Coming home in the mid-Nineties to the new South Africa—new laws, new rules, new hope—felt not much different from coming home to the old one. De facto integration had been in place for some time, at least in public places: races mingling in the airport’s passport lines and at the glass barrier, my parents among them. But in most other ways life seemed to be going on as it always had. Except that this time, my father was dying.

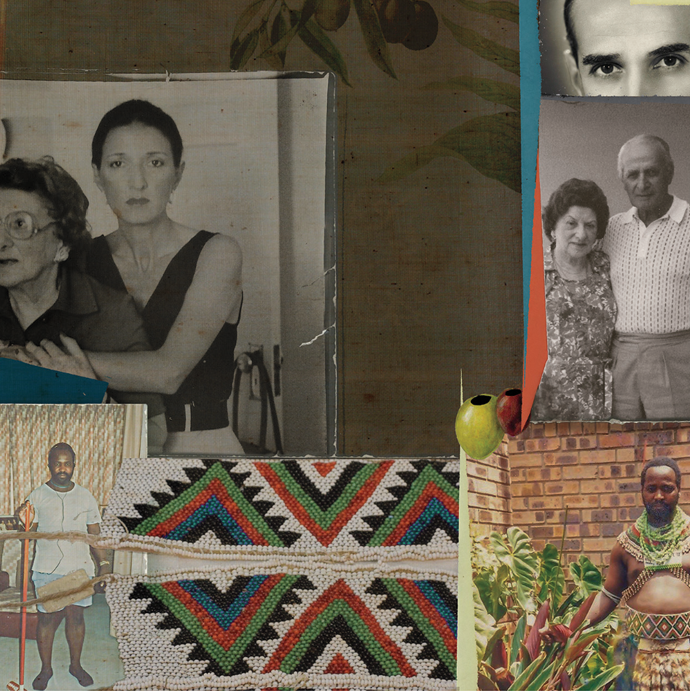

Illustration by Jen Renninger. Source photographs courtesy the author

He didn’t know this yet, and neither did I. We were going straight home from the airport for tea, he said, and then, if I wouldn’t mind, he’d like me to accompany him to the doctor. He’d pulled a muscle at golf, and it was giving him a devil of a time. The doctor had taken some X-rays, and perhaps, because I’d once been married to a doctor, I might make some sense of what he had to say.

Doctors in South Africa were still lying to patients then. But having lived for decades in the United States, where a patient’s right to know was taken seriously, I felt a bit like a thief, keeping to myself what the doctor was now telling me: an old man with lung cancer, six months at the most. No harm, he said, in letting my father go on thinking he’d pulled a muscle. What was the point of taking away his hope?

There might be wisdom in this, I could see. My father enjoyed enormous reverence for ill health. A paper cut on his finger had him sterilizing, salving, plastering, and then donning one of his several chamois finger cots that fastened around the wrist. Nonconforming bowel movements were reported in a tremulous voice so that menus had to be changed and Nicholas, the cook and general factotum, sent to the chemist for milk of magnesia. There had been several “heart attacks” over the years that failed to show up on any EKG. And now this.

“Master,” said Nicholas when we got home, “how the doctor he say?”

Nicholas had been told, of course—it was now the law—that “Master” and “Madam” were no longer permitted in the new South Africa, and also that he was not a “servant” anymore; he was a “domestic worker.” But they, masters and servants, were all too old to learn a new language, and, anyway, what had really changed? Not much. And neither Nicholas nor Regina (the maid/domestic worker) was likely to stage a linguistic revolution. They had jobs in a country falling into chaos, and were counting on the Master and Madam to stay alive long enough to see them through.

Nicholas had been hired as a man-of-all-tasks almost twenty years before. And then, as soon as the old cook died, he’d put himself forward to take over her job. He knew everything, he’d assured my mother, he’d watched when she wasn’t looking. And, indeed, he was soon turning out cakes and breads and biscuits, casseroles, roasts, and fried fish-and-chips for lunch on Saturday.

“Master,” he said, holding out a tube of anti-inflammatory cream, almost used up. “Master must buy some more.”

My father nodded. He sighed. Clearly, the cancer was tiring him out. And my mother, more aggressive than usual in her increasing dementia, had been making his life intolerable. “Where’ve you two been?” she demanded as we walked into the study. “I’ve been waiting ages for the drinks tray.”

My father sank into the wing chair, and Nicholas settled the footstool under his feet.

“Why don’t you answer me?” she demanded. “What are you hiding, you two?” She’d always had a canny way of seeing through to the truth. Dementia had only veered this talent slightly off course.

“Master,” said Nicholas, “must I bring the drinks tray?”

I began to wonder how much of a hand Nicholas had in her decline. There had always been drinks, of course—the tray rattling in at six with the soda siphon, olives, tinned asparagus, caviar if it was to be had. But now she was having two or three Scotches every evening and a few pre-lunch gin-and-its that Nicholas mixed for her if my father wasn’t around.

