Discussed in this essay:

The Known Citizen: A History of Privacy in Modern America, by Sarah Igo. Harvard University Press. 592 pages. $35.

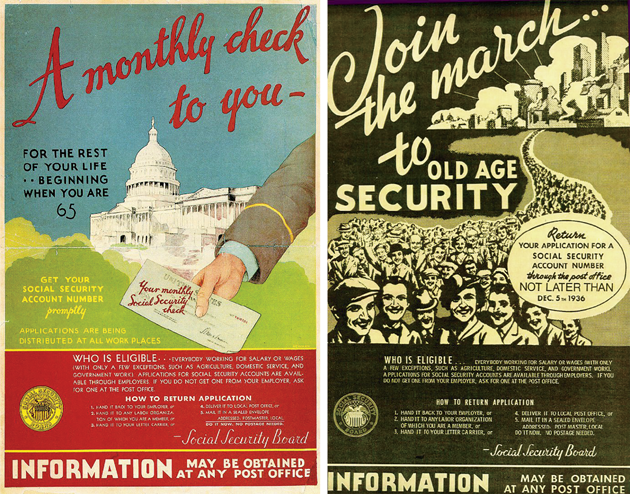

When FDR signed the Social Security Act into law in 1935, he created one of the most comprehensive information-gathering networks in America’s history. The nine-digit Social Security number—the first number to be assigned by the American government to individual citizens—tracked the amount of payroll tax workers paid over the course of their lives, information that was used to determine their eligibility for Social Security. As a system of identification it was unprecedented in scope: it was more comprehensive than the draft and even the census, which collected information only in the aggregate. Yet Americans reacted to the news not with alarm but with enthusiasm. Many wore dog tags engraved with the number or bronze-plated it, while others, in the years before Americans knew much of the concentration camps, had their SSN tattooed on their bodies. Republican critics of the New Deal nevertheless compared SSNs to the identity cards introduced by the Nazis, pointing to the slippery slope of identification that reduced citizens to convicts and prisoners. But these charges failed to stick. Despite the dramatic expansion of the federal government during the Depression and the Second World War, American citizens, enthusiastic about the New Deal and the war effort, were then less concerned about privacy infringements from their government than from their employers, from whom they wanted to conceal their union affiliation, religion, or, for women, their age and marital status.

Posters encouraging workers to register for a Social Security number through the US Post Office (1936–37, left; 1936, right). Courtesy the Social Security Administration Special Collections

Today, this fear of intrusion from the private sector is familiar. It is harder for us to imagine that scrutiny from the government was once welcomed. The story points to the difficulty of understanding privacy’s history—a problem, Sarah Igo writes in The Known Citizen, her excellent new book on privacy in America, that stems in part from our tendency to think of privacy as a static, unchanging ideal. “If we want to understand how Americans in varied contexts and times understood privacy,” she writes, “we need to abandon the notion of it having a stable definition.”

What do we mean, then, when we say we care about privacy? We might mean that we want the right to be left alone, beyond the gaze of other people—to have our private lives protected from public encroachment. Maybe we want to protect a more internal realm of intimacy or secrecy, where we share only what we choose with only those we have chosen. In politics, the value of privacy is associated with the liberal tradition, from Locke to John Stuart Mill, whose ideas are invoked to defend the separation of the public sphere from the private, in which one is free to make one’s own choices without interference. What matters about the private, in this view, is that the choices we make in that realm are our own—they belong to us. If the state fails to protect our capacity to make those choices—if its surveillance, policing, and monitoring of citizens goes too far—it ceases to be a liberal state and becomes something more sinister.

Many of these ideas about privacy are drawn from a canon that was invented largely by liberal educators and historians of ideas during the Cold War as part of efforts to undercut the expanding security state. Conventional histories of privacy tend to associate it with this tradition, and they present a paradox. Some tell the story of privacy’s triumph. Over the course of the twentieth century, citizens wrested their privacy from powerful, bureaucratic states. In the United States, it became a constitutional right in 1965. Thanks to the reproductive and civil rights struggles, it came to be seen as a human right, owed to all. Others tell the story of privacy as one of decline. Privacy is here a thing of the past, caught between the rise of the national security state and Facebook’s data-gathering regime, which monetizes our personal information and turns our intimate conversations into targeted advertising. These two contradictory histories point to our puzzling situation. Most of us worry, some of the time, about privacy. But we also willingly give it up. What does it mean to worry so much about something of which we seem to want so little?

