Discussed in this essay:

Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly, by Joshua Rivkin. Melville House. 496 pages. $32.

Cy Twombly: Fifty Days at Iliam, edited by Carlos Basualdo. Yale University Press. 168 pages. $35.

I first saw Cy Twombly’s paintings as a teenager, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where Fifty Days at Iliam, his ten-painting cycle inspired by the Iliad, occupies a large gallery all its own. I remember, on that visit, being thrilled and scandalized by Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés, which involves looking through a crack in the wall at a disturbingly lifelike naked woman sprawled on the ground, and feeling respectful toward, if secretly baffled by, the works of Jackson Pollock and the other stalwarts of Abstract Expressionism.

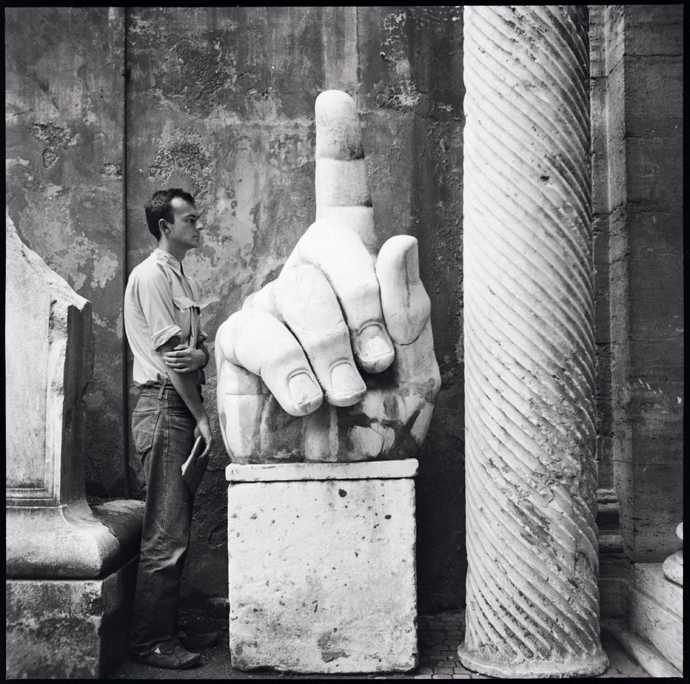

“Cy + Relics—Rome,” 1952, by Robert Rauschenberg © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/VAGA/Artists Rights Society, New York City. From Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly, published in 2018 by Melville House

But the Twomblys, large canvases filled with the furiously scrawled names of Greek and Trojan heroes and colorful, violent spirals of scribble evoking mass bloodshed, provoked a visceral revulsion. Partly abstract, partly figurative, and filled with mysterious lines of text, they seemed to be distant relations of the collection’s other works of twentieth-century art, but also to contain the un-pedigreed, otherworldly rawness of art brut. There was a blood-soaked, clawlike figure with vengeance scrawled above it, titled The Vengeance of Achilles; a jumble of shapes, swirls, and semi-legible names called Ilians in Battle; battalions of flying penises proliferated throughout. The paintings’ monumental size and prominent placement in the museum seemed specifically intended to taunt a viewer expecting to find a serious theme treated seriously.

