The story begins, as so many do, with a journey. In this case, it’s a seemingly simple one: a young girl, cloaked in red, must carry a basket of food through the woods to her bedridden grandmother. Along the way, she meets a duplicitous wolf who persuades her to dawdle: Notice the robins, he says; Laze in the sun, breathe in the hyacinth and bluebells; Wouldn’t your grandmother like a fresh bouquet? Meanwhile, he hastens to her grandmother’s cottage, where he swallows the old woman whole, slips into her bed, and waits for his final course.

Little Red Riding Hood, 1885, print after a drawing by Frédéric Théodore Lix From Les Contes de Perrault, published by Garnier Frères © akg-images

“Little Red Riding Hood”—with its striding plot, its memorable characters, and its rich symbolism—has inspired ceaseless adaptations. Since the seventeenth century, writers have expanded, revised, and modernized the beloved fairy tale thousands of times. Literary scholars, anthropologists, and folklorists have devoted reams of text to analyzing the long-lived story, interpreting it as an allegory of puberty and sexual awakening, a parable about spiritual rebirth, a metaphor for nature’s cycles (night swallowing day, day bursting forth again), and a cautionary tale about kidnapping, pedophilia, and rape. Artists have retold the story in just about every medium: television, film, theater, pop music, graphic novels, video games. Anne Sexton wrote a poem about “a shy budkin / in a red red hood” and a huntsman who rescues her with “a kind of caesarian section.” In Roald Dahl’s version, she “whips a pistol from her knickers,” shoots the wolf in the head, and wears his fur as a coat. The 1996 movie Freeway recasts the wolf as a serial killer and Little Red Riding Hood as a teenage runaway. Liza Minnelli starred in a Christmas special modeled on the fable. Both Walt Disney and Tex Avery—the cartoonist and director who helped popularize Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Elmer Fudd—made animated versions with decidedly different themes.

It is generally assumed, especially in the West, that the many variations of “Little Red Riding Hood” are based on a single definitive European folktale: the one with a wolf in a nightgown and a famous exchange about big eyes and teeth. In truth, this familiar narrative is just one member of a remarkably ancient and cosmopolitan family of myths and stories. If you were raised in Italy, you may recall the girl eating the food in the basket herself and replacing it with donkey dung, only to be gobbled up by her vengeful werewolf relative. Perhaps you know the tale of the baby goats who are devoured by a devious wolf but rescued when their mother cuts open the beast’s torso and fills it with rocks instead. In Africa, there’s a story about a girl freed from the stomach of an ogre who impersonated her brother. And in Asia, there’s a tale of siblings who escape from a tiger posing as their grandmother.

As a child in Dubai, the anthropologist Jamie Tehrani grew up with the what-big-teeth-you-have version of “Little Red Riding Hood.” Decades later, while studying tribal culture in rural Iran, Tehrani noticed that numerous local folktales were curiously similar to the ones he had heard as a kid. There was a story about a beautiful woman cursed to fall into a deep sleep and the brave warrior who woke her up—an Iranian “Sleeping Beauty”—and another about a boy attacked by a wolf while traveling to visit a relative. These ringing echoes might have been coincidence. But it was also possible, Tehrani realized, that the tales were related—that they shared ancestry. This is the same dilemma evolutionary biologists confront when they find two very similar species in different parts of the world. Narrative doppelgängers might have descended from a common ancestor, like tigers and snow leopards, or independently converged on similar features, like bats and birds.

In many ways, stories are uncannily similar to living organisms. They seem to have their own interests. They compel us to share them and, once told, they begin to grow and change, often becoming longer and more elaborate. They compete with one another for our attention—for the opportunity to reach as many minds as possible. They find each other, intermingle, and multiply.

Since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, scientists have repeatedly proposed that the laws of biological evolution apply not just to bird and beast but also to creatures of the mind. Perhaps most famously, in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, the English evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the word meme to describe a “unit of cultural transmission” analogous to a biological gene. Memes, he wrote, could be ideas, tunes, or styles of clothing—essentially any product of human intellect. Moreover, they were not just metaphorically alive but technically living things.

