The strangest part of acquiring my green card was the medical exam, which culminated in an inspection of my breasts and “external genitalia.” Underwear lowered to my knees, I stood behind a curtain as the doctor glanced down for a second before nodding his approval. A nurse who’d come in just for this moment, apparently as a chaperone, told me that they weren’t looking for signs of ill-health but only trying to ensure that I hadn’t suffered genital mutilation and, more to the point, that having said I was a woman, I was in possession of the requisite parts. When I asked the doctor what would have happened had my body and my self-description not matched, he paused and—switching pronouns in a manner so delicate as to seem almost considerate—said that he would have had to talk to such a patient “about what they thought they were doing.”

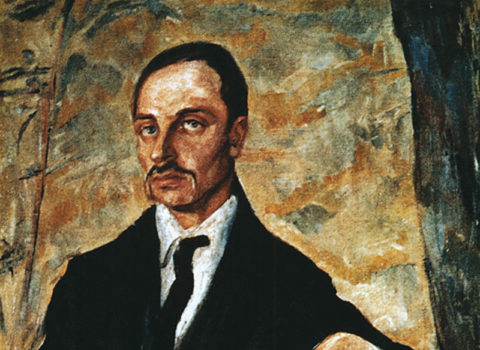

“Ely,” by Jess T. Dugan © The artist. Courtesy Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago. To Survive on This Shore, a book by Dugan and Vanessa Fabbre, will be published in September by Kehrer Verlag.

Those words came back to me as I read Unbound: Transgender Men and the Remaking of Identity (Pantheon, $27.95), a portrait by Arlene Stein of several people who, on a single day at a clinic in southern Florida, underwent top surgery to masculinize their chests. Though the book is by no means a memoir, it does chart the development of Stein’s thinking alongside that of her subjects, and her willingness to explore her own limitations makes it a livelier and more moving study than it might otherwise have been. As a lesbian feminist of a certain age, Stein, a sociologist at Rutgers, insists on questioning anything in the discourse on gender and transition that smacks of essentialism—yet she frequently realizes (and has the grace to say) that much of the rigid thinking she encounters is her own.

It’s true that some trans people may have been forced to embrace simplistic “man trapped in woman’s body” narratives in order to access medical treatment, or to choose one gender box to protect themselves from violence and discrimination. Stein also comes to understand herself as part of a movement that, though keen to throw off many of the trappings of conventional femininity, remained suspicious of anyone who took that too far. She admits to a selfish “sense of loss” at the rise of transmasculinity, a fear of losing potential political comrades and objects of sexual desire to another team as she watched “handsome women transforming themselves into dudes with stubby beards, thick necks, and deep voices.” What’s more, she has to come to terms with having “regarded women—who don’t start wars and rarely beat their spouses, who have smooth skin and tend to smell nice—as the superior sex in many respects,” a combination of fuzzy politics and visceral disgust that made her initially wary of anyone who seemed, in considering a move like top surgery, too eager to “embrace maleness.” Yet what drives her subjects and what they seek from their transition is, she discovers, almost always far more ambiguous.

Stein acknowledges up front some other potential pitfalls: her sample is limited to a few individuals who want and can afford this high-end surgery; one of them, Nadia, who binds her breasts and wants to get rid of them but feels secure in her identity as a woman, is technically not trans at all, raising the issue of where transmasculinity and butchness might or might not overlap; Stein herself, like me, is cisgender, and so must address the age-old problem of the outsider anthropologist. Still, by allowing her subjects to speak for themselves as those selves are reinvented in various ways, Stein leaves room for productive contradictions to appear.

She notes that very few people who transition medically regret doing so—and, crucially, that isn’t the same as saying that gender confirmation surgery is a matter of neatly and at long last moving into the category that correctly corresponds to your one true self. It’s striking that Stein’s subjects, self-questioning throughout, tend to become only more open-minded after modifying their bodies. Parker, a trans man who starts out channeling Fight Club’s Tyler Durden and dreads aging into a “little old granny,” mercifully opts to cool it on the machismo after his surgery. “I don’t say ‘bitches’ anymore,” he tells Stein. “I can relate to women more now than when I was a woman.”

