Discussed in this essay:

The Nocilla Trilogy: Nocilla Dream, Nocilla Experience, Nocilla Lab, by Agustín Fernández Mallo. Translated from the Spanish by Thomas Bunstead. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 560 pages. $30.

The May 18, 2004, edition of the New York Times carried an article by Charlie LeDuff, under the headline middle gate journal; on loneliest road, a unique tree thrives. The article begins with a solitary man hitchhiking from San Francisco on the transcontinental US Route 50, which runs 260 miles through the Nevada desert, from Carson City to Ely, “a whorehouse at each end and not much company in between.” After a few paragraphs, LeDuff shifts his attention to a local curiosity: about halfway through the desert, near the tiny town of Middle Gate, a collection of cottonwood trees has put down roots despite the arid conditions, and passing travelers have covered one of them with thousands of shoes—“snorkeling flippers, tennis shoes, work boots, flip-flops, high heels, pumps, baby booties.” LeDuff speaks with locals who explain how the tradition of tossing footwear on the tree began two decades earlier and offer their own philosophical gloss on the phenomenon:

The shoes are like some kind of letter or photograph or stain, the locals explain, some proof that something happened here, that there are other souls traveling on the road of loneliness.

Soon after the article appeared, a Spanish physicist and poet, Agustín Fernández Mallo, transformed it into a short, strange novel called Nocilla Dream. As this title suggests, the book is less an adaptation of the article than an adaptation of the dream you might have if reading the article had been the last thing you did before turning off the lights. (Nocilla is a chocolate and hazelnut spread, the off-brand Spanish equivalent of Nutella, which gives its name to a punk song that Fernández Mallo happened to hear on the same day he read “Middle Gate Journal.”) Fernández Mallo’s book begins with a solitary hitchhiker from San Francisco on the “loneliest highway in North America,” and it ends with the same Shoe Tree origin story reported to LeDuff. Several locals quoted in the article appear as characters, with notable alterations. (A line from a bartender named Sherry is put almost verbatim in the mouth of a prostitute, also named Sherry.) Around this core, new story lines proliferate—a professional wall climber and his son drive Route 50 on their way to a competition; a woman in China conducts an online affair with the climber while her pedophile husband commits rape in front of reality TV cameras; an Argentinean staked out in a Las Vegas hotel room obsesses over Borges’s parable about a map as large as the territory it represents.

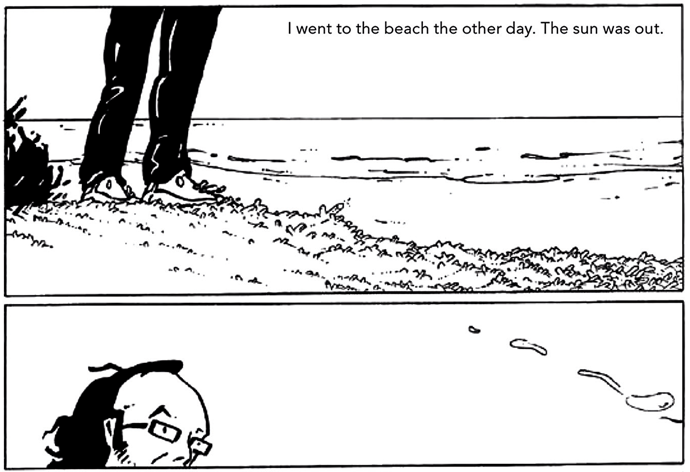

Illustration by Steven Little

Nocilla Dream contains 113 chapters, many just a few lines, almost none longer than two pages. Some are short quotes from books on computer science, information theory, encryption, and cinematography. One chapter recounts another Times article from the period, about the stunt sport of “extreme ironing.” Several others examine the real-life phenomenon of micro-nations, in which radical libertarians and performance artists have declared sovereignty over various geographical and conceptual spaces. Knowingly fatuous philosophizing abounds: “The nomad makes a hearth around an idea,” begins a half-page chapter in which Michael Landon sits on the set of Highway to Heaven, reminiscing about Little House on the Prairie and contemplating mortality. Having faked his own death in Bolivia, Che Guevara travels to newly liberalized Vietnam, where he browses Che T-shirts before being unceremoniously run over by a motorcycle. There are, by my count, at least forty named characters introduced in the space of 175 pages. The whole thing is somewhat like the Shoe Tree—a network of branches, extending from a tenuously rooted foundation, onto which a confounding variety of crap has been tossed.