My father took out his pocket watch. “Too early, Nicholas,” he said. “Please go to the chemist for another tube of my cream. And take the old one with you.”

He settled back into the chair, closing his eyes. In the space of an afternoon, he seemed to have become more gaunt, more drawn, more sallow. I went to put my arms around his shoulders, longing to be able to give him back his life. To give him some of mine if I could.

“That hurts, darling,” he said. “Everything hurts these days, I’m afraid.”

The next morning, as I was having breakfast, Nicholas padded in. “Grace she’s here,” he said.

Grace, his wife, usually timed a visit for when I was going to be home. She lived inland, and it took her several days to make the journey to Durban, often bringing a child or two with her.

Nicholas held out a grubby piece of paper. “Grace she sick,” he said.

The paper had been torn from a prescription pad, with a doctor’s name and phone number printed at the top. I took it through to the kitchen.

Grace was sitting among the women on the stoep outside the kitchen, beads of sweat standing out on her forehead. In his spare time, Nicholas was an inyanga, an herbal healer, with a specialty in “women trouble.” And so every day, troubled women sat there, some of whom, like Grace, had made the long journey from the country, a few still wearing traditional beadwork and headdresses, with bare breasts and gleaming, oiled skin.

Grace stood up. Unlike Nicholas, she was tall and sober, with a good command of English.

“Grace?” I said. “What’s the matter?”

“That doctor, ma’am, he gave me a tablet. But I still am suffering.”

The doctor answered the phone himself.

“This is Dr. Freed,” I said. It was a title I’d never used except once to get my car out of a garage in New York City.

“Dr. who?” There was a faint note of alarm in his voice.

“What is the diagnosis on Grace Khumalo?”

“Hmm. Wait a minute. Oh, yes. Urinary tract infection. I gave her ampicillin.”

“Just one tablet?” I’d had enough UTIs myself to know that one tablet was less than useless. And I knew his type of doctor, too: an office on Berea Road, queues of Africans waiting to give him money for a pill or a shot. “You gave her one but she paid for ten?”

“Well, if I give them more, they just sell them, hey?” he said, his voice rising. “So what am I supposed to do? They never come back when you tell them to.”

I could have reported him, of course, but to whom? The country was in chaos, hordes were moving to the cities, setting up squatter camps, hoping for a better life, now that it was possible.

I hung up and phoned an old friend.

“Listen,” she said, “just go across the road to McCord’s and ask for Dr. Lee. He’s Chinese. He’s the best. We all go to him there, now that we can.”

The waiting room at McCord’s Zulu Hospital was jammed, the overflow sitting along the walls. Some breastfed babies, some slept, some had limbs or jaws bandaged up. Ongoing warfare was raging between two African political factions, Inkatha Freedom Party and African National Congress, and casualties were everywhere. I went up to the intake window to ask for Dr. Lee. But as soon as the clerk saw me approach, she gave me a those-days-are-over-madam look and slammed it shut.

And then, just as I was thinking I’d take Grace to my father’s doctor—why hadn’t I thought of this before?—I saw a small Chinese man in a white coat walking by.

“Dr. Lee?” I galloped up to him. “Dr. Freed. From America.”

“America!” He beamed.

“California!”

And, within the week, Grace, at least, was cured.

A few weeks later, my father came down with the pneumonia that would end his life. All hospitals in the area were overflowing by this time, even the once quiet and restful St. Augustine’s, where his doctor had secured him a room. The place looked like a dressing station during the Crimean War—people sitting or lying along the walls of the corridor, some half-dead already.

Doctors and nurses stepped over legs and bodies, the nurses harried and short-tempered. But even with a private nurse, my father soon developed bedsores, and then suffered the agony of an orchiectomy to remove gangrenous testicles. “It says in the Bible that a man should thank the Almighty every day for not having been born a woman,” he whispered to me after the ordeal was over. “Now I’m not so sure.”

Every morning and afternoon, I took my mother to visit him, and, after lunch, when she was sleeping, I took Nicholas. He would tiptoe to the bedside, slip out of his sandals, put his hands on my father’s forehead, and murmur incantations. In addition to his herbal practice, Nicholas was a prelate in a Zionist Christian church, for which he wore a long blue-and-white robe. And on certain Sundays he would dress in traditional Zulu costume—furs, skins, beads, shells—and go down to the soccer fields for faction fights with other Zulus.

But clearly the murmuring annoyed my father, although, public schoolboy that he was, he simply endured it, closing his eyes as if asleep. After a week or so, however, he could endure no more. “Don’t bring Nicholas here anymore, please, darling,” he said. “And you can keep your mother away as well.”

