I had finished lunch when I decided to attend the memorial service later that afternoon for Juno Wasserman, who had died the week before, just shy of seventy. Juno had been with my mother at Vassar and Harvard, and I thought I should go at the very least to be able to tell my mother about it, for though they had fallen out I think they still considered each other best friends, and my mother had been in a great self-pity over their lack of resolution.

The service was taking place in a Buddhist meditation studio, in a loft near Union Square. In the tiny hallway leading to the small, slow freight elevator was a crush of people who gave off the smell of coming in from cold air. Their presentness was an absolute contrast with the nullity of death: no looking down, no living on, all electricity gone.

The door to the stairwell was locked, and when a man suddenly came out through it none of us thought fast enough to catch the opening. Along with the waiting crowd of Juno’s people there was another group, of uniformly pretty young women, and when we got on the elevator I noticed they looked like movie temptresses or homecoming queens. Some combination of the mourning, the mismatched crowds, and the tight squeeze made certain that it was a silent ascent, and when my phone began to buzz it was the loudest thing in the elevator, a frantic, petitioning vibration I’d assigned to my mother.

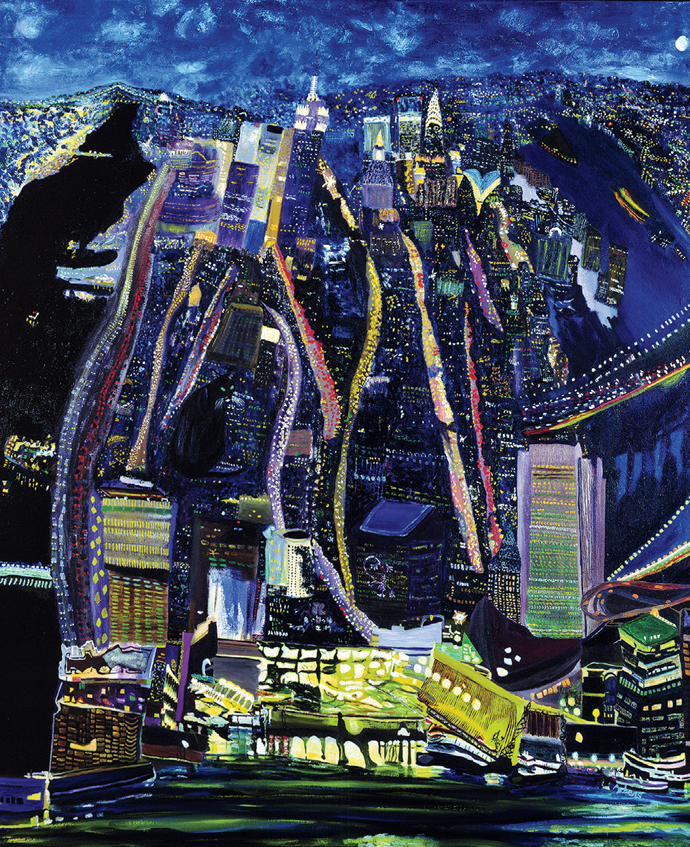

Cat in the Night, by Olive Ayhens. Courtesy the artist

I tried to look around without moving to see if I recognized any of Juno’s crowd, whether they were friends from Vassar or grad school, whom my mother would also have known, or from Buddhist retreats in Thailand, or downtown never-really-made-its who’d had a future for a couple of decades starting in the mid-Sixties, or other folklorists, or weirdos Juno had collected during tale-gathering trips—to Illyria and Patagonia and Formosa and other romantic place names that never were or no longer are the names of countries but still feel like they should be—who later found their way to New York. (There were none I knew, but one of the models I was able to place from the Christmas J.Crew catalog.)

Juno had been born June but, being angry and tireless like the goddess, didn’t want to have such a quiet name. She never legally changed it, and having gone back and forth became consistent only in her early fifties, beyond the point of retraining her friends. Juno always bristled when my mother slipped up, which I suspect she did partly on purpose. Juno in turn called my mother “Debbie,” which had otherwise been shed by grad school.

I sat in a folding chair that turned out to be taken by a wiry-haired man who smelled of camphor, and I found another chair at the back next to Juno’s qigong teacher, a fleshy, extremely alive man whose metaphysical refinement seemed in tension with the vessel.