Soon after finishing Nocilla Dream, Fernández Mallo wrote a follow-up, Nocilla Experience. The second book carries over none of the plotlines from the first, but shares its form. This time there are 112 short chapters. A pair of young boys smuggle radioactive material from Ukraine to Kazakhstan by swallowing metal pills containing the isotopes and walking through underground pipelines. Every night they shit out the pills, wipe them down, and swallow them again. Immediately above them, in the Russian city of Ulan Erge—which sounds like a name out of Borges but is a real place—stands

a huge glass dome . . . intended to house all the things a person can imagine as long as the things a person imagines are related to Parchis, an adaptation of the Indian board game Pachisi, the ancestor of Ludo.

In Brooklyn Heights, reservations must be made months in advance for a restaurant that serves “furtive Polaroids of the customers taken through a hole in the kitchen wall, then fried in egg batter.” Julio Cortázar makes several appearances in which he attempts to explain the methods behind his groundbreaking novel Hopscotch, which offers readers ninety-nine “expendable” chapters that can be inserted between the book’s essential ones. Excerpts from real interviews conducted by the Spanish rock journalist Pablo Gil and variations on a single quote from Apocalypse Now make up between them about one tenth of the book. One chapter consists entirely of an excerpt from David Brooks’s review of a Malcolm Gladwell book, which is either the funniest or the stupidest literary gesture ever committed to paper.

The last volume in the trilogy, Nocilla Lab, is marginally more conventional than its predecessors. After a long first section that unfolds in a single sixty-page sentence, the drastically short chapters return, but they tell a single, relatively straightforward story. Given the autobiographical current of contemporary fiction, the first two volumes are notable for the complete absence of any authorial personality, but in Lab the project takes the seemingly inevitable self-referential turn, recounting in the first person the story of a Spanish writer named Agustín Fernández Mallo who is engaged in a vague but all-encompassing “project.”

Still, the events that transpire are too weird to qualify the work as autofiction. Early in the novel, the narrator buys a Portuguese translation of Paul Auster’s The Music of Chance, in which a man who comes into a surprise inheritance abandons his life to drive back and forth across the United States, and Auster’s book becomes a kind of totem throughout the narrative. Though Fernández Mallo the character insists he has never read the author’s work before, Nocilla Lab feels very much like an existential road-trip novel in the Auster style. While on vacation in the Mediterranean, Fernández Mallo and his girlfriend find themselves at a prison that has been converted into a hotel. The proprietor stays in his room all day, surviving on government ecotourism subsidies rather than serving his guests. Gradually, Fernández Mallo takes over the role of running the hotel, only to discover that the proprietor, also named Agustín Fernández Mallo, is busy at work on the same grand project that the narrator has been neglecting. In the novel’s last pages, which devolve first into journal fragments and then into a comic strip, the narrator, no longer sure of his own identity, swims out to an oil rig, where he sits down for a coffee with Enrique Vila-Matas—a Spanish writer long famous for including real-life friends (Paul Auster among them) in his novels.

The Nocilla books were translated into English and released individually in the United Kingdom by Fitzcarraldo Editions, and they appear now in the United States in a tricked-out box set meant to signal “publishing event.” Like some other notable multivolume literary projects that have recently made their way to our shores—Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels and Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle—they arrive with some extraliterary mystique in tow. In Ferrante’s case, this had to do with the author’s anonymity; in Knausgaard’s, something like the opposite. Here the legend concerns the project’s publication history.

