Discussed in this essay:

Vile Days, by Gary Indiana, edited by Bruce Hainley. Semiotext(e). 600 pages. $29.95.

Seasonal Associate, by Heike Geissler, translated by Katy Derbyshire. Semiotext(e). 240 pages. $16.95.

The Children’s Bach, by Helen Garner. Text Publishing. 176 pages. $16.95.

How unromantic can a deathbed scene get? A test case: one day in 2015, The New Yorker’s art critic, Peter Schjeldahl, makes his way to the Village Voice’s Cooper Square offices, seeking to rescue the columns he wrote for the alt-weekly in the 1990s from their undigitized obscurity. Let in by a staff member who seems slack-jawed that anyone should be so keen to enter, Schjeldahl observes the paper’s remaining employees: “A very few people, not appearing to be up to much, sat far apart at desks in a dimly lighted panorama of desuetude.” Coda: as summer 2018 gasps its last, so does the Voice; mourned in September blog posts, like Schjeldahl’s for The New Yorker, it now exists only in archival form. This seems a fittingly uncharismatic parable for an East Village that has died more than once in the past thirty years or so—the end doesn’t even get to feel poignant anymore.

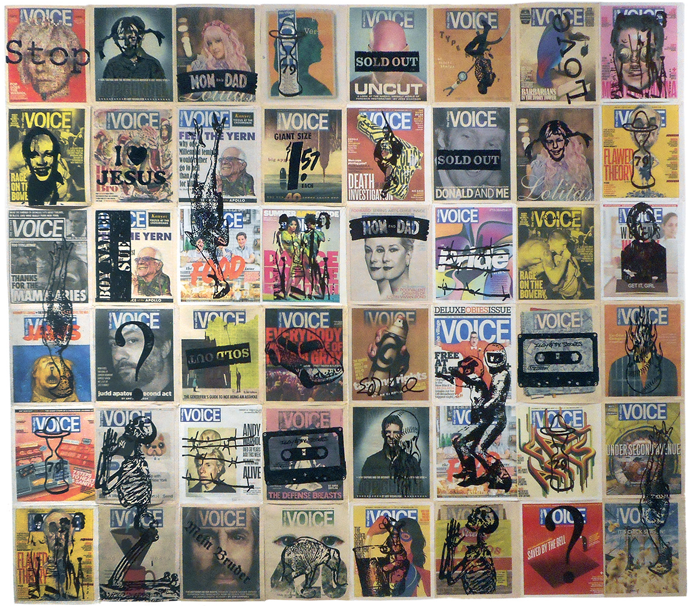

Village Voice Covers, a wood-block print on newsprint, by Nils Karsten © The artist.

Courtesy Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery, New York City, and mhPROJECTnyc, New York City

The few things the Village has going for it today include the far too often underrated writer Gary Indiana, who lived there when, as he puts it, “it still had the narcoleptic desuetude of downtown Detroit,” and recorded its fatal flourishing during the Reagan years, when he wrote the aforementioned Voice art column between 1985 and 1988. Thanks to the poet and Artforum contributing editor Bruce Hainley, who had the same idea as Schjeldahl around the same time, Indiana’s articles from that era have now been retrieved and published as Vile Days (Semiotext(e), $29.95). The collection captures a key moment in the development of the current art world, New York real estate, the AIDS crisis, Indiana’s own writing, and much besides. As these columns were ground out on deadline and to length, the book falls short of the cohesive brilliance of Horse Crazy and Gone Tomorrow, the novels in which Indiana captured the same period, and which have just been reissued by Seven Stories Press. Yet Vile Days has endless compensatory thrills, and an implicit narrative arc of its own.

As well as offering shrewd judgments of artists whose stature has only grown since—Indiana can be equally fervent and persuasive in his analyses of the brilliant, the charlatans, and all those in between—he frequently used the column as a space for experimentation, both formal and philosophical. An intellectual with a precise sense of history, he nonetheless writes with a quality he ascribes to Kathy Acker in one of the articles here: “a liberating, combative irreverence and glee” that puts many other critics to shame. He’s not above shaming them directly, either. Janet Malcolm, for instance, gets skewered for the credulousness and snobbery Indiana identifies in one of her New Yorker profiles: she’ll believe anyone, no matter how corrupt, whose taste in home décor she admires, and her text, he writes,

is studded with . . . novelistic details, which twinkle class assurance from reporter to reader: never mind what X thinks, he or she lives alone in an apartment so messy you and I would never dream of living there. . . . These people are Russian émigrés who serve refreshments in a slobby manner, so I guess you understand how exasperated I felt.

