The San Luis Valley in southern Colorado still looks much as it did one hundred, or even two hundred, years ago. Blanca Peak, at 14,345 feet the fourth-highest summit in the Rockies, overlooks a vast openness. Blanca, named for the snow that covers its summit most of the year, is visible from almost everywhere in the valley and is considered sacred by the Navajo. The range that Blanca presides over, the Sangre de Cristo, forms the valley’s eastern side. Nestled up against the range just north of Blanca is Great Sand Dunes National Park. The park is an amazement: winds from the west and southwest lift grains of sand from the grasses and sagebrush of the valley and deposit the finest ones, creating gigantic dunes. You can climb up these dunes and run back down, as I did as a child on a family road trip and I repeated with my own children fifteen years ago. The valley tapers to a close down in New Mexico, a little north of Taos. It is not hard to picture the indigenous people who carved inscriptions into rocks near the rivers, or the Hispanic people who established Colorado’s oldest town, San Luis, and a still-working system of communal irrigation in the southeastern corner, or a pioneer wagon train. (Feral horses still roam, as do pronghorn antelope and the occasional mountain lion.)

It’s also not hard to picture oneself as a homesteader. The land is not free but it is cheap—some of the cheapest in the United States. In many respects, a person could live here in this vast, empty space like the pioneers did on the Great Plains—except you’d have a truck instead of a mule, and some solar panels, possibly even a cell-phone signal. And legal weed. If you are on disability or receive veterans’ benefits, you might even get by without having a job, though if you have no income, things can get tricky, especially when winter comes around.

The crossroads of Grant Avenue and MM 14th Street, with Blanca Peak in the distance, San Luis Valley, Colorado (detail). All photographs from Colorado, May 2019, by Lisa Elmaleh for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

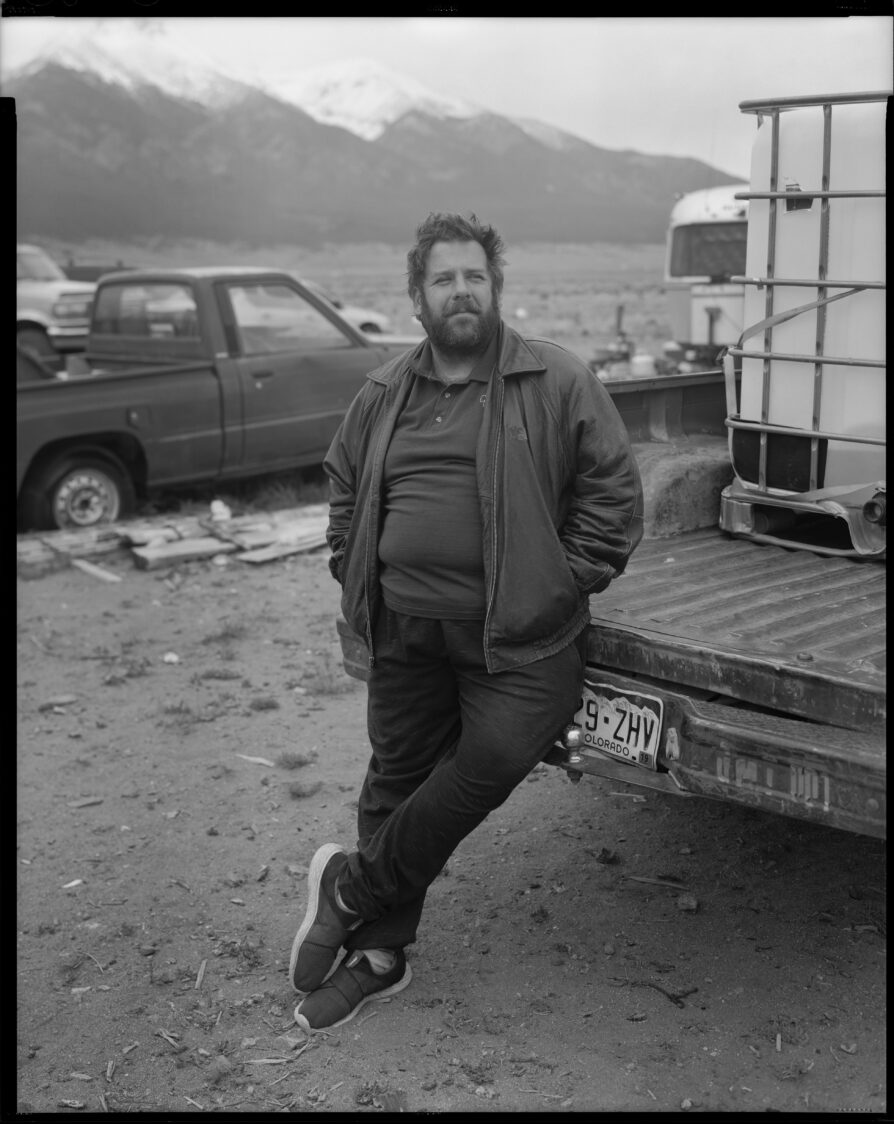

Matt Little knows the hardships of living in the valley firsthand. He grew up one of eight kids in Weirton, a former steel-mill town in West Virginia, saw combat in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, and then in 2013 lost his wife to C.O.P.D. and their house to a fire. He decided it was time to start a new life. He knew about Colorado from sportsmen’s magazines such as Field & Stream and, from googling “cheap land Colorado,” had an idea that the San Luis Valley might be a good place to settle. Among his many skills was food preparation (he had managed a Ponderosa Steakhouse) and, en route to a food-service job at Adams State University in Alamosa—the biggest town in the valley—he headed west in his Ford F-150 with his grown son, a paranoid schizophrenic, in the passenger seat.

It was early 2016. To save money for the land he hoped to buy, they essentially lived out of Matt’s pickup truck. From March to October, that was their home. But they also moved around. “We did a lot of free camping on Lake Como Road, off of 150, Smith Reservoir, Mountain Home Reservoir. We stayed at the trailer park [in Blanca]. I was considered homeless, but I didn’t consider myself homeless—I didn’t see us as that bad off.” In October, Matt bought a camper for the bed of the pickup, which allowed them to sleep indoors instead of outside in a tent. It was starting to get very cold at night, and winter temperatures in the San Luis Valley can drop to negative fifty degrees Fahrenheit.