“Nocilla Dream was the first Spanish book ever to go viral,” the trilogy’s translator, Thomas Bunstead, explains in his introduction. Put out by a small independent press, the book provoked an enormous reaction in Spain, becoming “the defining literary event of 2006.” A larger publisher promptly bought the next two books, which turned Fernández Mallo into “the most discussed Spanish author of the decade to follow.” When a group of young writers held a conference in 2007 to discuss “the conservatism they felt to be suffocating their national literature,” they were promptly dubbed the Nocilla Generation, a name that most of them seem to have embraced. (Fernández Mallo did not attend the conference.) Bunstead quotes one member of the cohort who calls Nocilla Dream “a shot to the heart of traditional novelistic representation” and another who says the book “radically changed my idea of what literature was.”

The most internationally prominent contemporary Spanish writers and, presumably, those against whom the Nocilla Generation is reacting, were born in the Fifties or early Sixties and came of age while Franco still had a firm grip on power. These writers—Javier Marías, Antonio Muñoz Molina, Javier Cercas—are deeply preoccupied with the historical catastrophes of twentieth-century Europe and Spain’s ambiguous role in them. They are all self-consciously literary and, while all impressive prose stylists, they tend toward ponderousness.1 Fernández Mallo was born in 1967, eight years before Franco’s death, and he came of age during the 1980s, which were, Bunstead writes, “a little like the sixties, seventies, and eighties in other Western countries all rolled into one.” He is, in his own way, self-consciously literary—the Nocilla project contains countless references to writers and artists—but he is allergic to the self-seriousness of his elders. He is not interested in working through the moral compromises made during the Franco years. In fact, he displays little interest in history or politics at all. Or, for that matter, in Spain: the Nocilla books spend far more time in the United States and Central Asia than in Europe. This thoroughly global view is one of the things that most clearly mark the books as contemporary.

Still, American readers may be a bit surprised by the radical claims being made on the trilogy’s behalf. Most of its distinctive features—absurdism, fragmentation, the appropriation of other writers’ work, the collision of high and low culture, the inclusion of photographs and other non-literary media—have been staples of avant-garde literature for at least fifty years and in some cases more than a hundred. Author’s notes at the end of each volume explain that the trilogy “responds to the transfer of certain aspects of post-poetical poetics into the sphere of fiction.” When I read this, I thought of the opening of Roberto Bolaño’s Savage Detectives: “I have been cordially invited to join the visceral realists. I accepted, of course . . . I’m not really sure what visceral realism is.” Fernández Mallo has written an as-yet-untranslated essay outlining exactly what he means by the term “post-poetical,” but since this essay did not appear until after the trilogy was completed, the Spanish-language readers who made the Nocilla project such a success presumably had no more idea what transfers might be at play than will the American readers arriving at the trilogy now.

Some critics have suggested that Fernández Mallo’s methods, particularly the way he structures his narratives as networks of thematic relationships rather than linear stories, are a way of grappling with digital media. It’s clear that online research played a large role in the books’ composition, and occasionally Fernández Mallo provides URLs for some of his sources,2 but he isn’t especially interested in life online as a subject. Most of his characters live resolutely analog existences, sitting in the sun outside Southwestern brothels or raising pigs in Azerbaijan. There are references to the internet, but fewer than you’d find in a contemporary work of conventional realism. The prevailing technologies are tape decks and Polaroids. The great high-culture touchstones of the trilogy are Borges and Cortázar, two Argentines who died in the 1980s and did their best work decades before that. The “low culture” counterparts in this high-low mix are punk and zine aesthetics that are themselves more than thirty years old. “Nocilla ¡Que Merindilla!,” the song that inspired the project’s title, was recorded in 1982. The Music of Chance was published in 1990.

As is often the case with certain kinds of experimental literature, the books often give off the vague hint that some kind of preconceived operating principle is at play, along with the stronger hint that knowing the details of that principle would not add all that much to the reading experience. The essential ingredient seems to be speed. The same author’s notes that identify the post-poetical transfer specify the time frames in which the volumes were written. Dream: “between June 11 and September 10, 2004”; Experience: “between December 2004 and March 2005”; Lab: “summer of 2005.”