Juno’s nieces and nephew played a Beethoven string trio. Then came a recording of Juno reading a fairy tale about the Angel of Death and the pious man: one day the Angel of Death comes for him and announces that it is his time. I’d heard her perform it onstage before. On tape her voice sounded thinner, and the different voices she did sounded a little silly without facial expressions to match. “The man said, ‘As God wills it, so I shall comply. But tell me, for pity’s sake, I have three young daughters, and the eldest is a simpleton. Surely God might show mercy and allow me to live only long enough to secure her in marriage.’” (The story went on in the same slightly antiquated translation. The subject might have been on the nose in terms of the memorial, but for Juno to read someone else’s version of a story verbatim was at odds with the usual way she worked.)

The Angel says that “God’s will cannot be broken but that He intends it,” and gives the man a challenge. If he can answer a certain very difficult question, then he is meant to see his daughter wed. The question is: what did the man’s mother place next to him as he slept, on the day he turned two? (I felt a chill of excitement when I heard this line, because I remembered, or at least remembered being told, what my mother handed me in bed the morning of my second birthday: two big gumballs which she’d brought back from America.)

“And thus the Angel of Death departed.

“The man could not remember. At dawn the next day, as he tended his goats, he lamented, ‘O you goats, whosoever can answer Death’s question, let him speak.’ The goats held the man dear, for he had always tended them finely and plucked their burrs and delivered their young. The goats said, ‘The answer you seek is the hyacinth. Now be quick, for Death comes.’”

I picture this Death as some kind of Muslim-flavored Balkan grim reaper who is interchangeable with whatever the relevant Hebrew Bible angel would be. Anyway, here there was a loud pop and a change in the timbre of Juno’s voice, and for the rest of the recording she sounds older, as if two audio tracks from decades apart were spliced together.

The Angel of Death arrives and asks the man the question, and the man answers, and Death praises God and departs. The man weds his simpleton daughter to a simple man, and they are happy and blessed. Then Death comes back, because it’s definitely the man’s time, but now the man would just like to see his homely middle daughter wed. So Death gives him another question: “On the day you turned but one year old, your mother placed in your mouth a gift. What was it?”

The man can’t answer. At dawn the next day, as he tends his horses, he laments, and the horses, who are also fond of the man, tell him that it was a quail egg. Death comes, the man answers correctly, Death praises God and departs, and the man’s middle daughter—“homely but good”—is married to a merchant.

At this, the qigong teacher hummed assent and nodded his head forward over folded arms.

When the wedding is over Death returns, and the man now wants to marry off his third and final daughter, the youngest, who is beautiful. So now the Angel’s question is: “On the day you were born, your mother whispered something in your ear. What was it?”

The Angel departs, and the man can’t remember. At dawn the next day, he is feeding his chickens and he laments, and although the chickens hold him dear, apparently “Chickens are foolish, and only the cock who heralds the call to prayer can speak.”

(I didn’t remember this twist in the story from my previous listening, and my guess about how the man would get out of the trap—by offering a benediction to God’s own Angel—was wrong.)

The Angel of Death arrives and asks. The man can’t answer the question, and he’s shaken that Death has turned up earlier than the other two times. He says only, “I did not know that you would come so soon.” Death praises God and departs.

For these were the words the man’s mother spoke into his ear. The man marries off his beautiful daughter, who is “radiant like the sun itself,” to a prince, and they are happy and blessed.

Rebecca, Juno’s daughter, said some things that took a prescribed form, filled in with personal details. I was thinking that the fairy tale did not quite line up. Juno had only one daughter, not three, and that one was not a simpleton at all, and was neither plain nor pretty but something else.

Juno’s brother who was in attendance said something in passing about another brother, not there. A friend from Buddhist study who had been in regular practice with Juno for some ten years recited a prayer, a translation of a traditional sutra, and standing silently next to her as an “anchor” was this Southern woman who once, in Juno’s back yard in the Village, when I’d moved to New York just after college and for the transitional period been in regular touch with real adults who knew my parents, held forth on Margaret Mitchell and how great she was for not being racist in 1930s Atlanta. Rebecca and the brother stood for the mourner’s kaddish, and, at the end, Rebecca’s husband said they would be having shivah at their home for three days, come on by. Having, not sitting, which I hadn’t heard before and haven’t since.

