Discussed in this essay:

The Novel of Ferrara, by Giorgio Bassani. Translated by Jamie McKendrick. W. W. Norton. 744 pages. $39.95.

The Holocaust must be mentioned, but it will not be talked about. It must be mentioned because it is the single most conditioning fact in Giorgio Bassani’s life and in the life of the Jewish community in Ferrara, the northern Italian town where he grew up: in 1943, 183 of Ferrara’s four hundred or so Jews were rounded up and deported to Germany, whence but one returned. It will not be directly talked about because Bassani himself was not among the 183, and apparently had no inclination to describe the horror itself. “Buchenwald, Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Dachau, and so on,” reads a line from one story, and leaves it at that.

Considered one of the finest Italian novelists of the twentieth century, Bassani wrote and published four novels and two collections of stories between 1937 and 1972, later editing and combining them into a huge composite work, The Novel of Ferrara (1974), now published for the first time in English as a single book, with a single translator. Reading it, we contemplate the people of Ferrara over some sixty years, Jews and gentiles, rich and poor, before and after the great convulsions of the Holocaust and the Second World War. Each story is self-contained, but with characters and events that return and call to one another, illuminate one another, so that reading the whole oeuvre together we have the powerful impression of having seen three generations consume their lives, or all too frequently be consumed by violence.

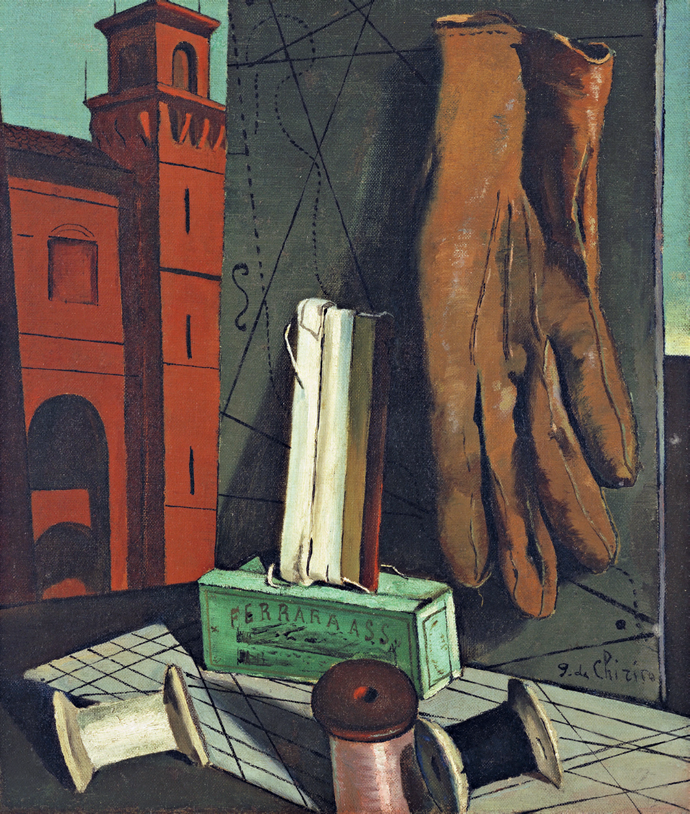

I Progetti Della Ragazza (The Amusements of a Young Girl), 1915, by Giorgio de Chirico. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York City/Scala Archives. Gift of James Thrall Soby

Despite its emotional and intellectual complexity, Bassani’s work is frequently reviewed as if his writing were primarily an analysis and denunciation of Fascism; we mix aesthetic appreciation with complacent political approval, and leave it at that. In reality, his fiction is by no means circumscribed by its focus on a particular historical moment. Nor can his vision be so easily aligned with straightforward liberalism as many commentators would have us believe. True, in Bassani’s masterpiece, The Garden of the Finzi-Continis—a novel about a wealthy Jewish family that chooses to live in genteel seclusion behind the high walls of their villa, ignoring the anti-Semitism growing around them—the whole drama is anchored by the pathos, announced in the opening pages, that the family will be deported to the death camps. Yet the Finzi-Continis remain deeply enigmatic, and their choices open to question. Through them, Bassani explores the relationship between fear and conformity, individually and collectively, what it means to be civilized, and what role art might have in the matter. For readers today, with our own civilization looking increasingly precarious—and the urge to withdraw from it ever more enticing—the allure of these stories is immediate.

