The family was informed they would be moving to a place called Montana. Jaber Abdullah had never heard of it, but a Google search revealed that it was mountainous. Up to that point, he and his wife, Heba, had thought they’d be moving from Turkey to Newark, New Jersey. The prospect of crime there concerned Heba, as she and Jaber had two young sons: Jan, a petulant two-year-old, and Ivan, a newborn.

Montana sounded like the countryside. That, Heba thought, could be good. She’d grown up in Damascus, Syria, where jasmine hung from the walls and people sold dates in the great markets. These days, you checked the sky for mortar rounds like you checked for rain, but she still had little desire to move to the United States. Basel, Jaber’s brother, a twenty-two-year-old with a cool, quiet demeanor, merely shrugged.

Jaber, for his part, grew excited. He loved the outdoors, having grown up farming and hunting in a small village near Mount Abdulaziz, in northern Syria. And the mountains would not have the searing heat of their last home, Adana, Turkey, where a frustrated resident once tried to shoot the sun. He liked the idea of his children growing up with American opportunities; however, he was worried they would feel like strangers. The family was Kurdish, an identity they clung to dearly. Jaber once said being Kurdish was “something special.” But their new home wouldn’t offer much in the way of Jaber and Heba’s culture. “The last best place,” as Montana is sometimes called, is 89 percent white. More than 6 percent of the population is Native, but it’s the least black state in the nation, and just 2 percent of the population are immigrants. This demographic homogeneity has attracted militias, Patriot groups, and white supremacists such as Richard Spencer, who resides part-time in the ski town of Whitefish.

On January 16, 2017, two days after the official charged with arranging refugee travel for the US Department of State handed them their documents, the Abdullahs boarded a plane. They brought just a few suitcases of clothes. Basel carried on his baglama (a stringed instrument akin to a bouzouki) so that the wood wouldn’t warp in the baggage hold. They stepped off the plane in Missoula and saw brightly colored jackets, a giant poster advertising catch-and-release fly-fishing, and enough taxidermy to fill a wing of a museum—the Missoula airport more closely resembled a ski lodge than an international hub.

Jaber wore slim jeans and a crisp fade haircut, an appearance that belied his rural roots. Over the years he’d worked as a farmer, a stone crusher, a cook, a dishwasher, a cement layer, a falafel-delivery man, an arborist, and a canary breeder. Now he was twenty-eight, with a big laugh that revealed a missing lower tooth. Heba, who was twenty-five, loved poetry and fashion. She had a round face, a mole on her upper lip, and expressive eyebrows that often signaled dismay at Jaber’s sudden decisions. After they fell in love, he downsized the flock of canaries he tended from forty to eight, a more reasonable number. In March 2014, sixteen months after their marriage and three years after the onset of civil war, they sold everything they owned and fled their home in Qamishli, a Syrian city on the Turkish border with a large Kurdish community. The birds stayed behind.

Jaber made the trip first, running across the border with a group of about fifty men as guards fired into the darkness around them. Heba and Basel followed two months later, paying $5,000 each to a smuggler who had paid off the guards. The cost was necessary: Heba had given birth to Jan just twenty days earlier, and Basel, whose legs were partially paralyzed from a factory accident, struggled to walk on the desert rock. They met Jaber in Adana and joined a vast line of refugees seeking resettlement in a third country. Basel’s disability eventually proved a blessing, propelling the Abdullahs to the front; they waited less than three years. Ivan arrived. Born in Turkey to Syrian parents, the boy was stateless, so Heba and Jaber chose a name that could travel. There were Ivans in Syria, Turkey, the United States, and Europe.

