Discussed in this essay:

Why Did I Ever, by Mary Robison. Counterpoint Press. 224 pages. $16.95.

An Amateur’s Guide to Night, by Mary Robison. Counterpoint Press. 144 pages. $16.95.

Tell Me, by Mary Robison. Counterpoint Press. 288 pages. $16.95.

Oh!, by Mary Robison. Counterpoint Press. 240 pages. $16.95.

Subtraction, by Mary Robison. Counterpoint Press. 240 pages. $16.95.

One D.O.A., One on the Way, by Mary Robison. Counterpoint Press. 176 pages. $16.95.

Days, by Mary Robison. Counterpoint Press. 192 pages. $16.95.

Believe Them, by Mary Robison. Counterpoint Press. 160 pages. $16.95.

Money Breton, the protagonist of Mary Robison’s novel Why Did I Ever (2001), lives in Alabama. She has three ex-husbands, two children, and a Ritalin habit. Her daughter, Mev, is addicted to methadone. Her son, Paulie, is under police protection after being violently assaulted, waiting to hear whether he will have to testify against his attacker, and whether he has contracted HIV. Money’s boyfriend, Dix, is a drunk and a moron and very wealthy. Her answering machine indicates that he’s left her twelve messages in eleven minutes. She is a script doctor by trade—currently trying to salvage a film on Bigfoot—an art forger in her spare time, and her cat has gone missing.

The tension is clear, and it’s easy to imagine the narratives that might develop—Paulie tests positive for HIV, and Money, Mev, and Dix kick their respective addictions as they attempt to support him; Money finishes the Bigfoot script, the movie’s a hit, and, flush with success and self-respect, she realizes she deserves better than Dix.

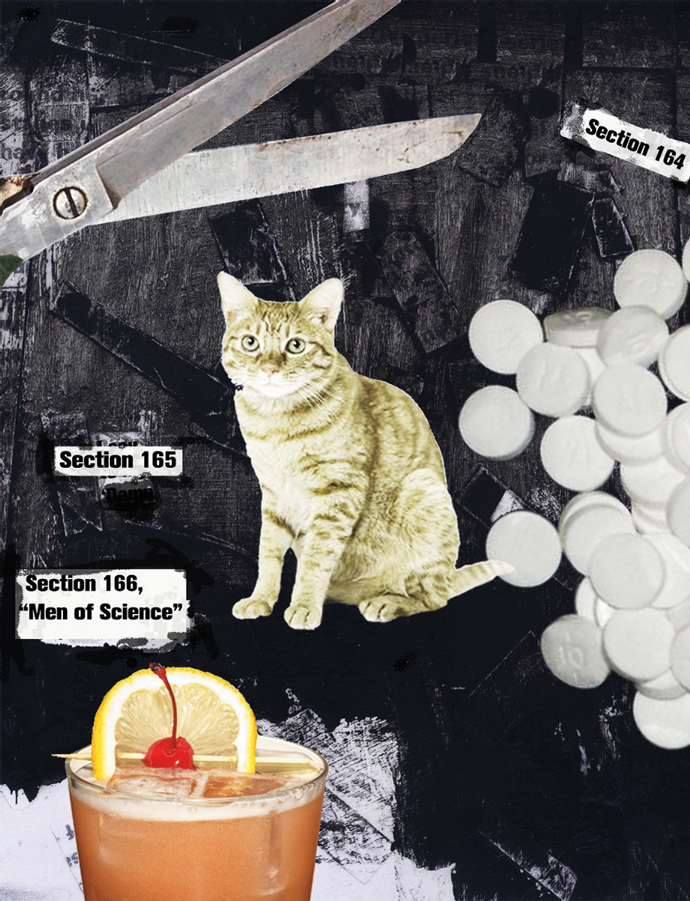

But Robison isn’t interested in cause and effect. The result is a novel, narrated by Money, that proceeds by accretion of seemingly random events, snatches of conversations, idle thoughts and flashes of memory, all described in 536 brief sections, most numbered, a few titled, tongue firmly in cheek. Here is a sample:

164

I can close my eyes and, if I ever want to, go back in time and hear Paulie rehearsing for the dipshit school play, singing in his little sixth grade voice that he had then.

165

I say to myself, “Damn you, damn you, God help you, help you, help.”

