It’s forest fire season in Oregon. Yellow smoke fills the valley. I can’t see the mountains, can’t see across the street. My neighbor says, Don’t worry, the fire’s still thirty miles away.

For weeks, my small town has been blighted by a thick, toxic smog. There’s a government advisory to remain indoors. Like everyone else, I’m going a little crazy. I decide to risk a walk. On Main Street, people are window-shopping in particle masks. For a moment, I can almost pretend the smoke smells like bacon or toast. Really it smells like war.

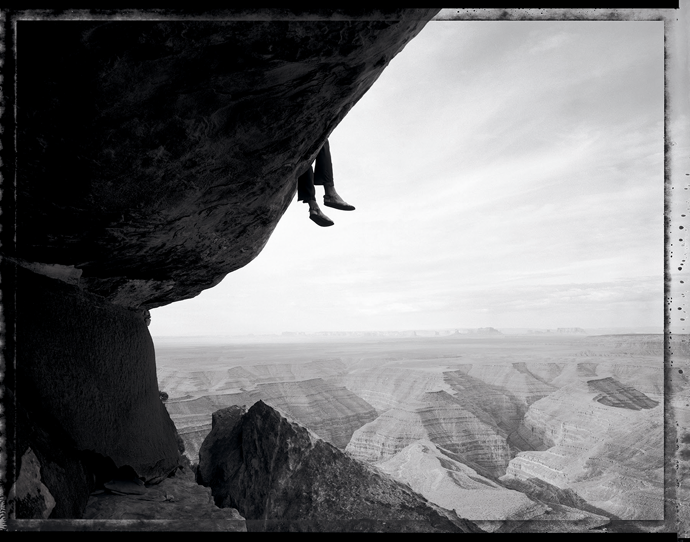

“Contemplating the View at Muley Point, Utah, 1994,” by Mark Klett © The artist. Courtesy Etherton Gallery, Tucson, Arizona

At the food co-op, I order a coffee and bravely take a table outside. I write in my journal: 8 a.m., July 25, 2017. I’m ready to report on the disaster, describe the burning forests, the end of the world.

Then, through the smoke, I see a boy begging in the parking lot—a placid teenager holding a book in one hand and a sign in the other.

The sign says: i love you.

He’s sitting in the dirt at the edge of the lot. I walk over and offer him a five-dollar bill. He has troubled skin, glitter-green eyes. There are leaves in his dark hair. He takes my money and smiles. “Thanks,” he says—and for some reason tells me his name. “I’m Donny.”*

He’s reading Ram Dass. Be Here Now. I tell him I read that book when I was sixteen. Donny might be sixteen. He says, “I’m reading his book on dying next,” pausing to add, “My mom just died.”

“I’m sorry,” I tell him.

When he smiles again, showing his crooked teeth, I reach in my pocket to give him more money.

“No,” he says. “That’s okay.” He stands and gives me a hug. Only then do I realize he’s wearing a pink negligee and nothing else. His bare feet are filthy.

I ask him where he sleeps.

“The woods,” he says.

“With all this smoke?”

“It’s not so bad.”

I reach for a twenty, tell him, please, to take it. Tell him to be careful.

He accepts the money, holds the bill to his negligee as if he’s pinning on a corsage. As I walk away, he calls out, “Sir, I love you.”

Forty-five years ago, I was the boy in the woods, my long blond hair tangled and full of twigs. I was homeless—though I never would have used that word. In my high and lilting voice, I would have said, “The mountains are my home.” I had left my parents and siblings behind, for many reasons—including the fact that, like Donny, I was fond of negligees and dresses. One Saturday, when I was eleven, I’d been caught in drag. My mother laughed, but my father was furious. Sneering, he said, “The boy is a goddamn queer.”

Soon I was sent away.

After unsuccessful stints at two boarding schools—one run by monks, the other by bohemians—I was shipped off to live with my sister Donna, in California. My mother thought my married Christian sister would be a good influence. She had no idea that Donna was running drugs, or that part of her hippie Christianity involved the use of psychedelics, which I soon learned to call sacrament.

My sister distributed sacrament all across the country. A pretty blonde who read the Bible as she flew LSD to Boston and New York, Donna believed she was doing God’s work. “Love and acid will change the world,” she told me. My sister was deeply stoned, and deeply kind. I adored her, and I believed every word she said.

