Discussed in this essay:

Sabrina, by Nick Drnaso. Drawn & Quarterly. 204 pages. $27.95.

Beverly, by Nick Drnaso. Drawn & Quarterly. 136 pages. $21.95.

A young woman has been abducted and murdered. Her killer, before committing suicide, mailed videotapes of the murder to reporters around the country. “It has become increasingly difficult for my voice to be heard above the din of chatter,” he says. “This is only a means to an end.” The tape, despite the efforts of the police, has now appeared online. Do you watch it?

In Sabrina, Nick Drnaso’s fascinating, unsettling new graphic novel, just about everyone says yes. Even before the video leaks, news about the murder is greeted with “link?” and “I NEED to see this.” An office worker waits just long enough to check over his shoulder (and for an ad to load), then clicks play. A conspiracy-theorist radio host notes that the “execution is being downloaded about five million times per hour”—then apologizes to his listeners for not yet having “gotten a chance to study the video too closely” and promises to “do my part. . . . What are they trying to say with this one?”

Calvin Wrobel, the closest thing the book has to a protagonist, watches it, even though the victim’s boyfriend, Teddy, is a childhood friend and is sleeping just a few feet away in the spare room. Teddy is almost catatonic with grief and rage and Calvin is worn out from dealing with him, worn out from his night-shift job, lonely without his wife and child (who left him before the book begins), bored, curious. . . . His moral failure slides by in a few moments—a single page—in a darkened bedroom. Drnaso shows us Calvin’s internet search, the ads that clutter the website where he finds the video, including a garish, cross-eyed Viking offering faster downloads, but not the thing itself. Instead, in a brief series of drab, postage-stamp-size panels, he shows us the results: Calvin shutting his laptop, his hand raised to his mouth; Calvin crawling on the bedroom floor, past his piles of dirty laundry; Calvin hunched over the toilet; Calvin sitting on the bathroom floor, his back against the sink; Calvin staring at the ground. And then Drnaso turns away; we see Calvin’s empty hallway, Calvin’s closed front door. He goes back to bed and is awakened by Teddy’s screams.

“It has become a cliché,” wrote Susan Sontag in Regarding the Pain of Others, in “discussion of images of atrocity to assume that they have little effect, and that there is something innately cynical about their diffusion.” Sabrina is, essentially, the study of one example of such diffusion. It begins just before Sabrina disappears, then follows Teddy as he retreats from their home in Chicago to hide out with Calvin in Colorado. Sabrina is still just “missing,” but it’s been a month, so everyone has begun to assume the worst. The videotapes are received by reporters, and the killer’s body is found in his apartment: he was Timmy Yancey, a scrawny, quiet loner who lived just one block from Sabrina. TV crews descend on Sabrina’s sister, Sandra, and, eventually, on Calvin’s house, in search of Teddy. After the video emerges on the internet, it is seized on by conspiracy theorists, who refuse to believe the murder is real, harassing and threatening Sandra and Calvin (who is especially suspect after he fumbles Sabrina’s name on camera), and even Calvin’s estranged family. But they are rescued by the perverse inevitable: another horror occurs, somewhere else—a young man streams a statement on Facebook, then kills “everyone in a daycare center and himself.” The spotlight moves on, and Calvin, Teddy, and Sandra are left to get on with their lives as best they can.

Drnaso’s great achievement is that he never falls into Sontag’s cliché. He approaches his subject without cynicism, and without assuming cynicism in the characters he depicts. Even the vicious, idiotic conspiracists are oddly touching, so clear is it that they are driven by a kind of strange innocence, a refusal to accept the simply terrible. “I don’t believe something like that could happen,” declares Albert Douglas, the Alex Jones–like radio host. “It’s possible she never even existed. We know the military has access to advanced computer-generated image technology that the public won’t be aware of for another ten years.” Truth Warrior, an anonymous conspiracist who repeatedly threatens Calvin by email, also passes along a story about Palmyra, a Pacific atoll “used by the US government as a secret prison” filled with those who supposedly died in various recent tragedies. “Now,” he writes,

when I see an atrocity unfold on the news, I wonder if the victims are bound and gagged on a flight to Palmyra. It would not surprise me if the dead at Sandy Hook, the Boston Marathon, and Sabrina Gallo were now living together. . . . It helps me sleep to consider these pleasant scenarios.

And even: “I was told that many happy couples have found love on the compound.” This is more than just a stunning example of wishful thinking: it is a new vision of heaven, dredged up from the sludge of the internet.

Drnaso delivers Truth Warrior’s account in a nearly imageless page, twenty consecutive panels of nothing but text, followed by a single drawing of Calvin’s face. It is a startling refusal of the possibilities of the comics medium. And the face itself is all but unreadable: Calvin’s eyes are black dots, his mouth a single thin, short line, with just a hint of a dip in the middle. That’s all we get. We can see Calvin struggling not to react, perhaps, or thinking, attempting to come to some sort of conclusion about all this. But really we are not shown anything—we are merely reminded that it was Calvin reading all this, Calvin who retched after watching the video, Calvin who leaves burgers from Arby’s outside Teddy’s door every night, to make sure he eats. We are invited to consider how he might react, and how we might, and then the scene moves on.

