Discussed in this essay:

Notes from the Fog by Ben Marcus. Knopf. 288 pages. $26.95.

A Girl’s Guide to Missiles: Growing up in America’s Secret Desert by Karen Piper. 336 pages. Viking. $27.

Sight by Jessie Greengrass. Hogarth. 208 pages. $21.

“How hard could it be,” a designer muses of one of her firm’s pet R&D projects, “to finally reach into people’s faces and claw away at what they were thinking.” If anyone can cure you of the rankly sentimental notion that all human creatures yearn to be understood, it may be a writer of fiction. Notes from the Fog (Knopf, $26.95), Ben Marcus’s new story collection, shows a persistent awareness of the violence involved in interpretation—of the difficulty of fully understanding something without in the process destroying it. As crowds of people move around “pursuing tasks they are sure they thought of themselves,” the narrator of “Critique” notes that “very few of these civilians seem aware of their true purpose. Dissection revealed otherwise, of course. Dissection revealed a clear program carried out at what can only be called the cellular level.” This alarmingly pragmatictake on the mind-body problem recurs throughout the book, as parents and bosses and doctors and private investigators and industrial researchers fantasize or strategize effective ways to excavate information, data, meaning, thoughts, and feelings from the frail, pesky human form. “Unless you can rip apart someone’s body and finally know their secrets,” thinks the subject of a medical experiment, “then they are a stranger.”

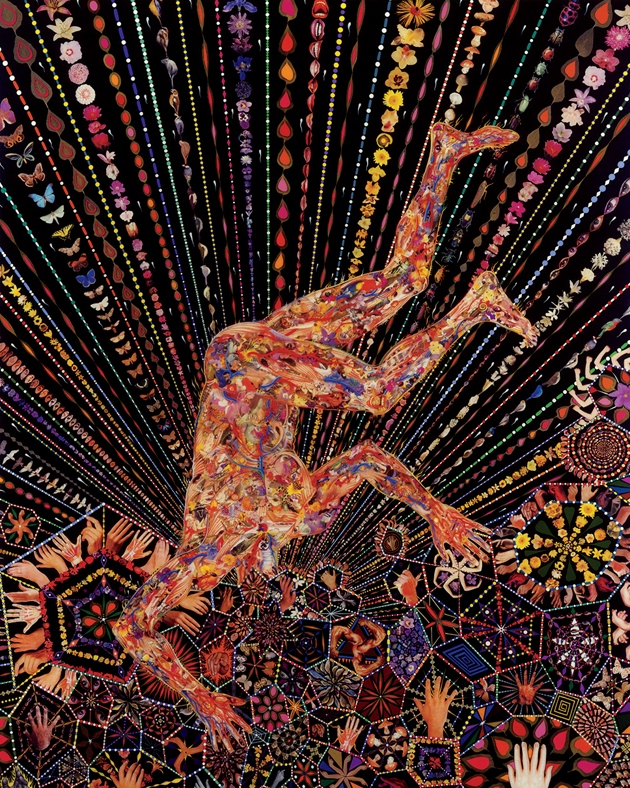

Organism, leaves, photo-collage, acrylic, gouache, and resin on wood panel, by Fred Tomaselli. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York City.

Notes from the Fog adopts a grimly low-tech vision of the future that mostly ignores machines and systems to work directly on bodies. After luring the casual reader in with “Cold Little Bird,” an admirably restrained domestic drama, the collection soon shifts into a gently apocalyptic picture of mass surveillance, medical experimentation, and ecological collapse, taking its sardonic view of family life—self-deluding cruelty and embarrassing neediness and all—along for the ride. During an evacuation from their home on an artificial island, a wife ponders the husband pouting beside her in the driver’s seat: “I never knew that I would be called on so relentlessly to agree with someone.” Another wife, Helen, whose sexless marriage seems to threaten a middle age that’s “just a rotten footbridge you had to navigate, with a creepy old troll beating off underneath it,” shares with her husband an architectural practice with a booming line in memorials for the large-scale terrorist attacks that have become a routine part of American life. Their designs are sponsored by pharmaceutical giants, which, through spouts installed in the monuments, spray clouds of mood-altering drugs to put visitors in an appropriately reflective state of mind. Helen increasingly finds that every commission strikes her as “a future headstone, a kind of sarcophagus that would briefly house living, glistening people before they were lowered into the earth or scattered out over the lake in a burst of powder.” In a third story, a parent administered an experimental substance is left wondering, at the school gates, how to know, “looking at these children, some of them so truly lifelike, which ones were yours.”