When she traveled on her runs, I stayed behind with her husband, Vinnie, a bearded man in white clothes who, on a good day, looked like Our Savior. One night, Vinnie had that peculiar sway that came over him when he double budded—a joint and a couple of bottles of Budweiser. Outside our bungalow, he put his arm around me and said, “You know, Chris, there’s nothing wrong with you.”

“Okay.” My cheeks were red.

“I know about you, Chris. Your sister does, too. We prayed, and Jesus said it’s fine. What you are.”

Not long after this, my sister had a baby, and she and Vinnie couldn’t really take care of me anymore.

I ended up on my own, wearing a backpack, looking for God in the high mountains. Through my sister, I had made some friends—connections—and as I traveled about I survived by selling sacrament, ingesting a great deal of it along the way. As a teenager, I wandered the West for several years, alone—half desperate, half ecstatic, always looking for God. As my world burned down—no home, no family—I tried to stay true to what my sister had taught me: love and acid.

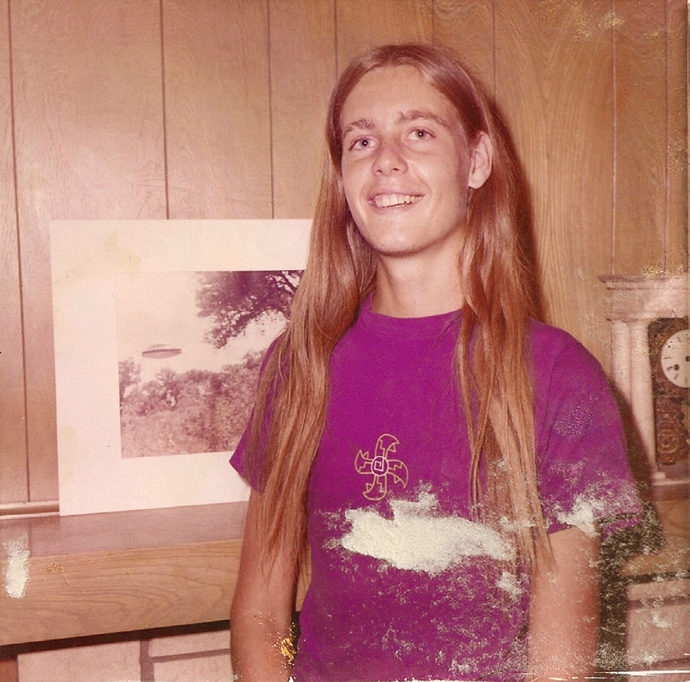

Chris Rush in California, 1973. Courtesy the author

By September of ’74, I had turned eighteen. At six foot two, I weighed 125 pounds. I was getting a little worn out. After a long hot summer, I found myself stranded outside Twin Falls, Idaho, hitchhiking in short-shorts and purple sneakers. Rednecks chucked beer bottles at my head as they drove by. I had to get out of there. Standing on the side of the road, I closed my eyes and tried to visualize the perfect ride.

When a car finally pulled over, it almost hit me. The driver, a blond kid with a bowl cut, could barely see over the steering wheel. He waved, as did his buddy, an American Indian with the same tragic haircut. They were incredibly young—tiny, skinny things. I put my gear in the back seat and asked where they were headed.

“Wherever you want to go, man. We don’t fucking care.”

“Don’t you have school?”

“Nah, we’re just driving around.”

“Enjoying life,” the other said, solemnly.

I said, “I’m thinking of going to Arizona. But you’re probably not going that way.”

The blond one said, “If you pay for gas, we’ll take you anywhere.”

I love you, I wanted to say. But I deepened my voice a bit and said, “Okay then, let’s go to Arizona.” I told them my name was Chris.

As the car swerved back onto the blacktop, the driver introduced himself as Raymond James (“But call me Ray”)—and, gesturing toward his slightly taller companion, “That’s Tony.” Despite the boys’ jitteriness and the terrible driving (neither seemed old enough to have a license), I felt safe in the tiny brown Datsun—not least of all because of the bumper sticker I’d noticed when the car pulled over: warning. protected by jesus.

“Are you guys Christians?” I asked.

“No,” Tony said. “We’re nothing.”

“Why do you think we’re Christians?” Ray said, eyeing me suspiciously in the rearview mirror.

“I don’t know,” I said quietly, not mentioning the bumper sticker. “You just seemed nice.”