Men of Science [166]

“Just getting a little background on you,” says the doctor in Admissions at the nut hospital when I try to check in. “Where did you attend high school?”

By now we know about Paulie and Dix and Mev, and the blurb on the novel’s back cover is happy to fill us in on Money’s marital status, but if the reader wants a consequential chain linking section 164 to 165 to 166, she is encouraged to construct it herself. This is one of the thrills of Why Did I Ever, and of Robison’s fiction generally: she introduces elements like drug addiction, sexual assault, and alcoholism—all of which cry out for explanation and resolution—only to refuse the reader almost any satisfaction. Instead, Robison offers only what happened, and what happened, and what happened.Why Did I Ever does do the reader, and its narrator, a kindness by eventually revealing that Paulie tests negative for HIV. But Dix remains a drunk and Mev doesn’t kick her habit and the Bigfoot script remains in limbo. The cat wanders in and out until, on the novel’s second-to-last page, she is discovered, dead. Even the title—Why Did I Ever, no object, no punctuation—thumbs its nose at follow-through.

Why Did I Ever is Robison’s third novel and one of eight works of her fiction that Counterpoint is in the process of reissuing. All share a lack of interest in plot arcs; an attention to brand names, to apparently insignificant

details, to dialogue at the expense of introspection; an absence of backstory, of context, of predictable consequence, of articulated desire, of, occasionally, sense.

Depending on the reader, Robison’s stylistic choices may be sources of frustration or sources of bliss. One section begins, apropos of nothing, “There’s a lot you can do with paper and scissors, if you have scissors.” The next line: “I don’t, and I don’t really look nice enough to step outside and walk across the gravel courtyard to the office of this motor inn to borrow a pair.” Section 121 reads, in its entirety, “Huh.” Whether a reader calls this revealing, or funny, or a waste of paper will depend in part on whether or not she enjoys a challenge. The sense one has, reading Robison, is of being always a step behind. There is a thrill in running after her (“Huh” refers to what?); one wants to bear her faith out by catching up.

Critics have called Robison’s style—to her own frustration—minimalism. (A refresher, courtesy of John Barth: “The kind of terse, oblique, realistic or hyperrealistic, slightly plotted, extrospective, cool-surfaced fiction associated in the last 5 to 10 years”—Barth is writing in 1986—“with such excellent writers as Frederick Barthelme, Ann Beattie, Raymond Carver, Bobbie Ann Mason, James Robison, Mary Robison and Tobias Wolff.”) Robison prefers to be called a “subtractionist”—“because at least it sounds as if there’s some effort involved.” Minimalism, she said, was “the school no one ever wanted to be in. They’d bring your name up just to kick you.” They kicked her for being, as Barth suggests, too cool—too cold, and too good for anything as square as developed characters or three-act narratives. But this is a fundamental misunderstanding of Robison’s work: she wasn’t trying to be better than anybody. She was only trying to faithfully represent the chaos that is lived experience.

Illustration by Steven Dana

Minimalism provoked critical hostility because its scattershot plots and emotionally enigmatic characters defied traditional attempts at interpretation. Critics couldn’t figure out what these stories meant. Reviewers read Robison’s work as cynical, snide, pointless, and plotless. Take Michiko Kakutani’s tart evaluation of Robison’s third book, the short story collection An Amateur’s Guide to Night. “Miss Robison,” Kakutani writes,

seems so reluctant to impute motive or causality that the stories read like an anthology of random events. In “You Know Charles,” the following sequence occurs: a troubled young man named Allen goes to visit his aunt; he sees a menacing-looking teen-ager standing outside her apartment building; Allen tells his aunt about his problems; she invites the teen-ager in for a visit; she takes photographs of the two young men; she collapses in the bathroom. What is the reader to make of this? That life is ironic? Or that people are unhappy?

There’s nothing factually wrong in Kakutani’s summary, and it’s true that the events of the story are bizarre. But she has omitted a crucial plot point. Allen is visiting his paternal aunt, Mindy, because his father is planning to remarry; Allen, appalled by the idea, seeks Mindy out because he wants to “chat his problems out with someone more mature,” never mind that Mindy is a day-drinker whose only friend may be the thin teenager in a cowboy hat who loiters outside her building. “‘He wants to move her,’” Allen says, of his father’s girlfriend, “‘into the house with us. You can imagine what that’d do to me. I’ve never had to live with a woman. Not since we lost Mom.’ ‘You never lived with your mother, Allen,’” Mindy reminds her nephew. “‘She died in childbirth.’”