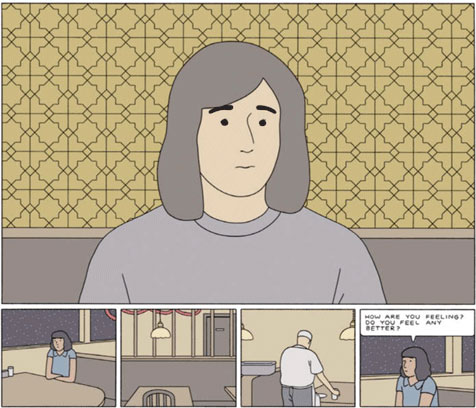

This is typical of Drnaso’s style, which has a kind of subtle, dignified blankness. He uses a thin, even line, with no shading or cross-hatching or texture of any kind, and flat fields of muted, pastel-like color (apparently attained by digitally sampling the colors of various markers). The result is crude and elegant at once, somewhere between Chris Ware, the master formalist of American comics, and clip art, or illustrations for how to deal with a choking victim. Drnaso’s faces, even in close-up, are cartoonish in their minimalism—big black dots for eyes, a few lines for the nose, another for the mouth—but without exaggerating expressions or physiognomy. At most there might be a couple of extra lines of fatigue under the eyes, or a line of strain on the edge of a smile held too long for a photo.

He restricts himself to regular grids of square or rectangular panels, as few as six or as many as twenty-four per page. The imagery within them is often equally limited: whole pages of two people on the phone, or of a man alone on a couch watching TV. Ware has often emphasized the connection between musical composition and comics, the way both are built on time itself, broken down into formal units and rearranged, and Drnaso’s sustained rhythmic control is such that his carefully limited material never becomes tedious. Small panels speed us through the fidgets of a car ride or a Skype conversation; larger ones—close-ups of faces, wide shots of landscapes or rooms, a blast of color from a child’s picture book—pause the action or switch the scene, often just as we are getting oriented. It’s a quiet pulse, far from Ware’s diagrammatic filigrees, but it never lets up.

The first third of Sabrina, especially, unfolds like a minimalist thriller, a suspenseful parceling-out of unnerving information in the guise of everyday life. A mundane conversation about cats, crossword puzzles, and a summer bike trip turns out to be the last time Sandra saw her sister alive. We spend pages watching Calvin pick up Teddy from the airport, drive him home, and show him around his strangely empty house, introducing him to his cat and his gun (“How do you feel about weapons?”), but only learn why it is happening, and who Teddy is, well into the next scene, when Calvin explains the situation to his boss. The discovery of the killer’s videotape, and with it final confirmation of Sabrina’s death, is preceded by four pages of mundanity, featuring characters we will never see again. Reporters show up for work, kibitz about dental woes and the day’s schedule, find the tape in the mail, struggle to locate and operate their antiquated VCR—“Look at that! . . . My kid’s Barney tape. Jesus! I turned my house upside down looking for this . . . Hm. Try ‘channel’ . . . Channel three maybe”—then suddenly go silent. “I . . . um . . . I suppose we should call the police,” offers one. “Um—” says another.

It begins to feel like a series of setups and punch lines, banality unspooled and then cut short by horror. But as soon as we get used to this structure, Drnaso begins to complicate it. The punch lines stop coming, the setups accumulate: Calvin has a gun, and a gas mask; his night-shift job is in the Air Force—he sits in his cubicle in full fatigues, and it is only well into the book that he reassures Teddy (and us) that he’s not a drone pilot but a “boundary technician” working in network security. Every day he has to fill out a form rating his “overall mood” and “stress level” from 1 to 5, declaring whether he is “experiencing depression or thoughts of suicide.” We can feel the “yes” coming as his wife continues to distance herself, the death threats pile up, and Teddy, one room away, alternates between silence and screaming. But it never does. One night Teddy roams the house in his underwear clutching a kitchen knife, and the disaster seems to have finally arrived; he and Calvin stand on opposite sides of a door, and Calvin puts his hand on the knob . . . but then he stops. Nothing happens. Teddy goes to sleep and feels better in the morning. We are left stranded there, on the thin tissue of the everyday—a futile hunt for a lost cat, the promise of a promotion at work—waiting for it to tear. And it does, but not here; the next shooting is in Denver, and comes as a relief.

