About fifteen years ago, my roommate and I developed a classification system for TV and movies. Each title was slotted into one of four categories: Good-Good; Bad-Good; Good-Bad; Bad-Bad. The first qualifier was qualitative, while the second represented a high-low binary, the title’s aspiration toward capital-A Art or lack thereof.

Photograph by Marina Font, from the series El Peso de las Cosas (The Weight of Things) © The artist. Courtesy Dina Mitrani Gallery, Miami

Some taxonomies were inarguable. The O.C., a Fox series about California rich kids and their beautiful swimming pools, was delightfully Good-Bad. Paul Haggis’s heavy-handed morality play, Crash, which won the Oscar for Best Picture, was gallingly Bad-Good. The films of Francois Truffaut, Good-Good; the CBS sitcom Two and a Half Men, Bad-Bad.

Other titles inspired more debate. Were the screwball comedies of the Thirties and Forties Good-Bad or Good-Good? Their farcical plots indicated the former, but the witty repartee of His Girl Friday and Bringing Up Baby seemed to earn them inclusion in the latter category. Trickier still were titles that failed in their highbrow ambitions but succeeded, accidentally, as camp. Where to place Donnie Darko, a film that reached for profundity and fell on its face, offering instead the fun of pulp sci-fi? It was here—usually about five beers in—that our reductive system unraveled, prompting the suggestion of an additional preliminary qualifier. (Might Donnie Darko be Good Bad-Good?) My roommate and I caught a lot of sunrises that year.

We had time on our hands. We were twenty-two years old, living in Austin, Texas, and loosely employed; we shared a gig spinning a giant orange arrow outside open houses. Our artistic ambitions were grand but in flux. One week we might make headway on a screenplay, while the next we’d brainstorm names for a psychedelic jug band. We saw ourselves as the spawn of Richard Linklater’s Slacker, a pretentious art film that we agreed was Bad-Good. It was 2004, and though we’d been told that irony had died on 9/11, it appeared to have been resurrected in the hipster aesthetic that paired Nineties ennui with the stylistic hallmarks of Eighties kitsch: spandex and synthesizers, neon everything. This was useful; irony allowed for the guiltless consumption of the lowbrow pop culture we adored. There was a lot of it, especially on TV, where shows like The O.C. epitomized Good-Bad.

TV that aspired to Art was less abundant. For us, it existed in the form of DVD box sets of recent HBO dramas. There was the prison series Oz, which offered both a critique of the justice system and an abundance of frontal male nudity. There was Six Feet Under, a radically morbid family saga set at a mortuary. There was The Wire, the recovering journalist David Simon’s sociological epic of Baltimore’s drug gangs. And there was The Sopranos.

Much has been written about The Sopranos. This year marks the twentieth anniversary of its premiere, which has prompted a wave of nostalgia culminating in The Sopranos Sessions, a hefty compendium of episode recaps and interviews with the show’s creator, David Chase, in which authors Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall build a case for the series as sui generis artifact, the prestige drama’s Rosetta stone.

Such superfan gusto is nothing new for either critic. Seitz, who covers TV at New York, published a similarly gushing companion to Mad Men in 2015, and he cowrote another compendium with Sepinwall, TV (The Book), which might have more accurately been called TV (The Listicle). Sepinwall, a prolific blogger, is additionally the author of books about The O.C. and Breaking Bad, as well as 2012’s The Revolution Was Televised: The Cops, Crooks, Slingers, and Slayers Who Changed TV Drama Forever, which along with Brett Martin’s Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution, helped to propagate the consensus that The Sopranos and a handful of other series had ushered in a Golden Age of Television—the medium’s second or third, depending on who’s counting—during which the TV drama became America’s dominant form of narrative art.

There’s contention over its exact end date, as well as over the causes of its expiration, but critics agree that this Golden Age is over. We’re now living in the era of what FX’s CEO, John Landgraf, famously dubbed “Peak TV”: a surplus of scripted series—up from roughly two hundred to five hundred in the past decade—few of which appear to have the heft or cachet of The Sopranos and its ilk. But what exactly was the Golden Age? Critics such as Seitz, Sepinwall, Martin, and The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum are fond of the word “revolution,” likening the period to the independent film wave of the Seventies, which saw the emergence of American directors like Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese. HBO’s former CEO Chris Albrecht once compared it to the Renaissance. (He, by his own reckoning, played Medici.) I’d contend that the Golden Age was as much a triumph of branding as it was an artistic zenith, and that The Sopranos didn’t spark a revolution so much as open the door for a few truly innovative series and a lot of overpraised Bad-Good TV.