I moved to America with my mother just after she’d separated from my father. She’d not wanted to lean too heavily on her own mother, who was by then living out in Mamaroneck, so we stayed at Juno’s two-story garden apartment, in a town house on a gated cul-de-sac, off Sixth Avenue, where e. e. cummings once lived. I was six. I watched the WWF in the dim, warm living room for days and days. Juno worked in her study facing onto the garden. When my mother went out, which was often—she said, or I inferred, that she needed to restart her life here—Juno fed me PB&J sandwiches or vegetarian sushi rolls she’d learned to make in Hokkaido. (I wonder now at what extent of my permanence in the United States the legal obligation to send me to school would have kicked in.)

When we left the apartment, Juno and I, something always felt a bit seasick in the universe: a station wagon sat impaling a wall of the diner at Sixth and Waverly, patrons in the restaurant ignoring it. Men were breaking into parked cars in the West 30s outside the Lincoln Tunnel in broad daylight, unchallenged. A platform-level shop in Penn Station sold giant combat knives to commuters.

A rock broke the window over Juno’s desk. The back yard was open only to other residents of her cul-de-sac and of the mews running through the block. She was very upset.

The next day was her teaching gig at Columbia, so she took me uptown and left me with the department secretaries. By the time we got back downtown there was a letter on the door from her landlords in lieu of an eviction notice from the city marshal, stating that she had violated the terms of her lease so they had moved her stuff out, etc. The rock was the landlords’ doing: when Juno had patched the glass pane herself, they claimed, that became a disallowed modification, in breach of the lease. Juno had been there under rent control for more than twenty years, and the owners had made a few lazy gestures throughout her tenancy toward getting her out, but it had been mostly the attrition of neglect. This was a distinct escalation.

Juno took me to the upstairs neighbor and began making lots of phone calls. The neighbor put on the WWF for me. It was the championship that day. (I believe the Ultimate Warrior lost because the ref had been knocked out when Warrior bested Hulk Hogan, who regained control of the match as the ref regained consciousness.)

I was learning to read then and I kept looking at a book of Juno’s, a collection of folktales from a place I’m not sure of, and reading one story in that book. A mouse is married to Mistress Beetle, who dies by falling into her cooking pot when her husband is out of the house, and each new character, upon hearing this news, makes a show of mourning in some way and passes along the accumulated account to a new character, so that at the end it goes like this: The old woman hung a griddle from her neck and went back into the house. “But Auntie, have you gone mad?” said the people in the house when they saw her. “Auntie has put a griddle round her neck,” said she, “Mistress Ant has rent her veil, Grandpa has put a spade through his body, the ibex have dropped a horn each, the hyacinth has shed her blossoms, the spring has turned red as blood, the quail has molted her feathers, the plane has shed its leaves. A curse on the tail of the mouse, the water has killed Mistress Beetle!” The people rose up and pulled the house down and ran away, and they happened then to see the body of Mistress Beetle, and they keened and moaned and buried her body to the sound of tambourines and drums. Each of them went off in his or her own way, and they became wanderers on the face of the earth out of grief for Mistress Beetle.

Juno pretty quickly tracked down the moving company that had been hired to take away and store her belongings. She feared they would be in a terrible state, and she would be proved right. My mother had gone to Poughkeepsie, so Juno had to take me with her. The station wagon entered the throaty hum of the Holland Tunnel and then the sudden bright yawn of New Jersey. We got lost. I was already good at reading maps and following directions, whereas Juno was terrible, and she had the good humor and steady patience to discuss the directions with me. We found the warehouse in what might have been Elizabeth, or Bayonne.