Artwork from Sabrina, by Nick Drnaso. Courtesy the artist and Drawn & Quarterly

Wordsworth, in his preface to Lyrical Ballads, lamented the “savage torpor” to which the modern world had reduced our minds (“In 1800!” Sontag exclaimed in Regarding the Pain of Others), and that phrase would work as a title for Sabrina or for Drnaso’s first book, a collection of linked graphic stories called Beverly. In both, he lingers on the torpid details—dull jobs, anonymous buildings, aggressively inane conversations, Slankets, malfunctioning vending machines, “porno product placement” campaigns. It’s American life as a kind of desperate void, with savagery rushing in to fill it.

Beverly is driven by ordinary cruelty, familiar indignities. A teenager starting a new job betrays his friendly, painfully awkward co-worker to curry favor with the cool kids. A mother and daughter excitedly volunteer to give feedback on a new sitcom—Drnaso renders it, at length, as a jokeless parade of petty viciousness and empty reconciliation—but are crushed to realize that they are being asked questions only about the effectiveness of the ads. The story ends with the daughter alone in her bedroom, weeping into a pillow.

In “The Lil’ King,” the most baroquely discomfiting of the stories, a family vacation is undercut, and eventually destroyed, by the conflicting fantasies of its participants. The parents attempt to re-create their early romance, with a chipper obliviousness to the indifference of their children—“Well kids, this is where I proposed to mom, twenty-five years ago”—and their teen daughter sulks and attempts to hook up with a nearby college student. Their creepily silent adolescent son, meanwhile, is consumed by elaborate daydreams of sex and violence: a priest and a stripper from consecutive roadside ads screwing in the sky; naked, dismembered bodies littering the seaside streets; an enormous spherical assemblage of dozens of naked men and women, floating above the dock—they look a little like his parents, or perhaps like him and his sister; himself as a shirtless, ski-masked adult, torturing to death the college boys with whom his sister is flirting. All this Drnaso renders with the same dry minimalism as everything else, leaving the reader to decide whether it is amusing or horrendous, typical childhood imagination or budding pathology. Eventually the boy, left alone in the hotel, dresses up a pillow in his sister’s lingerie—and is duly discovered by her, naked and clinging to it, and the trip is cut short in painful silence.

The stories are linked by recurring characters—the sister, especially, is mentioned or appears in all of them. But the unifying force of the book is the destructive potential of fantasy, the violence of its encounter with reality. This is emphasized by the title: the sister is named Cara, not Beverly. Beverly is the name of a masseuse who looks like her, and whom, decades after Cara’s untimely death, her brother goes out of his way to frequent.

In Sabrina the fantasy is real. The killer, Timmy Yancey, wears a black ski mask much like the one in the visions of “The Lil’ King.” We are given a glimpse of his body, after it is discovered by the police. It is in a bathtub, with only his head visible above the bloody water. His eyes are closed, and his mouth is curled in a faint smile of satisfaction, as if he’s having a very pleasant dream.

But Yancey is not presented as an aberration—he is barely presented at all, in fact, seen just once in person, and a handful of times in news reports and online searches. He looks feeble, dorky, childlike, utterly unglamorous; his inner life is not a mystery so much as a simple blank, unknowable and perhaps not worthy of interest. The book’s central horror is not the positive presence of some monstrous, murderous fantasy, but the absence of an alternative—an almost universal inability to conceive of anything else. Violence, real and imagined, pervades the book, a kind of white noise hissing in the background of all these lives. Calvin and his co-workers meet up after work to play a first-person shooter late into the night—“Killing people always puts me to sleep,” Calvin declares; when Calvin and Teddy watch TV, it’s a news story about the 9/11 Memorial (“We want guests to leave with an increased sense of the value of human life”); Sandra asks her sister for help with the crossword: “Twelve letters. We killed the Clutter family.” Each example is anodyne on its own, but the accumulation is nauseating.

The few moments of relief come not in fantasy but in basic human contact, undramatic and often truly awkward. Calvin feeds a burger to a prone, shirtless Teddy, who is “having trouble moving.” A friend of Sandra’s rubs her shoulders and guides her in a meditation exercise: “Breathe in and out. Slow and full. And be at peace.” It seems to work, for a few panels—and then Sandra curls up in a ball and screams.

Later, Sandra gets up at an open mic night and reads from emails she has received from strangers about her murdered sister. Some are supportive, others vile. The last ends, “It’s a fucking lie. It doesn’t make any sense. Where is she?” She is greeted with awkward silence. “I’m sorry,” she says. “I don’t know if this was the right thing to do.” Her face afterward—Drnaso gives it a full half page—is resolutely ambiguous. Eyebrows slightly arched, lips a line slightly bent in the center, eyes black dots as always: Is she sad? Relieved? Embarrassed? There is a lovely delicacy, here and elsewhere, in Drnaso’s refusal to answer such questions. He leaves his character the privacy of her suffering, turns away for a moment to show a waiter picking up an empty glass, a lamp shining above a neighboring table. “Do you feel any better?” her friend asks as snow falls in the darkness outside. “Not really.”