The answer, for Igo, does not lie in “an account of what happened to the privacy Americans once, and seemingly straightforwardly, enjoyed.” Instead, her book investigates how citizens conceived of privacy, and how they responded to threats to their solitude and security. At certain points, “privacy debates focused most intently on incursions into personal space; in other periods, on violations of individual bodies, psyches, data, or peace of mind.” Sometimes citizens craved privacy, but sometimes they happily gave it up. To map these shifts, Igo follows the different ways in which Americans have been scrutinized—in the home, school, and workplace; by the state, the press, and marketing firms, corporations and psychologists, data aggregators and algorithms. While responses to that scrutiny have differed, the questions that have provoked citizens to debate privacy—“who had the right to know, what ought to be publicly known, and who and what should remain unknown”—have been “surprisingly stable.” But what its story reveals are other fundamental transformations in the nature of the social contract—in who gets to count as a citizen and, above all, in the changing legitimacy of government.

Histories of privacy in America tend to begin in 1890, when Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis published an article in the Harvard Law Review declaring a “right to privacy,” defined primarily as a right “to be let alone.” For Igo, however, that decision marks not the birth of privacy but a crucial moment in its gradual development. Before the Civil War, judges and writers alike equated privacy with private property. It belonged to men of land and wealth—to slaveholders, but also to small property holders and heads of household, who reigned over their dependent servants: women and children. Laws against trespass and “unreasonable search and seizure” protected the private space of the home both from intruders and from government interference. A man’s control over how much the public knew of his domestic affairs became a marker of bourgeois masculinity, and so privacy came to signal the propriety of the respectable household. Women were rarely accorded privacy’s protections: they were instead offered the wrong kinds—seclusion, isolation, forced intimacies.

Americans began to make new claims of privacy after the Civil War, as massive private corporations—including news monopolies—proliferated. Between muckraking journalism and new, intrusive modes of communication—the easily read postcard, the telegraph, the party-line telephone—bourgeois men feared they were losing control of their personal information. By 1890, when Warren and Brandeis conceived of privacy as the right to be let alone, they described the circulation of unauthorized images as equivalent to a literal trespass on property. But they also suggested that feelings and experiences were as important as property lines in judging whether an individual’s personal realm had been violated. Feelings could be harmed by “exposure,” by gossip or images, in ways that property couldn’t.

As lawyers, novelists, and others began to defend privacy in these diffuse terms, its protections eventually became more widely available, though this democratization was gradual and uneven. At the turn of the century, police and the burgeoning national security state used new technologies—from fingerprinting to the camera—to gather information, with their attention falling disproportionately on minorities, the poor, and those coded as criminals. To be known by the state was then a mark of degeneracy. During the First World War, worries about conflict abroad became intertwined with the fear of class conflict at home, prompting the government to monitor radical groups as closely as German spies. The war emergency was used to justify the surveillance of the African-American population; in its aftermath, Prohibition allowed police to target many working-class communities. Yet as the United States expanded its surveillance of dissidents, and public and private institutions—from the credit bureau to the gas inspector to the life insurance agent—demanded more personal information, a broader range of people started to defend themselves using the language of privacy, in court cases, “antifingerprint picket lines,” and American Civil Liberties Union campaigns. By the 1920s, not just elites but workers were invoking the right to privacy—meaning, for the latter, the right to be free from scrutiny from above.

What were they worried about? The answer among historians used to be the expanding administrative state, which, during the New Deal, attempted to find out more about its citizens than ever before. In fact, during the Depression and especially the Second World War, government was widely perceived as legitimate. For the New Deal’s beneficiaries, being known to the authorities was part of the bargain struck between citizens and the state. As far as many Americans were concerned, anti-statist Republicans had the wrong target: the danger of being “unidentifiable” was greater than that of state intrusion, the boss’s power more worrisome than the government’s.

It was not until the Cold War that state intrusion came to be feared in a way that more closely resembles today’s. Anticommunist liberals emphasized the value of privacy as part of their defense of the democratic individual against the expanding state at home and totalitarianism abroad. But even then, as Igo shows, for many Americans, totalitarianism and the national security state were too remote to constitute everyday threats to privacy. There were plenty of other fears closer to home. A growing corps of professionals and experts—“big brother in civilian clothes”—were pioneering new techniques of advertising, marketing, surveys, and motivations research that claimed to penetrate the minds of individuals. Students were surveilled at school, consumers monitored in the marketplace; in offices, personality testing was used to locate the ideal, productive company man and screen out the abnormal, the sexually deviant, and the neurotic. The fear of brainwashing mounted. These intruders were not all uninvited: opening up to therapists was seen as part of a healthy and private inner life. But it was becoming increasingly difficult to avoid being known, whether one wished to be or not.