Hitchhiking was always a blind date. A car pulled over and you looked for clues. Drunk? Stoned? Crazy? But it was my only option for getting around, so I made an effort not to worry, despite a nasty episode in New Mexico, where I’d had to jump from a speeding pickup and nearly died.

I couldn’t live in fear forever. Fear was the reason I’d escaped New Jersey, escaped my father. On the road, I’d taught myself to be patient and positive, sipping water and watching the sky. I sang pop songs and ate sunflower seeds one at a time. I also bit my nails.

Often, I’d end up waiting on a patch of pavement outside some town, already piled up with hitchhikers. I studied my peer group—a tribe of lost children. Sometimes older drifters would pass by, men with only the clothes on their backs, maybe a bedroll across their shoulders. They moved lightly across the land, always flickering just out of frame.

I remember the day a truck picked me up in the rain, and then stopped for a drifter just down the road—an old man in a ragged dinner jacket. The geezer sat up front with the driver and me, saying nothing, just rolling cigarettes and smoking. His face was a worn wooden mask, like nothing I’d ever seen. It frightened me. I could feel the cold on him, the tremor. It was like he’d been outside forever. After an hour or so the rain stopped, and he asked the driver to pull over.

After he got out, he stood on the shoulder of the road and bowed to me, deeply, reverently, storm light flashing in the distance. The image was burned into my heart, and the message that came with it: once a boy, now a beggar.

In the back seat of Ray and Tony’s Datsun, I offered a silent prayer. Getting a single ride from Idaho to Arizona was a kind of miracle. In celebration, I rolled a joint from my survival stash. As we got high, I mused on the many places we could visit on our way to Tucson. Arches, Grand Staircase, Zion. Describing the splendor of these locations, my voice went up to its normal register. The boys only nodded, not rising to my level of enthusiasm. I asked whether they’d ever left Idaho before.

Ray snickered. “Nope. But good fucking riddance. We hate this place.”

Soon, Idaho was gone, and we were rolling into the parched plains of northern Utah. The road was excellent, but Ray continued to drive terribly, drifting from lane to lane at high speed. After the sun set, when the headlights seemed to be pointing toward our certain death, I suggested we pull over for the night.

We parked in the desert. The boys slept in the car while I crashed outside, on the dusty earth, comforted by my sleeping bag and a piece of blue velvet I’d stolen from my mother’s sewing room.

The next morning, I shared what food I had. The boys had never seen granola before, but they sucked down every crumb. It seemed that they hadn’t eaten in a while. In the light of the new day, I noticed that they were wearing identical jeans, sneakers, and white T-shirts—all quite dirty. I began to entertain the idea that perhaps they were not the rightful owners of the Jesus-protected Datsun.

As we traveled south, I tried to play the detective, casually asking Ray, “So, how’s your gas mileage?”

“What’s that?”

“How much gas do you use?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, it’s a nice car, man. What did you pay for it?”

“His mom gave it to him,” Tony said.

“Yeah, for my seventeenth birthday.”

Ray was clearly not seventeen.

That morning, we’d finished my granola, as well as my seeds and dates and crackers. We needed provisions. Approaching Salt Lake City, I told Ray to pull into a shopping center, suggesting we pick up a few things to eat. The boys said they’d wait in the car.

After weeks in the woods, pushing a shopping cart around a supermarket was bizarre—the muzak and bright lights jangling my brain. Of course, I remembered what my hippie sister taught me, and I tried to buy only healthy food: nuts and berries, carrots and apples.

The checkout girl, a sweet-faced kid with a wedding ring and lacquered black hair, was perplexed. She asked if I was some kind of vegetable lover.

“Actually, I’m a vegetarian.”

“Really? I’ve never met a vegetarian. I would just die without meat. I’d bite someone’s leg!” she screamed, laughing at her own wit—red lips and sharp teeth. She told me to have a blessed day.

“Always,” I said.

In the parking lot, a hole opened in my chest: the Datsun was gone. Everything I owned was in the back seat, including my drugs and the stash of cash in my pack. I ran around the parking lot, though I knew it was hopeless.

I sat on the curb and cried. Then, instead of crying, I prayed. An hour later, a brown Datsun pulled up in front of me.

“Hey fella, wanna ride with uth?” Tony said, with an exaggerated lisp.