As early as 1909, folklorists started comparing the evolution of stories and organisms, envisioning Linnaean taxonomies and evolutionary trees, or phylogenies, for myths and tales. Generations of scholars compiled and sorted folktales from around the world, resulting in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index: a compendium of more than two thousand folktales, each with a unique identifying number, grouped first by specific shared motifs—“Supernatural Tasks”; “Man Kills Ogre”; “God Rewards and Punishes”—and then into larger tribes, such as “Animal Tales” and “Tales of Magic.” But until recently, researchers did not have the advantage of sophisticated statistical techniques or advanced computer software.

Tehrani wondered whether he could sort out the genealogy of all the “Little Red Riding Hood” variants—Aarne–Thompson–Uther type 333—with something similar to modern phylogenetics, the DNA-informed statistical method biologists use to construct evolutionary trees of living things. Genetics revolutionized evolutionary biology and taxonomy. Unlike their predecessors in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, modern biologists no longer depend primarily on morphology and anatomy—on appearances—to establish evolutionary relationships between organisms. They can also compare their DNA, which maintains a record of familial mergers and divisions over great spans of time. As different species evolve, they accumulate genetic mutations at a more or less steady rate. In general, the more similar the genomes of two species—the more that certain key sequences of As, Ts, Cs, and Gs match—the more recently they split from a common ancestor. Using this general approach, Tehrani and a few other researchers pioneered a new kind of “phylogenetics” specifically for folktales and myths. The gist of their method is to reduce stories to their most fundamental structural elements—the narrative analogue to genes, sometimes called mythemes—and statistically analyze the number of discrepancies between those elements to determine ancestral relationships.

Tehrani gathered fifty-eight variants of “Little Red Riding Hood” from thirty-three cultures and broke them down into seventy-two essential narrative elements, such as type of protagonist (single child or siblings, male or female), tricks used by the villain, whether the protagonist is devoured, whether the protagonist escapes, and so on. Then he fed the data into computer programs that use statistics to build phylogenetic trees.

The results provided a new resolution to decades of debate regarding the origins of “Little Red Riding Hood.” An ancient story preserved in oral traditions in rural France, Austria, and northern Italy was the archetype for the classic folktale familiar to most Westerners. On a separate limb of the tree, the story of the goats descended from an Aesopian tale dated to 400 ad. Those two narrative threads merged in Asia, along with other local tales, sometime in the seventeenth century to form “Tiger Grandmother.”

Inspired, Tehrani and his colleague Sara Silva used similar methods on 275 “Tales of Magic” from fifty populations in India and Europe. Scholars have long pondered the true origins of such stories, many of which only achieved widespread literary fame between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, following publications by folklorists such as Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm. Were they really sourced from European peasants, as claimed? And if they were genuine folktales passed down through the generations, just how old were they? This time the results were even more revealing. Tehrani and Silva discovered that some had existed for far longer than previously known. “Beauty and the Beast” and “Rumpelstiltskin,” for example, were not just a few hundred years old, as some scholars had proposed—they were more than 2,500 years old.

Another folktale, known as “The Smith and the Devil,” was astonishingly ancient. Multiple iterations—which vary greatly but typically involve a blacksmith outwitting a demon—have appeared throughout history across Europe and Asia, from India to Scandinavia, and occasionally in Africa and North America as well. “The Smith and the Devil” became part of Appalachian folklore, and it’s a likely forerunner of the legend of Faust. Tehrani and Silva’s research suggests that not only are these geographically disparate stories directly related—as opposed to evolving independently—but their common ancestor emerged around five thousand years ago, during the Bronze Age.