The subjects of this book readily discuss their experiences of newfound male privilege—one of them, favored over a female colleague for expressing the same idea, observes that “if a guy says it .?.?. it must be true.” They also note the complexities of that privilege: people of color who transition acquire new problems that no “white dude” need worry about; in some neighborhoods it may be safer to walk around looking like a butch woman than like an effeminate man. Parker moves from a single-minded focus on joining the boys’ club to fears of “betraying my feminist roots” by implying that it’s less desirable to be a woman. He makes thoughtful videos of his changing body and posts them online.

Stein’s choice of Florida, where, the humorist Dave Barry has joked, plastic surgery might as well be the “official state hobby,” seems apt. (She reports that only New York and Los Angeles do a more booming trade in cosmetic surgery.) It’s a place where the less controversial form of boob job significantly outnumbers these masculinization surgeries—breast augmentation is the most common cosmetic surgery in the United States, routinely bringing in a billion dollars a year, and needless to say, you don’t need to work nearly as hard to justify having it. Presumably that’s because, as one psychologist tells Stein, breasts are “so sanctified” in American culture that it’s well-nigh impossible for the powers that be to conceive of anyone not wanting them.

Stein quips that, “with my unvarnished middle-aged face, unshaven legs that peek out from under my khaki shorts, and upper arms that are beginning to sag,” she feels like “a fish out of water” in Fort Lauderdale, with its “svelte receptionists” sporting “full lips, ample bosoms, and no discernible wrinkles.” In Florida (Riverhead Books, $27), the much-garlanded, best-selling novelist Lauren Groff’s new collection of thematically—or perhaps I should say atmospherically—linked stories, the “low, flat, and wet” region where Stein’s subjects go to remake their bodies begins to emerge as a character in its own right.

Though Groff moves adroitly through an impressive range of lives, times, and places, the stories often seem propelled more by a supercharged pathetic fallacy than by action and character. The storming, punching, chasing rain alone displays a frightening autonomy, while the landscape and fauna seem to make metaphor on a monumental scale. At moments it’s as if all Florida has been invented just to liven up the kitchen sink—what better image of sneaking marital discord than a snake in the toilet bowl?

Borders between lives and physical spaces seem unpredictably porous. Children are left alone in houses overrun by other creatures; adults slip into sickness or homelessness; the weather scatters objects and people, throwing them together to witness the debris of one another’s lives from unexpected angles. After a storm, the narrator of “Eyewall” sees “towns flattened as if a fist had come from the sun and twisted”; she hears that “someone found a novel with my bookplate in it sunning itself on top of a car in Georgia” and also that the high school basketball team “crossed a bridge and was swallowed up by the Gulf.” The book stages an intriguing relationship between the individual and the collective, so that a house or campsite or town can resemble a shared bad dream. Climate change, though explicitly addressed only in glances, is a palpable threat, given a force still unusual in fiction by a treatment that makes it hard to distinguish from interior phenomena.

Like the past, Florida follows Groff’s characters wherever they go. The pages are full of cascade, swamp, and drift; everything and everyone seems on the slide. In the final story, a woman takes her two sons, aged six and four, to France, where she intends to work on an ill-defined project about Guy de Maupassant. But the days slip by in a threatening, hungover haze. And no sooner do they arrive than she realizes that

Paris has become somehow Floridian, all humidity and pink stucco and cellulite rippling under the hems of shorts. It is ten degrees warmer than it should be, much brighter and louder than the Paris that lives in her memory. She had always thought this would be the place to be during the climate wars that she sees looming in the future. A city of water, surrounded by fields, temperate and contained.

Instead, the reader senses that the refuge of the mind has been invaded, and is beginning to flood.