Giorgio Bassani was born in 1916 into a moderately wealthy Jewish family. His father would be an early and enthusiastic member of the Fascist Party, formed in 1921, and Giorgio himself, like many Italian intellectuals, would become a member of the GUF, the Gruppi Universitari Fascisti, when he studied literature in the nearby town of Bologna in the mid-Thirties. Here one must remember that the Jewish community in Italy had only been permitted to live outside the ghettos as recently as 1861; given that this liberation was granted soon after Italian unification was achieved, it was understandable that many Jews associated the two events and were eager to be part of the mainstream of the new nation. So successful, in fact, was Italian Jewry at integrating with the wider community that a nonpracticing Jew like Primo Levi could remark that until the late 1930s his Jewishness hardly mattered, was merely a “cheerful anomaly,” and his family felt 95 percent Italian and only 5 percent Jewish. The 1938 Racial Laws—with which Mussolini followed Hitler in discriminating against Jews, essentially excluding them from public life—were thus doubly shocking: Jews had gone trustfully toward the wider community, apparently been accepted, then found themselves inexplicably repulsed.

Rather than the calamity of the death camps, it was this experience of betrayal that profoundly shaped Bassani’s fiction. In his world all involvement in human relationships of any kind is experienced as exposure to risk, the risks of rejection and cruelty. Romantic love is no exception: “something cruel, atrocious, to be spied on from a distance, or to be dreamed of beneath lowered eyelids,” we hear in one early story. And in The Garden of the Finzi-Continis: “Love . . . was something for people who were determined to get the better of each other, a cruel, hard sport . . . with no holds barred . . .”

As a result, many of Bassani’s characters live in constant fear of any involvement in life, hence the pressure to conform, keep one’s head down, or simply, and despite an intense longing for company and affection, to opt out of life completely. The author began his writing career as a poet, and in a late collection, Epitaphs, he wrote,

No, no I won’t bring fresh wood

to the fire let’s leave

the wood already there to burn

itself out little by little

the flames to transform

it little by little to embers

while you and I sit silently

side by side watching

from the deep dark of the room

as even that, at last

goes out.

Sitting beside the author watching a fire blaze—destructive, beautiful, and above all compelling—is largely how it feels reading Bassani’s work. Published to great acclaim in 1956, the five long stories of the opening collection, Within the Walls, lay down the kindling with precision, drawing on Bassani’s intimacy with his hometown and his wartime experiences, dramatizing the yearning of the young, the complacent blindness of the old, and the urgent question: How do I react to threat and calamity—with involvement or flight?

In the first story, set in the Twenties, Lida, abandoned by her Jewish lover, David, after giving birth to their illegitimate child, returns to her mother’s house where she finds “a sense of peace and protection.” The two work together at home as seamstresses, cocooned in tedium. Emotionally, the young woman lives off the passion she had shared with David, but this can never be mentioned to her mother. Both women understand that “their harmony could only . . . be preserved on condition that they avoided any reference to the sole topic on which their closeness depended.”

Complicity in denial is the coal that smolders throughout Bassani’s fiction. It is always what is unsaid that most matters. Not to speak may make a relationship possible, but it also prevents life from flaring up and moving on. Meantime, the unremitting sadness of the story is made beautiful by the silvery evenness of its telling, as if everything had happened an enormously long time ago, and was thus, however painful to its protagonists, somehow bearable and even pleasurable to the reader now.