After years of skepticism, I have come to see in Twombly’s best paintings a poignant dramatization of the artist’s dilemma, the canvases giving host to competing impulses toward both aesthetic mastery and ugly blunt force. His paintings provide something of the dark joy one feels walking through an ornate, ruined church, or listening to a drunk, brilliant conversationalist just before she becomes completely incoherent. But that initial revulsion I felt isn’t an uncommon first reaction to Twombly’s art, and it points to the mystery surrounding his enduring appeal. Since his death in 2011, Twombly, who rose to prominence in the midst and immediate aftermath of the Abstract Expressionist generation, has become ever more firmly ensconced in the art-history canon. Like his slightly older contemporary Philip Guston, whose break with abstraction in the late Sixties cast him into a reputational no-man’s-land, Twombly’s refusal to clearly and consistently inhabit an artistic lineage has made his work particularly au courant in a “post-everything” art landscape, in which no one school or style dominates the markets or museums. His combining of abstraction with figuration and text was a major influence on Jean-Michel Basquiat and other Neo-Expressionist painters of the 1980s, and his anarchic spirit can be felt in subsequent waves of artists, such as Dana Schutz, whose painting of Emmett Till aroused bitter controversy, and Laura Owens, both of whom combine abstraction and recognizable subjects in visceral, unexpected ways. Twombly has had retrospectives at the Whitney, MoMA, and the Pompidou, and his mature works routinely sell for eight-figure sums. Yet even today, his seemingly infantile technique leaves him vulnerable to charges of overhyping or charlatanism.

The confusion surrounding his work stems in part from the tension between the lineage claimed through his subjects—no less than the foundational works of Western civilization—and the reality of what one finds on his canvases or pedestals—furious, inscrutable crashes of tormented squiggles, illegible or obscured handwriting, un-monumental monuments. But this tension is also one of the main sources of energy in Twombly’s art, forcing viewers to grapple with the contradictions of paintings that declare themselves to be multiple seemingly irreconcilable things at once. The extensive secondary literature interpreting Twombly gives a sense of the varied reactions his work has inspired—his paintings are best understood as graffiti, or should certainly not be seen as such; the poetic titles and lines embedded in the pieces are essential to unlocking the meaning of the work, or they can be set aside as footnotes; his paintings are representative, however obscurely, of people and things, or, as the art historian Gottfried Boehm claims, they represent “nothing that might be visible in external reality.”

Twombly himself was, even given the low bar set by painters, unusually reticent about his intentions. “I’m not an abstractionist completely,” the artist said in a characteristically ambiguous illumination of his work. “There has to be a history behind the thought.” In the few interviews he ever gave, Twombly, an intensely private man, often came close to endorsing the reading of his work as that of a restless naïf whose comments fall somewhere between poker-faced jokes and complete sincerity. In front of his painting Apollo, he remarked to the director of the Menil Collection, as if in explanation, “Rachel and I loved to go dancing at the Apollo Theater in Harlem.” Edmund White wrote in a profile of the artist, “You can’t trust everything Twombly says. When I asked him what his parents did, he said they were Sicilian ceramicists, and that they’d sold their pots in Ogunquit, Maine. When I asked him how many paintings would be in his MoMA show, he said, without a blink, ‘Forty thousand.’”

He is an artist in desperate need of a full-length biography, and Joshua Rivkin’s Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly is the first attempt. Rivkin was partially foiled in his work by the reluctance of the Twombly Foundation to allow access to the artist’s archive, as well as to important associates and materials, a refusal that inevitably comes across in the book as overprotective and self-defeating. But even in ideal conditions, Rivkin’s book was unlikely to be a definitive traditional biography. A poet and creative writing professor, Rivkin often filters his understanding of Twombly’s art and life through his own experience of grappling with it, focusing as much on the tantalizing ambiguities presented by the artist’s work as on the available facts. Given his relative lack of access to primary source material (and the gaurded interviews to which important figures such as Twombly’s son, Alessandro, did submit), another writer might have simply written a short, impressionistic appreciation or settled for a pithy portrait of the artist as an enigma sealed off by his posthumous handlers, like Janet Malcolm’s book about the battles over Sylvia Plath’s legacy, The Silent Woman. Instead, Rivkin combines these modes with that of a full-dress chronicle, recounting Twombly’s life with the biographical information he was able to dig up (most significantly from the archives of Twombly’s friend and sometime lover Robert Rauschenberg). Interspersed throughout, meanwhile, are close readings of the work, well-researched accounts of important exhibitions and milestones, the narrative of the author’s own engagement with the important sites of Twombly’s life, and his quixotic attempts to wrangle information from the living members of Twombly’s small circle.