This is an impressive pace, in its way, but these days the competition is fierce. Fernández Mallo’s work arrives in the United States as part of a procession of books that have foregrounded the velocity of their composition. Knausgaard’s three-thousand page My Struggle was written at a rate of up to twenty pages a day. His four follow-up books, the Seasons Quartet, were composed as a series of daily journal entries and published without revision. The Scottish writer Ali Smith is now three volumes into her own Seasonal Quartet, books that have been written in a matter of weeks and published almost immediately after their completion. The first of them, Autumn, is set in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, and it was in bookstores just four months after the referendum took place. Olivia Laing’s Crudo was written in seven weeks, during which Laing gave her Twitter followers more or less daily updates on her progress. Where once it was a mark of high-art seriousness to work on a book for two decades, now the real cred comes from getting it done in two months.

Detail of a comic strip from Nocilla Lab, by Agustín Fernández Mallo. Courtesy the author and Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Ever since Flaubert established the tireless quest for le mot juste as the signature feature of literary work, writers have rebelled against this conception of their art. Some have seen their task as psychic spelunking, deep exploratory work that can only be undermined by literary preciousness. The most prominent proponents of this school have probably been the Beats. Ginsburg’s “first thought, best thought,” Kerouac’s Benzedrine-fueled marathon typewriter sessions, and Burroughs’s automatic writing were all efforts to serve the reader a naked lunch of reality sandwiches. Others have argued that a writer’s real materials are not words, sentences, and the perfectly placed period, but other people, life, the world out there. In this view, fetishizing the tools of the trade is a sterile, even masturbatory, approach.

Knausgaard falls squarely in the former camp. Like the Beats, he is chasing dangerous emotional truths, and he fears that taking the time to polish his material may occasion a loss of nerve—self-censorship by way of revision. Both Smith and Laing are at least partly driven by the challenge of making the usually slow-footed form of the novel keep pace with contemporary life. In a world where we’re all obsessed by last night’s presidential tweets, it no longer feels tenable to set a novel in a vague present tense located at some point in the three- to five-year span between a novel’s conception and its publication.

None of this applies in Fernández Mallo’s case. There is a complete absence of psychologizing in the trilogy, even when the author appears as a character. The Fernández Mallo of this fiction is quite obviously a literary construct rather than a tortured human being working through difficult truths. No angry uncles will be suing him for Nestbeschmutzung. And despite their reliance on newspaper articles for inspiration, the books contain nothing that grounds them particularly in the second half of 2004 and the first half of 2005. One plotline in Experience concerns the son of an American soldier and an Iraqi civilian, living in Baghdad, but it might have taken place at almost any time over the past fifteen years.

So what is Fernández Mallo after? In his introduction, Bunstead astutely notes that Fernández Mallo’s overarching theme is the human effort to impose order on chaos. He has a particular fascination with projects, especially artistic projects, that seek to control nature. Thus his interest in micro-nations, cartography, artists who “go to a field, paint a white line across it, and call the work Sculpture.” A character in Dream flies a prop plane over Carson City, attempting to create a taxonomy of urban sprawl. The Polaroid-snapping chef in Experience hopes one day to “cook the horizon.” Fernández Mallo seems to find these efforts noble but ultimately pointless. The speed with which the hotel in Lab—which began as a prison, the ultimate symbol of modern efforts at social control—deteriorates in the absence of human oversight suggests the power of entropy to tear apart any human endeavor.

The suspicion that the center cannot hold is itself hardly new, of course. Nor is the sense that the artist’s task is, as Beckett put it, to find a form that accommodates the mess. What distinguishes Fernández Mallo from many artists who have worked over these themes is that he is on the side of the mess. Given his own experience with the joyful anarchy of post-Franco Spain, it is perhaps no wonder that Fernández Mallo takes a dim view of the imposition of order. But he doesn’t treat chaos as a grand social metaphor or a particular feature of our overmediated modern life. In keeping with his day job, he sees it instead as an enduring fact about physical reality. He wants to show us this fact—and speed is one way of doing that.

The strategy comes with a price. These books read as though they were written quickly. The prose is not bad, exactly—there are none of the outright barbarisms that appear throughout Knausgaard’s work—but it is strikingly flat. There is no notable shift in quality when we move from a passage written by Fernández Mallo to an academic text or the extemporaneous musings of Eddie Vedder. Presumably, this is intentional; Bunstead commends the “general neutrality of [Fernández Mallo’s] prose style,” which is an accurate if perhaps generous way of putting matters.