The second story, “A Stroll Before Dinner,” makes this framing of events in a remote past explicit. Just as Bassani’s central characters are intensely attracted to life but fearful of moving toward it, so the author approaches his material with painstaking indirectness. The narrator finds an old postcard “crammed with details” of a busy street in the Ferrara of decades before: a horsemeat butcher, a schoolboy in danger of being run over by a carriage, a man in a bowler hat pulling down an awning. In the center of the photo “things and people merge together in a . . . luminous dusty haze” so that “a girl of around twenty years of age, at that very moment walking quickly along the left-hand sidewalk” remains quite invisible to “us contemporary spectators.”

Thus Gemma Brondi, a trainee nurse from a working class family, is conjured from a photo where she doesn’t even appear, accompanied by Elia Corcos, a young and gentlemanly Jewish doctor. Despite class and religious divides, the couple are evidently in love. The narrative point of view shifts to Gemma’s older sister, Ausilia, who hides by a bedroom window to spy on the two as they arrive at the girl’s home each evening; their relationship is so exciting, so scandalous.

Will this be a replay, the reader wonders, of Lida’s story, the single mother abandoned by the Jewish lover?

No. When Gemma falls pregnant, Dr. Corcos bites the bullet, enters her home, and asks her “old drunkard” of a father for his daughter’s hand. The Jewish community is appalled that this promising young man should compromise his future by marrying a poor goy. Ausilia, destined for spinsterhood, switches her spying from the lovers to the rumbustious, intimidating Jewish family who gather around the couple.

Elia Corcos, who appears in other sections of The Novel of Ferrara, works hard at his career and is successful despite his “baffling” marriage, until decades later he disappears into the crowd as suddenly as he had earlier emerged from the photograph. In typical fashion, Bassani tucks away the crucial information that the doctor and his son were deported to Germany in an aside at the end of a long parenthesis within a sentence of almost a hundred words. Nothing else is said on the matter.

In the two stories that deal more directly with war experiences, Bassani focuses on diametrically opposed responses to the community’s determination to live in denial. At the very moment, in “A Memorial Tablet in Via Mazzini,” that a decorous and distancing plaque goes up to commemorate the 183 Jews who didn’t come back from Germany, Geo Josz, the sole survivor, does in fact return and simply will not stop talking about the loved ones he has lost, upsetting the townsfolk who are “so fearful they might unexpectedly be called to account.” By contrast, in “A Night in ’43” Pino Barilari, a paralyzed syphilitic confined to a room that overlooks the very wall where eleven citizens were gunned down during the war, will not admit, even under oath, that he saw what everyone knows he must have seen: the killings and the perpetrators.

As always in Bassani’s work, great attention is paid to the function of domestic and public spaces, houses and bedrooms, cafés and clubs. Geo Josz plasters the walls of his room with photos of his dead family—it is a place of witness—and he constantly stands at a high window commanding a view of the main street, as if to remind his fellow citizens he is watching them. Worse, he takes to dressing in his old, death-camp rags to buttonhole people in the smart restaurants and dance halls where they are trying to return to normal life.

The paralyzed Barilari also watches from his window, staring through binoculars at the spot where the atrocity he witnessed took place and shouting vague warnings at whoever passes by. But his room, unlike Geo’s, is a lair of regression and denial, and he sleeps on a child’s bed, surrounded by crossword puzzles and adventure stories.

Geo’s refusal to let the past go—his obsessive bearing witness—becomes intolerable for his fellow citizens, who ban him from all the places where he comes to bother them, until one day, to a great sigh of collective relief, he leaves town forever. If Pino, on the other hand, is able stay on in Ferrara, it is because he keeps his mouth shut. Intriguingly, the closer Bassani comes to describing the massacre this man saw but will not speak of, the more indirect and contorted his narrative and syntax become, as if the prose itself were driven by the antithetical energies of telling and not telling, and the whole construct that is literary Ferrara at once an elaborate refuge from the truth and a bold j’accuse.