As is so often the case, the wilder and more Swiftian the plots get, the more intimately the stories seem to evoke a lived reality. “Critique,” among the shortest of the stories, and the one least clothed in narrative, has no characters at all. Its object of analysis is an ephemeral art installation in the form of a hospital, although the story soon begins to swipe gleefully at its own author, its readers, and the rest of the known world. People “are done badly, all the time, and then soon that is the way people are always done—with bodies and eyes, with feelings, so finally conventional, so deeply unimaginative.” As in the story about Helen, an image appears in “Critique” of a series of graveyards spreading so far as to link together and leave nothing else to walk on. “Certainly there is a critique, in this piece, of waking up, of bothering to live.” And it’s not easy

to escape the feeling that this is a weakness of the project, no matter how profoundly ambitious it is to create a world, build things in it, and then allow life to occur. It is a clear weakness to create an erratic, confusing experience out of time, to give each creature an apparently unique perception of time, and then to make time itself inconsistent, poorly designed, and finally simply too hard to believe. An unfortunate weakness in an otherwise impressive project.

Photograph by José Miguel Ferreira © The artist

Given the considerable range of these stories in tone and scope, it’s striking how neatly their concerns and techniques are prefigured by Marcus’s deceptively simple opening salvo. “Cold Little Bird” is narrated by an unnerved father whose young son abruptly withdraws his affections, refusing the usual hugs and nicknames and in the process expertly exposes the family’s structural hypocrisy, the compulsory humiliations and dominations that masquerade as a free exchange of love. A related thought experiment can be found in Karen Piper’s memoir, A Girl’s Guide to Missiles: Growing up in America’s Secret Desert (Viking, $27). The book, a tale of domestic life on China Lake—the southern California weapons research and testing site—has a brilliantly overdetermined setup, one that yields both black comedy and sickening lurches of insight. Here the child’s classic confusion of scale and the adolescent’s creeping disillusionment are thrown into sharp relief: the subjects families avoid discussing include actual state secrets; humanitarian catastrophe helps keep food on the table; the bobcat kittens Piper likes to watch frolicking outside are doomed after some flooding to breathe in deadly explosives, just as Piper and her sister, who buy candy from the same 7-Eleven as the Manson family, are growing up exposed to unwise quantities of depleted uranium.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Piper’s efforts to escape the mind-set of this militarized theme park and find her own way in early adulthood have mixed results. Like her childhood adventures—on one weekend jaunt the Pipers find themselves driving over a river of live snakes—her attempted rites of passage groan under such symbolic weight that the reader occasionally has to remind herself that this is non-fiction. Piper’s marriage to Keith, a pretentious and untrustworthy Canadian environmentalist, will not work out well. When she first encounters him, in a café in Eugene, Oregon, where they are both pursuing graduate studies, he’s explaining to a friend how one might use dynamite to flood all fourteen dams along the Columbia River: “I’ve devised a system for warning the people in Portland,” he says, “but even if a few die, I say it will still be worth it, eh?” Warning signs proliferate from there. The day they tie the knot, the bride, struggling to cover up a facial welt from a curling iron, sees the weather begin to turn. But this is no ordinary pathetic fallacy—more an inspired Freudian touch, in which her childhood literally looms over her future and gives it a good waterlogging. The clouds above have been laced with silver iodide by the scientists of China Lake, to increase rainfall. They brought this technique to California “after they used it to cause landslides in Vietnam,” she explains, “to fill their reservoirs. To ruin my wedding day. I started to cry.” Some of the guys responsible talk with the same cheery, can-do cynicism of the researchers in Ben Marcus’s stories. “Anything one can use to get his way is a weapon,” a China Laker says, “and the weather is as good a one as any.”

While still a child, Piper naturally isn’t equipped to question the broader context she’s living in, although there is the occasional kids-say-the-darndest-things moment. Visiting a special display on base in which a high-school boy occupies a small bamboo tiger cage to demonstrate Vietnamese torture methods, Piper asks her mother why he’s there. “Because that’s what happens in Vietnam,” she explains, where the United States is at war.

“Why are we at war?”

“Because they do bad things like put men in cages.”

“But didn’t we put him in that cage?”

“It’s just an example, Karen, of what they do. You ask too many questions.”

