Noah Klieger sits in a small café in Tel Baruch, a modern quarter in the northeast of Tel Aviv. It is May 2017. He comes here nearly every day for breakfast; breakfast has been sacrosanct ever since the mornings, years ago, when he would wake up on his cot in Auschwitz from the recurring dream of twelve rolls and fresh coffee only to confront the same reality: a moldy piece of bread and a stinking soup made of frozen rutabaga.

He has lived in this quarter for the past twelve years, together with his third wife, Jacqueline. “I don’t actually belong here. This part of town is for the young and the wealthy, and I’m neither,” he says with a smile. He stands five feet four inches tall, with sharp features, his nose slightly bent from his years as a boxer at Auschwitz, and green eyes that are watery but still alert. His gaunt face is ringed by a garland of white hair. We sit not far from his home on Mordechai Meir Street. Noah needs about fifteen minutes to walk the five blocks to the café “ever since I started using this,” he says, tapping the walker beside him. “I have a whole collection of the damn things.” For the past several years he has suffered from a bad case of osteoarthritis of the hip joint. “You’re not a real human being anymore if you can’t move around,” he continues. Even today, approaching his ninety-third birthday, he refuses to give in to frailty.

Twenty-year-old Noah Klieger in Brussels, where he traveled after the liberation of Auschwitz, 1945. Courtesy Noah Klieger

For his entire life, Noah Klieger has been a fighter: for survival, against forgetfulness, for building up the state of Israel as a homeland and place of refuge after the Shoah, and against criticism of Israel, which he considers the greatest and most beautiful country on the planet. Fighting is all he has known. So it is what he continues to do now, against old age and death. “Which, between us, is a stupid idea,” he says. “I’ve already lost the first fight, soon I’ll lose the second.” He is not afraid, though; he has never been afraid of anything or anyone. “Still, I want to stay around as long as I can,” he says, partly out of a sense of duty he feels toward all those who didn’t escape the hell that was Auschwitz. “In the end,” he says, “only one out of ten came out of there alive.” He still paid a price, however: rarely has a day gone by in which he hasn’t thought of Auschwitz. “That may sound crazy,” Noah says, “but that’s how it was, and it’s still the case today. Only death will really free me from Auschwitz.”

Noah loses track of time, speaking for eight hours straight, in meticulous German, one of eight languages he speaks. His voice is thinned by age, but it chronicles, with all the advantages and burdens of a photographic memory, the story of his life, or the many lives he has had: Noah as a child in Strasbourg, France; as a teenager working for an underground Jewish group in Belgium; in Auschwitz for two years; fighting in the Israeli Army during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War; as a journalist, reporting from the historic Auschwitz trials of the Sixties and several Olympic Games. He continues to write nearly every day for the same newspaper he has worked at since the Fifties, Yedioth Ahronoth (“The Latest News”), as “the world’s oldest active newspaper editor.” Above all, Noah’s the driven man who never gave up, who was never able to stop talking about Auschwitz, who swore to himself seventy years ago: If I get out of here alive the world must know, because then all this won’t have been in vain. He continues to confront his memories today, despite the fact that so many of his fellow survivors chose never to talk about their experience again, never to relate the horrors—not even to their children.

Over the course of the eight hours, strangers come up to the table, eager to see Noah Klieger. They bow, pat his back, kiss his hand. Every time, Klieger’s eyes light up. “That’s Noah Klieger,” one man, beaming with pride, explains to his young son, pronouncing it Noach, as in Hebrew. “He survived the Shoah. He was one of the boxers in Auschwitz—he’s a hero.”

Early on the morning of January 15, 1943, a train sets off from a railway platform in the Belgian town of Mechelen. It is the nineteenth deportation train to leave from Belgium, the country to which Klieger moved from Germany with his parents in the late Thirties because they thought that Hitler wouldn’t attack Belgium. In one of the cars sits Noah Klieger, who is seventeen. Over the next two days and nights the train will travel 800 miles to the east. Narrow hatches at the tops of the cars that are covered in wire mesh serve as windows. Each car has one bucket with water and another for eighty men, women, boys, and girls to relieve themselves. At first people still converse with one another. Where do you think we are going? What can we expect there? Noah steps in, young but with a natural authority. What are they going to do? Kill us all? That would be hard to do. A bitter cold settles inside the car. Little by little, conversation dies out. The bucket stays empty for hours, but at some point, inhibitions fall away. Men do the best they can to provide privacy, either standing in front of their wives or holding up their coats, the same coats they will later use to cover their children who are crying from the cold, which puts the men, too, in danger of freezing. Mamele, where are we going? children ask their mothers quietly again and again. Again and again, the mothers answer: Everything will be fine.