But Matt, a jack-of-all-trades, could find only odd jobs. It was not for lack of trying. His attitude toward work is: “Every job is honorable. I spent five years throwin’ trash in a side-loader [garbage truck]. Pushin’ a broom at the grocery is honorable.” And then one morning in March, as he approached a general store in the little town of Blanca, he saw Calvin Moreau, a formerly homeless person working for a group called La Puente, affixing a posting for a job to a bulletin board. The flyer read: “Do you live in this area? La Puente’s Rural Outreach Services is in search of a case manager. No experience necessary. Military Service a plus. Requires great communication skills.”

“He was the first one to call,” says Judy McNeilsmith, La Puente’s director of program services. “And maybe more important, he was the first one to answer when I started calling some of them back. Being reachable is very important for this job.” She and her boss, Lance Cheslock, La Puente’s longtime director, liked other parts of Matt’s background, too, including that he was a veteran and lived in the valley and was eager. Two months after hiring him, they agreed to let me accompany Matt as he did outreach on the flats—La Puente’s term for the interior of the San Luis Valley, lightly populated prairie lands outside towns and between the mountain ranges.

I’m originally from Colorado, but people like Matt and his neighbors were unfamiliar to me. I know about mountain towns, and the national parks and forests that support the tourist economy, and I know a bit about ranching. But the expansive San Luis Valley—about the size of Massachusetts, nearly 8,000 square miles—is different. Much of it is privately owned and for sale as small, affordable lots. Poor people can become homesteaders of a sort. The poverty rate in the valley is between 20 and 25 percent. The election of Donald Trump had made me feel ignorant of the poor rural parts of my home state. And the kind of off-grid living practiced there went against my preconceived notions about off-grid living. In my mind, most off-gridders were trying to live lightly off the earth by reducing their needs, unplugging from both utilities and society’s expectations of achievement. The upscale among them embraced things like the Taos-based Earthships, often expensive, fancifully designed houses that incorporate advanced technologies to recycle water and control indoor climate. I imagined the less affluent among them as neo-hippies with environmental consciousness: into the virtue of not needing much and appreciating the creative reuse of discarded materials, communalism, tiny houses, and outsider art.

Some of the valley’s off-gridders were like this. But more of them were just poor and wanted a different life—one with more self-reliance, fewer bills, and, in many cases, lots of distance from neighbors. They arrived pulling trailers or with old R.V.s and set up camp. Sometimes they would build something, but often the trailer became the building block, with shacks or Tuff Sheds added on. They drove Fords, not Toyotas. Their political views tended toward the Trumpian: antigovernment, pro-gun, America-first, build-the-wall. Among them were doomsday preppers, Christian homeschoolers, self-proclaimed sovereign citizens, weed lovers, and Hillary haters. Some might have previously lived near a coast but more probably came from the heartland, many from the South. And most were very poor. The San Luis Valley, with its cheap land, was a sort of magnet for these off-gridders. There were a few hundred of them in total. Nationwide there are probably several thousand people living off the grid. No authoritative numbers exist, but off-grid life seems to be growing, often in states with cheap land (Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri), sunshine and cheap land (Nevada, Arizona, Texas), and/or frontier appeal (Alaska, Idaho).

Matt Little preparing to deliver firewood to homesteaders in the San Luis Valley

Matt and I talked on the phone the night before we first went out: Don’t wear tan or blue, he advised me, as those are the colors of county code inspectors and sheriff’s deputies. We met in a parking lot in Blanca, and when I climbed into the front of his dusty red pickup truck, I saw that his shirt was maroon. “I told Lance it couldn’t be those other colors, and we settled on this.” The outside of the truck was covered with mud; the inside was blanketed with dust and smelled of cigarettes.

He’d already been to the local spring to fill his water tank, a chore he performed daily just past dawn. Now that he had a job, Matt had rented a small place on the prairie for himself and his son, but, like most homes in this part of the valley, Matt’s house lacked running water. We filled the 275-gallon cubical plastic tank in the bed of Matt’s truck, drove a half hour back to his house to drop off the water, and then set off on the day’s outreach rounds.

During his first few weeks, the job was almost entirely cold-calling, he said. Now it was maybe two-thirds that, and the rest involved checking in on people he’d already met. We would do that today.

First we checked in on Diana and Wilene Hubbard-Hall, a recently married couple, who had arrived from Oklahoma a few months before, on the run from city life and corporate America. They called their little house at the bottom of Blanca Peak the Muumuu Ranch. Among their many dogs was a Chihuahua dressed in a leopard-skin sweater “so the hawks won’t eat him.” Next we visited Charles Leroy Harris, sixty, a retired plumber, and his wife, Cate, who had left suburban Denver “after the gang shootings got too bad” and now lived in a shed. An Air Force jet roared overhead, alarmingly close to the ground. Inside the shed, they had added a loft where they sometimes slept, more often after they found a rattlesnake inside the little marijuana greenhouse they had built in front. We passed a family from Pueblo who were engaged in the very first act of settlement: scraping a patch of land clear with shovels. It’s where the house will go, the man explained to Matt after we stopped. Matt told the family that he was about to do the same thing. He gave them a card and said that when they were ready he could bring some wood.

It is like the frontier but also not like the frontier. Matt believed that many households seem to have been attracted to Colorado by the decriminalization of marijuana in 2012—before then, only a handful of people had lived off-grid on the prairie. People commonly grow the plant themselves (legal to do in small quantities, but the allowed quantity is often exceeded), though where there’s a lot of marijuana there is something to steal, which might account for some of the pit bulls and guns I saw. And other drugs aren’t far away: stop the meth and the heroin pleads the sign outside a garden store in Alamosa. Where there are drugs there is paranoia. And in the valley, that paranoia takes a particular form: fear of the power of government manifests as a generalized kind of unease, which, I imagine, was less a feature of life on the American frontier one hundred years ago than it seems to be today.