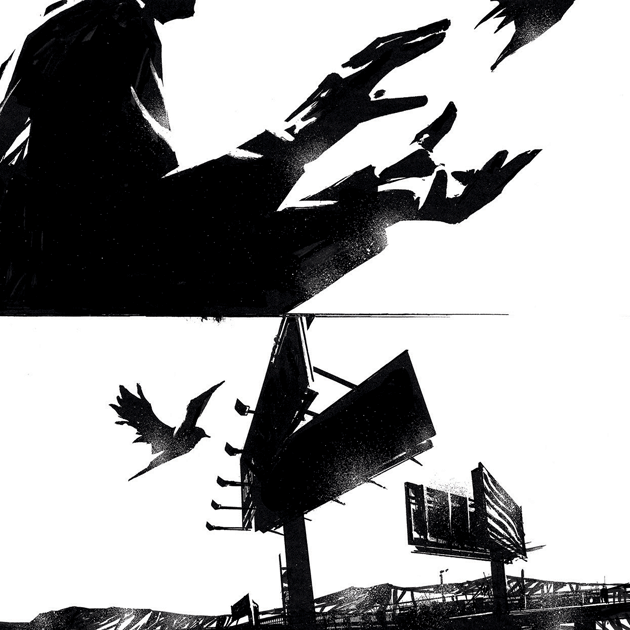

Now Jaber watched the baggage carousel slowly spit out their suitcases. A representative from the local refugee agency was supposed to meet the family and give them a ride to the Motel 6, but no one had yet appeared. Jaber wandered over to a glass case not far from the carousel and found himself looking at the largest animal he had ever seen. It was a stuffed grizzly bear, nearly twice his height, with claws the size of human fingers. He imagined great predators roaming the streets of Missoula. Through the airport windows he could see high snowbanks. He and Basel decided to have a cigarette, and the brothers stepped through automatic doors into the night. Jaber lit up, inhaling smoke and freezing air. He felt like a stranger.

The Abdullahs arrived in Missoula thanks to the efforts of Mary Poole, a thirty-six-year-old jewelry maker, former nurse, arborist, and raft guide who has short black hair.* In September 2015, Poole had been breastfeeding her infant son and scrolling through her Facebook feed when she saw a series of photos of Alan Kurdi, the three-year-old Syrian boy who drowned that month near Bodrum, Turkey. The boy was lying on his belly, with his face tilted slightly to one side. It was as though he were napping. Poole looked twice, then again. A closer viewing showed that his nostrils were covered by tidewater, his sneakers sodden from the sea. The next photo showed a Turkish official carrying the child. He held him just as Poole carried her own son. She imagined the chain of events behind the images—an overloaded boat in the night, a mishap, the boy’s father arriving alone onshore—and began to cry. Her tears alarmed her; anyone who had seen her peel the hide off a deer could attest that she was no bleeding heart. This was a new feeling, jagged and urgent. She thought: I must help those poor drowning people.

In the months that followed, Poole led an effort to establish a resettlement program in her hometown in response to the ongoing migrant crisis. Her naïveté both spurred her on and shielded her from the limits of her experience. She thought it would be simple to bring refugees to Montana.

In the months that followed, Poole led an effort to establish a resettlement program in her hometown in response to the ongoing migrant crisis. Her naïveté both spurred her on and shielded her from the limits of her experience. She thought it would be simple to bring refugees to Montana.

When Poole started googling “refugees,” she did not know that, according to the United Nations, Alan Kurdi was not one—his family had not submitted a formal application. Those migrants who obtained refugee status and sought entry to the United States often found themselves stalled in an extensive vetting process. And even after approval by this byzantine system of governments and international organizations, it often took years to find a new home. On that front, Montana posed a particular problem—it was one of two American states without an active resettlement program. (The other was and remains Wyoming.) Poole knew none of this. She assumed there were dozens of other communities welcoming refugee families in need. “I thought we would be eighty-second on that list,” she told me, “and that we would have to scramble to get to the front.” But there was no list.

Poole called her organization Soft Landing Missoula. She began receiving donations and requests to volunteer; within two months, more than two hundred people had signed on to assist refugees who had yet to arrive. She connected with the Seattle office of the International Rescue Committee, founded in 1933 to aid Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. With the support of the State Department—at the time, the Obama Administration was looking to increase resettlement of refugees, especially Syrians—the IRC agreed to open an office in Missoula. It was the first time in the organization’s history that it did so at an individual’s request.

A thirty-nine-year-old woman named Molly Short Carr moved in from Nairobi, Kenya, to run the office. She was as experienced in refugee work as Poole was green, as circumspect as Poole was bold. One of Carr’s first tasks was to find landlords and employers. Over the past two decades Missoula County has grown by more than 20 percent, to 117,000 people, but finding full-time work can still be a challenge, and Missoula lacks large meatpacking or warehousing industries that attract and thrive on refugee labor. “What do you call a woman with one job in Missoula?” Poole joked. “A lazy bitch!”