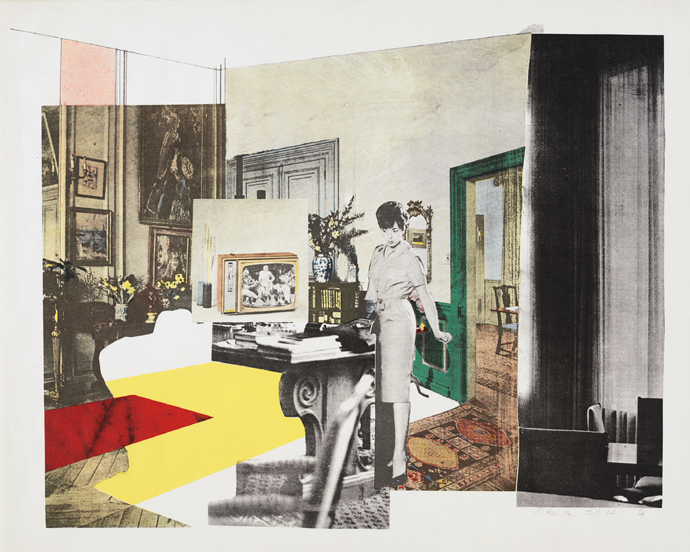

Interior, 1964, by Richard Hamilton © 2019 The artist. All rights reserved, DACS and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City/The Museum of Modern Art/SCALA/Art Resource, New York City

I’ll come back to The Sopranos, but first I want to discuss Bad-Good, an admittedly inelegant term for what the critic Dwight Macdonald called Midcult, which is not particularly elegant either. In his seminal 1960 essay “Masscult and Midcult,” Macdonald coined the word Masscult to describe popular forms—romance novels, Victorian Gothic architecture, the illustrations of Norman Rockwell—which he refused to dignify by classifying as culture. Macdonald’s chief concern was protecting high culture from the degradation of the marketplace, and to this end, he considered Masscult benign, too forthright in its motives to be mistaken for anything but commerce. He found a larger threat in Midcult, which was similar to Masscult except that it “pretends to respect the standards of High Culture while in fact it waters them down and vulgarizes them.” Midcult was Masscult masquerading as art.

Television began as a strictly Masscult medium, and for most of its history remained indisputably so. In the Forties, the soap opera came to TV from radio as an instrument for selling cleaning products to housewives. The shows were produced by retail brands such as Procter and Gamble, and product promotions were woven directly into their story lines. During the postwar boom, cheap mass production made the television set a fixture of the American home, leading to the medium’s first Golden Age. Programs like Kraft Television Theatre, Chevrolet Tele-Theatre, and The Philco Television Playhouse established a new programming format, the anthology drama. Like plays, these were self-contained stories performed live on stage sets. Unlike plays, they were broadcast into the homes of millions of potential consumers of Kraft cheese, Chevy sedans, and Philco radios.

Beginning in the Fifties, the single-sponsor series gave way to commercial advertising as we know it: programs interrupted every few minutes with brief spots from multiple sponsors. The length and frequency of the interruptions increased over time, but this model, with some exceptions, remained largely unchanged through the next several decades. The goal of any given program was to attract advertisers by reaching the largest possible number of viewers. Networks performed extensive market research to test the viability of programs in development, and advertisers used Nielsen ratings—an audience measurement system—to determine both where to advertise and how much to spend on those ads.

The rise of cable in the Eighties divided market share among dozens of channels, prompting what some consider TV’s second Golden Age. Demographic targeting began to replace broad populism as a governing ethos. A series no longer had to reach twenty million viewers so long as it reached those most likely to buy a Ford truck or swear fealty to Pepsi. This was especially true for programs on cable, whose monthly costs narrowed its reach to a smaller group of consumers with more expendable income. But the networks, too, became amenable to unconventional programming. Miami Vice and Twin Peaks would have been too youthful and bizarro, respectively, to have reached prime time in a previous era, though both shows attracted large audiences. A better example of demographic targeting is thirtysomething, a talky series about Philadelphia yuppies. Despite limited appeal and low Nielsen numbers, thirtysomething ran for four years on ABC because the show did well in a coveted demographic: women between the ages of eighteen and forty-nine.