Ray was now wearing gigantic aviator sunglasses. The mirrors covered too much of his face, leaving only his upturned nose and a tight smirk too small for the cigarette in his mouth. Tony was making kissy sounds in my direction. After a few seconds, they began to laugh like lunatics—huc . . . huc . . . huc! I was so grateful for their return, I allowed myself to smile at their mockery. Anyway, I had learned early how to distinguish dangerous mockery (my father) from the kind rooted in nervous confusion (my brothers).

Back in the car, I tried to be diplomatic. “So where’d you guys go?”

“We needed cigs.”

“Where’d you get ’em?”

“Stole ’em.”

“And those glasses?”

“Same.”

I kept my mouth shut as the boys hummed along to the radio and chain-smoked. They kept smiling at each other, some sort of telepathy passing between them, while I studied Utah out the window. It was a hitchhiker’s hell. Ten miles out of Salt Lake City, we were back in the wastelands. I couldn’t get out of the car now—not here. Later, at a gas station, we filled up the tank using my cash. When I went to use the bathroom, I took my pack, half hoping the boys would be gone when I came back, and then shakily relieved to find them still there.

“Hey man,” Ray said, once we were driving again, “what kind of food did you get us?”

In the back seat, I made peanut butter sandwiches and handed them to the boys, along with an apple each—a children’s lunch. Afterward, I thought to light another joint, but I was uneasy. My hands trembled. This happened now and then on the road—a dizzying anxiety. Where am I? Where are the people who love me? At that moment, I missed my sister Donna—someone who could guide me, tell me what to do.

As we flew down the highway, the radio played country and western—way too loud. Suddenly I couldn’t take it. I screamed, “Shut that shit off!”

The boys looked surprised by my outburst, and Tony switched off the radio.

“Pull over,” I said. “I’m getting out.”

Ray swung onto the shoulder of the road—a stagecoach careening in a cloud of dust. The car stopped at a ridiculous tilt, half in a gully. We were all silent. I caught Ray’s eyes in the rearview. He looked scared, and somehow it stopped me from jumping out of the car. I felt his eyes were asking me for something. But before I offered anything, I needed the truth.

“Whose car is this?” I said. “If you want my food and my money, tell me what’s going on.”

They looked at each other, with their twitching telepathy.

“It’s not our car,” Tony said.

“No shit.”

“We stole it a week ago, from some chick.”

“There was food in the back seat,” Ray said. “We were starved, man.”

The boys’ breathing changed. Their look of desperation—something I understood—was a kind of relief. After nearly a minute of silence, Tony spoke quietly.

“We were in Snake River juvie. We ran away.”

Ray had tears in his eyes now. “They beat us, man. You don’t know.” He looked at Tony. “We’re best friends. We’ve known each other since kindergarten.”

Their faces went slack, and in their torpor, I could clearly see how young they were.

“We went over the fence in the middle of the day,” Tony said. “They didn’t even chase us. I don’t think they even fucking cared.”

“So no one’s looking for us—if that’s what you’re worried about.”

“I’m not worried,” I said.

“It’s not our fault some stupid chick left her keys in the ignition. The car’s a piece of shit anyway. We did her a favor. We’re doing you a favor.”

“And why were you in jail?”

“Juvie’s not jail,” Ray said, but Tony rolled his eyes.

“Well, not exactly jail,” Ray amended. “Besides, all we did is steal some shit. Honestly.”

“And how old are you really?”

“Fourteen.”

“Both of you?”

Ray nodded.

At fourteen, I’d stolen paisley scarves from Bamberger’s, not cars. And though I’d never been physically beaten like these boys, I did know what it felt like when someone wanted to crush you. My own face twitched, and when the boys looked at me, I felt I was included in their telepathy.

“Fine,” I finally said. “I’ll keep buying gas and food, but from now on I’m driving. Give me the keys.”

Arizona was still seven hundred miles away, and I wanted all three of us to arrive in one piece.