Shortly after Soft Landing Missoula’s formation was publicly announced, Poole started receiving threatening emails, and several Facebook groups were launched in opposition to the organization. Forty-five miles south of Missoula, in Hamilton, Ravalli County, hundreds of people gathered in a school gym to air their grievances. A silver-haired preacher dressed in camouflage intoned, “This is about setting the stage so that there will be a battle in Ravalli County, so that ISIS will come for our women. And unfortunately, in Ravalli County, women pack weapons!”

A couple of weeks later, on March 1, 2016, Poole organized an anti-hate march in Missoula. The march was well attended, but the animus was alive elsewhere. Anti-refugee activists had rallied at the county courthouse, and at the state capitol, in Helena. In Kalispell, two hours north, a few white supremacists took to the streets. “I had no idea,” Poole told me, “the hornet’s nest I was stepping into.”

Xenophobia is as Montanan as timber and fly rods. In 1805, when the struggling Lewis and Clark expedition made it to the verdant Bitterroot Valley, just south of Missoula, they were welcomed by the native Salish people. By 1891, however, the Salish had been forced to move north, to what is now the Flathead Indian Reservation. In the late nineteenth century, Chinese miners flocked to the state, drawn by a gold rush, and by 1870 they made up 10 percent of Montana’s population. Irish Catholic, Eastern European, Jewish, and black laborers followed to work on the railroads and in the booming copper town of Butte.

But after the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882, the Chinese population plummeted. Around the same time, the anti-Catholic American Protective Association gained influence in Montana. The APA targeted the Irish, claiming that Catholics would not submit to American law. (This is now a common rallying cry for the anti-Muslim movement.) Within decades, the black population also began to decline, with mobs running African Americans out of small towns via so-called sundown ordinances. In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan opened forty-six chapters in Montana, and by the end of the decade it claimed a statewide membership of 5,100—more than twice the combined black and Chinese population.

Montana is larger than Germany but less populous than Rhode Island, with a landscape that creates the illusion of open frontier. That land, however, is spoken for—and expensive. Charles Schwab, Huey Lewis, an heir to the Hyatt fortune, and the captains of fracking own huge spreads here; so do many other landowners who prefer to be left to their own devices. In the past twenty years, the cities of Missoula and Bozeman have exploded thanks to growth in real estate and tech, while rural counties built on extractive industries have struggled. The cities are blue, most rural areas red, and resentment simmers between them.

The schism is reflected in the state’s politics—the state legislature is conservative, and Montana’s sole representative in the US House is a Republican, but one senator and the governor are Democrats. In 2008, Barack Obama came within 3 points of winning the state; in 2016, Donald Trump won by more than 20. In few other places do these two diametrically opposed visions of America—one extractive, rural, and Trumpian, the other cosmopolitan and urban—exist in such an uneasy balance. Montana also contains the looming presence of hate groups, a small but concerning minority, and anti-immigrant sentiment has entered mainstream politics.

The first refugees were dropped into this climate in August 2016. They were a Congolese family of six. Aoci, the father, a thin, square-jawed man, had scars on his neck from a witch doctor who cut him in a refugee camp in Tanzania. He found work at a small bacon-processing plant. Nyota, the mother, carried herself with a regal air and soon skipped out, filing for divorce and moving to Kentucky with three of their children. Four more Congolese families arrived after that. The women cleaned rooms at a hotel while the men joined Aoci at the bacon plant; they were, however, quickly laid off. Aoci wrote a self-help book for new refugees whose tips included “pay attention to time” and “pray.” Like his fellow Congolese, Aoci was a devout Christian, a fact that the Missoula press trumpeted but that did little to soften opinions outside town. In late August, a YouTube video popped up, attacking Carr for importing “Congloids.”

In September, a local bike shop began planning a Halloween parade. Poole thought about inviting the Congolese families to participate, then decided against it. It occurred to her that they hadn’t flown across the globe for show-and-tell. And the online vitriol was on her mind. She told the bike-shop owner, “Maybe let’s not parade them through town.”