Though Rivkin is at times left to throw up his hands and admit that he won’t be getting to the bottom of this or that episode or painting, his book is nevertheless a valuable synthesis of what’s been said and written about Twombly, and the author’s lyrical analyses of Twombly’s paintings are both lovely and insightful. “Twombly’s Green Paintings,” Rivkin writes,

swirls of dark jade and white, with occasional flashes of blue, are lush, and yet, in their nearly monochrome palette, austere. A rich and fecund shade, Hooker’s green—a color one critic described as “cooked spinach”—is washed over with white, like waves.

He sees in these paintings Twombly’s debts to “Monet and Turner and Poussin” and “to nature—the shifting patterns of water and grasses, the fish nipping at the surface of the pond.”

Rivkin first fell under Twombly’s spell while working at the Menil Collection in Houston, where he guided schoolchildren through the galleries and led them in writing exercises based on the paintings. There is an entire pavilion dedicated to Twombly’s work there, including his massive, three-panel Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), a mysterious, Turneresque landscape Twombly worked on for two decades and completed when he was in his sixties. Rivkin often copied down the best examples of student work at the museum but preserved very few poems or stories inspired by Twombly, perhaps, he muses, because the children “never wrote well about his work.” The poem he does reproduce, though, by a third-grader named Ajdin, captures the violent, obscurely prophetic nature (cassandra is the largest and most prominent name in his House of Priam) of Twombly’s paintings:

He had to tell the people but it was too late and all the people

were screaming for their lives because the tornado was there.

When the tornado went away all the people died. But the man

who knew the tornado was coming did not die.

In his “kids say the darndest things” way, the student illuminates one of the central debates about Twombly’s work: What does he know? And more importantly, how seriously is one to take the results of his magpie approach to scholarly allusion? Critics easily become lost in the labyrinth of quotations that Twombly draws on in his paintings. To take one significant example, Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor (the title itself substituting “shores” for the “plains” of the translation Twombly is quoting) contains, some more visible than others, an Archilochus fragment, lines from Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Tenth Duino Elegy,” George Seferis’s “Three Secret Poems” and “Automobile,” and Richard Howard’s “1889: Alassio.” Rivkin himself is of many minds about quotation in Twombly’s paintings. Though he dutifully catalogues the references in many of Twombly’s works, he registers doubts about what can be gained from reading obsessively into the artist’s choice of source material. But he does find value in a broad analysis of the themes that Twombly is drawn to, writing, “It’s hard to miss the same-sex desire in the texts and writers Twombly borrows. Gay writers, some open and others closeted, but all writing of desire, its pleasures and complications, its consequences, its longings, its losses.” That so many of these quotations are obscured or semi-legible gives weight to Rivkin’s central understanding of Twombly as an artist hiding in plain sight, his work saying, for those who care to look closely enough, what the artist and the posthumous keepers of his legacy would prefer not to discuss.

He was born Edwin Parker Twombly in 1928 in Lexington, Virginia, a university town that is also home to the graves of both Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. “Cy” was a nickname passed down from his father, also named Edwin Parker, himself nicknamed for the Hall of Fame pitcher Cy Young because of his (brief, undistinguished) stint as a pitcher for the Chicago White Sox. Twombly the younger, though tall and lean, “showed no enthusiasm for organized athletics.” Though he gained fame while (and, early on, jingoistic opprobrium for) living abroad, he returned periodically to Lexington over the course of his life, completing a number of his significant late paintings in a storefront studio downtown that Rivkin visited.*

Twombly’s talent for painting was encouraged from a young age by his mother, who arranged for him to take lessons in his teenage years with Pierre Daura, a Spanish-born war exile. After graduating from Lexington High, he bounced through short stretches at the Museum School in Boston, the art program at Washington and Lee, and the Art Students League in New York. At the last of these, he fatefully met Robert Rauschenberg, the artist whose “combines,” including Bed, from 1955, in which he painted on a quilt and sheets, played a pivotal role in the shift from Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art. Twombly and Rauschenberg embarked on a romantic relationship and a (nearly) lifelong friendship.

