Discussed in this essay:

Semicolon: The Past, Present, and Future of a Misunderstood Mark, by Cecelia Watson. Ecco. 224 pages. $19.99.

Four Men Shaking: Searching for Sanity with Samuel Beckett, Norman Mailer, and My Perfect Zen Teacher, by Lawrence Shainberg. Shambhala. 144 pages. $16.95.

Japanese Tales of Lafcadio Hearn, edited by Andrei Codrescu. Princeton University Press. 224 pages. $22.95.

Taormina and Mount Etna, Italy, by Adolphe Rouargue © Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan/De Agostini Picture Library/Bridgeman Images.

Pietro Bembo, a Venetian poet and scholar, staked his first claim to fame in a short book he published in 1496, when he was in his mid-twenties. De Aetna described, in Latin, a hike Bembo had made to the top of Mount Etna in Sicily. Even in summer, he observed, there was snow on the peak. An ancient Greek geographer, Strabo, had said that there wasn’t, but the evidence of one’s own eyes, Bembo wrote, was “no less an authority.” This was Renaissance humanism flexing its muscles—a few generations earlier, an ancient geographer might have carried more authority than a firsthand report—and it wasn’t the only instance of that in Bembo’s book. Various marks subdivided his text. One of them, which signaled both a medium-length pause and a semantic boundary inside a sentence, hadn’t been used for that particular function before. Between them, Bembo; his publisher, Aldus Manutius; and Manutius’s type maker, Francesco Griffo, were introducing the world to a new punctuation mark: the semicolon.

Bembo—who went on to have an affair with Lucrezia Borgia, edit Petrarch’s poems, become a cardinal, and help make Tuscan the basis of modern standard Italian—wasn’t a lightweight figure. Manutius wasn’t either, and the typeface he launched with De Aetna, which was also the first book to use italics, caught on. In humanist circles, for which he’d designed it, a primary value was eloquence, exemplified by the extremely long sentences of the ancient Roman orator Cicero. The Romans, like the Greeks, hadn’t used punctuation, and Cicero himself had expected readers to navigate his clauses by means of rhythm. Fifteen centuries later, that was a tall order. If you wanted your eloquence to be comprehensible, semicolons were a useful addition to the repertoire, and writers snapped them up. From Manutius’s printing house in Venice, they spread across Italy and up through France and the Low Countries, reaching England in the 1530s. One of the anonymous artisans who set the type for the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, published in 1623, inserted lots of them into his portions of Hamlet.

That compositor—whose high-handed yet slapdash ways created many puzzles for future scholarly editors—seems not to have had a very solid theory of how to use semicolons. In that, he wasn’t, and still isn’t, alone. “The semicolon,” Cecelia Watson writes in Semicolon: The Past, Present, and Future of a Misunderstood Mark (Ecco, $19.99), “is a place where our anxieties and our aspirations about language, class, and education are concentrated.” Lots of us, in other words, worry about semicolons—about where to put them, or about whether or not they’re addictive or pretentious or old-fashioned. Even if you agree that no other mark does as effective a job of supporting parallel constructions, or of separating listed items that need internal commas, uncertainty can creep back in under the guise of aesthetics. For every semicolon-fancier who has called it something cute, such as “the mermaid of the punctuation world—period above, comma below,” there’s someone else to call it “ugly, ugly as a tick on a dog’s belly.”

The haters are often, but not always, boys. Gertrude Stein, who considered the semicolon a jumped-up relative of the “servile” comma, was with James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Kurt Vonnegut, and Donald Barthelme in this matter. There’s an association with cluttered Victorian interiors and periwigged eighteenth-century savants, and perhaps there’s a fear of being likened to Jane Austen. The last would be a bad reason for avoiding semicolons even if Austen had overseen her books’ punctuation, which she didn’t. But there are more defensible reasons for lower-level unease. As Watson explains, the semicolon is historically unstable, gaining and losing functions in a tug-of-war with the colon. More generally, received wisdom tends to mix up punctuation’s oral performance-cuing and meaning-delimiting duties. Watson’s examples of virtuoso semicolon users usually have a strong preference one way or the other. Martin Luther King Jr. and Irvine Welsh—together at last—exploit the rhetorical rhythms of speech, while Herman Melville and Virginia Woolf are more interested in what’s possible on the page.