The building was cavernous and sectioned off by sheets of dirty canvas tensioned between weights on the floor and metal joists below the roof. It had a smell of spilt motor oil and adult men that I hadn’t smelled since India. In locating the boss from the phone call, we took further wrong turns before we found a small office that, amid the soaring space, felt like the inside of a refrigerator turned sideways, or like the plush, quiet, Detroit-built boat that had ferried me from JFK to Juno’s weeks earlier. It was full of papers and smoke. The boss was an old man, fifty or seventy, short, white, bald, sour. He said he couldn’t do anything, her possessions still had to be inventoried, and then if she verified ownership she could arrange to pay for them to be moved somewhere. Juno wanted to see paperwork, so he showed her a copy of the same iffy eviction letter. She showed him a copy of her lease and said he knew full well that the eviction wasn’t legal and the letter wasn’t sufficient. She wanted to see her things, so he took her to the loading dock. Her stuff was just piled out there, sitting in the cold late-October early-evening air. Some of it was visibly damaged. Juno’s entitlement to these objects was wearing down the boss’s posture.

There were drawers with family photos, and we found many of Rebecca, who was then around thirteen, living that year with her father in New Haven. There was also a Steinway baby grand, Juno’s father’s from the Thirties, when he played on Broadway and toured the Borscht Belt. Juno volunteered to recite the serial number if anyone wanted to lift the top and check it, though nobody had said it wasn’t hers.

“No way I’m moving that fucking thing again,” said the boss.

From the highways nearby was a swirling like putting your ear to the chest of the world.

He asked whether she played, gesturing to the piano, half curious, half showing his willingness to waste time. Not really, she knew a few things. She was half being modest and half trying to shut down the tangent. But he kept at it. He asked if she knew a particular song.

To tell what happened next is frustrating on two points. First, I don’t know the exact arrangement Juno and the boss came to, but now that Juno is dead let’s assume that he offered, once she had her place back, to do the return move for free, as she wanted, on the condition that she played the song he had named. Second is that nobody, not even Juno when she was alive, could remember what the song was.

When I was in high school visiting colleges out East with my mother, we stayed with Juno. But just a day in, three days before we were set to head up to Boston, Juno told my mother she’d been confused about what dates we were meant to be there, and other houseguests were expected, professional acquaintances Juno knew less well, so we’d have to figure out something else. The offense stayed with my mother, and a few years later, when Juno was to perform her magnum opus at full length—a pre-Islamic Persian epic about a warrioress, spanning eight hours with three intermissions (never before or since staged both in its entirety and in a single day, but Juno had funding and city support in those richest of the Giuliani years)—I came down from New Haven for the show, and my mother had planned to come, she was visiting friends in Princeton but in general the trip was scheduled to coincide with the performance, and I knew, each of the three times the lights came up and I looked around and noted whoever was sitting near me, including a group I later identified as members of Iran’s exiled royals expertly killing time, that she would not be there.

Juno sat on an old dining chair with a cane back, and she tried a few keys, glaring at the boss because something had definitely gone wrong with the tuning. Before she began, he asked her to wait a minute and went inside the warehouse, then came back out with half a dozen men. One of the men brought a hand truck for me to sit on and put a moving blanket around me, the air was getting colder and it was getting dark, and then she played.

The music was confident and the old sodium-vapor lights were like another blanket. Was it a show tune, something from Fiddler on the Roof, My Fair Lady? What would that guy have asked for? Tosca, Springsteen, Sinatra? To me it was just piano. Juno played, and at the end they clapped, the scene was perfect, and for the first time ever I saw the New York skyline lit up in the distance, and for the first time I felt that wonderful sinking rising life-proud world-weary inspired gutted feeling of coming back to the city at night.

Before leaving the service, I wrapped some cookies, one ginger and two chocolate chip, in a napkin. I took the stairs, and when I came out the stairwell door into the narrow hall at the bottom I held it open and explained to some models who were waiting that a lot of people were coming down from the eleventh floor and so it might be a while for the elevator.

I held the door encouragingly, but the models remained uncertain, so I let go of the handle and it, too, hesitated for a moment before closing.

As I walked outside, into the dim winter canyon with the cornices of buildings still catching sunlight up above, I rummaged in my bag for my phone. There were actually three calls from my mother, and I could tell immediately, from the fact that each one had produced a voicemail three minutes long, the maximum possible length, that all of the calls must have been accidental, dialed from her purse or her pocket. I was about to delete them but then it occurred to me that I might listen to what she had recorded, whether she was talking to someone else or moving through the world without speaking.