In 1951, Rauschenberg encouraged Twombly to follow him to the legendary Black Mountain College, in North Carolina, where he met the Abstract Expressionist painters Robert Motherwell and Franz Kline, as well as the college’s charismatic leader, the poet Charles Olson, whose passion for hieroglyphs and Mayan culture were an inspiration to Twombly. In a 1952 application for a travel grant, Twombly wrote, echoing Olson, “For myself, the past is the source (for all art is vitally contemporary). I’m drawn to the primitive, the ritual and fetish elements, to the symmetrical plastic order (peculiarly basic to both primitive and classic concepts, so relating the two).” Olson felt a strong kinship with the young artist, writing to Robert Creeley about

the pleasure, of talking to a boy as open & sure as this Twombly, abt line, just the goddamned wonderful pleasure of form, when one can talk to another who has the feeling for it—and christ, who has?

The Black Mountain period and the years immediately following, in which Twombly traveled for the first time to Italy, where he would spend extended periods for the rest of his life, and then to North Africa, with Rauschenberg, are among the most pored-over of his long working life, both because of their irresistible romantic appeal and because they are perhaps the best documented. One can see in these materials the beginnings of Twombly’s transformation from a fairly typical product of his milieu—his early paintings are heavily indebted to the totemic figures of Motherwell and Kline—to the sui generis artist he became. Photographs taken by Rauschenberg in Rome—a series of Twombly advancing toward (or away from) the camera on the steps of a fourteenth-century church in Ara Coeli, another of Twombly surreally contemplating the enormous stone hand broken off from a statue of Constantine—capture, in their wry juxtaposition of the personal with the ancient, the first breaths of Twombly’s playful engagement with antiquity and the Renaissance.

Rauschenberg left Twombly behind after only a couple of weeks to work a construction job in Casablanca, later claiming that he was driven away, “furious” and in need of money, by Twombly’s obsessive antique collecting. However, they soon made up. Twombly joined him there, and they traveled through Morocco together, collecting experiences and artifacts and meeting up with, among others, Paul Bowles. In 1953, he and Rauschenberg exhibited work in New York inspired by their travels. The reviews were mostly hostile, a preview of the uphill battle that Twombly’s art would face in the years to come. James Fitzsimmons’s review in Arts & Architecture is a veritable bingo card of criticisms that one can find in assessments of Twombly’s work over his career:

Large, streaked expanses of white with straggling black lines scrawled across them, they resemble graffiti, or the drawings of pre-kindergarten children. . . . Presumably the feeling-content of this art is ugliness: shrillness, conflict, cruelty. . . . The artist is clearly a sensitive man and this is what he finds in the world. Does he have to express it clumsily?

It seems that he did, or at least chose to do so for the duration of his working life. The question about the “childlike” nature of Twombly’s work never really goes away. Of his mid-period Green Paintings, Rivkin notes that the “method might be childlike, finger-painting, though the result is anything but childish.” The poet and critic Craig Raine writes of his late Coronation of Sesostris cycle, from 2000, “They are characteristically Twombly exercises in sophisticated infantilism of deception, coupled with a kind of Alzheimer’s calligraphy, which is uncertain—taking a line for a few hesitant, childish steps, trembly, wobbly, twombly steps.”