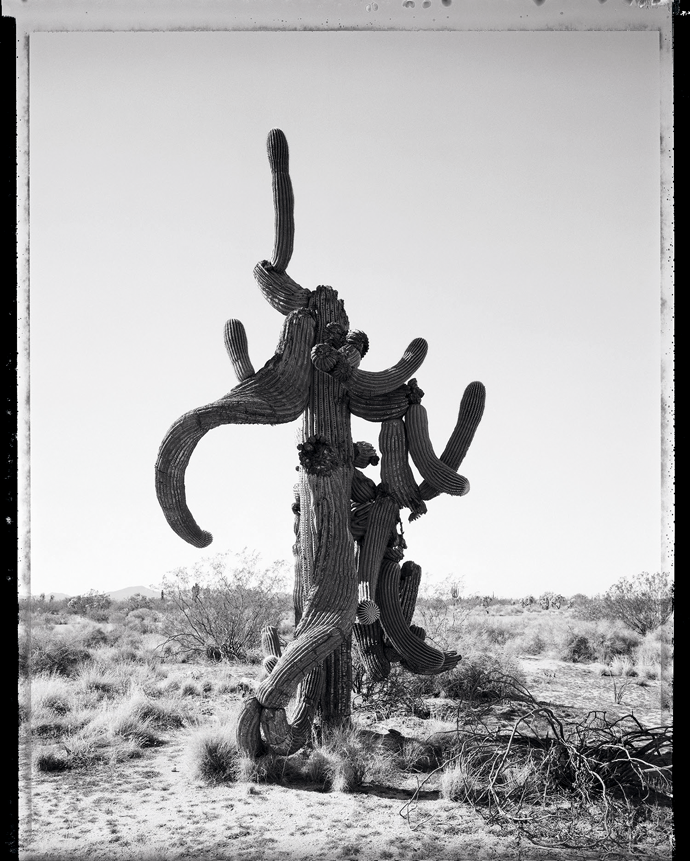

“No. 5-9 1,” from the Saguaros series, by Mark Klett © The artist. Courtesy Etherton Gallery, Tucson, Arizona

My taking over the driving was a relief for all of us. I had a license and could see over the steering wheel. The boys’ confession was a relief, too—at least for them. They turned into goofy kids, throwing raisins at each other in the back seat. They threw a few at me, letting me in on the joke. We were co-conspirators now. The vibe relaxed. I picked a raisin off my lap and told the boys not to waste food.

That night, in my sleeping bag, I considered the situation. Under desert stars brighter than God, I knew that driving a stolen car with fourteen-year-old fugitives was somewhat insane. But I wasn’t afraid. I was a homeless drug dealer who lived in a tent; I could manage this.

Besides, I really wanted to get to Tucson. I’d spent time there, had a few friends, maybe a place to stay. The guy who sold me acid lived in Tucson, the man my sister used to work for.

Driving, I tried not to think about the woman whose car this was, the interior now full of soda cans and trash. At the next gas station, I made the boys throw out all their crap and wash the windows. I studied the map, and at all times kept control of the keys.

We’re on an adventure, I told myself. We’re helping each other. Living so long with hippie dealers, I understood that a person’s spiritual evolution sometimes required a measure of illegality.

The idea came to me that I might be a good influence on the boys, the way my sister had been on me. Tony and Ray, kids who’d been beaten in juvie, were about to enjoy a trip through the national parks. As soon as we got to Tucson, though, I’d probably ditch them. My thinking was somewhat elastic.

I rolled joints, kept things moving. But when the boys got high, they were unpredictable. At one point, red-eyed Ray set the ashtray on fire, melting the dash. His laughter reminded me of my little brother Steven, and that was comforting.

Tony, on the other hand, only grew more sullen with each hit. One stoned night in the desert, he asked who I was, what I was.

I said I was a human being on planet Earth. I asked who he was.

He said, “Oh, you’ll figure it out,” and spit.

The boys didn’t tell me more about their lives, and I kept my mouth shut as well, never mentioning the problems with my family. I also didn’t mention that in addition to the reefer I had a couple of hundred hits of acid in my sleeping bag.

Drifting onto the plateaus of southern Utah, the earth went red. Canyons opened in rusty sandstone, the rock worn wobbly like a great melted city. Every time we pulled over, I stopped and stared, trying to comprehend this otherworld of stone towers, of bridges to nowhere. The boys smoked cigarettes and seemed bored.

On day three, I drove toward a remote waterfall, a tiny name in a corner of my Rand McNally. At the end of a long dirt road, I parked. The Bureau of Land Management sign said: lower calf creek falls—3 miles.

The trail was long and dusty. The boys complained every step of the way. I promised them that we’d be swimming soon. When the waterfall came into view, we all fell silent. From a notch in an immense red wall the river launched, a glittering braid a hundred and twenty feet long. The three of us ran toward it, as if the water might suddenly disappear.

From a grove of cottonwoods, we watched the waterfall sway like a mad ghost, hissing as it plunged into a deep, round pool. I stripped and dove right in. The water was shockingly cold. I climbed out, gasping like a shipwreck survivor. Despite my encouragement, neither boy would go into the water.