Watson, like me, has gotten the historical background from Malcolm Parkes’s unbelievably learned Pause and Effect: Punctuation in the West. Instead of doing a historical survey, though, she skips from Manutius to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century grammarians in order to get rules-based pedantry in her sights early on. In tone, her book is closer to Lynne Truss’s jokey Eats, Shoots & Leaves than it is to, say, David Crystal’s levelheaded Making a Point. When one of Melville’s reviewers uses the word “limbo,” Watson throws in a winsome footnote for any readers who might be thinking of the dance. But her chattiness is much less annoying than Truss’s, and her argument runs in a different direction. Being a stickler can be fine when you’re writing, she argues, but enforcing conventions can also be a way of bullying people, or worse. One chapter details an entertaining episode in which a poorly placed semicolon banned late-night liquor sales in Massachusetts. The next details a judge’s use of a similar slip to override a jury, in New Jersey, in 1927, and put an Italian immigrant to death.

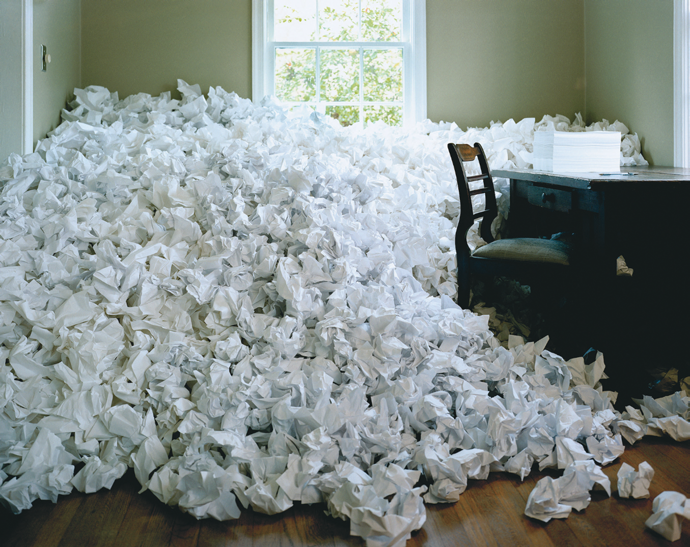

“Untitled (Perfectionist),” by Sarah Hobbs © The artist. Courtesy Hathaway Gallery, Atlanta

“How hideous is the semi-colon,” the narrator says in Samuel Beckett’s novel Watt. Beckett himself came to feel that the marks were “horrible,” and Nicholson Baker once suggested that Beckett must have seen them as “an emblem of vulgar, high-Victorian applied ornament, a cast-iron flower of mass-produced Ciceronianism.” If so, it would have been consistent with Beckett’s scorn for many things as an unhappy young man, which translated, when he was old and famous, into a reputation for being unapproachable. “Bastards of critics” and “bastards of journalists,” as he put it in a letter in 1957, weren’t often invited to the nondescript café on the Boulevard Saint-Jacques in Paris that he used for meetings. Still, Beckett could be got to if you had the right connections, or even just sent him a letter that caught his interest. By the time of his death, in 1989, a surprisingly large network of construction worker poets, half-mad vagabond actors, obscure writers and academics, and young future celebrities—Paul Auster was one of them—had grown up around him.