After fifty hours, the train slows, it nears a godforsaken place, outside the town of Oswie cim, called Auschwitz in German, on the wide plains of Upper Silesia, now Poland. It is below freezing. There are three main camps: Auschwitz I, a prison camp; Auschwitz II–Birkenau, an extermination camp; and Auschwitz III–Monowitz, a slave-labor camp. At the railway ramp—the “unloading station” for Auschwitz II–Birkenau—the train doors are ripped open to the barking of German shepherds and the shouts of armed SS men commanding the prisoners to hurry. Out, out, quick! This way, move it, move it. Leave your things, you’ll get them later. “We had only been in the camp for a couple of minutes,” Noah Klieger remembers, “before we realized that this place didn’t bode well for us.”

Once all the prisoners have left the train cars they’re driven by kicks and blows to a nearby square, where they are lined up in two columns: one for men and boys sixteen and older, the other for women and children. Every time a new group arrives, a team of doctors is sent out to the ramp to decide by visual inspection which prisoners are fit for work. Children and most of the women are deemed unfit, as are most men over forty. Their death sentences are recorded in writing on lists of names that lie on a table before the doctors. Nearly four fifths of all new arrivals in Auschwitz II are sentenced to death. They are never told.

SS men lead the condemned into a brick building several hundred yards away. In front of the building there are wooden barracks where they are told to undress. Everyone is given a piece of soap and told that after the long trip they will now be allowed to wash up. The guards tell them to hurry, otherwise the water will get cold. Then everyone—women and children first, followed by the men—is led into a large room with showerheads mounted on the walls. The showerheads do not work. In order to maintain calm, signs that read bathing area are written in multiple languages. The room fills with people and space grows tighter. When the nearly four hundred victims packed into the room discover that the “showers” don’t function, they begin to panic. By that time, however, the heavy, airtight door has been closed behind them. Shortly thereafter, the guards turn off the electric lights; the poison gas is highly flammable. The pesticide Zyklon B fills the room. The people closest to the hissing gas leap to the side, the stronger trampling on the weaker in mortal fear. Screams. Distorted faces. The children are the first to fall. In ten or fifteen minutes everyone has died.

A high-ranking SS officer is present for every gassing in order to ensure that proper protocol is maintained throughout. After the room has been ventilated for thirty minutes, members of the Sonderkommando, special work units, themselves mostly Jewish prisoners, are sent in to drag out the heaps of dead, children and the elderly on the bottom—removing any gold teeth, then transporting the bodies by freight car to mass graves nearby. Everything is carried out in a rush. By that summer the two large crematoriums, numbers II and III, operate seven days a week at full capacity, emitting a sickly-sweet odor. In order to erase all traces of the bodies, they are no longer buried in mass graves, as before, but rather burned. Every day, dozens of Sonderkommandos are assigned to shovel piles of ashes into the Sola River, which runs along the side of the concentration camp and has turned gray from the ashes. When given the chance, some Sonderkommandos kill themselves shortly after beginning this assignment.

After his arrival, Noah Klieger is transported on the back of a flatbed truck along with two hundred other men and teenagers to Auschwitz III–Monowitz, the labor camp, which is about three miles away. Down, Jewish scum. Take off your clothes. Everything. Once naked, the men are forced into a roofless hangar. Why? one man asks. An SS man draws his billy club and strikes the man so violently in the head that he dies instantly, collapsing on the ground. Anyone else have a question? It is early morning in Auschwitz; the prisoners stand under a pale blue sky with the temperature nearly twenty degrees below zero. The SS men slide the hangar door closed and lock it. The day passes. As evening falls the men are still standing and sitting in the same place. Their blood freezes in their veins, their limbs are frostbitten. Noah and the other younger, stronger men never sit; they walk in place or do calisthenics. All night long. Slowly but surely, the older men collapse or faint, lying motionless on the ground. The gate is opened at dawn the following morning—fewer than half the men have survived. One of them is Noah Klieger.

“That was the first miracle,” Noah says.