When the Abdullahs arrived in Missoula, they were put up in the Motel 6. Their first days were filled with appointments. The family was told to report to the IRC office after a week for a cultural-orientation session. They were joined there by two Sunni men in their thirties. One, an Arabic teacher from Iraq, had fled Baghdad after being kidnapped by Shiite militias; the other, a Syrian barber, had lived in Damascus until mortar shells destroyed his roof.

The room was an open office space. The refugees sat at a long table with Carr and a few volunteers, among them a silver-haired woman named Jody and an interpreter. Jody and the interpreter presented a slideshow covering everything from education (“The school year runs from August to June”) to flossing (“It’s good for gums”) to language requirements. “The expectation is that you’ll learn English,” Jody said. The refugees would receive $925 per person from the IRC to cover the first three months in Missoula, including rent. They were eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (food stamps) and could apply for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or a matching grant program for adults seeking work.

The volunteers were eager to help the refugees navigate social services and initiate them into the town’s values, but they hadn’t necessarily anticipated their priorities. Jaber wanted to know if vocational training would be provided. “I am a tree butcher,” he declared, explaining his most recent line of work. “Not directly,” Jody informed him—but they would go over healthy eating tips. She showed an image of potato chips and soda next to a red traffic light. The barber asked where he could find halal meat. No one was sure.

When Jody began to get into the minutiae of recycling—Missoula is the type of place where buying a coffee with a disposable lid can get you a reprimanding look—the refugees’ eyes strayed to their cell phones. Eventually, Carr took over. “Have you been watching the news?” she asked. It was one week after the inauguration of Donald Trump, and rumors of anti-Muslim acts were circulating. Everyone started talking at once. “We know about his possible ban on Muslims,” Heba said.

“As long as you stay inside the United States, you will not be removed,” Carr said.

In halting English, Jaber tried to explain to me that his mother, his sister, and another brother were still back in Adana. In the two years the family had spent applying for refugee status, their file had been divided. He waved his hand in frustration, typed something into Google Translate, and held up his phone. “This episode got me real,” it read.

Then Carr made an abrupt transition. “I’m leaving you,” she told the group. “Today’s my last day.” For most of the past six months she had been overburdened, arranging housing and jobs for all the refugees with only a single full-time staffer to help.

That afternoon, news broke of Trump’s first attempt to ban immigration from seven Muslim-majority nations.

In November 2015, two months after starting Soft Landing Missoula and just after the terrorist attacks in Paris, Poole received an email that contained a photo of a man pointing a shotgun at the reader. The text read: “I know what you are. And I will stop you.” Her brother-in-law received a threat on the phone. Soon afterward, a handwritten letter arrived: “It was the white man from Europe that built this once great nation. The ‘people’ you bring don’t count.” At a meeting of retirees, someone asked her how she’d feel if a Muslim raped her. But most of the vitriol reached Poole through Facebook comments.

For a while, Poole made an effort to engage with her critics. She spoke at social clubs and Lutheran churches and eventually alongside a man from an anti-refugee group called Sons of Odin. She reached out online, offering to meet her critics for beers. (A local historian said approvingly of Soft Landing, “They don’t scare.”) One man, a Navy veteran and former private investigator, met Poole for coffee and continued a dialogue online. “One wolf isn’t bad,” he said, referring to Muslims coming to Montana. Ten wolves, though, was a different matter. But he liked Poole, because she seemed genuinely interested in hearing him out, and began to feel differently about refugees after one of the Congolese families moved in next door to him. “The truth is not what you think,” he liked to say. “It’s what you discover.” What he discovered was that the family next door made great neighbors.

But he was an exception. Earlier that summer an Afghan American named Omar Mateen had killed forty-nine people at Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, and after that Poole had found that people were less willing to hear from her. By that time there were at least five anti-refugee Facebook groups in Montana. Wild rumors rebounded in the conservative echo chamber: Walmart was giving away jobs to refugees, President Obama would soon declare martial law, and Mary Poole was getting rich. Around the same time, a rumor spread on Facebook that a contractor in Ravalli County was building housing for Syrians. The window to his truck was shot out, and a homemade doll with a noose around its neck was dropped in his driveway. He found one of his prize 4-H goats dead near his house, then received a text saying, “How did you like seeing your goat hung and dragged to death your next you refugee loving fucker.” In October, another rumor suggested that the government would air-drop five thousand Syrians into a small town called Belgrade, and an aide from the office of Democratic senator Jon Tester took it seriously enough to call Poole. Montana, Poole told me, “is a very conspiracy-theory-prone area of the world.”