The suburban home was seen by many of its inhabitants as a realm where privacy could flourish, free from civilian intruders and the state. In fact, the state created it: white flight to the suburbs was institutionalized through midcentury programs—from the segregation encouraged by the Federal Housing Administration to the creation of greenbelt towns where families with working wives were barred. This form of privacy required its own surveillance: potential homeowners were scrutinized by mortgage lenders who refused loans on grounds of race, job trouble, bad marriages—each of which supposedly signaled potential foreclosure or financial risk. Even among those who secured a home, the benefits of privacy were unequal; as Betty Friedan documented in The Feminine Mystique, these were not spaces in which women could lay claim to their solitude.

In the 1960s, a series of landmark Supreme Court cases legally redefined privacy as a right to be free from government intrusion. The constitutional status of privacy was first pronounced in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), which guaranteed the right of wives to birth control, overturning an existing statute preventing access to contraception on grounds that the law violated the right to marital privacy. Here the peculiar American association of reproductive rights and constitutional privacy was forged. This moment is often seen as a triumph in the availability of privacy to all. In Igo’s story, it has a more ambiguous status. Foremost, Griswold was not a commitment to reproductive justice or a declaration of the right to private life but an assertion by the Court of a right to “marital privacy.” It designated the marriage bed as what Igo calls a “timeless pre-constitutional privileged space” beyond the state’s reach. Griswold came to symbolize the liberal commitment to a private sphere free from government interference, but it did so by binding privacy again to the family and marital sexuality, not to the individual.

This unequal distribution of privacy’s protection was most apparent in the American welfare state, which is usually described as having two tiers: entitlements, such as Social Security, and need-based welfare programs, which are allotted on the basis of behavior. This division was accompanied by a two-tiered privacy regime. Suburban homeowners with private bedrooms who paid Social Security had a “constitutional shield around their privacy,” one that afforded them freedom from arbitrary interference. Those on public assistance or in public housing had little protection from the “gaze of the state.” Police regularly violated the “sanctity of private dwelling” by entering the bedrooms of unmarried women in “midnight raids to check up on welfare recipients’ living arrangements” and deny assistance to any who violated dominant sexual norms—a practice that was entirely legal until King v. Smith (1968), which ruled that federal family aid could not be withheld because of the presence of a “substitute father” (a man with whom a mother claiming benefits purportedly had sexual relations). The war on poverty introduced a range of “treatment, counseling, training, and rehabilitation programs” that made recipients of public relief subject to new forms of scrutiny. Even with the most progressive forms of social welfare, the old discriminatory politics of privacy remained.

At this point in Igo’s narrative, a conception of privacy similar to our own—in which the defense of privacy is synonymous with the protection of personal choice and information from state interference—begins to emerge. As citizens invoked new privacy rights in their defense, one immediate focus was data gathering: the acquisition and ownership of information became a political question. In 1965, when the federal government, urged by social scientists, attempted to set up a national data center to centralize statistical information and records already held by federal agencies, the proposal prompted such intense public outcry and congressional scrutiny that it was abandoned. In the early 1970s, a series of acts were passed to regulate information gathering: the Privacy Act, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, and the Fair Credit Reporting Act. These reflected anxiety not simply about surveillance but about the existence of permanent records—kept by schools, employers, government agencies—out of reach of individuals. The new laws did not allow individuals to control their information, but they did guarantee that they could view and correct their records, which were held mostly by federal agencies. Corporations were largely exempt: in a striking exception for an age of increasing corporate power, the Privacy Act said nothing about the private sector.

Around the time of Watergate, as data-gathering technologies made it even harder for citizens to control their personal information, those who worried about privacy began to focus less on the ownership of data than on the importance of consent to its collection and distribution, and on regulation by norms of fairness, accuracy, and security. The new political and commercial value of transparency changed expectations of privacy: where in the past elected officials had had some leeway with their private lives, in the aftermath of Watergate, the exposure of secrets became a tactic to make politicians more accountable, as well as a strategy for bringing down enemies. In a newly confessional culture filled with memoirs and talk shows, from An American Family to The Dating Game, agreement about what ought to be private broke down.