Composite and fictional characters appear. Indiana’s first entry, a characteristic blend of barbed wit and melancholy warmth, asks the reader’s pity for one Gaston Porcile Vitrine, a socialite painter whose “prolific Expressive Jismism” has fallen out of favor, leaving him friendless and broke like so many others in “our fair but unfair city.” One column removes all art-world players’ proper names and shows how little is thereby lost. Others consist of damning collages of quotation, or numbered lists, one of which attacks the reader and the whole scene and city before deigning to share any thoughts on particular shows:

2. This paragraph goes here in order to destroy any notion of continuity in what you’re reading.

3. Fuck you.

4. If I want to tell you something, why drag everything relevant in because “art needs to be covered”? Cover art with a blanket and pour gasoline on it, then light a cigarette and throw the match away. You won’t lose anything you can’t live without.

This, from February 1988, indicates an increasing impatience with the task at hand and the environment, which is confirmed by Indiana’s departure from the Voice a few months after: “bailing out,” as he later put it, in “that leisurely half hour before the aircraft hit the ground.” He leaves on a tellingly serious note that hints at how high he’d always felt the stakes in this milieu to be. After making fun of everyone, including himself, for petty egotism, he turns grave in responding to a potshot from an Artforum writer who attacked him for being “obsessed with AIDS.” Not alone in focusing on “the present health emergency,” Indiana warns any uninfected careerists—flitting about the biennials and churning out Saatchi catalogue copy—whose personal luck has so far allowed them to ignore the dying: “that attitude is not going to play too much longer, even in Peoria.”

080405, by Stan Wiederspan. Courtesy the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art. Museum purchase,

with gift of the artist, Kathleen and Tom Aller, CRST International, and Ann and Henry Royer

Horse Crazy’s narrator, tormented for love of a manipulative and possibly drug-addicted beauty named Gregory, is a writer with a gig similar to Indiana’s. Reading his first column in print, he flinches at the tone, “a middle register between my voice and the voice the dutiful employee inside me thinks is reasonable enough for the audience.” He feels utterly alienated from the self on the page, seeing “someone who never quite managed to live in his own body,” who “expects someone to hit him at every corner, and . . . can’t dance unless he’s had a lot to drink.” Though by no means a recognizable portrait of Indiana as a columnist, this passage aptly describes how paid work can warp and compromise one’s sense of self, which is the central problem addressed in another intriguing new book, Heike Geissler’s Seasonal Associate (Semiotext(e), $16.95), translated by Katy Derbyshire: an account, in an indeterminate genre, of the author’s experience working in an Amazon distribution center in Leipzig, attempting to clear her overdraft when writing and translating weren’t paying enough. It explores what happens, and how quickly, to the psyche of the insecure and dutiful employee.

Read as a novel or as a memoir, Geissler’s book has a few of the weaknesses you might expect, given its subject. The inner workings of Amazon and the experiences of its workers can tell you a great deal about the way we live now. By the same token, it’s not easy for this book to offer much that’s notably new, since reporters have already taken such an interest. What Geissler exposes is also fairly inimical to narrative, since stasis and repetition are inherent in a zoomed-in study of precarious labor and alienation. At first sight, the Amazon premises remind her of a downscale doctor’s waiting room, and the pervasive claustrophobia intensifies when she must visit an actual doctor to get a sick note, confirming the sense that work like this invades all one’s time and space, just as corporations like these keep expanding indefinitely: “You close your eyes and sit in an ocean of time, as though you’d been working at Amazon for years. . . . Your internal screenwriter demands a big closing scene, but none comes and it never will.”

Still, much of the book is chillingly effective, not least for its accumulation of details, which seem both aggressively banal and freighted with an excess of symbolic meaning. The narrator’s preference for unloading and packing books, as opposed to other commodities—remember, she’s only doing this because her writing will no longer support her and her children—loses none of its pathos when you consider that books are quicker and easier to handle. The ubiquitous linguistic debasement and corporate doublespeak is made strange and new again, the small humiliations and injustices pile up along with their psychological and social consequences: “You’re in a so-called flat hierarchy, in which all flat hierarchists are gagging for an opponent.” Structural problems disguise themselves as individual ones; vulnerability and submission are systematized; the signage, training instructions, and manager feedback take the form of incessant low-level bullying: “Anyone who doesn’t lift correctly doesn’t just harm themselves. Sick days harm Amazon.”

Most striking of all are the physical properties of the place itself—the dusty, dingy, poorly organized spaces that stink of sweat, the gray chairs and “worn, greasy wall.” Bodily discomfort, minor but impossible to ignore, always occupies the foreground of the mind, distorting other thoughts and whatever you might risk mistaking for your personality. It’s a salutary reminder that a business need not be failing in order to achieve the grim bathos evoked in Peter Schjeldahl’s description of the Village Voice’s offices. One of the most successful companies in the world looks worse still if you perform the simple trick of viewing it through the eyes of its employees. The firm offers Geissler readymade symbols of oppression and futility that are almost too on the nose, such as the prominently displayed desk made out of an old door. A trainer explains that “the customer is king,” and in order to deliver him his bargains it is imperative to economize elsewhere:

Is it important to the customer that I have a mahogany desk or that he gets what he wants for a good price? Does the customer want us to be sitting here on comfy sofas? Does the customer want to pay for smart offices for us?