In Tel Aviv it’s early afternoon by now, and he wants to order something for lunch. Noah gets annoyed when the waiter doesn’t see him signal at first. Noah Klieger is not a patient man. He’s been talking for nearly five hours, interrupted only by well-wishers and his wife, who has called three times now on his cell phone. Each time she calls he fishes the phone out of his pocket and stares at it, his finger hovering over the touchscreen before he answers. “Yes, yes, I’m still talking. No, no, it might still be a while.” Each time he hangs up without saying goodbye. They have been together since 1970, finally marrying in 1994. She is seventeen years his junior. It is her second marriage and his third. On their honeymoon they spent a week at the Dead Sea; a week without work or activity is all Noah can stand before getting extremely restless.

Years ago, his wife asked him whether he hadn’t had enough of traveling all over the world to talk about Auschwitz in classrooms, universities, parliaments, and, last year, before the UN. No, Jacqueline, Noah told her, I can’t stop, and you know that. Back then he had sworn to himself that he would talk about it. Then at least take some money for it, like other survivors, she told him. “As compensation, if you will,” he now says. “I completely understand.” But he has never been able to accept money. “Maybe I’m the opposite of what non-Jews imagine Jews to be,” he says, grinning. “I’m a bad salesman. Maybe that’s why I’m in demand, because I don’t cost much.” Noah has earned his living as a journalist at Yedioth Ahronoth since he began working there in the Fifties, shortly after his arrival in Israel. As an Auschwitz survivor he also receives a monthly transfer of 519 euros from the German government. The payments were introduced in 1956 under the Federal Compensation Act.

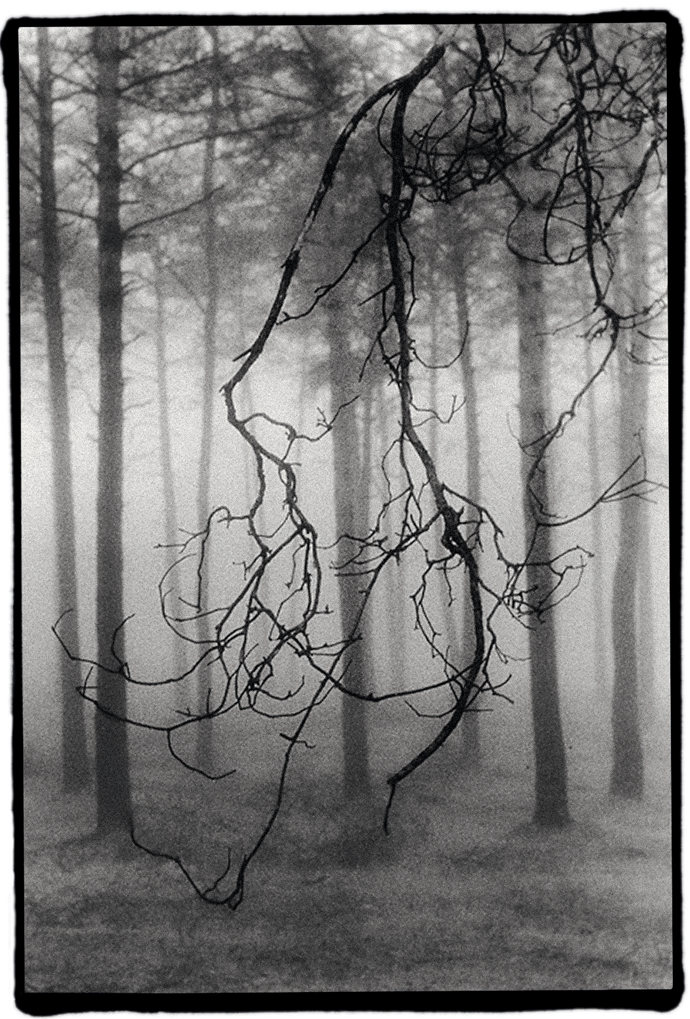

Photograph of the forest outside Auschwitz II–Birkenau by Marcia Lippman © The artist

Still naked after their night outside, Noah and the others are now sprayed with disinfectant and their heads are shaved. They are led to a dressing room, where they are given striped prisoner’s clothing, or “pajamas,” as the SS men call them: shirts, pants, underwear, and caps, no jackets. Each prisoner then has a number tattooed on his left forearm—all those, at least, who weren’t gassed on arrival. The numbers are consecutive; “Höss, the camp commander, was a conscientious man who liked to have a precise overview,” Noah says. Noah’s number is 172345. He is assigned to forced labor for I. G. Farben in Kommando 93, Auschwitz III.