If the last presidential election taught me anything, it’s that journalists based in New York need to pay attention to life outside cities. And I was further intrigued by La Puente. The group runs one of the country’s oldest rural homeless shelters. Cheslock told me that more and more people who show up at the shelter, especially in winter, have been trying to live out on the prairie. In good weather, the large area between the mountain ranges has many appeals: incredible views, eagles and other wildlife, and land you can buy for a song. Five-acre lots on the prairie are typically priced at $3,000 to $5,000. (Land costs a lot more around the mountainous edges or in towns, where more people live.) But only the hardy can make it here year-round. The cheap land is almost all treeless and miles from anywhere, and the valley is famously windy. Settlers will typically have a few solar panels hooked up to batteries for basics such as lights and a refrigerator, but beyond that you need money for gasoline, you need water, and, when it gets cold, you need a reliable source of heat.

In 2015, La Puente realized that many attempts to live on the prairie ended with homesteaders presenting themselves at the shelter. The workers there heard stories of people skipping diabetes medication because they didn’t have gas to get into town, or running out of food, or being isolated in abusive relationships. While the valley has approximately equal numbers of white and Hispanic people, poor people out on the prairie tend to be white. But it was all kinds of people. Lance’s scouts reported that an African-American woman and her four children were living in an unfinished house with little heat and no water. “We were getting stories like that and collectively thought, We need to be out there,” said Lance. “We should have known this long ago. But, like everyone else in the community who drives on paved roads, we hadn’t paid attention.”

A grant was secured from a group called Caring for Colorado, with the premise that helping far-flung poor people to become engaged was likely to improve their health, even if that didn’t happen overnight. Rural outreach could begin with a load of free firewood, but then it would move on to other things: Did residents need help picking up a prescription? Could they use a ride to (or help making) a medical appointment? So far, Lance told me, the initiative was off to a strong, if limited, start. The valley was so big that Matt Little couldn’t possibly cover the entire area. The first outreach worker they had hired had hurt himself loading wood and was out on disability. I was impressed by La Puente in just about every way. And I was curious about the apparent self-exile of some on the prairie. I wanted to learn about this kind of American wilderness—the one with people in it. I asked Lance if he could use another volunteer. He said yes.

Wilene and Diana Hubbard-Hall in front of their house

So now I needed (1) a truck and (2) a place to stay. For the first, my sister in New Mexico started scouring Craigslist and helped me buy a pickup truck from a used-car dealer in Española. The second problem was a little harder to solve. I would never have the experience or resourcefulness of a veteran outreach worker, but I could live out on the prairie and maybe understand a little bit better what that was like. The challenge was that there are no apartments or Airbnbs in the area and virtually no market in rental properties. I thought of buying land and putting a trailer on it, which I probably could have accomplished for $7,000 to $8,000. But everyone I floated this idea by warned me that during the weeks I wasn’t there, I should expect the trailer to get broken into, if not stolen. Such was the vulnerability of property on the flats—and the poverty of some who lived out there.

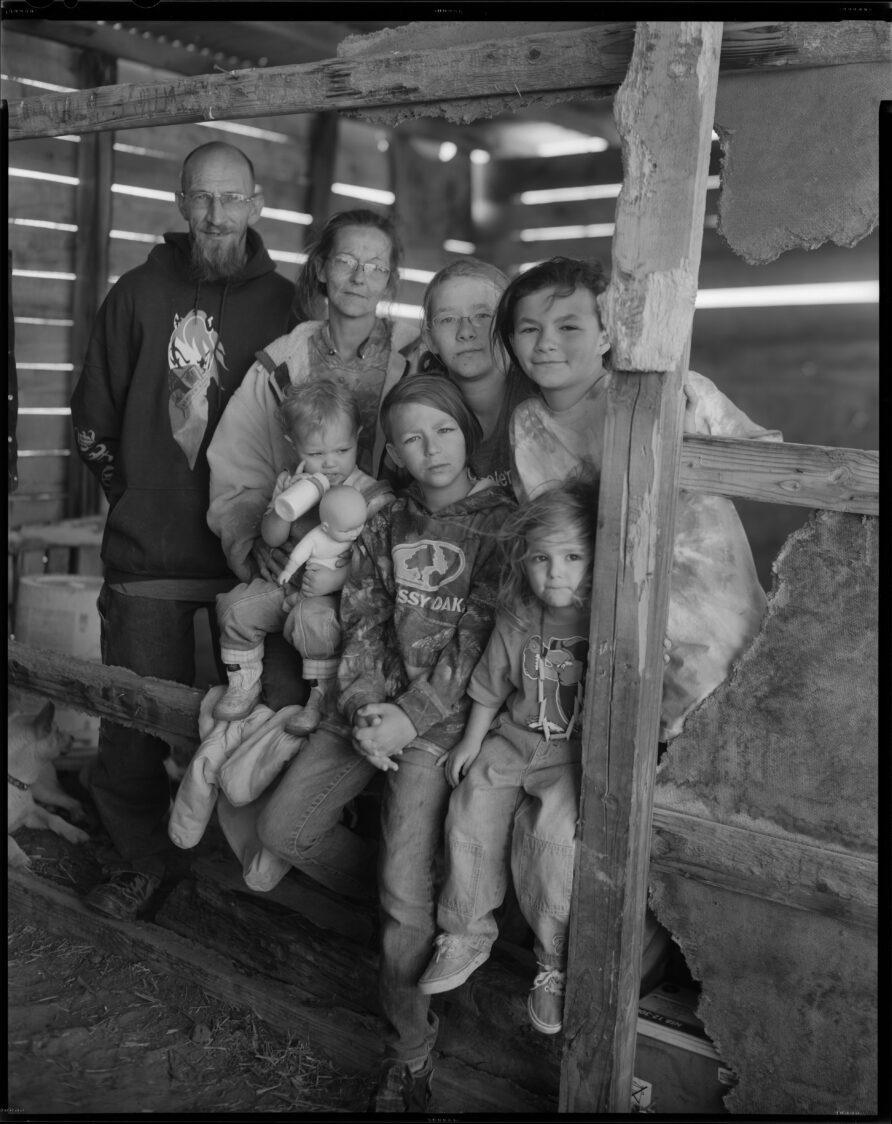

In Alamosa, I had overnighted in the spare bedroom of a longtime La Puente volunteer, Geneva Duarte. When I told Geneva my predicament, she offered to sell me the twenty-five-foot camper trailer in her driveway. It was twenty years old—she had bought it used and kept it mostly for fishing vacations with family in the summer. It was in decent shape. But where to park it out on the prairie? Her friend, Teotenantzin Ruybal, had a solution. Tona, as she is known, is the longtime director of the La Puente shelter. She is in constant contact not only with shelter guests but also with people who make use of the organization’s other services, including the outreach office. There she met a family from the flats interested in making a little money. Frank and Stacy Gruber had five daughters who ranged in age from just a few months to thirteen years old. They homeschooled the children, and they also had six dogs. They were open to the idea of my parking a small trailer on their property—where there was almost always somebody around—in exchange for a modest rent. My idea was to spend at least a full month out there, starting in mid-December 2017.

