling question.

You might think this is diversity, but it seems more like homogenization. Sometimes, not always, when I read a novel presented or marketed as “foreign,” I feel that I’m reading that common thing, a generic novel hidden behind an alluring facade, a comfortable and familiar book with a sprinkling of exoticness. The names of foods are italicized. Instead of visiting Beijing, I end up at its airport with the same bright Prada and Starbucks stores, maybe one dumpling stand in the corner.

And sometimes even that little stand is troublesome. When I wrote a novel about a reclusive woman who bucks society’s rules by having a rich inner life filled with books and art, I was surprised by how many readers identified with her, and more so that many considered her a tragic figure because she lived in a country that had no respect for women. You know: we live in an exceptional country, it’s only over there where they ostracize women who refuse to conform. (Our world might not be perfect, but that other world, that world of the other is just simply horrid.)

How to get out of this cycle? I don’t know. I’m a writer; answers are not my forte. Complaining certainly is. Moreover, as I said above, I’m a writer with a limited view. Like many writers, when I begin a novel, almost all I worry about is making the damn thing work. I move from one sentence to the next, from one section to another, wondering how and whether everything will fit. I try, however, to write in opposition; by that I mean that whenever a consensus is reached about what constitutes good writing, I instinctively wish to oppose it. When I started writing my first novel, a friend suggested I read John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction, which allegedly explained the principles of good writing. I hated it, not because it was bad advice but because it felt so limiting. Writers are supposed to show, not tell? I wrote a novel where the protagonist does nothing but tell. A short story should lead to an epiphany? Who needs that? When I’m told I should write a certain way, I bristle. I even attempt to write in opposition to the most recent book I finished. If my previous novel was expansive, I begin to write microscopically; if quiet, I write loudly. It is my nature. I don’t know whether this childish rebelliousness helps keep my work “foreign.” Most days, I doubt it. I write a book thinking it is subversive, that it might not be a comforting myth, and if it gets read, if I’m lucky, the dominant culture co-opts it like Goya’s Saturn devouring his son.

I might think of myself as living in opposition to empire, or I might insist that I write differently from everyone else, but I recognize that I believe this to make myself feel better. Whenever I read reviews of my work, I notice that I am still the tour guide. “Look at those cute Arabs. See, not all of them are bad. And the homosexuals are nice, too.” Which is to say that opposing the dominant culture is like trying to whittle down a mountain by rubbing it with a silk scarf. Yet a writer must. I may not be able to move mountains like Superman, but I have lovely scarves.