It’s quite a challenge for the translator, and Jamie McKendrick’s new version often runs into trouble when the prose gets knotty. Negotiating the complex syntax seems to distract his attention from any number of errors. The punto supremo—last moment—of the lives of the massacred citizens in “A Night in ’43” thus becomes “the lofty vantage point” from which Pino sees them. Of Dr. Corcos we hear that “it was clear that when he’d converted [to Christianity] he’d hardly even considered it.” The Italian gives: “it was clear he wasn’t even thinking of converting.” This is not a minor detail in a story looking at the relationship between Christian and Jewish communities. Geo Josz is described as a “sixteen-year-old survivor” when in fact he is a “self-styled survivor” (sedicente—self-styled—has been mistaken for sedicenne—sixteen-year-old). In fact the figure of Josz was based on a cousin of Bassani’s who was in his mid-twenties at the time, and Josz is clearly no longer an adolescent in this story. At one point a whole paragraph is skipped. Of course one wishes to congratulate the publisher for bringing out all Bassani’s fiction in a single volume; these are works that are stronger together, and fortunately they can still be enjoyed in this translation. Nevertheless, it would be good to see it carefully revised before the next edition.

“Ferrara,” by Luigi Ghirri, from the series Topographie-Iconographie © The Estate of Luigi Ghirri. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Within the Walls was a remarkable debut. But Bassani wasn’t satisfied. If he was to continue as a writer, he now felt, some new ingredient would be required. “I would have to include,” he tells us in the autobiographical reminiscence that closes The Novel of Ferrara, the person who had so far remained “hidden behind the screen of pathos and irony”—himself. So in the short novel that followed, The Gold-Rimmed Spectacles (1958), an anonymous Bassani alter ego narrates in first person the story of Athos Fadigati, who arrived in Ferrara from Venice shortly after the First World War to practice medicine. With his elegant, inoffensive manner, the good doctor “attracted and reassured” people. When, years later, the still-unmarried Fadigati is rumored to be homosexual—though no one will actually pronounce that awful word—it is felt that so long as he remains discreet this will be okay.

But Fadigati is desperate for human contact. Commuting to Bologna, he shares a train compartment with a group of students, anxiously seeking to be part of their company. And one of those students is our narrator, who has trouble knowing how to respond to Fadigati; he is disturbed by his homosexuality and neediness, but also upset when another student repeatedly insults him. Does one get involved or not? We feel the author simply does not know, and the story flares into life.

Madly, Fadigati begins a relationship with the very boy who despises him. In a week of folly on an Adriatic beach, this ambiguous lover first forces the doctor out into the open, then runs off with his money, abandoning him to public disgrace. It’s a terrible betrayal. And all this occurs exactly as the Racial Laws are introduced, so that the doctor’s downfall coincides with the Jewish narrator’s growing sense of vulnerability. The two become uneasy friends, unwilling allies against prejudice and blindness, the narrator being furious with his father who, in pathetic denial, simply won’t accept that Mussolini has turned his back on Jewish Fascists like himself, and that, for a Jew, the easy option of conformity is no longer available.

“From my exile, I would never return,” vows the narrator of The Gold-Rimmed Spectacles in response to the Racial Laws. He is talking of a psychological or spiritual exile, a refusal ever again to look for acceptance from the wider community, as his father so ingenuously had. Certainly Bassani himself, after publishing these stories (which were hardly designed to make him popular in Ferrara, or indeed with its Jewish community) never went back to live in the town and would spend the rest of his life in Rome. But he would often return for a brief visit, or in his mind, not least for the setting of his great masterpiece The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, published in 1962 and in every way more substantial than anything else he wrote.

This time, Bassani’s signature distancing device, in the novel’s opening pages, takes the form of a family visit, years after the war, to some Etruscan tombs. The necropolis is presented as a place of peace and tranquility, “so well defended, adorned, privileged,” a place of “perpetual repose” where you feel “nothing could ever change.” It is here, we are told, that the author finally decided to write about the Finzi-Contini family, who were never to lie in any cemetery.

