There used to be the notion that Keats was killed by a bad review, that in despair and hopelessness he turned his back to the wall and gave up the struggle against tuberculosis. Later evidence has shown that Keats took his hostile reviews with a considerably more manly calm than we were taught in school, and yet the image of the young, rare talent cut down by venomous reviewers remains firmly fixed in the public mind.

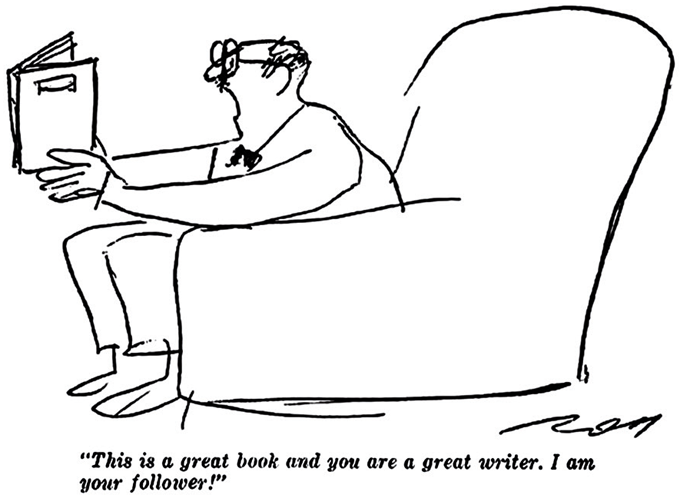

The reviewer and critic are still thought of as persons of dangerous acerbity, fickle demons, cruel to youth and blind to new work, bent upon turning the literate public away from freshness and importance out of jealousy, mean conservatism, or whatever. Poor Keats were he living today might suffer a literary death, but it would not be from attack; instead he might choke on what Emerson called a “mush of concession.” In America, now, oblivion, literary failure, obscurity, neglect—all the great moments of artistic tragedy and misunderstanding—still occur, but the natural conditions for the occurrence are in a curious state of camouflage, like those decorating ideas in which wood is painted to look like paper and paper to look like wood. A genius may indeed go to his grave unread, but he will hardly have gone to it unpraised. Sweet, bland commendations fall everywhere upon the scene; a universal, if somewhat lobotomized, accommodation reigns. A book is born into a puddle of treacle; the brine of hostile criticism is only a memory. Everyone is found to have “filled a need,” and is to be “thanked” for something and to be excused for “minor faults in an otherwise excellent work.” “A thoroughly mature artist” appears many times a week and often daily; many are the bringers of those “messages the Free World will ignore at its peril.”

The truth is, one imagines, that the publishers—seeing their best and their least products received with a uniform equanimity—must be aware that the drama of the book world is being slowly, painlessly killed. Everything is somehow alike, whether it be a routine work of history by a respectable academic, a group of platitudes from the Pentagon, a volume of verse, a work of radical ideas, a work of conservative ideas. Simple “coverage” seems to have won out over the drama of opinion; “readability,” a cozy little word, has taken the place of the old-fashioned requirement of a good, clear prose style, which is something else. All differences of excellence, of position, of form are blurred by the slumberous acceptance. The blur erases good and bad alike, the conventional and the odd, so that it finally appears that the author, like the reviewer, really does not have a position. The reviewer’s grace falls upon the rich and the poor alike; a work that is going to be a bestseller, in which the publishers have sunk their fortune, is commended only at greater length than the book from which the publishers hardly expect to break even. In this fashion there is a sort of democratic euphoria that may do the light book a service but will hardly meet the needs of a serious work. When a book is rebuked, the rebuke is usually nothing more than a quick little jab with the needle, administered in the midst of therapeutic compliments.

The editors of the reviewing publications no longer seem to be engaged in literature. Books pile up, out they go, and in comes the review. Many distinguished minds give their names to various long and short articles in the New York Times, Herald Tribune, and Saturday Review. The wares offered by the better writers are apt, frequently, to be something less than their best. Having awakened to so many gloomy Sundays, they accept their assignments in a cooperative spirit and return a “readable” piece, nothing much, of course.

© 1959 Elizabeth Hardwick, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

From “The Decline of Book Reviewing,” which appeared in the October 1959 issue of Harper’s Magazine.