“Most stories probably don’t survive that long,” says Tehrani. “But when you find a story shared by populations that speak closely related languages, and the variants follow a treelike model of descent, I think coincidence or convergence is an incredibly unlikely explanation. I have young children myself, and I read them bedtime stories, just as parents have done for hundreds of generations. To think that some of these stories are so old that they are older than the language I’m using to tell them—I find something deeply compelling about that.”

The story of storytelling began so long ago that its opening lines have dissolved into the mists of deep time. The best we can do is loosely piece together a first chapter. We know that by 1.5 million years ago early humans were crafting remarkably symmetrical hand axes, hunting cooperatively, and possibly controlling fire. Such skills would have required careful observation and mimicry, step-by-step instruction, and an ability to hold a long series of events in one’s mind—an incipient form of plot. At least one hundred thousand years ago, and possibly much earlier, humans were drawing, painting, making jewelry, and ceremonially burying the dead. And by forty thousand years ago, humans were creating the type of complex, imaginative, and densely populated murals found on the chalky canvases of ancient caves: art that reveals creatures no longer content to simply experience the world but who felt compelled to record and re-imagine it. Over the past few hundred thousand years, the human character gradually changed. We became consummate storytellers.

A miniature of the crow, the turtle, the rat, and the gazelle, characters from Kalila wa Dimna, a collection of Arabic fables, thirteenth century © PVDE/Bridgeman Images

The name Polyphemus comes from the Greek poly, meaning many, and pheme, meaning speech, reputation, or fame. Polyphemus, then, means one much spoken of, someone of great repute. In 1857, Wilhelm Grimm (of the Brothers Grimm) published an essay comparing ten legends and myths similar to the tale of Polyphemus, the man-eating, sheepherding cyclops who traps Odysseus and his crew inside a cave in the Odyssey. Each of these ten stories pitted a hero against a malevolent one-eyed giant. Grimm believed they all branched off from a single ur-mythos.

Recent research suggests that Grimm was right. In the past six years, Julien d’Huy, a scholar at the Institut des Mondes Africains, has performed a series of phylogenetic analyses on fifty-six variants of the Polyphemus tale. Based on his results, d’Huy thinks that the essential plot common to all these narratives—a hunter encounters a monster guarding a group of animals, gets trapped with the monster, and manages to escape by clinging to the animals—emerged more than twenty thousand years ago during the Paleolithic period. Later, the myth traveled through Africa and then across Europe, in parallel with the spread of livestock farming, morphing and speciating all the while. To d’Huy, the myth represents an ancient belief in a “master of animals” and the desire to free those animals from his or her control—perhaps a personification of chance or a metaphor for the struggle of early humans against the vagaries of weather, disease, and hunting. In a way, the many iterations and adaptations of the tale of Polyphemus are their own woolly disguise, so thickly layered on such an ancient story that we can only glimpse its original form.

One of the oldest and most prevalent motifs in storytelling—and a testament to the creative power of stories themselves—is the transformation of the inanimate into the living, often at the hands of a talented artist. In Greek mythology, Hephaestus, the god of crafts, creates a giant bronze automaton to protect Europa, the mother of King Minos of Crete. In Jewish folklore, golems are anthropomorphic figures animated by magic, often depicted as large troll-like creatures made from clay or mud. In a tale from China, a magician gives a young peasant boy an enchanted paintbrush that brings whatever he paints to life. And the Italian writer Carlo Collodi created the character of Pinocchio, a wooden puppet that dreams of being a real boy.

Many scholars regard the myth of Pygmalion—eventually canonized in Ovid’s Metamorphoses—as a probable inspiration for at least some of these tales. In Ovid’s telling, Pygmalion was a Cypriot sculptor who carved an ivory woman of extraordinary beauty in place of a wife. Though he knew it was madness, Pygmalion became increasingly infatuated with his creation and prayed for a living likeness. When he returned home from the feast of Venus and kissed the statue, she came to life. They married and had a son, the namesake of the city of Paphos.