All the familiar Bassani themes and polarities—to engage or not engage, the yearning for love and defense of privacy, fear and courage—are reshuffled and deployed for maximum effect. The unnamed narrator, again a Bassani alter ego, tells of his youthful fascination for the children of the wealthy Finzi-Continis, who, quite unlike his own family, lived in “absurd isolation” in a large house and huge garden just inside the town’s imposing walls. The only time these homeschooled children, Alberto and Micòl, can be regularly seen is at synagogue, where they sit directly behind the narrator, whose father has to constantly forbid him to turn and stare. At the end of the service, as the children are gathered under their fathers’ prayer shawls, they peep at each other through chinks in the fabric, each yearning to be admitted to the other’s different world; the daughter, Micòl, in particular, is “strangely inviting.”

But like any object of desire, she is also dangerous. Years later, miserable after failing an exam, the narrator is riding his bike when he comes across the now teenage Micòl perched on the high wall of her family’s garden. She invites him to climb up. Excited, he is held back by a fear of heights, fear of Micòl, and fear his new bicycle will be stolen. Why can’t he come in through the gate? Mocking, she climbs down and shows him where he can hide the bicycle in an underground chamber in the town wall opposite the garden, a place that looks “a bit like the Etruscan monterozzi” which is to say, tombs. Advancing alone into the dark, the boy spends so long looking for a safe place for his bike, while simultaneously fantasizing an erotic encounter with Micòl, that when he returns from the tomb she is gone, at which he feels he has escaped “the greatest danger a boy of my age . . . might ever meet.”

When narrator and reader finally enter the garden of the elusive Finzi-Continis, what they find is at once richly imagined, intriguing, entirely credible, and above all impossible to pin down. Does the family, in its remove from society, represent the apex of civilization, or a pathetic aberration? However many times one comes back to the book, the puzzle remains unsolved, both for us and, one feels, for Bassani too.

Owning thousands of acres of land farmed by thousands of workers—something they themselves would never be so tasteless as to mention—the Finzi-Continis are astonishingly self-sufficient. “They had everything”: well-stocked libraries of books in many languages, all sorts of recreations, a tennis court, every kind of food and drink (they do not restrict themselves to kosher meats). The house comes complete with an elevator. Proud and dutiful goy servants make domestic life as easy as it can be. A telephone extension in each bedroom is a “safeguard” for “personal liberty.” The vast garden includes trees and plants from all over the world.

Who would ever want to leave such a place? Indeed, the Finzi-Continis seldom do. Each is a collector in his or her own way. Alberto has his records, his stereo, and obsessively controls background music and ambient lighting; Micòl fills her bedroom with scores of làttimi, tiny Venetian glass ornaments. She studies the supremely hermetic Emily Dickinson. Their father, Professor Ermanno, has collected all the inscriptions on the tombs of the Venice Lido’s old Jewish cemetery where he met his wife. They possess the world in safety. Isn’t this what civilization is about? Isn’t it admirable that the professor has refused Fascist Party membership?

But can one live a full life without mixing with others, without addressing the political realities that threaten to destroy you? In so many ways the garden of the Finzi-Continis resembles a well-kept cemetery. Nothing can happen here. Speaking a bizarre family dialect to each other, brother and sister never seem to talk about anything that matters. Old furnishings decorously decay. When the Racial Laws are introduced and Fer-

rara’s Jews are expelled from the local tennis club, the Finzi-Continis seem glad of the chance to invite their coreligionists to play on their own court. Some of the young people in Bassani’s previous stories turn up.

Playing tennis deep into an Indian summer as Europe hovers on the brink of war, the narrator falls in love with Micòl, who gently flirts yet equally gently repels him. The two sit in the dark of the old coach house in an antique horse-drawn carriage and, to the reader’s dismay, fail to kiss. Micòl flees to her university studies in Venice, but encourages her would-be boyfriend to keep visiting her lonely brother, while her affable father suggests he use the family library for his own studies. So, for months, the narrator enjoys a highly cultured environment where the rising tide of anti-Semitism is ignored or simply accepted as a confirmation that the only thing one can do is withdraw. There is no talk of resistance, or escape, or a response of any kind. Yet as the plot thickens, the tennis games drag on, and the Finzi-Continis become ever more amiable, the reader senses that this is a terrible trap, a Gothic nightmare. We want our lovesick boy to get his girl, and at the same time we fear for his future if he does. With great stealth, the novel has drawn us into the conflicted state of mind that is its subject: Should we go toward life or defend ourselves from it? Is civilization “safe” if it involves denying ugly reality?