Lawrence Shainberg got in touch with him in 1979. Out of the blue, he sent Beckett a copy of Brain Surgeon, an account of the six months he’d spent shadowing Joe Ransohoff, a chain-smoking, tough-talking neurosurgeon at N.Y.U. (“Shit,” Ransohoff says, in Shainberg’s book, when a suction tube accidentally slurps up some healthy tissue from a patient’s brain. “There go the music lessons.”) Beckett found the book interesting. They met a few times, and Shainberg later published an essay about the inhibiting effects of his obsession with Beckett’s writing. Ransohoff and Beckett, however, weren’t the only charismatic figures to whom Shainberg developed powerful attachments. The impulse that led him to seek them out also brought him into the orbits of a famous Zen master, Kyudo Nakagawa, and Norman Mailer, whom he got to know in the Nineties. In Four Men Shaking: Searching for Sanity with Samuel Beckett, Norman Mailer, and My Perfect Zen Teacher (Shambhala, $16.95), Shainberg tries to make sense of his relationships with these oddly assorted gurus.

This isn’t an easy task, and it doesn’t help that a wish to escape from the mind’s restless sense-making was what made Shainberg go looking for gurus in the first place. In 1973, he explains, he went to a talk by Eido Tai Shimano, the founder of the New York Zendo (who was later forced out for exploiting his students sexually). Eido’s insights were so profound, Shainberg writes, that “I listened in a state of whiteout. When I left the Zendo, I could barely remember what he’d said.” The next morning, however, Shainberg briefly achieved transcendence from the questions that usually plagued him—questions to do with desire, and mind-body dualism, and why his brain wouldn’t shut up. Two sentences—the seeds, he was immediately convinced, of a great philosophical novel—drifted into his mind: “ ‘Brain damage,’ I said. Then I fell to the ground.” The rest of the novel didn’t come as easily as he hoped, but the research gave him a non-fiction book in the form of Brain Surgeon.

Shainberg has no trouble diagnosing his problem with meditation and writing. The better he got at banishing thoughts from his mind, the harder he found it to organize them on paper. But his mentors seemed reluctant to consider this problem in all its fascinating dimensions. “No need mix up,” Kyudo told him. “When you shit, you wipe anus, no? Then flush paper, no? No need keep paper, walk around shit in your pocket.” Mailer—who remarked that Kyudo “sounds like a total asshole”—gave Shainberg a blurb for his first book on Zen, because, he said, “It shows me why I’ve always hated Zen.” He too had recourse to bodily functions when Shainberg began to explain the difference between nothingness and emptiness. “I’ve got to take a piss,” Mailer said. “Let’s talk about it when I get back.” Beckett—who said delicately that Mailer was “a bit copious for me”—also tried to nudge Shainberg away from self-analysis. “Your line is witnessing,” he told him.

It would be easy to write Shainberg off as someone whose real problem is extreme self-absorption. On the morning of 9/11, he reports, he phoned Kyudo to continue an argument about the propriety of letting older visitors to the Zendo sit on chairs. Elsewhere, a misplaced modifier inadvertently implies a large Zen ego: “Beautiful and soulful, I consider her the quintessential dog.” But Shainberg is slyer than all this makes him sound. His depictions of the elderly Mailer, who says things like “I can’t dominate shrimp anymore,” suggest that Beckett was right about Shainberg’s gifts as an observer. He brings out the comedy of trying to learn from “a teacher for whom thought’s arrival in the brain is considered an unfortunate development,” and comes across, at times, as an Upper East Side version of the perplexed central character in Beckett’s novel Murphy. Shainberg ends with a Zen insight, but Beckett had reached a similar conclusion back in 1987. “I can’t be of help with your problems,” he wrote to Shainberg. “I suspect you prefer them insoluble.”

“Sincere mopping,” in Shainberg’s telling, was the most strenuous activity that Kyudo prescribed for himself and his students. According to the Japanese Tales of Lafcadio Hearn (Princeton University Press, $22.95), edited by Andrei Codrescu, traveling Buddhist priests were once made of sterner stuff. In a story called “Rokuro-Kubi,” a priest called Kwairyo, a former samurai, thinks nothing of sleeping in the open in a haunted wilderness. “His body was iron; and he never troubled himself about dews or rain or frost or snow.” When some apparently friendly woodcutters turn out to have detachable heads that fly at him with hostile intent, Kwairyo takes it in stride, “plucking up a young tree” to use as a baseball bat. He keeps one of the heads as a souvenir, which later impresses a highwayman: “You!—what kind of priest are you? . . . It is true that I have killed people; but I never walked about with anybody’s head fastened to my sleeve.” The robber offers to buy the head, the better to frighten his victims, but the priest lets him have it for free.