Poole was unprepared to handle some of the political attacks against her, especially an onslaught of allegations about an imminent takeover by sharia law. (Sharia—“the way”—is a set of guiding Islamic principles, aspects of which have been codified as penal law in some nations.) Over the past ten years, a nonprofit group called ACT for America has served to bolster anti-Muslim sentiment nationwide by spreading fears of sharia. ACT calls itself the “NRA of national security.” Its chair, a Lebanese-American woman named Brigitte Gabriel, has been a visitor to Trump’s White House, and Michael Flynn, the former national security adviser, was once a member of ACT’s board. ACT has multiple chapters in Montana; it has hosted events attended by prominent politicians, including state legislators and Stan Stephens, a former governor.

In October, ACT organized a gathering in Missoula featuring Shahram Hadian, an Iranian American who left Islam and became a Christian pastor who speaks frequently about the threat of sharia law. At a hotel on the northeast side of town, some seventy people—most of them older, although there was a teenage boy in a T-shirt bearing the image of an assault rifle—came to listen.

The attendees were far outnumbered by protesters on the street. Poole joined the demonstrators, then moved inside, choosing a seat near the middle of the room. She watched Hadian, a squat man in a trim suit, take the mic. He announced that he had come to refute two popular misconceptions: first, that Islam was “a religion of peace”; second, that it was protected under the First Amendment. In short order, Hadian described Mohammed as a false prophet who took hundreds of sex slaves, called Islam an illegitimate religion, implied a connection between Islam and the Holocaust (“Where do you think Hitler got the idea?”), and warned that Syrian refugees affiliated with the Islamic State were coming to town (“They’ve burned the fingerprints off their hands”). He explained that the Islamist strategy for “cultural jihad” was to migrate, populate, and segregate, and worried that soon American women would be forced to cover their bodies. The speed of his oration conveyed a kind of opaque authority—that of someone too busy for actual explanation—and at the end of two and a half exhausting hours many in the audience had the glassy eyes of the newly converted. Someone asked for advice on how to deliver the word of Jesus to a Muslim. Hadian gestured toward the back of the room, where his wife was selling a DVD called Evangelizing Muslims.

After Hadian’s speech, a woman from the audience asked whether Mary Poole was in the room. Poole raised her hand gamely. But as soon as the event concluded she made a quick exit, deeply rattled. Later, she told me, “I got advice: ‘Be careful or someone will get killed.’ Do you play into that drama and listen? Or do you do what you believe to be right?”

Before long, Poole stopped reaching out to her online critics. When Love Lives Here, a nonprofit in Kalispell, asked her advice about inviting a resettlement program there, Poole answered carefully. The decision, she later told me, “needs to be the opinion of a professional, not necessarily the opinion of people who want to help.”

Two days after the orientation meeting, in January 2017, Jaber, Heba, and Basel walked through the streets of Missoula surrounded by a protective shell of volunteers. An impromptu rally in support of the city’s small Muslim population was being held, and it seemed as though half the town had turned out. The Abdullahs held signs citing the Statue of Liberty’s famous inscription—the one about the huddled masses yearning to breathe free—and smiled while fellow protesters with puffy jackets and man-buns rallied around them.

Jaber and Heba thought it was a pretty fine thing, and if they were aware of the guy yelling, “What about the homeless?” or the man with the stand against white genocide sign, they didn’t let on. Basel, who was handsome and single, seemed to be enjoying himself; a number of these pro-Muslim activists were attractive young women. The family paused for a cigarette at a bridge overlooking the Clark Fork River, and a clean-cut man in blue jeans approached. “Can you vote?” he asked. “I’d love to register ’em all to vote!” Someone in the crowd told him that one had to become a citizen to vote, a process that takes a refugee at least five years. He looked crestfallen.