This was not difficult to do. Day to day, my mother forgot about the hospital, and so, when I arrived back home with Nicholas that afternoon, I just failed to remind her. Anyway, she was, as usual, impatient for the drinks tray. “The Master’s gone,” she said, handing Nicholas the keys to the liquor cabinet. “Damned shame, if you ask me, sending men of his age and stature off to war.”

Just as it seemed my father would live on and on, from one torment to the next, I came to the hospital one day to find the rabbi waiting for me outside his room. “Your father died an hour ago,” he announced. “Chayim aruchim. You may go in and take your last look.”

But I shook my head. Week after week, I’d watched death taking over and could not bear now to see what it had left behind.

“What is your father’s Hebrew name?” asked the rabbi, a pasty, unkempt man for whom my father had had little time.

“His Hebrew name?”

“Well, never mind.” he said. “We’ll look it up.”

As soon as I came home with the news, Nicholas rushed up to me and fell to his knees at my feet. Tears streamed down his plump, bearded cheeks. “What it will happen to Nicholas now, Madam?” he cried, looking into my face. “I am Nicholas, Madam! Where must Nicholas go without the Master he say?”

Not two hours from my father’s death, and I was a “Madam” myself.

The funeral was to take place the following morning.

“Madam,” Nicholas said, “I can bring my friend?”

I knew Nicholas’s friend, a lithe young Zulu with an easy smile. Often lately I’d seen him on the stoep, sitting among the women.

“Sometimes he help Master with a golf club,” Nicholas said, dropping his eyes. “The Master he know him.”

I had no objection to Nicholas bringing his friend, although I had a fair idea they’d both consider a Jewish funeral a rather shabby affair—no feasting, no singing, just the burial, a few prayers, and then a table of sweetmeats and a lot of sitting around.

“Certainly you can bring your friend, Nicholas,” I said.

Dressing for the funeral, my mother was in a fine mood. “Are you coming, too?” she asked Madelaine, her nurse.

We’d hired Madelaine as soon as my father went into the hospital. And she was a happy choice. Like my mother, she was the product of a Roman Catholic convent, and so, quite soon, Jew and Catholic, they had settled into the comfortable intimacy of schoolgirls.

“Just tell me again,” my mother said, squinting at herself in the mirror. “Where are we going?”

“We’re going to say goodbye to someone special,” Madelaine said, fastening my mother’s pearls.

I turned away. There was deadness everywhere now, even in irony.

“Madam,” said Nicholas, a few days after the funeral, “Grace she is wait for you.”

“Grace, Nicholas? I thought she went back home.”

He lowered his eyes, and I noticed for the first time his beautiful, long, curling lashes.

“Well, send her in then,” I said.

“Ma’am,” Grace said softly, closing the door behind her.

“Please sit down, Grace.”

She sat on the edge of a chair. “Ma’am,” she said, “it is not right.”

“What’s not right, Grace?”

“I must be the one to the funeral.”

“What?”

“I am the wife. Nicholas must push away that friend now.”

“You mean the friend who came to the funeral?”

She clicked her tongue in irritation. “When I lie in the bed, Nicholas he turns away. He says I must stay home, not come here anymore.”

Oh, Nicholas, I thought. “Oh, Grace,” I said, “does Nicholas turn away when he comes home for his holidays?”

But she just stiffened her spine. “I am the wife, ma’am,” she said again, sober, dignified, betrayed. “I should have been the one to the funeral.”

When I went in to say goodbye to my mother, she was propped up in her bedroom chair, her hair tied by Madelaine into two bunches and festooned with pink ribbons. A month since my father’s death, and already she was dressed like a child.

I bent to kiss her, but she chattered her false teeth at me and clawed her hands in the air.

“They do that when they’re sad,” Madelaine said, not lifting her eyes from the antimacassar she was crocheting.

“I’m sad, I’m sad,” sang my mother.

“Well, I’m sad, too, Ma!” I said. “I’m derelict! I’m unmoored! I’m without hope!”

She covered her eyes. A tear ran down her cheek. “Don’t shout at me, darling,” she said. “And please don’t leave it too long before you come back.”

“Any gifts?” asked the customs officer at JFK.

“No.”

“None? You live in South Africa?”

“No. I live here.”

“Why were you there for so long?”

“My father was dying. He died.”

“Oh, I’m sorry to hear that. When did he die?”

“March twenty-seventh.”

“So you sat shivah there?”

A few decades later, walking to my gate at JFK for a flight to Rome, I pass a South African Airways flight being called—South African Airways announces the departure of—and I stop dead. There they are: sandals in December, lined up for the long journey south. And suddenly it is as if nothing has been lost. As if home were not yet diminished by high walls and electrified fences, staggering murder rates, absurdly rich New Rich, and untold legions of poor. As if I could join that queue myself and my parents would still be waiting at the airport barrier, Nicholas ready with the tea. And my heart was not yet indifferent to the shabby jargon of hope.