Fairly obvious errors are sprinkled throughout. The Brooklyn Bridge is referred to as the bridge “that connects Manhattan to the continent.” The hitchhiker on Route 50 has somehow managed to serve for some years in the Army while never before leaving San Francisco. (The hitchhiker in the article was a “military brat” who moved constantly.) These errors seem to be part of a wider aesthetic strategy. At one point, Fernández Mallo recounts an anecdote about Thelonious Monk, who reportedly walked offstage after one show, frustrated that he had “made all the wrong mistakes.” Live improvisation clearly holds more allure for Fernández Mallo than studio-session perfectionism. But erecting a theoretical justification for a novel’s weaknesses does not make them go away. The best writers can make their works feel like a grand improvisation while still maintaining complete control.

One member of the Nocilla Generation has compared Fernández Mallo’s method to “literary channel-hopping.” Though not intended as such, the remark strikes me as a poignant reminder of the dangers to the writer of trying to keep pace with technological change. It probably did not occur to many people at the time these books first appeared in Spain that within a decade channel hopping—in the sense of skipping around live TV, choosing between various synchronously broadcast programs, trying to avoid the commercials—would be consigned to the past.

But there is another problem with the metaphor. If a novel reproduces the experience of channel hopping, it can only be channel hopping of the very worst kind: the kind where someone else is working the remote. You read one page and then the next, the order decided by author, not reader. Even a book like Hopscotch encourages readers to skip around according to a plan devised by Cortázar himself. Though it might go to great lengths to represent nonlinearity, the novel is an ineluctably linear form. Efforts to give the reader real control—such as various experiments in hypertext, or B. S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates, which was published unbound, in a box—have had limited success.3

This may explain why, almost thirty years after the World Wide Web was conceived, and roughly twenty since the internet became a defining feature of life in the developed world, some people are still waiting for the definitive “internet novel,” a book that doesn’t just integrate digital life into its story but truly captures the experience of living so much of our lives online. It’s not at all clear to me what such a novel would look like, how it would be possible, or whether its existence is even desirable.

So much of life online is not just chaotic but enervating and, increasingly, dull. There is a long-standing argument regarding how far mimetic art ought to go in representing the sometimes dispiriting realities of modern life. Would a book that hopes to honestly capture the strange combination of outrage and boredom, urgency and meaninglessness that defines online life need, in turn, to be outrageous and boring and urgent and meaningless? Fernández Mallo goes further than most in this direction. It’s true, I often thought while reading these books, the internet is like this: we jump from absurdity to absurdity, never staying anywhere long enough to feel too deeply about it; we have the gnawing suspicion that the whole thing could stand a good fact-checking; meanwhile, some guy is quoting David Brooks quoting Malcolm Gladwell, and we’re not entirely sure whether he’s trying to be funny or profound.

Of course I am being a little unfair here, to Fernández Mallo and the internet both. Life online is not all trivial or tedious, but the greatest things about the internet—the way it makes a seemingly limitless array of cultural resources available to us, for instance, or the way it connects people across great distances in real time—are the hardest things for a novel to depict. You can write about having access to all of this, but you cannot actually reproduce the experience of that access. At best, you can throw enough random things at the reader to suggest limitlessness. But even then, we are left with the “remote” problem: the wonderful and terrible thing about the internet is the feeling that we are the ones in control—that we’re doing it to ourselves. A novel, on the other hand, is the expression of a unified individual vision, one to which the reader willingly submits.

At some level, Fernández Mallo knows all this. The irony of his monument to disorder is that it’s at its best precisely when it is most coherent—in the first volume, when the image of the Shoe Tree provides a structure for all the motley parts, and in the third volume, when Fernández Mallo recounts a unified story that is pregnant with meaning. It is in these pages that we see a strange and original sensibility at work—one that combines a deep commitment to the possibilities of art with a gonzo spirit and a complete absence of pretention—and get the chance to spend some intimate time in its company. Such connections are what literature does best. It would be a shame if too many novelists gave them up for the aesthetics of velocity.