In early February, the Abdullahs moved out of the motel and into a small two-bedroom apartment, with Basel taking the basement. Jenny Montgomery, a former State Department employee who volunteered with Soft Landing and owned a distillery in town, helped furnish the apartment with donated couches, chairs, and beds. The TV, also donated, provided a constant stream of American cartoons designed to teach Jan and Ivan English by osmosis. A prayer rug was offered to the family, but they declined. Though they were Sunni, the Abdullahs identified foremost as Kurds; Heba didn’t bother to wear a headscarf. Above the couch they hung a photo of a raging Montana wildfire.

Once they settled in, Basel posted a profile on Match.com. He had the delicate features and graceful build of a movie star, but to walk he lurched on forearm crutches. With the optimism of youth, Basel chose a sultry photo of himself playing the baglama and wrote that he had a temporary leg injury. Montgomery suggested that he tweak this description for accuracy.

Basel soon got a date with a recent high school graduate named Renae Gosse. Montgomery tailed them on their first date, paranoid that it might be a setup, but the romance was genuine. Basel and Renae began seeing each other regularly, and soon they were hired at a local grocery store, where they made $8.50 an hour.

He also started playing his baglama at Montgomery’s distillery. He sat in a corner, crutches propped on an amp, playing traditional Kurdish tunes while people sipped craft cocktails. He didn’t introduce his songs, so the crowd didn’t know their names: “The World Is a Traitor,” “I Am Strong,” “We Are Journeying on the Long Road,” and a mournful, haunting one called “I Am the Stranger.”

Some evenings at home, the two brothers would sing together, Basel on pitch, Jaber off, Heba and Jan smiling while Ivan, the baby, climbed around the carpet. “Basel has a problem of playing too softly,” Jaber complained. This wasn’t true. Basel’s technique was flawless, his rhythm impeccable. He was reserved and hard to read, a sharp contrast with Jaber’s gregarious optimism. Before long Jaber started playing goalie in pickup soccer games and landed a job working on a poplar plantation designed to serve as a natural wastewater-treatment plant. The pay was $12 an hour. He was thrilled. He worked quickly, cutting thin whips from the trees and replanting them in neat rows, smoking and whistling while he pruned.

His family, meanwhile, remained in Turkey, their resettlement stalled as the courts litigated the Trump Administration’s various bans. They shrugged off the delay, just as they did the daily grind of bad news from Syria. In March, however, when images circulated of the Assad government’s sarin attacks on children, Heba cried. The episode served as a grim validation of their move. “We are here for Jan and Ivan,” she said. She wanted to see them grow up as both Kurdish and American.

Heba had limits, though. When a high-end sleep consultant sent over to treat Ivan for nightly crying told her to let the baby wail until he crashed, Heba thanked the consultant and sent her on her way. Everyone in Qamishli knew that if you let a baby cry at night he would end up neurotic. Like all Kurds, Ivan had to be strong.

Meanwhile, Keith Regier—a Republican state legislator from Kalispell who once compared women to cattle—had introduced a bill to ban “the application of foreign law.” His proposal copied legislation that ACT for America had pushed through thirteen other state legislatures. The bill passed both chambers of the statehouse before Steve Bullock, the governor, vetoed it. Around the same time, Greg Gianforte, a multimillionaire Republican from California and New Jersey with outspoken anti-refugee views, won Montana’s seat in the House the night after punching a reporter at his campaign headquarters.

Nonetheless, Soft Landing carried on. By April, the IRC had brought twenty-three refugee families to Missoula. The refugees endlessly praised the kindness of Montanans. Then they talked about how they couldn’t pay their bills. With Carr gone, the IRC was struggling to arrange housing, jobs, schooling, vaccinations, registrations, and financial support for upwards of eighty people. Soft Landing functioned as a sort of welcoming committee that also provided smaller, but no less essential, services. They organized an ice-skating lesson, procured goats for slaughter on holidays, and arranged for childcare, English classes, and driver’s ed. But there were now 250 volunteers working with Soft Landing, and coordinating their roles became difficult. Sometimes volunteers would show up unannounced at the city’s language classes; at other times, they would overwhelm the local Job Service department. The director of the program, a German immigrant, told me bluntly, “It’s like herding cats. How do you manage two hundred and fifty volunteers with one caseworker?” Poole was aware of the challenges but had no regrets. She often returned to the fact that Montana’s refugees were no longer fleeing war; the kids were safe and attending school. For her, this was enough.