On his second morning in Auschwitz, a second miracle occurs.

Noah is lined up for morning roll call alongside three hundred other prisoners. Three SS officers approach. Which of you beasts can box? one of them shouts into the crowd. Four men, all boxers, raise their hands. Noah debates for a split second: Is it a trap? Raise your hand, his instinct tells him. Even though he’s not a boxer and his only fighting experience was in the schoolyard, in retaliation for the taunt that Jews were too cowardly to fight. Their names are taken down. Four days later they are driven in an open car to a small hall, where they meet their coach. Let’s see what you can do then, he shouts. And if anyone lied, it’s the gas for you. It’s the first time that Noah Klieger has heard any mention of gas. The coach climbs into the ring. He fights with six prisoners. Noah Klieger is next in line when the coach decides he has seen enough. You’re all right. You can fight.

So it is that every second Sunday Noah comes to fight on the appellplatz (“roll-call square”) in front of a thousand SS men and several thousand prisoners. Against real boxers. Luckily, the other boxers always let Klieger land a couple of punches and don’t hit him too forcefully, letting him keep up appearances.

While membership on the boxing team is not a free pass for survival, it does give Noah Klieger a better chance. Every evening he receives an extra liter of soup so that he is able to fight. And every week he has three hours of boxing practice, a brief window into a normal life free from forced labor. For Noah and the approximately 6,000 other prisoners working six days a week, twelve hours a day in Auschwitz III, forced labor is otherwise all that stands between life and death.

Kommando 93, the 200-man work unit to which Noah Klieger is assigned, carries cement sacks weighing more than a hundred pounds for hours on end from six in the morning to six at night, mixing concrete and pouring it into iron molds. There is zero tolerance for slacking; prisoners are forced to keep up a running pace. A fifteen-minute break for lunch.

“On the good days,” Noah says now, “nobody in Kommando 93 perished or was killed.” On the bad days, prisoners would simply drop dead from work. Or a cement sack would slip from someone’s shoulders, usually resulting in an immediate death sentence. Noah never let a sack slip.

The next miracle.

“The worst days,” Noah says, “were those when the SS men felt that they were equal to gods, masters over life and death.” Like the day that a guard hit his German shepherd so hard that the dog spit out its food. The dog hadn’t obeyed the guard’s command to bite one of the prisoners. Enraged, the guard forced the prisoner to his knees with his gun and then commanded him to eat what the dog had spit up. The other SS men broke out into loud laughter. When the prisoner threw up after eating the dog’s food, the guard shot him in the head.

“The people who behaved that way during the Holocaust and Auschwitz did so more or less of their own free will. And no one would have expected punishment even if they refused to engage in such despicable behavior, least of all one that would threaten their lives.

“There could not—and cannot—ever be any understanding or forgiveness for any of them,” Noah says. “They killed six million of us. Six million. They shot mothers in front of their children.” Noah never spoke with Germans from his generation again. And he’s almost glad that he has never come across another SS man. “Because I would have killed him,” Noah says. “Whatever it took. I’m sure of it. And that wouldn’t have been fair to my children, because then, out of personal vengeance, I wouldn’t have been able to be a father to them for a long time.”

But Noah Klieger never wanted children. “There were really only two ways survivors dealt with children,” he says. “Some wanted as many kids as possible, to show God that despite everything they still believed in Him, so that He wouldn’t let something like the Holocaust happen again. But also to show our tormentors that despite all their efforts, they hadn’t been able to kill us off. Then there were those,” he continues, “myself included, who never wanted children. Because we didn’t want to force them to bear the burden of their parents’ story—or maybe just that of their father or mother—for their entire lives.”

“I’m very tired now,” Noah says. “Maybe it’s better that we go on tomorrow.”

In May 1961, as Noah’s editor is planning a special issue on the Shoah, he asks him: Do you think you could travel to Auschwitz for us? No, Noah tells him. I can’t do it. Yet a week later he changes his mind. “I don’t know why I agreed in the end,” Noah says. “But it had to do with the promise I had made to myself. It was one I’ve always tried to keep.”