Even in its more temperate days, France could be a hothouse of gender experimentation, as Rupert Thomson’s eleventh novel, Never Anyone but You (Other Press, $25.95), reminds its readers. Thomson tells the story of Claude Cahun (née Lucie Schwob), the photographer, writer, and pioneer of self-invention, and Marcel Moore (aka Suzanne Malherbe), her lover and collaborator, from Moore’s perspective, rendering it a sleek, lush romance. The effect is often uncanny—it’s a deftly conventional treatment of a stubbornly unconventional subject.

Cahun and Moore fell in love in their teens and were able to remain in proximity after the marriage of Cahun’s father to Moore’s mother. They consorted with the likes of André Breton and Salvador Dalí; they worked together on fascinating portraits in which Cahun appears in many guises, shaving her head and eyebrows, scattering limbs and endlessly rearranging herself (an artful precursor to the shape-shifting transition videos posted by Arlene Stein’s subjects); and they put equal amounts of playful ingenuity and striking physical courage into their resistance campaign against the Nazi occupation of their adopted home, Jersey, for which they were condemned to death in 1944. Thomson’s Moore describes how they wrong-foot their guards and interrogators: the more matter-of-factly they tell the truth (they’d worked alone and had no ties to the organized Resistance), the more firmly their captors believe that it must be an elaborate lie; the more hostility they endure, the greater their affectation of good cheer. (“My room is extremely comfortable,” Cahun says when the two are at last allowed a brief glimpse of each other. “And the view is wonderful,” Moore agrees. “The staff are very helpful, aren’t they,” Cahun chimes back in.) Both survived, in what it seems only slightly whimsical to call a triumph of performance art.

Thomson’s is an extraordinary and rollicking tale, occasionally slowed down by his need to make sure that readers are getting the message. Cahun must patiently explain “the concept of the scapegoat, and about hypocrisy and prejudice” as she lists the villains in the Dreyfus Affair. (Stein’s book faces a similar challenge, trying to speak both to those knowledgeable about and invested in the lives of trans people, and to those for whom the terminology and central questions may still seem foreign.) “In the world in which we lived,” Moore observes, “women didn’t exist except in relation to men. If a woman stepped outside the confines of the behavior assigned to her gender, it could be seen as a symptom of madness.” Cahun praises the poet Robert Desnos for his understanding that identity “can be consciously assembled, like a jigsaw” and for showing that “the two genders are contingent, and interchangeable,” making it possible to “loiter in the twilight territory between the two.”

This is, of course, exactly what Cahun was known for doing. Many of her self-portraits—as aviator, conjoined twins, alien with extended skull—remain irreducibly eerie despite their playfulness. The novel’s imagery, too, feels vivid, heightened, though a bit less surprising: a woman naked but for a headscarf and slippers at the typewriter, her “brown skin gleam[ing] in the lamplight” like the barrel of the gun beside her; a man holding a lit cigarette as he coughs blood down his military uniform, making “red holes in the snow”; lovers at daybreak “like a photograph developing”; a missing breast replaced by an imaginary apricot.

Cahun and Moore’s is a beautiful love story that deserves to be better known, but it’s a little jarring to encounter it via the kind of linear narrative that makes and relies on stable meanings. “I refuse to allow myself to be defined by a few biological characteristics,” Thomson’s Cahun announces. “When I stand in a room by myself, I’m not standing there as a woman. I’m a consciousness. An intelligence.” It’s an appealing sentiment, and yet, said that way, it doesn’t quite convey the force that some of her own writings can have. There she can be both more direct and less pinned down: “Moi-Même (faute de mieux): La sirène succombe à sa propre voix”—“Myself (for want of anything better): The siren succumbs to her own voice.” The question of what they thought they were doing never loses its fascination, but it inevitably grows a little less compelling when they must spell it out for readers than when, as in Cahun’s self-portraits, you get to watch it happen—with all its feints and tricks and disavowals, and without explanation—before your eyes.