Allen has hold of a particular family narrative in which he is central; he is unable to conceive of any other, and is appalled that anyone else might be able to. Focused as he is on his own story, Allen ignores the stories around him: Mindy’s sadness at her failure as a photographer; her loneliness; her alcoholism. Robison’s “anthology of random events” is in fact a selected catalog of the narratives that surround Allen and that, in his self-absorption, he misses. It argues, by way of accumulation and juxtaposition, against the cruelty of the selfish plot-making in which Allen indulges.

We may now finally be in a better position to appreciate Robison’s work. John Barth, in his 1986 essay on minimalism, attributed the style’s popularity in part to “our national hangover from the Vietnam War”; “the national decline in reading and writing skills”; and “the hours we bourgeois now spend with our televisions and video cassette recorders, and in our cars and at the movies.” We might attribute contemporary interest in books like Jenny Offill’s slim, anecdotal Dept. of Speculation, Rachel Cusk’s episodic Outline trilogy, and the stripped-down, deliberately unbeautiful sentences of Nell Zink’s The Wallcreeper, to our ongoing military entanglements in the Middle East, the national decline in reading and writing skills, and the hours we now spend on Twitter. Or perhaps, after decades during which big books have ruled—the year of Why Did I Ever was also the year of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections—we are simply due for what Barth called “a cyclical correction.” Out with the attempt to encompass all; in with the short, the tonally flat, the disjointed, the caustic, the funny.

Though Robison is often compared to Raymond Carver, her style—more grim humor than lyric melancholy—is closer to that of Renata Adler, whose two novels, Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1983) were reissued by New York Review Books Classics in 2013. Robison has Adler’s eye for the telling detail; Adler’s ear for the paradoxical statement, and for the tortured logic of idiomatic language. But in Adler’s novels, the narrator tends to stand apart and above, observing; when she judges, the reader is inclined to trust her. Robison’s characters are sunk hip-deep: their judgments are no more reliable than is the world around them. They may be lying or insane or eccentric: the reader may realize, partway through a scene, that they’ve been walking around with no pants on.

In the opening chapter of Speedboat, Adler’s narrator, a neurotic reporter perpetually on the verge of a nervous breakdown, explains: “A large rat crossed my path last night on Fifty-seventh Street. . . . It was my second rat this week.” And then:

The second rat, of course, may have been the first rat farther uptown, in which case I am either being followed or the rat keeps the same rounds and hours I do. I think sanity, however, is the most profound moral option of our time.

In other words, the world is wild enough to drive you crazy; that’s no excuse. “Two rats, then.” In Robison’s most recent novel, One D.O.A., One on the Way (2009), the narrator visits her sister-in-law at a mental institution. “Overhead here are the branches of a pomegranate tree. A squirrel or whatever just kicked a nut down on me. Or, perhaps that was an accident.” In a world in which logic can no longer be appealed to, because no one can agree on the premises from which to depart, sanity isn’t a moral option; it’s an afterthought.

An afterthought, however, is still a thought. Like Money, the protagonist of One D.O.A. pursues sanity’s level line, if erratically. And her desire to understand the world also means that she is capable of being moved by it. Robison is not a moralist but she is a keen observer, and Oh! (1981), her first novel, is a record of lives lived absent that pursuit of sanity and that capacity to be moved. Oh! centers on the Clevelands, a wealthy Midwestern family: grandfather Cleveland, son Howdy, daughter Maureen, granddaughter Violet, and maid Lola. Over the course of the novel, an engagement ends, a shed is torched, a tornado touches down, and a patriarch absconds, all to no noticeable emotional effect.

Reading Oh!, it’s easy to dismiss the Clevelands. “Are we really as zonked out as Maureen and Howdy?” Katha Pollitt asked in her review. The Clevelands are silly and selfish and stubborn and stupid. What, the reader may ask, do these characters have to do with me?

The answer can be found almost halfway through the novel, when we join Maureen alone in her daughter Violet’s room. The novel’s gears, which until now have been pushing the action along at a manic, sprightly pace, seem to grind to a halt. “She experienced,” Robison writes,

a sudden restless sort of depression. She found herself examining her hands, which were bulky with painted square fingernails and prominent mannish veins. She took a fingernail between her teeth and bit off too much. She stuck the finger in her mouth, caressed the sore place with the end of her tongue. She studied a tack hole in the wall. She called sharply for Violet.