He lands at the airport in Kraków, Poland, then boards a bus for the two-hour trip west to Auschwitz. Eighteen years have passed since he first arrived by train. With each passing mile the voices of the SS men grow louder in his mind, as do those of the countless dead that accompany him and the daily humiliations he suffered. He sees his former self, a man who no longer resembles a human being. When he gets off the bus, his stomach is so constricted that he vomits.

A young woman leads him and the delegation of visitors through the gate and into the concentration camp. After about three hundred feet Noah detaches from the group. He can’t go on. The tour guide approaches and asks why he has walked off. Isn’t he interested? He looks her in the eye and rolls back his sleeve to reveal his left forearm. She begins to cry. I’ve never seen a survivor.

Noah returns to the camp the following day. “It would have been a weakness that I never would have forgiven myself for,” he says. “And that was how I found my calling.” From then on, he would travel around the world, telling people about Auschwitz. Over the next fifty-five years Noah Klieger travels to Auschwitz another 164 times; he remembers the number exactly.

In April 1944, the boxing team is disbanded. Of the thirty original members, only half are still alive. Despite the extra liter of soup, they’ve died from overwork, from sickness, from abrupt executions, or during escape attempts. But Noah Klieger lives on, fighting a total of thirty-two bouts. He loses every one without exception, but is always able to land enough punches to keep him alive. A couple of weeks later, though, it seems that even his time has finally come. His body, almost superhumanly resilient up to this point, rebels for the first time. He comes down with dysentery and is sent to the camp infirmary. Several days later the building fills with SS men. Selection, they shout. The sick are collected from their beds and lined up in front of the building, where six doctors wait at makeshift tables. Among the doctors is a smiling man with a gap in his teeth, Dr. Josef Mengele, who takes a cursory glance at each of the prisoners through his metal-rimmed glasses. Then, leaning over his papers and without further eye contact, he mutters right or left in a hurried, emotionless voice, waving a finger in the corresponding direction. Right means survival, left means the gas chamber. Noah Klieger is sent to the left. He takes several steps, then stops. A voice tells him that he will die one way or the other. He walks back and stands in front of Mengele, who stares at Noah aghast. The SS men ready their guns. Mengele signals for patience. Is there something else? he asks Noah Klieger. Before Mengele has time to change his mind and have him shot, Noah makes a rushed appeal for his life. Mr. Surgeon, sir, he says, I’m still young and strong enough to be of use to you and the camp. Please believe me. Mengele smiles and shakes his head in disbelief. Do you really think you can still work? Yes, Mr. Surgeon, sir, Noah says. He tells Mengele that he was born in Strasbourg, and that his father was a famous author. “Which was totally beside the point,” Noah tells me now. Mengele raises his hand. Enough, he says. Can we still use him? he asks the doctor next to him. Yes, I think so, the other replies. Mengele tells Klieger: To the right.

“That was the next miracle,” Noah says. “And probably the greatest.”

We meet late in the morning on the second day of the interview, at Noah Klieger’s apartment: four rooms, with the spare furnishings of the elderly. “The noise has been unbearable for several days,” Noah says. The sounds of hammering and drilling come through the walls; they are renovating a room for a caregiver. “For Jacqueline,” Noah says. “Her back pain is too much for her.” His wife smiles. When Noah goes to fetch another walker from a side room, she says: “The caretaker is for Noah. I’m not strong enough anymore to take care of him all the time. But I’d like to let him believe that it’s for me too. Noah has been so strong for his entire life.” Before we leave she puts on his jacket, pulls his collar up, and packs his medicines for hip pain, for headaches, for dizziness.

Half an hour later, Noah Klieger sits at a corner table in Benny the Fisherman, a restaurant on Tel Aviv’s promenade. “They have the best fish in the city,” Noah says. “And the view of the sea from here,” he reflects, looking out the window, “it’s unbelievable. In my opinion, Tel Aviv is the most beautiful city in the world. And Israel is the most beautiful country in the world.” Noah makes no secret of being a Zionist. “It’s our land,” he says. “For two thousand years we dreamed of returning to Jerusalem. And seventy years ago the UN gave it to us, after half of our people were exterminated.”

Noah Klieger leaves Auschwitz in January 1945. The Red Army is approaching, and most of the prisoners still fit for use are relocated to concentration camps farther west. Noah is sent on a death march, first to the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp in Thuringia, Germany, then to Ravensbrück, north of Berlin.