D’Huy thinks the origins of the Pygmalion myths are much deeper than is typically thought. He noticed that Ovid’s version strongly resembles stories told by the Bara people of Madagascar, the Berbers of North Africa, and various tribes throughout eastern Africa; they all involve carvings or drawings that come to life and live with their creators. In a South African variant, for example, a tribal leader tries to abduct a recently animated woman from the sculptor who made her. The sculptor throws the woman to the ground and she turns back into wood. When d’Huy performed a phylogenetic analysis on various iterations of Pygmalion, he discovered that the Greek and Bara myths likely split from the Berber story three thousand to four thousand years ago. These nascent Pygmalion myths then spread to other parts of Africa and the Levant with migrating livestock herders.

Any contemporary interpretation of a story that potentially existed long before recorded history is necessarily speculative. Although the phylogenetic analysis of folktales and myths may benefit from the latest statistical techniques and software, it remains a new and uncertain science that many folklorists regard with a mix of intrigue and skepticism. And the vast majority of ancient tales surely perished with their tellers. If certain beloved stories really have endured for many thousands of years, however, they tell us something important about the origin and nature of narrative itself.

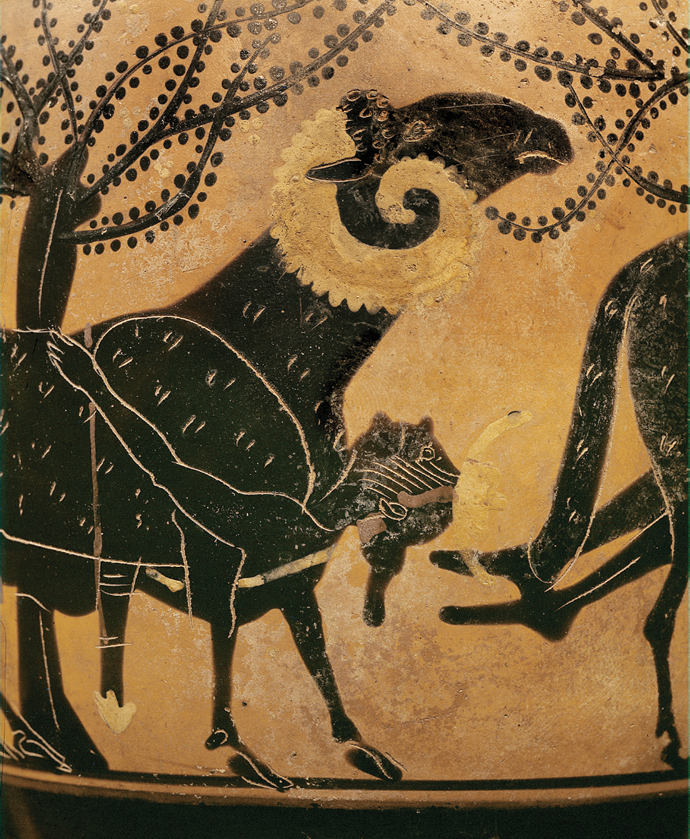

Ulysses escapes under the ram (detail), from a black-figured convex lekythos, c. 590 bc © Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York City

Every month or so, indigenous hunter-gatherers in the Philippines known as the Agta pick up their banana-leaf lean-tos and move to a different region of Northern Sierra Madre National Park. They fish, hunt, and forage along the coast and in the jungle. They sometimes trade for rice with nearby agricultural villages, but they are mostly self-sufficient—one of the few such groups still in existence. Since 2001, the anthropologist Andrea Migliano and her colleagues have routinely visited the Agta and have learned some of the group’s folklore from elders who tell stories around the campfire at night. Although living hunter-gatherers are of course not replicas of our Paleolithic ancestors, their cultures—combined with archaeological evidence—help compose a portrait of how humans likely lived before the widespread adoption of agriculture and densely populated settlements.