Twombly’s first major painting cycle on classical themes, Nine Discourses on Commodus, shown at the Leo Castelli Gallery in the spring of 1964, was another critical disaster, but it represented a significant shift in his art, a dynamic and mature amalgamation of history painting and Abstract Expressionism that was to become his signature. Usually understood as a gloss on the violent reign of the mad Roman emperor Commodus, the paintings chart the dynamic relationship between two violent, opposing eddies of color, which variously resemble clouds, bloodstains, and explosions as they come together and apart across a landscape of grids and other seemingly arbitrary geometric and mathematical symbols. Like all of Twombly’s best work, the paintings seem to pulse with desperation, conveying urgent, garbled news. Rivkin notes that they were completed in the month following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and it is hard not to see an acknowledgment of that epochal event in the viscous, bloodlike smears on the canvas. But, as Rivkin is also wise to point out, Twombly had been alluding to historical murders and assassinations for years before this, in works with titles such as The Ides of March, Death of Giuliano de Medici, and Pompey, all created in 1962. (As Twombly once noted, “All my things, every one of them, show a certain agitation.”) Donald Judd, in a brief, dismissive review of the original exhibition, concluded, “There isn’t anything to these paintings.” Given the density of visual information, this seems an especially ungenerous assessment. Rivkin mischievously flips Judd’s put-down to mean “there isn’t any one thing to these paintings” and determines that “the sequence of nine canvases attempts to capture the tension between control and rage, between containment and dissolution.”

These qualities are also central to the Fifty Days at Iliam sequence, completed in 1978 and dissected from a multitude of angles in Cy Twombly: Fifty Days at Iliam, a new book commemorating its nearly three decades as, in the words of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s curator of contemporary art, Carlos Basualdo, a “towering, enrapturing, and somewhat enigmatic presence.” Twombly was inspired in his work by Alexander Pope’s notoriously free 1715 translation of the Iliad, “an English version of the epic poem,” Emily Greenwood writes in a thorough essay about Pope’s influence on Twombly, “that is itself a highly self-conscious response to the tradition of interpreting, translating, and reimagining Homer.” She also draws parallels between Twombly’s idiosyncratic methods of appropriation (his deliberate departures from the traditional spellings and narrative elements of the text) and those of contemporary translators and interpreters of Homer such as Christopher Logue, whose War Music includes giant type to signify a god’s appearance on the battlefield, and Alice Oswald’s Memorial, which strips the poem’s text down to a stark catalogue of the dead and the methods by which they met their demise. “In common with Logue’s and Oswald’s translations,” Greenwood writes,

Twombly’s version of the Iliad can helpfully be viewed in terms of structural translation: a mode of engagement, homage, and creative reinvention that pares away detail to reveal a striking impression of the energy of the poem and the lineaments of its plot.

Such comparisons suggest that, through his irreverent transformations of classical material, Twombly conceived of the ancient past as a vivid, living thing, something to be bent and reconfigured at will rather than admired from a distance. Achaeans in Battle sends gunlike phalluses swarming into word-and-paint-stained chaos, hurtling cartoonlike out of the frame. Shades of Achilles, Patroclus, and Hector unites the heroes as pulsating clouds, radiating regret in the afterlife. Nicola Del Roscio, Twombly’s longtime companion and current president of the Cy Twombly Foundation, in his essay in the new catalogue, goes so far as to say that Twombly’s “paintings of battles are always those of a convinced anti-war person who was against any kind of violence,” but it seems a leap to attribute such a firm perspective to his cryptic work. Twombly’s seeming fixation on the brutality of war—Fifty Days has sometimes also been seen as a commentary on the pointless slaughter of the Vietnam War—does not in itself serve as a condemnation, as many a proponent of war’s necessity will readily acknowledge its horrors. Twombly’s paintings, like Goya’s mysterious late works, draw their power from the violence they depict. They do not clearly condone or condemn the violence; in their color palette and gnarled composition, they enact it.