After lunch, I pulled some LSD from my pack—Blue Windowpane, perhaps the strongest acid in America. By this point in my life, I’d dropped over three hundred hits of acid. My sister and her friends had first given me LSD when I was twelve. Later, I’d given it to my little brothers when they were fourteen and fifteen. I was taught to believe that acid was a gift, a teaching. Maybe Tony and Ray needed it. They seemed confused, sad.

I wondered what my sister would say—whether her thinking had changed. I’d always imagined Donna and me tripping together forever, but the last time I’d spoken with her, she and Vinnie were living on a Christian commune down south, and she was very unhappy. The food was gross, she said, and their bathroom was nothing but a hole in the ground. There were wild dogs lurking in the woods. “How am I supposed to toilet train a child in a situation like this?”

That conversation had worried me. Was our glorious experiment of love and acid starting to fail?

I looked at Ray and Tony. They were screaming and throwing rocks at the water, like they wanted to break something. I decided not to give them any acid. I placed a hit on my tongue and put the rest away. The tiny cube of blue gel quickly dissolved and, within five minutes, I was trembling uncontrollably. Taking Windowpane was like being electrocuted by heaven.

I leaned back, closed my eyes, gave in. Soon, I was overwhelmed. My body was hollow, the emptiness lit by spark, my heart echoing in a great cavern.

The boys, assuming I was taking a nap, eventually did the same. We all lay under an ancient tree. For several hours, I listened to the waterfall, the rush and gurgle arriving from a distant galaxy. In the late afternoon, I sat up and saw the boys standing in a shallow part of the pool, pants rolled up, afraid to go in past their knees. I went over to them.

Tony took one look at me and asked, “What’s wrong with you?”

Ray just said, “Can we leave?”

I ignored their questions. I was in ecstasy—such love in my blood, my worries forgotten. My companions seemed miraculous, shivering on the coral sand, glowing. I remember the moment perfectly—the boys wavering, holograms in a ray of sunlight.

“Can we please go?” said Ray.

“You have a place we can stay in Tucson, right?” asked Tony.

“Sure,” I said—sure of nothing at all.

The next morning, in the tiny Mormon town of Page, Arizona, we washed our clothes. My companions, of course, had only the clothes on their backs. Standing in the laundromat, a shirtless, barefoot Ray turned to me. “So what’ll we do when we get to Tucson? What’s the plan?”

“Oh,” I said. “We’ll figure out something.”

These boys were relying on me—but really I had nothing to offer.

I didn’t mention that sometimes, in Tucson, I’d sleep in an abandoned house, on a concrete floor. In the mornings, I’d wake up covered in sweat, breathless from the heat. I knew something was wrong with me. Boys don’t spend years in the desert looking for God. They get jobs, get married, live in lovely homes. They do not hide in crumbling buildings. They do not masturbate with suntan lotion found in the trash.

Often, I tried to play my own movie backward—to figure out how I ended up alone. I’d abandoned everything for sacrament. Ran away to the mountains to pray. Sometimes it seemed so ludicrous.

Ray was still looking at me in the laundromat, waiting for me to explain the plan.

“Do you want these?” I said—holding out a pair of clean underwear. It was all I could think of to give him.

Blushing, he went to the bathroom to put them on.

Later that day, we visited the Grand Canyon. It was beautiful, of course, but too hot, too crowded. As we walked the Rim Trail, tourist families swarmed around us. Sun hats and cameras, crying kids scooped up by their mothers. Ray and Tony and I grew morose. We clearly didn’t belong there. Plus, I was still crashing from the acid trip. Everything was going sad.

The last night before Tucson, we camped in the pines, somewhere past the edge of the Grand Canyon. To celebrate, we got drunk on warm Coors. Above us, an Arizona sunset erupted in bloody shades of red. I knew it was a bad omen. The next day was agony, driving through the desert, the scenery sharp and unkind. In the back, Tony was agitated, kicking my seat and poking my shoulder. He kept asking me: “How long?” Ray was the opposite, dead quiet, with a look of worry on his face.

I knew I had nothing for these boys—no bed, no refuge, no clues. I could barely take care of myself. I knew I’d have to ditch them. Still, I felt rotten about betraying my new friends. On the freeway, past Phoenix, I began to feel sick. I watched the saguaros ticking by.

Then, in the rearview mirror—flashing lights.