In the process of cataloguing the Agta’s tales, Migliano realized that many of them encouraged friendship, cooperation, and egalitarianism. In one story, the moon proves that it is as strong as the sun and the two agree to share dominion of the sky. In another, a winged ant snubs her flightless peers and tries to befriend birds and butterflies instead; after those creatures reject her, she returns to her colony, accepts her true identity, and becomes a queen. Similar themes run through the myths and folktales of hunter-gatherer societies around the world. When Migliano analyzed eighty-nine stories from seven different forager societies, she found that about 70 percent focused on regulating social behavior.

In 2014, Migliano and her colleague Daniel Smith, along with several other researchers, began surveying the Agta about the characteristics they valued most in their peers. To their surprise, storytelling topped the list—it was even more prized than hunting skills and medicinal knowledge. When they asked nearly three hundred Agta which of their peers they would most like to live with, skilled storytellers were two times more likely to be selected than those without such talents, regardless of age, sex, and prior friendship. And when they asked the Agta to play resource allocation games, in which they could keep bags of rice or donate them to others, people from camps with talented storytellers were more generous, giving away more rice, and esteemed storytellers were themselves more likely to receive gifts. Most profoundly, Agta with a reputation as good storytellers were more reproductively successful: they had 0.5 more children, on average, than their peers.

“There is an adaptive advantage to storytelling,” says Migliano. “I think this work confirms that storytelling is important to communicate social norms and what is essential for hunter-gatherer survival.”

“Little Red Riding Hood,” the tale of Polyphemus, and other ancient tales are all preoccupied with peril. They are populated by predators real and imaginary. They are replete with physical and interpersonal threats—in particular deceit. They confront characters with at least one crisis and force them to either resolve it or meet a terrible fate. Even the folktales of the Agta, which emphasize harmony, only do so through a sharp contrast with discord. When we try to define the qualities of memorable narratives today, we often fall back on clichés and tautologies. Stories need conflict, we say. Why? Because conflict makes for a good story. But maybe there’s a deeper reason.

Not only are ancient myths and folktales almost universally concerned with danger and death; they are blatantly didactic. If we remove their layers of symbolism and subtext—which have been interpreted and reinterpreted for millennia—and focus on their narrative skeletons, we find that they are studded with practical and moral insights: people are not always what they seem; the mind is as much a weapon as the body; sometimes humility is the best path to victory. Modern stories frequently plunge us into lengthy interior monologues, exhaustively describe settings and people’s physical features, delight in the random, absurd, and orthogonal, and end with deliberate ambiguity. The earliest stories were, for all their fantasy, far more pragmatic. Their villains were often thinly veiled analogies for real-world threats, and their conclusions offered useful lessons. They were simulations that allowed our ancestors to develop crucial mental and social skills and to practice overcoming conflict without being in actual danger. Though we may never definitively know what confluence of biological and cultural pressures hatched the first stories—though narrative has far exceeded its preliminary role in human evolution—it seems that our predecessors relied on stories to teach each other how to survive.

But fixating on the social benefits of storytelling elides an even more fundamental purpose: a story is really a way of thinking—perhaps the most powerful and versatile skill in the human cognitive repertoire. The world confronts the mind with myriad impressions, a profusion of other often perplexing beings, and an infinity of possible futures. The increasingly large brains of our ancestors, all the more attuned to the world’s complexity, needed a way to organize this overwhelming torrent of information, to pass the multiplicity of experience through a reverse prism and distill it into a single coherent sequence. Stories were the solution.

A story is a choreographed hallucination that temporarily displaces reality. At the behest of the storyteller, this conjured world may mimic perceived reality, perhaps rehearsing a past experience; it may modify reality, placing proxies of actual people in hypothetical scenarios or fictional people in familiar settings; or it may abandon reality for a realm of fantasy. Before stories, the human mind was only a partial participant in its own conscious experience of life, restricted to the recent past and near future, to its immediate surroundings and fragmented memories of other places. By telling stories, early humans gained unprecedented autonomy over their subjective experiences: they could dictate and record extensive histories and make intricate long-term plans; they could obscure, revise, and mythologize truth; they could dwell in alternate worlds of their own making. Storytelling transformed our species from intelligent ape to demigod.