Brothels appear frequently, if marginally, in Bassani’s fiction. They are where young men go when desperate for contact but unable to approach a real object of desire. Tennis likewise provides a way of engaging without real exposure or risk. Nor is any Bassani protagonist without a bicycle, which offers an illusion of freedom and reduces the danger of unpleasant encounters in the street. It’s hard to think of a writer more adept at the embarrassed conversation where something needs to be said but never is, or more capable of creating moments of catharsis when two people do at last communicate. More frequently, though, Bassani’s characters have to make do with the voyeuristic gaze, fascinated but excluded, as when the Garden’s narrator rides his bike slowly past lovers making out and feels like a “strange . . . ghost, full both of life and death.”

All these elements would turn up again in the author’s later works. Accused, absurdly, in the mid-Sixties by a group of experimental writers (Umberto Eco among them) of being a conventional sentimentalist, Bassani changed style drastically in The Heron (1968), assuming a third-person stance to deliver a driving inner monologue and an existential drama that unfolds in a single day. A Jewish landowner, Edgardo, who has never come to terms with the postwar world—alienated from wife, family, and workers—decides to take up hunting again, booking a scout to meet him in a nearby town and take him to a blind in the marshes to shoot duck. Bodily needs and unexpected developments force Edgardo into a series of unwanted encounters and phone conversations with old acquaintances and relatives, all of whom seem as enviably at home in this new world as they were under Fascism. Ensconced in the blind with his shotgun, concealed and watching, he finds himself unable to shoot, while his guide, hidden nearby, brings down bird after bird, including a fine heron; the creature is inedible, the guide admits, but will look very good stuffed. Edgardo’s immediate identification with the dead heron, useless as anything but a memento of past life, triggers a determination to end his own existence that paradoxically cheers him up immensely. The novel, Bassani later commented, served to get its author out of a long depression.

In The Smell of Hay, the closing work in this collection, we are watching a last glow of dying embers. The dangers of intense, youthful engagement with life behind him, or only savored in memory, Bassani now feels free to emerge from the protection of fiction and reflect more openly on his life as a writer and the lives of the people he knew, many of them recognizably the characters in his novels. The strongest piece here tells of a friend who passes from a determinedly dissolute youth to a willfully conventional marriage—neither of which really convinces his friends—until one day, with life absolutely secure in a well-appointed home complete with a caring wife and delightful children, he simply disappears, never to be heard of again. It seems that for all its attractions the bourgeois life at the core of our Western civilization can only come at the price of denial—of sexual desire, a will to cruelty, a constant yearning for change—and this, in the long run, is hard to sustain.

Married in 1943 to a girl he met at the Ferrara tennis club, bringing up a family of two children, Bassani himself chose neither to disappear nor to live in denial. During the war he carried messages for the resistance and survived a brief period in prison. Later he would be a founding member and president of Italia Nostra, an organization that seeks to protect Italy’s culture and landscape. In this regard, he was very much his father’s son. At home, as we learn from his daughter Paola’s memoir, he would discuss his mistresses with his long-suffering wife, complaining of them as people from whom he needed protection. Certainly that would have brought fuel to the fire. Eventually leaving his marriage, Bassani spent the last twenty years of his life and a long slide into Alzheimer’s with the American academic Portia Prebys, whom his daughter, in a gesture worthy of a character in her father’s books, contrives never to mention in her biography.

Bassani’s life, in the end, revolved around the same preoccupations as the novels, with the same passions and the same uncertainties, which, no doubt, is why The Novel of Ferrara is so captivating. It is easy, after its demise, to denounce Nazism, far more difficult to know how to behave from day to day.