By the time the child comes, the air has gone out of the room. “Something awful was closing down on Maureen.” Nothing specifically prompts this closing down. Maureen, in her solitude, has simply been forced to engage in a rare moment of self-contemplation.

The moments in which Robison allows us to glimpse her characters’ interiority makes clear that they are not merely caricatures, hyperbolic symptoms of ennui from whom the reader can blamelessly distance herself. Their failures as parents and children and humans result not from some essential difference (being too “zonked out”), but from the same combination of circumstance and choice as our own.

Just after Maureen feels “something awful” descend on her, she puts on “a dress with a pattern of red and green confetti.” Violet’s father, a man ten years older, who impregnated Maureen when she was fifteen, has returned and wants to get married. She cannot face him sober; at least she will face him well-dressed. “‘One thing would be deadly,’” Maureen says, “‘and that’s for me to lie down. If I did that, I’d lie there and I’d be lost. I must go outside myself. It’s a trick, but I’ve done it before.’ ‘I know,’” Violet says. For much of the novel, it’s easy to scoff at the Clevelands; here, you feel for Maureen and you fear for her daughter.

In Oh!, wealth means insensitivity to your own problems. In One D.O.A., One on the Way Robison makes clear just how effectively wealth insulates you from everyone else’s, too. One D.O.A. takes place in New Orleans, shortly after Hurricane Katrina. The protagonist, Eve, is a location scout. Her husband, Adam (yes), has hepatitis C, and he’s retreated to his parents’ house, a mansion the storm left untouched.

Adam has a twin, the alcoholic Saunders. Saunders has a wife, Petal. Partway through the novel, Petal has an argument with Saunders in the foyer of a restaurant where the family has been waiting for her. “Petal,” Eve observes, “has ripped her pearl necklace off her throat and is whipping it at Saunders.” A few lines down: “Up there now, Petal’s tearing at her blouse, wrenching off a button, and flinging that at Saunders.” Saunders and Petal and Adam leave; the twins’ parents leave; Eve stays behind, eating lemon crème brûlée. When eventually Eve, too, leaves, she discovers Petal in a car, pointing a gun at Saunders. Eve drives Petal to a mental institution, where Petal commits herself. By now we know that Eve is sleeping with Saunders. “It’s getting light,” Eve narrates, leaving the hospital.

I’m driving on a concrete bridge over a valley of kudzu that blankets the land from here to the horizon. There’s a line of kudzu-covered trees, like a march of great misshapen animals. Seen a different way, what I just conducted was the confinement of my lover’s wife.

One D.O.A. has all the usual hallmarks of Robison’s fiction. There is the deadpan humor and the precision of description. Idioms are manipulated so that their strangeness becomes apparent (not “I can assure you,” but “you are assured”; not “as the case may be,” but “if the case may be”). The narrative, so-called, hiccups along, disjointedly. But, also, between sections detailing Eve’s troubles with her husband, with her lover, with her job, there are lists. There are lists of Eve’s resolutions: “I’m through reading lengthy bits of scripture into the answering machines of my enemies.” There are lists detailing Louisiana gun laws and varieties of gun-holstering options. And, most pointedly, there are lists that sketch the devastation of post-Katrina New Orleans: “An estimated 4,486 New Orleans physicians fled the storm”; “The Journal of the AMA found only 17 psychiatrists returned to the city—that’s 1 per 16,058”; “The suicide rate post-Katrina rose almost 300 percent.”

Like Why Did I Ever, One D.O.A. is carved into short sections, so that numbers in brackets stand between factual bullet points and fictional dialogues, between public life and private life. The introduction of facts represents an evolution in Robison’s fiction, which can otherwise seem insular. But it’s an evolution in keeping with the author’s interest in representing life as it is, rather than life as we wish it were, so that we can understand it better. How often we attempt to cordon off the public so that we can enjoy the private. Inevitably, in the novel as in the world, the former encroaches on the latter.