A rokurokubi, a long-necked woman, with an inugami dog spirit, from the Bakemono Zukushi, a scroll of various shape-shifting creatures from Japanese folklore. Courtesy the Harry F. Bruning Collection of Japanese Books and Manuscripts, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

Lafcadio Hearn—who got hold of this story, and many others, while living in Japan from 1890 until his death in 1904—stands near the beginning of a long line of literary Japanophiles that runs all the way to Shainberg by way of Ernest Fenollosa, Ezra Pound, and Alan Watts. He got his name from the Greek island of Lefkada, where he was born, in 1850, to a local noblewoman and an Irish surgeon attached to the British Army. His parents took him to Dublin, but their marriage didn’t last, and after a sequence of events resembling a Wilkie Collins novel—the ingredients included religious tensions, a spell of near homelessness in London, and an unscrupulous financial adviser to Hearn’s aunt—Hearn washed up penniless in Cincinnati at the age of nineteen. In spite of his bad eyesight, which he dealt with by carrying a magnifying glass and a telescope, he became a star reporter for the Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, with a salary of twenty-five dollars a week.

Hearn had been hired to write bloodcurdling accounts of local murders, but he had higher ambitions. He translated Maupassant in his spare time, and his background seems to have made him uncomfortable with the racial hierarchies that prevailed in the British Empire and the United States. A short-lived marriage to an African-American woman got him fired from the Enquirer, and he moved to New Orleans, where he took an interest in Creole folklore and the exotic tales of the globe-trotting French novelist Pierre Loti. A commission from Harper’s Magazine took him to the French West Indies, and then to Japan, where he found work as an English teacher in Matsue, married the daughter of a local samurai family, and settled down as a traditional Japanese paterfamilias under the name Koizumi Yakumo. His folktale collections are classics in Japan, and, at the start of the twentieth century, he was one of the English-speaking world’s go-to guys for stories of the mysterious East.

In other words, Hearn ended up resembling a character out of Jorge Luis Borges, who mentioned him in The Book of Imaginary Beings. A danger with writers on whom Borges drew is that their work can be less appealing in reality than he makes it sound. (Richard Francis Burton, Borges’s favorite translator of The Thousand and One Nights, was an interesting man in many ways, but his eccentric stylistic choices make his translation pretty much unreadable.) Hearn started out as a purveyor of florid, semicolon-rich sentences of the kind that impressed H. P. Lovecraft, and there’s more than a whiff of the fin de siècle in the metrical prose—“For the name was the name of the story of a song that bewitches men”—in which he wrote the first story in Codrescu’s selection from his work. But most of the stories aren’t like that. Hearn, “converted by [his] own mistakes,” came to reject excessive adornment, and Codrescu has also trimmed the ethnographic musings that cluttered his books.

The result is a weird—in a good way—collection of stories, gathered from oral and written sources by Hearn. In one, a despondent lover lets a “Shark-Man” move into his garden pond. In another, a man’s wife, and—the kicker—parents-in-law, turn out to be willow trees. There are several examples of the vengeful ghosts of long-haired young women, who later made it big in horror movies, but there’s also a sad story in which a dead wife is less angry, and, in “Diplomacy,” which opens with a condemned prisoner threatening to take postmortem revenge, the twist is that “the dead man gave no more trouble. Nothing at all happened.” Hearn’s occasional interjections about his source material—“Here, in the Japanese original, there is a queer break in the natural course of the narration . . . ”—come across as pre-echoes of Italo Calvino, or indeed of Borges. And there’s an intriguing web of motifs: doppelgängers, mysterious boxes, the uncanny power of writing. Taken together, it all implies that Hearn’s Japanese admirers know what they’re talking about.