Montgomery worked to make the Abdullahs feel at home. One day in late spring, she drove Jaber, Heba, and the two children north to the National Bison Range, passing newly green hills where buffalo grazed with their calves. They ascended to the top of a hill with stunning views. To the east, they saw the Mission Mountains rising like clean teeth; far below them, the Flathead River was blue with fresh snowmelt. Then, just thirty yards away, a black bear broke into a run. Jaber had never seen anything so beautiful. Back in town, he started to speak about one day owning a home in Montana, a place by the river where he could raise vegetables and birds. Montgomery gave him a cage for four new lovebirds. He named the first pair Heba and Jaber, the second Jenny and Ryan, after Montgomery and her husband.

From the perspective of Poole and the IRC, the Abdullahs were a great success. When Starbucks reached out to Poole to make a branded video about do-gooders, she recruited the Abdullahs to costar. In the resulting story, Heba smiles and plays with her kids while Jaber stands on the side of a soccer field and says, “My dream is to live a stable and safe life.” It was a sweet if facile vision. The Abdullahs’ optimism was convincing because they had little choice in the matter. Montana was not some idyllic canvas on which to project the American dream; it was a life raft.

Once or twice a week, Basel rode a bus across Missoula’s commercial sprawl to a hospital where he met with Mike Tran, his physical therapist. Tran, who is thirty-five, has tanned skin, gelled hair, and biceps the size of logs. He loves Garth Brooks. One day, another patient asked whether Tran had checked Basel “for bombs.” Tran replied that, like most refugees, Basel hadn’t had any say in his destination.

Tran knew more about that than he let on. His father had been among nearly a thousand Hmong and Vietnamese the IRC resettled in Missoula in the Seventies and Eighties. Later, when the local timber industry crashed, many of them left for California or Wisconsin. Tran’s father, a South Vietnamese Navy veteran who married an Irishwoman, was one of a few hundred who stayed. Though Tran was born and raised in Missoula, and was happy with his career, he had never felt at home there. In high school, he was frequently called “chink chink Chinaman” or “gookycrisp.” Fifteen years later, he said, “I still kind of feel like a guest.” Tran’s was a success story; but still, sometimes, he felt something missing.

When Basel showed up at his clinic with a referral from the IRC-assigned doctor, Tran thought of his father. Over his sessions with Basel, he began to tell him about his father’s journey to Missoula, and his own life. But Basel was uninterested in chatting—he was focused on getting his legs back. In Damascus, before his spinal cord injury, he had played soccer and worked in a bowling alley; in the mornings he bowled with his boss. “If I have my legs,” he said, “I win always.” In the clinic, Basel did assisted squats and tried to stand on his own, sweat beading on his forehead. He couldn’t balance for more than a few seconds, but he swore that in the solitude of his bedroom he could occasionally stand without braces. He now felt sensation all the way down to the top of his feet.

Basel could get stronger, Tran said, but the neurological damage was irreversible. Still, for Basel, the occasional flickers of feeling were tantalizing. One day, smoking a cigarette outside the clinic following a tough workout, his reserve melted away. “I want to walk,” he said. “I want to go, like, walking. Everything. Just walking. Myself.”

One day while pruning trees, Jaber felt a sharp pain in his back: a pinched nerve. He was forced to stay home from work. Montgomery hired Jaber to work in her garden, but he refused to accept payment. Back in his village, he said, the neighbors respackled one another’s mud homes every spring after the rainy season. “You helped build my house,” he told Montgomery. “Now I’ll help with yours.”

After a month Jaber’s back healed, and he reapplied for his job, but the position was no longer available. He interviewed to drive a delivery truck, but the company insisted on seeing a record of his employment history. “I have no history,” he said, frustrated. Then he clarified: he had a history. It just didn’t matter here.

The IRC hired more full-time staffers, and by April it had promoted a caseworker experienced with homeless and migrant populations to resettlement director. She soon set up a system for the refugees to give feedback on the IRC’s work. With refugee arrivals ground nearly to a halt because of the Trump Administration’s travel ban, IRC and Soft Landing focused intently on the families already in town. Poole arranged for a stand at the farmers market for women to sell baklava and Ethiopian coffee. Before long almost every refugee family had at least one employed adult. But Jaber wasn’t one of them. When he wasn’t working, he said, “I go crazy.”