With the sound of gunfire now audible, on April 26, 1945, the prisoners are told: You’re being moved again. After more than two years in concentration camps and weighing barely eighty-eight pounds, Noah makes up his mind. I’m not moving again, he tells himself. Let them shoot me here and be done with it. By April 28 they can hear the rattle of Russian tanks. On the morning of April 29, the Russians march into the Ravensbrück concentration camp. A brief gunfight follows in which several SS men are shot. A Russian officer tells Klieger and the other emaciated prisoners, Comrades, you are free. We are the Red Army. “And that’s how I was freed,” Noah says, his chin trembling.

He makes his way back to Brussels, where he had been arrested by the SS on the way to his parents’ house. Along the way he sees German prisoners of war, their heads bowed, walking in front of Russian soldiers. So that’s what the master race looks like, he thinks to himself.

On a warm day in June 1945, Noah Klieger boards a tram. Of course, he still remembers the line; it was Tram 5. He is on his way to a reception center on the edge of Brussels, for returning survivors.

He’s looking for his parents, even though he suspects that they haven’t made it. There’s no space in the first two trolley cars; he climbs into the last one. Next to him stands a gaunt middle-aged couple. He can feel the woman staring at him out of the corner of her eye. Then, after a couple of minutes, he hears her quietly call his name: Noah. “We were probably,” Noah Klieger says, “some of the only people to survive Auschwitz as an entire family.” His parents moved to Tel Aviv in 1961. They died in the early Seventies, one shortly after the other. Although his father, a doctor of philosophy and law, never fully recovered from Auschwitz, he did write two more books: Der Weg, den wir gingen (“The Road We Traveled”) and Der Himmel rührt sich nicht (“The Sky Does Not Stir”).

Like many of the other survivors scattered throughout Germany and Europe in reception centers, Noah wants to leave Europe. There is talk of the British abdicating their mandate in Palestine in favor of establishing a state for the Jews that will be called Israel. Although immigration is not yet legal, ships have been departing from southern France for some time.

On July 20, 1947, Noah lands in the port town of Haifa aboard the legendary refugee ship Exodus.

“It was the happiest day of my life,” Noah says.

Just a couple of weeks later Noah marries for the first time at age twenty-one. He moves with his wife to Tel Aviv to live with her parents.

Soon after Noah begins work at the newspaper, Yedioth Ahronoth, where he must quickly learn Hebrew. He has written for the paper for seventy years now; the current editor in chief is young enough to be his grandson. Writing has been a passion since childhood, when he published a school newspaper at the age of ten.

He reports on several Olympics, from Helsinki in 1952 to Munich in 1972, and travels the world reporting on basketball, Israel’s national sport. But he also works as a correspondent at the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials that take place in the early Sixties: the accused show no remorse in court. He reports as well on the Sobibór trial in Hagen and the Majdanek trial in Düsseldorf. He still goes to the office on a daily basis, where he writes articles on current events.

Throughout his life Noah Klieger has enjoyed a strong constitution and has been an avid fan of basketball. As a part-time manager, he helped to turn Maccabi Tel Aviv into the city’s most successful club. He holds an honorary doctorate from the University of Haifa and was awarded the French National Order of the Legion of Honor.

“I’ve had an eventful life,” Noah says. “But it hasn’t been a happy one. Many of us were never really able to be happy again. You just can’t get those things out of your mind or soul.”

His cell phone rings. Rabbi Israel Meir Lau is on the line, a close friend of Noah’s for decades. He is trying to convince Noah to take part in the next March of the Living. “You have to come, Noah.” March of the Living was founded in 1988. They visit Auschwitz every year on Yom HaShoah—or Holocaust Remembrance Day—beginning at the gate, walking the two miles it takes to pass the arrival ramp and crematoria and reach the appellplatz.

At first hundreds attended the march, then thousands. It became the largest annual memorial ceremony dedicated to the Holocaust. The survivors always walked at the front of the procession. In the beginning they made up the majority. But slowly they have grown old and frail. Most of Noah’s fellow survivors have died. Noah ends the conversation with tears in his eyes. “I don’t want to leave him there, alone. But I just can’t do it anymore. I can’t travel.”

“Six million [Jews] live in Israel—as many as were killed in the Shoah. That’s something,” Noah says. “That at least will bring me some peace in death.”