I had hoped to tow the trailer with my truck, but the hitch ball was the wrong size. A friend’s pickup was available, but it had a breathalyzer attached to the ignition, the result of a D.U.I., and, alas, my friend had been drinking. So I called Matt Little, and a couple of hours later he was hitching the camper to the back of his pickup.

As it happened, the old-style electrical plug of my trailer wouldn’t fit into the outlet in Matt’s truck, so my trailer’s brake lights and running lights wouldn’t work. The solution to this kind of problem, in the San Luis Valley, is to get onto a dirt road as soon as possible, since the cops seldom patrol there. We were about fifteen minutes from the dirt roads, and once there we stayed on them for the next hour.

Though I was worried about what effect the jostling might have on the plates and glasses in the cupboards of the trailer, basically I was thrilled. The passage from grid to off-grid in the San Luis Valley takes place in a scene of alpine splendor. Looming in front of us was snow-covered Blanca. In much of Colorado, public land surrounds major peaks. But not in the valley: there are many sheds, trailers, and shipping containers, both in current use and abandoned, all around the skirt of the mountain, grandeur towering over the less grand.

I was intrigued to see that Matt actually needed to consult his map as we went south—though the valley is huge, he knew where most things were. Down south near New Mexico, though, where I’d be staying, there were many unmarked dirt roads, and often they weren’t in a perfect grid. Lance had loaned me a DeLorme road atlas, which divided Colorado into ninety-four pages and offered a close-up of practically every area. But the flats—five regions of the prairie where people might try to live, per Lance—were so huge that the atlas was not up to the task. Specifically, it did not include details on the hundreds of dirt roads that had been created there in the 1970s, when a handful of giant historic ranches were bought up and then subdivided by developers. These were the crudest kind of early subdivision, consisting of nothing except a grid of dirt roads and the occasional street sign. Their creation had been driven by a marketing innovation: mail-order land. Ads in national newspapers and in publications such as TV Guide read: 5 acre ranch only $1995. $30 a month. relax or play in an uncrowded world. Most of the five-acre lots had never been built on, and, over time, most of the signs that I imagined had once been there had fallen over or otherwise disappeared. Some of the area could be navigated by GPS apps such as Waze or Google Maps, but much information was missing or wrong, or simply inaccessible because of weak or nonexistent cell-phone signals out on the flats.

“Yeah, those don’t really work,” Matt told me as I riffled through the big DeLorme atlas. “You need to get one of these.” He held out a tattered map of a kind I’d never seen. “It’s a DIY Hunting Map,” he said, explaining that the brand was well known to hunters in the Rockies. “You can get one in Monte Vista.”

I took it and helped Matt navigate to Frank and Stacy’s place. It was a mobile home with a lot of stuff around it: wooden pens for animals, a small bulldozer, cracked solar panels and a generator, discarded plastic toys, trash around a burn pit and elsewhere (there is no garbage collection on most of the prairie), and several dogs who ran up to our truck after Matt tapped the horn. The dogs were friendly and so was Stacy, who emerged from a back door holding her youngest daughter, Raven, just a few months old. Stacy told us to wait and she’d get Frank. He came out a few minutes later wearing a Denver Broncos T-shirt and clearly in pain. Several inches of his colon had been removed at a hospital in Colorado Springs two weeks before. Their daughters watched us through the windows as the dogs calmed down and we were able to talk. He had been a house painter and drywaller but hadn’t been able to work for a while. They pointed out a promising spot about two hundred feet from their house.

Matt and I leveled the ground and arranged bales of straw around the perimeter to keep out some of the wind. It was just above freezing on the mid-December afternoon, but the wind was blowing and by night it would be very cold. Geneva had loaned me a small generator, and I’d brought some big jugs of water.

Stacy asked the two oldest girls to give me a tour. Thirteen-year-old Trin and ten-year-old Meadoux together introduced me to their three Nigerian Dwarf goats and a regular-size billy goat, a Vietnamese potbellied pig named Pumbaa (super tame, slept with one of the girls for a while in her bed), a cat, a fat rabbit, and some chickens. The five dogs ranged from an aging St. Bernard (the largest) to a Chihuahua (the most fierce). Through a window we could see a cockatoo inside. Most of the animals were rescues, Stacy said. When the front door opened, I could hear the cockatoo squawk and then speak in a woman’s voice. Stacy said it also spoke in the voice of a man they deduced had been named George, because the woman said reassuring things such as, “It’s okay, George.”

“But sometimes George uses bad words,” Meadoux informed me.

“Oh, like what?”

She didn’t want to say. Stacy dared, though. “George will say things like [she lowered her voice], ‘Shut the fuck up’ or ‘Shut the fucking door.’ ” The girls giggled. “We think George was abusive,” Stacy added.

There was a lot to dust and straighten out after the long trip on dirt roads. And then there was the fairly urgent task of figuring out how to keep warm in the trailer. In the short term, it was not a problem: it had forced-air heat, and at Geneva’s its little battery had kept the trailer warm overnight. That evening, I made my bed, a double, spread a heavy blanket and comforter on top, and quickly fell asleep.

It couldn’t have been more than a couple of hours before the heater stopped running. And the lights wouldn’t come on. I knew the battery was dead.

I hadn’t yet set up a generator, so that wasn’t an option. But I had brought with me an extremely heavy, polar-weight, down sleeping bag that I had used in the Himalayas while reporting there. Shivering, I got inside, covered the sleeping bag with a blanket and a comforter, and, to some degree, went back to sleep.