One day in early June, Ivan picked up a rug. “Where are we going now?” Heba joked to Jaber. Among many Kurds, it’s understood that if a baby picks up a rug, its parents will soon move.

Jaber laughed, but the suggestion stayed with him. He called a friend from Syria who had been resettled in Indianapolis, to wish him happy Ramadan, and told him about his troubles finding work. His friend suggested he head east. There were fourteen Kurdish families in Indianapolis, he said. The thought attached itself like a burr. The Abdullahs had been insulated from the racism elsewhere in the state; their entire existence was occupied with constructing the foundations of their new life. They liked Missoula well enough, but the thought of Jan and Ivan growing up without Kurdish culture was painful. The family longed for connection to other Kurds, and they had not found them in Missoula.

Heba thought that perhaps in Indiana she wouldn’t be so lonely. For months, she had been too scared to go to the grocery store on her own. “In Syria I had upwards of ten good friends,” she said. “I am sure that out of fourteen families I can find one good friend.” She remembered the dates she would buy at the market in Syria. In Montana, she said, the dates “taste like you need to open them up and pour sugar in them.” The memories of the bear and buffalo at the National Bison Range faded in a moment.

Poole had arranged to give donated cars to the first refugees to obtain driver’s licenses, Jaber among them. The car he received was a donated 1990 Toyota sedan with more than 200,000 miles on it. The hood jiggled, the windshield was cracked and leaky, and the manual transmission lacked a tachometer, meaning he had to shift gears by sound. At sixty miles per hour the vehicle would shake.

“It is a wreck,” Jaber said. But he soon found himself testing it for a cross-country journey. He took the car on drives up a nearby canyon, a popular hiking spot, and convinced himself that the vehicle had hidden strengths. “She is strong,” he said approvingly. By mid-June, it was decided. They would move to Indiana.

Basel would stay behind. “I have my therapy here,” he said, “and my work.” Soft Landing had arranged for him to take a free coding class with a company that might have a job for him. He’d picked up English easily, without taking an ESL class. “I’m smart like that,” he said. But the primary reason for Basel staying in Montana, Jaber knew, was not work or therapy or coding. He was in love. After the family’s departure, Basel would move to Renae’s mother’s house; then he would drive to Walmart and pick out a silver engagement ring.

Jaber returned their donated clothing and furniture to the Soft Landing office. In the second week of July, he gave away the lovebirds. The first pair, Jaber and Heba, had never produced chicks, and eventually Heba (the person) realized the problem: “They are Jaber and Basel!”—both were male. Jaber unceremoniously released the pair near a chain-link fence. He gave Ryan and Jenny, the other pair, to Basel.

One possession the family didn’t relinquish was a motorized toy truck, a birthday present for Jan from Heba and the first purchase she’d made in town on her own. In the family’s final weeks in Montana, Jan ripped around the carpet on the green truck while Heba washed dishes and the Abdullah brothers played FIFA and smoked cigarettes. One hot afternoon Basel took out his baglama. First he played “The World Is a Traitor.” Then Jaber asked him to play “When I’m Poor, You Don’t Look at Me.” And, as always, Basel closed with the haunting, slow “I Am the Stranger.”

Jaber and Heba had saved about $1,500—enough, they hoped, to pay for gas, tolls, hotels, and food on the drive to Indiana. As for the first month’s rent, they would sort that out upon arrival. Jaber thought he might look for a job in a store or restaurant; outdoor labor was getting to be too hard on his body. They packed a few bags of clothes and some extra tires. At four-thirty on the morning of July 26, Jaber and Heba roused the children; Basel woke to smoke one last cigarette with his brother. “Be safe,” they told each other.

Jaber climbed behind the wheel. He steered through town, crossing the great river and turning east onto I-90. He drove the first hour in darkness, the moon obscured by clouds and the mountains that loomed over the highway. Jaber thought of the Kurds in Indiana. “If they move to another state I will move with them,” he said later. “We have a plan to move and live together.” It would be like back home. He hoped never to leave them again. The breath of his sleeping wife and children filled the car. Soon the sun’s first light shone through the cracks in the windshield. He hit the gas.