This subject matter is a gift, a giant joke on the geopolitical import one’s home life can be felt to have, though perhaps it’s inevitable that not all of Piper’s personal anecdotes can quite bear the weight this places on them.

Unlike the rest of us, she was able to find some resolution by researching her parents and their activities in national archives. One of Piper’s finds seems straight out of Ben Marcus. Like the character who envisaged a “system of capture, an extraction tool, for thoughts,” at least one China Laker was at work on a Hidden Knowledge Detector for gleaning “covert mental processes.” Far more than a mere polygraph, this was a mechanism designed to find “what people did not even know they were lying about.”

“Shy,” by Rachel Phillips © The artist. Courtesy Catherine Couturier Gallery, Houston

It’s an idea that would interest Jessie Greengrass, whose slim debut novel Sight (Hogarth, $21) economically addresses the development of the X-ray, psychoanalysis, and modern surgical techniques, taking an approach less humorous than but just as trenchant as Marcus’s to questions of scientific progress, grief, the family, and the body. The blurb on the novel’s back cover seems to suggest that it will, somewhat trendily, be about a woman’s inner conflict over whether or not to have a child. But like Sheila Heti’s recent Motherhood, Sight is in fact far more concerned with how to survive one’s own parentage and one’s own mind, and the way those two projects are connected—with how meaning and understanding can be reached, and at what cost, in life or in art or in science.

A novel, even a philosophical one, usually has an emotional trajectory, and Greengrass’s is framed by death and birth. At both the large and the small scale—in its plot and in its sentences—the book arcs from incomprehensible pain toward uncertain hope. But it often cuts deeper and more precisely than that reading might suggest. The narrator’s thoughts travel in long, sinuous sentences that mirror their struggle for resolution, as when she describes the euphoria that precedes a migraine:

Revelation pended, the veil between myself and understanding was in a constant state of almost-rending, and I thought I could see shadows through it, the outlines of an as-yet uncomprehended truth, until all at once the mania crested and what came out of it, in place of elucidation, was agony, my head pinned in a vice, my body hanging limp below it, a disarticulated sack of bones and blood around which my limbs curled, stiff and liable to snap.

Here again is the violence of interpretation—for the one attempting it as well as its object. The novel’s second section recalls the Marcus narrator who, asked by a detective investigating his father’s disappearance to free-associate in response to proffered images, suspects that “what he really wants to do is climb inside my head and thrust away into the hidden folds of my brain, until some evidence leaks forth onto my face.” Greengrass’s narrator is saddened as a child by premature knowledge of her mother’s unchildish childhood—the mother’s mother, a psychoanalyst known as Doctor K, insisted on extracting and interpreting her daughter’s dreams, prompting her early in life to cease dreaming altogether, and also to cultivate a reflexive secretiveness that affects the next generation. The narrator thinks of Herbert Graf, Freud’s “Little Hans,” initiated too early into proto-adulthood by his own doktor. She pictures the boy’s trust being “opened like a nut, split to see what mechanism it was that made it grow.” It’s a question not of knowing too much but of being shown how little one can know oneself, which Greengrass, like Marcus, links to the risks inherent in sloppy language, sloppy thinking and reading—Graf is cursed by the grown-ups with a horrific “metastasising complexity—an enforced awareness of the unreliability of thought, the way that one thing can come to stand in for another without us noticing the difference.”

Still, Greengrass does leave room for empathy with a parent’s desperate ache to inoculate a child against the pains of sudden, belated revelations or “the half-rotted-through desire for what will come to haunt or hurt her,” and also for the possibility that children may not feel so confident or so secure in the boundaries of their selves and the world to begin with—hence the responsibility to be gentle with our explanations. The resonance of psychoanalysis is exactly in “this excavation, a digging in the dark: precarious, uncertain, impossible to complete.” Greengrass’s narrator visits a beautifully dissected Anatomical Venus, and considers from several angles the problem of having to rip open and destroy what you seek to treat or explain, as in the case of a caesarean section performed on twenty-three-year-old Martha Rhodes in 1767: the swift contraction of her uterus, the “mass of intestines which spilled out into the resulting space,” her death within hours and her child’s two days later. The attempt to understand and care for others is often imperfect, violent. Whether “done” imaginatively or more conventionally, the same recognizable kind of creature is being examined in all three books—one that cannot stop seeking enlightenment and yet cannot reach it safely, or at all.