The problem, come morning, was in getting out of the sleeping bag. I was wearing thermal underwear, but the temperature inside the trailer, according to a little thermometer, was negative seven degrees Fahrenheit. I dressed as quickly as I could and then headed outside to pee . . . but condensation inside the trailer had frozen the metal door shut. I guessed I could kick it open if I really needed to, but I didn’t want to damage it—the trailer had lasted twenty years and this was only my first day inside! With all the patience I could muster, I pushed around its edges until it swung open and I could step out.

Luke Kunkel, who has lived in the San Luis Valley for five years, drives several miles to fill his water tank at least once a week.

Back inside, I resolved to at least brush my teeth before getting in my truck and heading into town: I wanted to show myself that, though very cold, I could still do most of what a normal person might do in the morning. The jugs of water I’d brought were frozen, but somehow at night when the cold had woken me I’d anticipated that: I was particularly proud of having thought to put a filled water bottle into my sleeping bag so that it wouldn’t be frozen when I awoke. I found the toothbrush I’d left by the kitchen sink the night before, applied toothpaste, and . . . yow! With the bristles completely frozen, it felt like a jagged rock in my mouth. This was a bridge too far. I found my keys, went out to the truck, prayed as the engine slowly turned over, then rejoiced when it started up.

My goal was to meet one new person on the prairie every day. That might not sound very ambitious, but given that I was a complete outsider I thought it was reasonable. There were some residents whom my rural-outreach predecessor, Robert Lockwood, had gotten to know. That afternoon, after buying gasoline for my generator at the nearest gas station, about forty minutes away, I began my outreach.

The day was cloudy and cold. In three hours, I saw only one other vehicle on the road and it was far away, visible thanks to the trail of dust that rose behind it. Most settlements were far from one another. It took me a while to understand which might be worth approaching and which were abandoned. One obvious clue, once I thought to look for it, was the road: a handful of roads had plenty of tire tracks, but others had none at all: nobody had been down them in a long time. Another clue, which I was embarrassingly slow to appreciate, was whether smoke was coming out of a chimney pipe atop a trailer or shack or there was a generator running outside. If a home had neither (and most places had neither), then nobody was there . . . and anybody who stopped his truck at the end of a driveway and honked was a fool. For several early stops, that fool was me.

Other times, though, a place likely had somebody home who just didn’t want to see me. That was the case with a small compound (trailer and shed) off a more-traveled road with a painted wooden sign out front that advertised piano lessons and listed a phone number. I was attracted to it by the suggestion that the inhabitants appreciated the finer things in life, and also by the possibility that, appreciating the arts, they might be less likely to shoot me. The place had no dogs chained up in front, which was itself a welcome sign. Heat from the chimney, I couldn’t tell. The tire tracks heading up the driveway, past the closed gate, looked pretty new, and I could see part of a truck or S.U.V. behind the house. I honked, and a few minutes later honked again. Nothing.

But less than a mile away, I spotted another place, with a Jeep Wagoneer idling out front. A man was inside. I stopped a few yards away, rolled down my window, and waved at him. A moment later he cracked his own window. I climbed out of my truck and, in a show of my confidence and good intentions, walked over to him.

“Hi, I’m Ted, from La Puente,” I said.

“Hey,” he said. His green Corona baseball cap matched the color of his eyes.

I told him about the firewood.

“I don’t usually accept charity and stuff,” he said.

“I get that,” I said. We talked for a while. He was just back from rehab, he said. I asked for what, and he said opioids.

“And how are you doing?” I asked.

“Okay so far. You want a soda?” He offered me a Sprite, which I accepted.

It was cold and windy, and I had left my jacket in the car. I should have gone to get it but I kept hoping that any minute he’d invite me into his truck, which was warm enough inside for him to be wearing a T-shirt.

He didn’t. He liked to talk, I wanted him to, and it wasn’t long before he told me how he had let a guy live in his place for a spell while he was gone. Then, when he came back, he and the guy had gotten into an argument and the guy shot him. “Right here.” He showed me an ugly scar on his arm going up toward the pit.

An abandoned trailer, with Blanca Peak in the background.

The next day, bumping down a lonely road, I saw a small S.U.V. turn into a driveway, so I honked and followed it in. The driver saw me and slammed on the brakes; she wanted to know who I was. I got out and introduced myself. Two African-American women looked at me skeptically but then made the connection to Robert of La Puente. They signaled that I could follow them to their rickety mobile home.

The day was sunny and warm, and we gathered around the back of the S.U.V. while three dogs on chains snarled at me and the older woman told them to shut up. She was Rhonda Deffley, she said, and this was Ke’Attrice Stanley, her daughter.

Rhonda had hair going straight up from her scalp and an animated style of talking. She spoke of growing up in California and Chicago but eventually “burning out” on more populous places and coming here twenty-one years ago because, she said, “I decided I wanted to be a recluse.” Ke’Attrice, who was heavy, spoke of medical issues and “a problem that’s breaking our hearts.” An abandoned place nearby belonged to a woman named Juanita MacArthur, who had lived there even longer than they had—“a pioneer,” the women called her. Her husband had died a few years before. Recently she’d fallen, broken her arm and hip, and finally been discovered by the man who delivered her oxygen. She’d had to leave the prairie for an old-age home. And now, they’d heard, she owed back taxes—$585 and $166 on her land and house, respectively. “She was a founder” of the community, lamented Rhonda, who feared that now “it’s gonna be bought by an outsider.” I left them with a pile of wood.

The next day, I drove past a white-painted front fence without a gate and parked under an actual tree near three other cars, one with the hood up, its battery connected to a solar panel that rested on the ground. I stepped out and was thronged by four dogs, three of them blue heelers (a type of Australian cattle dog), a ranch dog popular in the area. Their owner, Paul Skinner, was an affable gay man in his fifties who said he had lived in his mobile homes (two of them joined together in an L shape) for more than twenty years. He invited me inside and made me tea. Raised in northern California, he suffered from a social-anxiety disorder and said he had found some relief on the prairie. He doted on “the girls,” as he called the dogs, and chatted happily about an annual winter trip out of the valley to escape the cold and especially the wind, the force of which, pushing through his windows and rocking his trailer, had lately started to make him anxious. He proudly showed me a form letter from La Puente, signed by Lance, thanking him for his recent donation of fifty dollars. He may have been a man of humble means, he said, but he had good values—including opposing President Trump, which he said put him at odds with many of his neighbors.