The narrative impulse, in fiction as in life, is strong. (Arguably stronger, if also more difficult to pursue, when we are drunk; that Robison’s characters so often are seems not coincidental.) It’s the fact of this narrative impulse that makes reading Robison’s fiction so disorienting, in the precise way that lived life is also disorienting. Out of the fragments of experience, one attempts to construct a whole story about a romance, a family, a job, a childhood. Our experience of realist fiction is the experience of receiving and interpreting that whole story, which has been prepared in advance for our consumption. Our experience of Robison’s fiction is of receiving and interpreting, too, but first of constructing. Out of the fragments and incidents and non sequiturs Robison offers, the reader is forced to do what one does in life: build a narrative.

Again and again, reviewers have complained that Robison’s fiction means nothing, that it adds up to nothing; they cry out for insight, for connection, for a glimpse of how her characters “really live.” It’s a kind of capitalist critique: What is this short story, what is this novel, for? But Robison doesn’t subscribe, in her fiction, to the puritan work ethic. One may assume, when a narrative is described as “minimalist,” when its author describes herself as a “subtractionist,” that it’s the superfluous that has been left out—taken out, subtracted. In Robison’s work, it’s the superfluous, the seemingly insignificant to character and reader both, that remains. It is perhaps a depressing fact: how superfluous so much of our lives are; how much we must struggle to make them mean; how impossible that struggle so often seems. At least we can see, thanks to Robison’s obsessive documenting of those plot points furthest from the narrative arc, how foolish we look going through the daily motions of living our lives. At least we can get a few laughs out of the whole pointless endeavor.

Robison’s second novel, Subtraction (1991), is puzzling in relation to her other books. The impression it leaves is softer, baggier, more melancholy and introspective. It’s closer to Joan Didion’s novels, post–Play It As It Lays—the lone woman, stranded in a foreign land, sniffing after traces of her husband, her father—than it is to Renata Adler’s.

The protagonist is Paige, a poet on leave from Harvard, whose husband, Raf, has yet again gone missing. Raf is, we are meant to believe, a charismatic alcoholic, though his charisma—unlike his alcoholism—is very little in evidence. Mostly we see him stumbling around bars, struggling to stand upright. (One thing that does bind the pair: really good sex, something that reviewers at the time, puzzling over Paige’s devotion to Raf, seemed too timid to mention.)

Paige traces Raf to Houston. There she meets Raymond, Raf’s friend, to whom she is immediately attracted. Raf sobers up, then Raf falls off the wagon, taking Raymond, a recovering alcoholic, down with him. Raymond and Paige almost sleep together, but resist the temptation. Raf disappears. Raymond and Paige sleep together. Paige goes chasing, once again, after Raf.

All of these things happen with about the level of causality these clipped summary sentences imply. For a while, it seems possible that Paige and Raymond will end up together. But no: Raymond goes back to Texas, and Paige and Raf reunite. The last lines of the novel, Paige in a car with Raf: “I thought: generic man, perfect man. I thought how even when Raf was dead-still, he had an intensity out of which someone could interpret a world.”

This, especially, troubled reviewers. Raf’s appeal was impossible to suss out. Paige was intelligent; she was employed. She had options! The best one could say of Raf was, to quote Paige’s mother, “He’s an awfully good time.” (We’ll have to take her word for it.) So, then: Why Raf?

In a short section: Paige thinks,

If there was any sense in teaching, it was for someone such as Millicent, in one of my first Harvard workshops. She once situated herself in the Commons Room at Adams House for ten hours, writing hymnal measure, quantitative and syllabic verse. I heard that her friends suggested she move along, to her quarters or to the cafeteria; heard that she swore at them.

The virtue of sustained attention is just that—a virtue. The virtue of Raf is in Paige’s sustained attention to him, no matter his particular appeal or value or complete lack thereof. Their love exists as a fact because Paige has decided it will.

This is the kind of attention Robison pays to life. Specifically the cast-off bits, the butt ends, in which few novelists seem interested. Reviewing Days, her first book, Anatole Broyard wrote,

Mary Robison’s stories seem to me to question our fundamental assumptions about what is relevant in fiction. During most of our waking hours, nothing very exciting occurs, and she appears to be interested in those gray areas.

Perhaps he did not mean this as a compliment; but it is one, and it’s true. The kind of attention Robison pays is the kind that makes the reviewer, the reader, wonder: What does it all—the events of a story; the events of a life—mean? The kind that may make them despair that it means nothing. That is the point—or rather, it is precisely not the point. For Robison, it is the act of attention, and not the object, that matters.