Oh fuck! The speedometer said 90. Slowly, I pulled over, thinking: Where are the drugs? Where are the drugs?

The officer, obese and out of breath, took his time getting from the patrol car. I handed him my license and whatever papers were in the glove box.

“We were in a rush,” I said stupidly. “I promise we’ll slow down.”

The officer nodded and went back to his car; he was on the radio a long time. The boys were silent. When the cop returned, I prayed he’d just give me a warning.

“Everyone out of the car!” he yelled. He made us lean against the doors while he patted us down. “Mr. Rush, the car you’re driving is stolen. Did you know this?”

“No, sir. These guys picked me up hitchhiking. I volunteered to drive, that’s all.”

The boys were already in tears. Soon the cop had them in handcuffs, in the back of his car. The officer asked me for the keys to the Datsun. He searched the vehicle, but showed no interest in my backpack.

Under the front seat he found a very large knife. He showed it to me, before securing it in the patrol car. He came back with my I.D.

“Mr. Rush, your traveling companions are wanted on a variety of outstanding warrants. Seems they assaulted someone in Idaho, someone not expected to live. You are lucky to be in one piece.”

I felt bloodless, dizzy.

“I ran your driver’s license,” the officer said. “You’re clean. What’s about to happen to those two will not be pleasant.” He shook his head, looking weary. It was over a hundred degrees in the afternoon sun. “You have one minute to disappear from my sight.”

I was stunned.

He said, “I’m not kidding. Go—now!”

I scrambled through the car, retrieving my gear. Then I asked the cop if I could say goodbye to the boys.

“Hurry!”

Hands cuffed behind their backs, the boys were still crying. Ray looked up at me, shaking uncontrollably. “Don’t leave us,” he said.

Just then, five cop cars screeched onto the scene. I told the boys I was sorry and fled into the desert.

Journal entry: September 7, 2017. Heavy smoke. Mountains invisible. The forests are still burning. Many locals have left town. Not me. And not Donny. Now and then, I still see the beggar boy, working the parking lot. He always waves when he sees me, and occasionally I buy him a sandwich. In addition to his pink negligee, which has started to fray, Donny has two other outfits—a yellow smock with embroidered daisies and a no-nonsense tunic in gray.

Sometimes, after I hand him his sandwich, we chat. He’s shy, but after a while he tells me things. Military school, methamphetamine, hard father, hard drugs . . .

Listening to his story, I find my hands shaking like they used to, when I would stand at the side of the road, hoping for hope. Donny’s story is too much like my own.

Sometimes, as he talks, I feel a slow-rising anger in my chest. Donny says he’s been praying to the Goddess about the smoke. He tells me about a toothache, that he needs to see a dentist—but, later, when he finally has some money, he buys a dog instead, a big yellow mutt who will surely need a lot of food.

Stupid boy, I think. Does he not realize how reckless it is to live the way he does? I want to tell him how many times I’d almost died during my years on the road. I’m appalled by Donny’s ignorance, his innocence.

But then I see his sign. i love you. The cardboard is worn now, smeared with dirt and grease. Looking at it, I know something about this boy, and about the boy I once was.

When I finally got off the road and off drugs, at twenty, I crashed hard. I had overdosed and was sick for a long time. Trying to make a new life for myself, I was completely confused. I struggled to live inside a house and not go crazy. My father was still a tyrant, still terrified me, but my friends were kind, encouraging me to go back to school. I was too tired and ashamed to imagine anything like success, but eventually I got my G.E.D. and then found my way to art school. I lived a few different lives after this: jewelry designer, then painter, then writer. Most people never knew that I’d spent years living in the dirt.

I often wonder what would have become of me, as a teenager—what would become of Donny, for that matter—without our secret weapon, our ray gun of love? What if we’d looked at the world as it really was? Surely, we’d have found only despair.

Love and acid. It may have been a lie—but somehow my stupidity, my innocence, protected me. Maybe it would protect Donny, too.

One morning, in late September, the smoke is especially bad. I’m wearing a particle mask now, and when I walk to the co-op I bring one for Donny. But he and the yellow dog have disappeared, as I knew they eventually would. I walk over to his spot at the edge of the parking lot, see his footprints in the dirt.

A week later the rains come. The fires, after months of destruction, are vanquished. There is little feeling of celebration in town, only exhaustion and a quiet mourning over the loss.

“So many trees,” a woman says to me at the co-op. “We won’t see them again—not in this lifetime.”