I complimented him on the two trees on his property—a rarity, I could already see. Paul explained that they’d survive on their own if you could get them past the first four or five years. He’d watered them several times a week to get them through the summer heat, and gradually their roots grew deep enough that they could keep themselves going. So they were a sign of constancy. (I would later hear an acquaintance say he’d pay several thousand dollars extra for Paul’s place, “just to have those trees.”)

Outside the Gruber house

A few days later I saw a sheriff’s car cruising slowly across the prairie and decided to follow at a distance. As the cruiser approached a property where a new house was going up, I saw a woman jump into a red truck and drive away quickly. The cops didn’t follow her, but they did pull into her driveway. My truck had La Puente signs on its doors; I used that cover to pull in after them.

Only one of the guys in the cruiser was dressed like a cop; he was actually wearing a bulletproof vest. The other one, shaggier and wearing a Denver Broncos jersey, was doing the talking. In the driveway listening was a man who had been working inside the new house. No, he was saying, he didn’t know about permits. The owner wasn’t there—she’d just remembered an errand she needed to run in town. Well, just tell her she’s got three days to come in and see us if she didn’t pull the permit, said the shaggy guy, and he didn’t think she had. He gave the construction worker a pamphlet with county building-code information. After I introduced myself, he gave another one to me. And then they left.

“So those are the code-enforcement guys?” I asked the worker. He nodded and told me that Jinx, the woman in the pickup truck, had very much not wanted to meet them because the permits—for a septic system, for a driveway—cost money and required expensive additions to the work plan. “But once you’re on their radar. . . ,” he said.

Matt Little and others at La Puente had warned me about this. Costilla County, where I was, had been particularly harsh lately with code enforcement. In the most extreme examples, code-enforcement personnel would show up, armed and wearing bulletproof vests, at a residence that had been built years before, issue the occupants a summons for not having a septic system, and give them ten days to put one in or face a daily fine of $50—though getting such a system installed takes two or three months at best. Robert of La Puente said several people had placed boards with nails in their driveways to discourage the unannounced visits.

Draconian enforcement had also energized a small sovereign-citizen movement, which the local police feared—and Robert did, too. I knew there was a road nearby where code-enforcement officers would no longer travel, because they had been shot at during a visit not long ago. One man in the area had, along with others, declared himself a “common-law marshal,” and on Facebook advised that it was time for people to “form your militias. . . . The time has come for the masses to rise.” (A promoter of the sovereign-citizen movement who had advised the Bundys in Oregon had heard about this “resistance” and spoken on a nearby one-lane bridge in October 2015.)

As it happened, the “common-law marshal” had since been charged with child abuse, as had his politically like-minded neighbor. The two were now in jail in San Luis. The first man’s family had left the area, but the second man’s had not. I knew they lived somewhere nearby, and the next week I pulled up to their place.

The Gruber family. Clockwise from top left: Frank, Stacy, Trin, Meadoux, Saphire, Kanyon, and Raven

It was the first dwelling I had seen that was totally without windows—basically a wooden box. In lieu of a regular doorknob and lock it had a hasp for a padlock that could be set when the occupants were away. Outside were some unchained dogs, including a scary-looking old white pit bull, but when I cracked open the door to my truck I could see their hearts weren’t in it. They started wagging their tails. A teenage girl came outside wearing a parka and slippers. I told her who I was but she wasn’t interested; she told me the pit bull had porcupine quills lodged in his face that they couldn’t get out. Also, he limped because last summer somebody had shot him in the leg. She ducked back inside to get her mom.

The mother told me her name, Sam McDonald, accepted my offer of firewood, and told her son, also a teenager, to come help me unload it. While we did, she confessed that, “My husband, he’s the one been charged with child abuse.” I told her I knew that and was sorry. She had four teenagers, including two girls I hadn’t seen yet, one of whom was disabled with a spinal deformity. “And you all fit in there?” I asked. Yes, she said, and the dogs came in at night as well. Her son slept in a reclining chair, and one daughter slept on the couch. She gestured toward what was probably the most beat-up minivan I had ever seen, and said, “Our biggest problem right now is that front tire.” It was flat and shredded. I asked if I could drive her or a kid into town with it, and she said yes, as soon as she raised a little money. I gave her my cell-phone number, and she asked if I might just spin back by in a day or two, since they were out of minutes on their phone. I promised I would.

As I drove away, I paused once to look back at the house. They lived just a five-minute walk from the Rio Grande canyon. Down by the water there were Indian petroglyphs. Beyond the canyon rose a gentle mountain. On all sides was golden grass. And they were surviving, it would seem, on thin air.

Maverick, a resident of the valley, in front of his Datsun camper

Frank had helped me set up my generator, and now my heat was slightly more reliable. But I’d still had to venture outside in the extreme cold of 2 a.m. to change propane bottles. Then, during night three, the last bottle ran out. I needed more propane, and I needed more gasoline. I could have also used a shower. And it was time to check in with La Puente and get more firewood. I drove into Alamosa.

Tona was easy to find in the homeless shelter, which she ran. I told her about my challenges keeping warm at night, and she suggested I get a Buddy heater—a small propane unit to keep me warm if the main furnace went off. I was sold on the name alone! Lance Cheslock had told me to be careful about using a heater that wasn’t vented to the outside, because of the possible buildup of carbon monoxide. But apparently Buddy heaters were quite efficient, and I knew my trailer was far from airtight.

I joined Matt Little for his weekly check-in with Judy McNeilsmith. He had a new story to tell, of trying to make contact with an extremely reclusive resident who, the only time Matt had seen him, discharged a shotgun into the air to show he was serious about wanting Matt to leave. Even so, Matt had persisted, returning every week or so to leave a small pile of wood and some of his business cards at the man’s gate. Matt told us what had happened then: “Come back around the next week and all my business cards are gone. Okay, so I left more wood. Next week I come around I get a note on a piece of paper. Says, ‘Thanks for the wood. Tom.’ I think, cool. So I continue dropping off wood, and the Tuesday after Christmas I got an envelope, says ‘The Wood Guy’ on it. Inside, on a Christmas card, it says, ‘Thanks for the wood.’ ” Matt still hadn’t met the man, whom he thought must be a veteran, but we agreed that this counted as progress.