The narrator mentally retorts that she, like most other people, is also an Amazon customer, and would nevertheless favor more humane seating.

The second-person narration that dominates is an inspired gimmick, even though diminished in the English, which is forced to ditch the German distinction between Sie and du. (An afterword by Kevin Vennemann notes that Geissler’s pronouns in the original convey infantilizing corporate language as well as the alienated narrator’s attempts to repair her dignity and freedom by addressing herself with basic respect.) Any resistance a reader may feel at the use of the second person, its falsity and presumption, becomes part of the effect. This is not the kind of book that tries to force intimacy, empathy, immediacy via its mode of address. Instead it emphasizes distance, “you” as a role being played. The book in fact mixes first and second person, with Geissler’s voice encouraging the reader to Method-act his or her way into the part of the author during her mercifully brief Amazon period, then occasionally allowing the two overlapped personae to diverge. At first the imaginary “you” is less downtrodden than Geissler was: when a colleague starts leering and invading her personal space, “not being me, you don’t take a step back. You tell him to stop it right away.” Later, though, the author will sometimes abandon “you” to your fate:

While you’re working toward the end of your shift and you’re tired and hungry and you count and count again all the time, and then count what you’ve counted all over again, I’m sitting in a cafe in town with a friend. We’re chatting and drinking white wine spritzers.

Geissler escapes into her freer post-Amazon life, which only serves to underscore how difficult it is for many others to do likewise. No need to slam the door in your face when the door doesn’t lead anywhere.

Photograph © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music & Arts/Art Resource, New York City

Seasonal Associate comes out of a financial constraint that its author eventually managed to use as a literary one. It is, the afterword attests, the indirect result of “the infamous second-and-third-novel problem”—a problem both aesthetic and professional—following the critical success of Geissler’s first book, Rosa. The Australian novelist Helen Garner elegantly conceals the equivalent dilemma in her short second novel, The Children’s Bach (Text Publishing, $16.95), first published in 1984 but only now appearing in the United States, with a new introduction by Ben Lerner. Her debut, Monkey Grip, like Indiana’s Horse Crazy, touched on the difficulties of loving someone who may prefer heroin to you. Here that theme is ever so fleetingly glimpsed again, when tattooed musician Philip slips among “strange beds in houses where a boiling saucepan might as easily contain a syringe as an egg.” Drugs are not this novel’s subject, but the swift and graceful economy of that phrase—which Lerner, too, marvels at—is its most salient characteristic.

An ensemble piece whose thirdperson narration moves gently between the consciousnesses of several interconnected people, the book almost never (perhaps once in 160 pages) shares too much with the reader, leaving its characters a highly unusual degree of autonomy and privacy that only deepens the impression that they live. The cast includes Dexter and Athena, a married couple with two sons, one of them severely disabled; Elizabeth, a long-lost friend of Dexter’s; Elizabeth’s much younger sister Vicki, who after their mother’s death moves into Athena and Dexter’s house; Philip, an on-and-off boyfriend of Elizabeth’s; and Philip’s daughter Poppy. Garner wears her mastery lightly—the novel never draws undue attention to its own modernist tricks. Unfolding, as the title suggests, like a halting piece of music, its effects are subtle and unexpected. People’s judgments of one another are fierce but always shifting, provisional, and, as Lerner notes, the novel itself is “exceptionally nonjudgmental” in a manner that shows up how much implicit guidance often appears in other people’s fiction. You don’t know what Garner’s characters will do, or why (even in the case of those who, like Philip, may appear to be recognizable types), and are not told what meaning to assign to events. The line between fantasy and reality is occasionally allowed to blur for a moment, as it does in the conscious mind—for instance, when the reader can’t tell, because Vicki can’t either, whether she has shoved the disabled boy under the wheels of a truck or only thought of doing so—and even casual literary imagery is often odder than it seems, like the music shop “lumbered with grands,” their lids “propped open as if to catch a breath of air. Their perfect teeth, their glossy flanks, their sumptuous smell caused customers to tiptoe past them.”

Where Geissler makes explicit the contemptuous invasiveness involved in reducing a person to her assigned role, Garner proceeds more obliquely. The forbearance with which she employs the great advantage novelists have—the ability to map interior life—gives her a quality that Indiana, by different means, shares: the capacity to present depths and surfaces at once. Both writers have an unusual talent for exploring those areas of experience that are both partly imagined and intractably real, such as class, or failure, or erotic obsession. Envy the reader who discovers either Garner or Indiana with these early works. She has so many pleasures still to anticipate.