In the years following the poorly received Commodus exhibition, Twombly’s work gained enough acceptance within the art world to warrant a major retrospective at the Whitney, in 1979. While the initial reviews from critics were characteristically mixed (Twombly, exaggerating, said that it went over “about as well as a turd in a punch bowl”), the show, according to the art critic Brooks Adams, “played a catalytic role at a moment between the end of Conceptual art and the coalescence of Neo-Expression” and “prepared the ground for the appearance of Julian Schnabel, Anselm Kiefer, Francesco Clemente and Sandro Chia in New York a year or two later.” With the shift in taste to this new generation of figurative artists operating under the sign of Twombly, his own work, Adams noted wryly, “must have seemed like the ne plus ultra of Old Masterish cachet” for contemporary art collectors, and the prices fetched for his work at auction rose steadily. Both his reputation and valuations were given a further boost when Twombly made the move from the most influential gallerist of the previous generation, Leo Castelli, to the paradigmatic representative of the globalized contemporary art world, Larry Gagosian. He took one last public thrashing—as the poster child for the nonsensical gyrations of the art market in a 60 Minutes segment titled “Yes . . . But Is It Art?”—before being fully canonized in a career-spanning MoMA retrospective in 1994.

Rivkin is often at his best navigating the complex territory of reputation formation, carefully tracking the reception of the MoMA show (aided by the rare profiles to which Twombly submitted in order to promote it) and the concurrent exhibition of Say Goodbye, Catullus, first shown in New York as An Untitled Painting. Rivkin quotes extensively from Peter Schjeldahl’s ambivalent contribution to Artforum’s issue marking the MoMA retrospective. Schjeldahl writes perceptively about Twombly’s painting—“His work is as much a form of behavior as a product of craft. It is restless, with the discontent of a dog that turns and turns, unable to feel just right about the place it has chosen to lie down”—but he is bothered by his elevation by the market, at the expense of other worthy, if sometimes more superficially difficult, artists, to the position of “boss abstract painter after the New York School.” This problem—the market as final arbiter of taste—hasn’t exactly gone away, and the exorbitant prices fetched by Twombly (and his stylistic disciple Basquiat) too often stand as the self-evident final word on the quality and importance of the art itself. Rivkin shows the publicity machine at work, with critics, gallerists, and museums all doing their part to create the sense of a “moment” around the MoMA retrospective. He also records Twombly’s ambivalence about participating in this process. “I’m just not interested in myself that way,” he said to Dodie Kazanjian in Vogue, in response to a question about his personal life. “I was brought up to think you don’t talk about yourself. I hate all this.” And yet, reluctantly or not, he did it.

Rivkin spends a significant amount of time noting the discomfiting elision and erasure of Twombly’s sexuality in the many catalogues and chronologies of his work. Though married, from 1959 until the end of his life, to the Italian heiress Luisa Tatiana Franchetti, who funded his bohemian-aristocratic lifestyle until the public caught up to his work, Twombly’s romantic relationship with Nicola Del Roscio, and his reliance on Del Roscio for everything from travel itineraries to serving as the sole reporter on his acts of creation in future catalogues and retrospectives, comes across as the most significant of his life. Presumably in keeping with Twombly’s wishes, Del Roscio’s role in the official narrative remains opaque, his name, for example, absent from the biographical wall tags of a recent major retrospective, even as his personal reminiscences fill the catalogue for the exhibition. But his physical presence at Twombly’s side is constant, even if the ultimate effect on his work is unknowable, at least for now.

Rauschenberg’s role in Twombly’s life, though shorter in duration, is clearer, thanks in large part to Rauschenberg’s meticulous documentation. “Flowers for Bob, a pencil-drawn bouquet in a vase, is inscribed by Twombly ‘Happy birthday dear heart . . . a rose just budding,’” Rivkin notes. “Another birthday drawing, more than two decades later, Some Flowers for Bob 1982, offers a fist of wine-dark reds and purple petals, oil pastels on paper.” Amid all the wrangling and postulating over Twombly’s difficult, mirage-like art, it’s lovely to find these straightforward tokens of affection, proof that the gnomic artist was capable of making art that speaks directly to the emotions. In their humanity, they assure admirers of Twombly’s work that the connection one feels to it is, despite the prices and skepticism and decades of mythmaking, not mere projection.