Politics wasn’t discussed much around La Puente, and Matt never brought up presidential politics. He said he was nonpartisan. I knew he valued self-reliance, because he practiced it. Back in West Virginia, he’d told me, he’d hunt deer and turkeys for meat to feed his family. He agreed with Trump that food stamps should not be an ongoing thing for anyone. He disapproved of people taking government money who could get a job. But then he qualified that by saying that single moms are a special case: it makes no sense for them to get a job just to pay for day care they could do themselves. Speaking of job-seeking, he told me he thought the hoops the government makes applicants jump through are crazy: he had to attend a job-hunting seminar in Fort Garland. “The time and money I spent on that, I could have been out looking for a job.”

So it was interesting, a few days later, when the question of asking for help came up at a La Puente all-staff meeting. Once a month, around fifty staffers attend these meetings, gathering in a circle of folding metal chairs and old couches in the meeting room of St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Alamosa before work. Lance Cheslock is always there, but often he does not preside. Rather, he asks Tona or another trusted lieutenant to call on people from the various La Puente initiatives to offer a brief report and, if possible, a story. It falls to Matt Little, who is no fan of large meetings or public speaking, to report on rural outreach.

Though Matt is very much aligned with La Puente’s goals, his worldview differs from that of some of the other workers. He squirms when others refer to “clients” whom they “serve.” “They’re not my clients, they’re my neighbors,” he insists. And he dislikes the idea that he’s serving them. “Serving is what they do in restaurants,” he says. “I’m not serving, I’m just helping out.” His rough and dirty hands, dusty boots, and worn jacket make him stand out in the group at La Puente.

That week he told the story of a girl named Raven whose family moved out to the valley from Missouri after their house burned down. The place they moved into was a bit shy of the 600 square feet required by code, so Matt led a group of church volunteers who built an addition to the house. He had worked in construction for many years and so had been the perfect person to lead the effort.

Later in the meeting, one of Lance’s managers led a group-relations exercise. Everyone was asked to stand or sit, she explained, according to how they answered questions such as: “If you found yourself without money, support, or housing, would you ask for help?” Most of those present said yes, which was the answer the manager was after. “If you are not able to accept help without judgment, you are unable to give help without judgment,” she said. I thought that sounded reasonable. But Matt disagreed, quietly. I was sitting next to him. “No,” he muttered. “That was the exact situation I was in a year ago. I’ve got my gun and my tent and the woods, and I’m going to take care of myself. I like helping all varieties of people,” he said, “but the target I like looking for is the people who help themselves, which most of my people do.”

A road on the flats, what locals call the interior of the San Luis Valley

It would have been lonely living out on the prairie by myself. Crossing its undulations in my truck in the evening, I sometimes felt as if I were on an ocean, so long were the views. Distant lights from isolated trailers looked like bobbing dinghies, their survival precarious. I was always glad, at the end of the day, to drive back to Frank and Stacy’s and enter my little trailer. The vast surroundings made the humblest shelter—Tuff Shed, tent, cab of a truck—feel quite cozy. First to welcome me as I approached would be the dogs who swarmed my pickup, from slobbery, friendly Tank the St. Bernard to Little Bear the Chihuahua who, perpetually failing to recognize me, nipped at my ankles.

Then anywhere from one to four of the five daughters would knock on my trailer door to see how I was doing. They delivered pictures drawn with crayons and told me tales of what they’d seen on the prairie that day. The pair of ravens that perched on the wooden fences were so regular that the girls had named them Coo and Caw. Each farm animal belonged to one of them. Kanyon was very proud of Pumbaa, her potbellied pig, who would roll over for her to scratch his bristly stomach. They cackled when Goldie, one of the Nigerian goats, leaped into the back of my truck when I opened the rear gate to retrieve a bag of groceries or when they held up a container full of strawberry yogurt for the goat and his beard dripped pink. They reported on the latest bad word uttered by George the cockatoo.

Among their chores was feeding animals. This included the two horses of an elderly neighbor, Jack Brown, two miles away. Often Stacy or Frank drove the girls over for this chore, and a couple of times I went with them. Jack, a former truck driver from Nebraska, was a religious Christian. His place was bare-bones: a trailer, a shed, a truck, a pen for horses with a big roll of hay next to it. Sometimes, when the weather allowed, the girls would ride their bikes to his horses.

When I’d returned from a time away, they told me what had happened the week before. There were some hills between Jack’s place and theirs, but the girls were strong. The bikes were nothing fancy, and Meadoux’s lacked brakes, but out here that didn’t really matter . . . until that day: riding into a stiff headwind, they crested a hill and saw a small herd of pronghorn antelope resting just below. The wind was so strong the herd didn’t hear them, and some didn’t see them until it was too late. It was a fairly soft collision, from the sound of it: Meadoux said the pronghorn she hit bounded away as if nothing happened. Trin said, “I crashed my bike, but I wasn’t hurt because I was wearing my parka and I rolled.”

Though young, both girls were experienced with guns. Trin had her own .22 rifle, and Meadoux a BB gun; in season, they would accompany their dad elk hunting. At night they’d occasionally be left alone to babysit. They knew where the guns were, should they ever need them.

One day, when I told the two oldest I needed to take a walk and get some exercise, they offered to accompany me, along with their dogs, and two goats, on leashes. Trin, the oldest, taught me names for plants I knew only by sight: those were yuccas, these were chico bushes, that was a sage. And the girls identified things that were mysterious to me, such as the hoofprints feral horses left on dirt roads or holes where a ground-dwelling owl might live. I worried that they weren’t getting as much of an academic education as kids who went to school. But, thanks in part to the efforts of their mom, they were experts in the natural world around them.