This was in large part a legacy of the social movements of the 1960s—from civil rights and the new left to Black Power activism—which redrew the boundaries between public and private by expanding the realm of politics to include sexuality, cultural identity, and power relations within civil society. The women’s liberation movement, in particular, argued that “the personal is political,” insisting that the private was at best a realm fraught with contradiction; more often, claims to privacy allowed for the realities of domestic exploitation and abuse to be hidden from view. Feminists quickly contested the premise enshrined in Griswold that reproductive rights were a private matter and not a matter of political and economic equality, and condemned the belief that rape was a private act, permissible in marriage, rather than a social injustice. These movements often demanded transparency; in their wake, openness, honesty, and authenticity—in politics and relationships; about medical procedures, sexual identity, and family feuds—became strategies for exposing injustice. For many minorities, full citizenship hinged not only on admission to but on visibility within the public sphere. The downgrading of the private was perhaps most explicit in the gay and lesbian movements: those who demanded the right to be left alone and not have their lives policed also recognized that true privacy required making their sexuality public. Coming out was a repudiation of a particular kind of imposed privacy in which individuals were forced to hide their sexuality. Sometimes these repudiations involved controversial means, such as “outing” public figures. For those who suffered from discrimination and unequal social standing, the assertion of a right to privacy could be counterrevolutionary.

The struggle of what to uncover and what to conceal is ongoing, but today it has less to do with the press or the school board than with the corporations of the internet age. Even they have precedents. It is not new for the private to be a realm of profiteering, or for corporations to be parasitic on our privacy. Facebook, Google, and others have taken over the data-gathering functions of advertising and credit agencies, monetizing our lives just as insurance and marketing companies once did. They just do it on a scale that far surpasses earlier efforts.

For Igo, what is new is our lack of control. She isn’t always explicit about how this came about. She is often more interested to show how different ideas of privacy have operated in ordinary life than to explain why they changed over time. But her book can nevertheless help us better understand our own debates over privacy today. Take the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, which this May began to regulate the way in which data is collected and used. The GDPR is not concerned with who owns the data but with transparency and positive consent, which organizations that collect or use data now must obtain from individuals. It seeks to empower individuals and constrain the behavior of both private and public bodies by imposing on them new obligations and giving EU citizens new digital rights. In light of Igo’s account, we can see that these ideas are characteristic of the way concerns about privacy have been expressed since the 1970s. Policies to protect privacy appeal to a language of transparency, individual consent, and rights. But they rarely try to disperse the ownership of our data—by breaking the power of monopolies that collect it, or by placing its use under democratic control through public oversight.

Why not? Igo downplays one answer, which is that our vision of how to protect the private has been shaped by the political process of privatization, the selling-off of public assets and the takeover of public services—from welfare, education, and health to incarceration—by private contractors. This has eroded Americans’ trust in public institutions while increasing regard for the private. The state, once a “beneficent” security provider, is now seen as a bureaucratic “invader.” Igo views this trend as in part a result of a “consumer-driven quest” for more privacy, epitomized by the construction of gated communities and white middle-class Americans’ abandonment of parks and town squares for health clubs, malls, and private schools. But such a focus risks underestimating the role that the idea of privacy itself played in this transformation—and the role it plays in politics in general. Business interests, Republicans, and neoliberal policymakers have touted the market as the guarantor of the private realm and attacked the welfare state in privacy’s name. They have promised not only efficiency but personal choice, empowerment, individual freedom, and control. Just as the appeal to privacy allowed for the continued valorization of the patriarchal family, it has also provided cover for the erosion of the public.

Yet control over our private lives requires a degree of collective control of our institutions that privatization makes difficult. Today, the kinds of privacy that are available to us have narrowed: the personal spaces in which we conduct our relations are not public but the privatized realm of the “social” corporations, where our information is used for purposes that are not our own—the domains of Facebook, Twitter, the news feeds over which we have little control. The only political agent that can break the power of the corporations—the democratic state acting in our name—has been devalued and is no longer seen as trustworthy or able to protect our privacy.

As Igo’s story makes clear, the era when state intrusion was seen by citizens as part of the social contract is over. But if the private is to be a realm of intimate freedom open to everyone, its defense must be tied to a political commitment, both to the democratic oversight of those who profit from it and to privacy’s still-unrealized promise of protection for all. Only through such a politics can we find the right kind of private: one that allows us to be free to find the ways we truly wish to be known.