So’yokmana Katsina (Ogre Maiden), a kachina doll carved from cottonwood root. Gift of the Estate of Mary Hemenway © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, PM# 45-25-10/28835

In the 1880s, the Prussian Ministry of Agriculture commissioned the German biologist Albert Bernhard Frank to systematically research the possibility of cultivating truffles—the pungent and delectable fruiting bodies of various fungi. As so many before and after him, Frank failed to find a reliable and economical method of fungiculture. Instead, he unearthed secrets that would eventually transform our understanding of ecology. Frank and other scientists had observed that truffles always grew around certain trees, such as beeches, hornbeams, oaks, and pines. In a series of meticulous studies, digging through tract after tract of woodland soil, Frank revealed that a gossamer mesh of fungal threads completely enveloped the root systems of many trees. “The entire structure is neither tree root nor fungus alone,” Frank wrote; it is “a union of two different organisms into a single, morphological organ.” We now know that massive lattices of fungi link the roots of neighboring trees, even those of different species, and that trees use these underground networks to exchange water, nutrients, and chemical messages.

Like trees in a forest, we too are rooted in the living mesh of another organism—in a web of story. We give life to the stories we tell, imagining entire worlds and preserving them on rock, paper, and silicon. Stories sustain us: they open paths of clarity in the chaos of existence, maintain a record of human thought, and grant us the power to shape our perceptions of reality. The coevolution of humans and stories may not be one of the oldest partnerships in the history of life on Earth, but it is certainly one of the most robust. As a psychic creature simultaneously parasitizing and nourishing the human mind, narrative was so thoroughly successful that it is now all but inextricable from language and thought. Stories live through us, and we live through stories.

The symbiosis of people and stories is unique in at least one regard. In order to survive, most symbiotic organisms need a specific partner and a narrow set of environmental conditions. In the wild, many seedlings will wither and die if their roots are not colonized by the right fungi; likewise, many fungi will fail to grow if they cannot find their botanical allies. Although we may rely on narrative to think, speak, and live, stories are not tethered to us in quite the same way.

Once recorded, a story has the potential to live longer and spread farther than any other creature. All it requires is a consciousness to inhabit—and that consciousness need not be human, or even organic. Stories that earn the widest audiences over the longest stretches of time are exceedingly likely to continue surviving in one form or another. And if a recorded story finds itself utterly alone, it is perfectly content to wait indefinitely for the arrival of a new audience, whether that audience be human, alien, machine, or something else altogether. Stories are capable of symbiosis that transcends species; they are also a kind of life that transcends biology itself. If any organism can achieve true immortality, it is surely the story.

Right now, Voyager 1, a space probe launched by NASA on September 5, 1977, is traveling at 38,000 miles per hour through interstellar space, more than 13 billion miles from Earth—about three and a half times the distance between the sun and Pluto. Of all the objects we have hurled beyond our orbit, it has journeyed the farthest. It carries a twelve-inch gold-plated phonograph record intended as a greeting to the universe. When the disc is played at the right speed, and its audio-encoded images are deciphered, it reveals a mosaic portrait of our planet and its creatures: salutations in fifty-five languages; folk music from China, India, Georgia, and Peru; concertos and quartets by Beethoven and Mozart; songs by Chuck Berry and Blind Willie Johnson; more than one hundred diagrams and photos depicting physics equations, DNA, human anatomy, elephants, dolphins, trees, the Golden Gate Bridge, cars, fishing boats, trains, a supermarket, and a dinner party; and a sampling of brain waves, recorded as the project’s creative director, Ann Druyan, thought about violence, poverty, the predicaments of civilization, and what it’s like to fall in love. The record is more polyphony than symphony, or perhaps polyphemy—a story told in many voices.

“This is a present from a small, distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts, and our feelings,” President Jimmy Carter said in a message included on the record. “We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.”