Five years earlier, using settlement money from an accident she’d been in, Stacy had bought about thirty-five acres. Her idea was that this would be enough not only for a future home site but for each of her girls to have land to settle on. Three years later, using an inheritance from her estranged stepfather, she bought the mobile home. I knew that Trin and Meadoux were proud to live on the prairie but also that life for their family was very hard, with few creature comforts and a constant shortage of money. The girls appreciated trips to Denver to stay with their aunt, or even to nearby Antonito, where they could get a good signal on Trin’s smartphone. (Most places on the prairie had poor cell service.) They watched TV and knew what was happening in pop culture. When I shared a story on Facebook about New York City teens who had their own fashion sense, Trin was the first to like it.

Stacy at first was shy about inviting me into their mobile home because often it looked as though a hurricane had hit. But slowly the family became more comfortable with me. We had a few things in common: we were fans of the Denver Broncos, and we were readers. Frank loaned me a couple of solar panels and car batteries for my trailer and helped me wire them up. He helped me fix a flat tire on my truck and drew maps with his finger in the sandy soil to show me how to get to places I wanted to visit.

And yet . . . they loved guns and hated Hillary, while I felt pretty much the opposite. One night, after they shared a dinner of potato soup, we were all watching some YouTube videos of Casper, Wyoming, Stacy’s hometown, on TV. (Their solar power was usually ample enough to power the television, the refrigerator, and the lights.) I sat on the couch with an over-affectionate white boxer named Nae Nae and the blue heeler mix named, in a nod to Stacy’s ancestry, Lakota. Next to the couch was the parents’ bed, draped with other dogs, including the giant, filthy, slobbering St. Bernard, and at least three of the girls. I winced at the occasional ear-splitting shrieks of the cockatoo, but the family hardly noticed—they were much more comfortable with the chaos of life than I am. I make plans and then try to arrange my calendar and bank account and relationships so that I can carry out those plans. They live hand to mouth and don’t make many plans. They don’t believe in schools and formal education. They believe in weed and don’t drink. They are exiles, or self-exiles, while I am a city guy trying to fashion a bridge to the far margins.

A barn on a homestead in the San Luis Valley

Christmas and New Year’s came and went. After about a month on the prairie I returned to my life in New York—but I left behind the trailer, paid my rent each month ($50 when I wasn’t there; $150 when I was), and made three visits before May 2018, when I returned for the summer. I had missed the views and the space, the low density and the stars, and the quiet, as well as the people who felt at home amid a minimal number of other people.

Much had changed in a short time. Frank and Stacy and their family had moved about seven miles away to a property that had a small house and a well. They were buying it from another couple, who would remain on the property in a trailer. I was invited to relocate to a corner of the new land with them, and I did.

Jack had gifted Meadoux and Trin his two horses, which now were part of the family menagerie, as was a second St. Bernard, a female rescued from a home in Colorado Springs. Some of the ducks, chickens, and geese had made the move, but many more had died in the interim. Jack was not well and would soon be diagnosed with cancer. The McDonalds, the father still in jail awaiting trial for child abuse, were thinking hard about leaving the area before school started in the fall—possibly for Alabama, where they had come from years before. Another neighbor told me her cousin was visiting to withdraw from her addictions to meth and heroin. Paul was planting a garden and thinking of getting his last teeth pulled. Rick, also in the area, had sent out a group message on Facebook warning of the mountain lion he had seen on his property. Rhonda and Ke’Attrice, before long, would report that Rhonda’s house had been robbed while she was away; disillusioned, they said they might put it up for sale and move to Alaska.

At La Puente, Matt was spending less time introducing himself to new people and more time responding to the requests of those he’d already met—his client list (though he’d never call it that) had grown by word of mouth. Months before, he’d bought ten acres at the foot of Blanca Peak for $8,500.

I drove up to see him at his new place on a beautiful afternoon with a warm sun and a moderate breeze. The gigantic sky above had room for several weather systems: to the east it looked like storm clouds, overhead it was high cirrus, and a different situation that had not quite declared itself was manifesting over the San Juans to the west, where most of the valley’s weather came from. To me that sky said, Wherever you are, you are not stuck. There’s a different situation, new possibilities, new weather, a short drive away.

The amazing thing was that a person, even a person of very limited means, could actually buy a piece of these vast acres of land—some of it farmland with pumped irrigation but most of it just undisturbed, primeval—for not too much money. Not that this would be a smart investment in terms of return: Paul had told me he’d paid about $2,300 for his five acres twenty-five years ago, which was probably close to what it was worth today. “But you know what they say about land,” he said. “They’re not making any more of it!” The lots are now mainly sold online, on the sites that pop up when you search for “cheap land Colorado,” as Matt and many others had done. It is even sold on eBay, where one serial seller maintains that the location of a particular lot doesn’t make much difference: “There are no rare finds here, it is all the same views, sage brush, same rattlesnakes.”

But to me these lots are not all the same. A few of them had neighbors visible, and you wanted to size up neighbors. A few have been occupied before and have junk left on them. A few of them are situated near enough a cell tower that you’d get more than a single bar of signal. A few are near a road that might see several cars a day (with the associated dust). I thought about these things and about where I might like to buy. I couldn’t entirely explain why: I wasn’t going to move out here, and it wasn’t my wife’s idea of a nice vacation property. And yet, and yet . . .

Matt was starting to build his new home. It was on a piece of land where, almost certainly, nobody had ever lived (though someone may have hunted or grazed animals there). He had machinery, in particular his truck; he’d dragged a heavy tow hitch from a neighbor’s mobile home to clear a driveway through the sagebrush. But now, to prepare the ground for laying blocks for the shed he’d ordered, he was using a shovel. He paused when I drove up and sounded so proud when he laid out his vision: The corral would go here. His La Puente pickup and his own Ford F-150 would be parked over there. Trash pit yonder. The equipment had changed from the 1900s, but the motions were essentially the same: Matt was a homesteader, with all the beauty and promise and drama and uncertainty that implied.

We hung out for a while and then I headed back south. As the sun began to set, the prairie grasses took on a golden glow. There was an old-timer I’d met and liked whose neighbor’s place was for sale. It had a well on it, and a septic tank, and a trailer in pretty rough shape. The owner felt it was worth $20,000, but the old-timer opined that “out here, it’s worth what somebody will pay.”