It was a short leap from cable packages to subscription-based channels that worked under a similar logic but targeted an even slimmer set of viewers, those willing to pay extra for “premium” content. In 1972, HBO began offering commercial-free programming to just over three hundred subscribers in the Wilkes-Barre area of Pennsylvania. The network radically expanded its reach when it became the first cable channel to broadcast via satellite, beaming in the Ali–Frazier fight from Manila in 1975.

Though its focus was on films and live events, HBO experimented with original content from the beginning, including standup comedy and children’s programming. In the late Eighties, home VCRs and big chain video stores rendered HBO’s central offering—recent films, uncensored—significantly less scarce, and a high churn rate (the ratio of canceled-to-new subscriptions) forced network executives to reconsider their business model. The network had had success with standup, so scripted comedy was a logical next step. A few early series drew critical acclaim, including The Larry Sanders Show, a showbiz mockumentary whose handheld camerawork, cranky protagonist, and profane dialogue gave a glimpse of what TV looked like when freed from the custodial demands of advertisers. In 1996 HBO changed its slogan from the Hallmark-ish “Something Special’s On” to what amounted to a mission statement: “It’s Not TV. It’s HBO.”

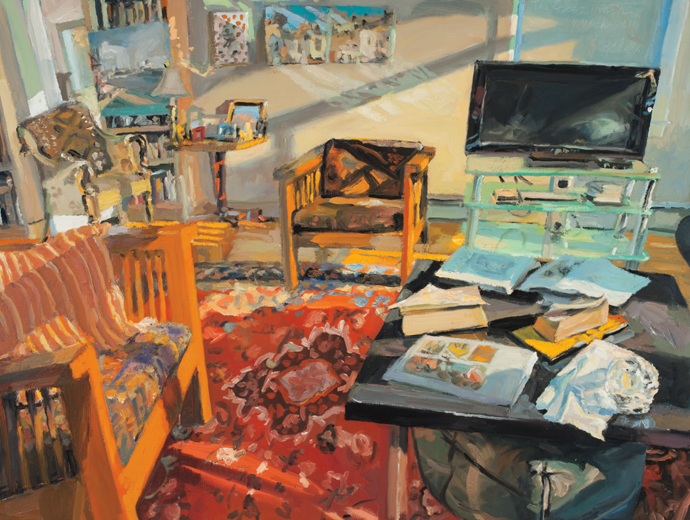

The Longest Winter, March 2011, by George Nick © The artist. Courtesy Gallery NAGA, Boston

That the HBO dramas of the late Nineties were some of the first ad-free American series outside of PBS can’t be overstated in discussions of their bearing on shifting cultural attitudes toward TV. While I’m too young to have watched Twin Peaks when it originally aired, I’d imagine that, despite the show’s art-house bona fides, commercial interruptions persistently reminded viewers that David Lynch’s weirdness was serving the network’s profit motive.*

Meanwhile, the early Aughts saw the spread of a slew of technologies, including home DVD players, the DVR, and On-Demand, that allowed viewers to watch and rewatch shows with convenience. The increasing popularity of high-definition plasma televisions supported more artful styles of TV cinematography and encouraged staying home. Burgeoning message-board culture provided forums for analysis that rewarded repeat viewing and led to passionate tribalism among fans. Networks cashed in by branding everything from Buffy the Vampire Slayer board games to Simpsons novelty beer cans, to Sopranos T-shirts and cookbooks and New Jersey bus tours. DVD box sets could be displayed on bookshelves as testaments to taste, and they provided networks with additional channels for revenue and dissemination. HBO strategically released a show’s previous season on DVD a month before the new season aired. Whereas the medium’s defining characteristic was once ephemerality, it was now seriality. The old logic dictated that each episode of a series be self-contained. In this new climate, series could tell extended stories over entire seasons; viewers were encouraged to catch up.

With its haughty air of exclusivity, “It’s Not TV. It’s HBO” was the product of keen demographic insight. The late Nineties pay-cable audience skewed suburban, consisting of affluent boomers and grown-up Gen X-ers. This was a cohort that saw itself as cultured, though decreased attention spans, the time suck of the internet, and the fifty-hour workweek left less room in their lives for the temporal and intellectual demands of novels, plays, and challenging films. This audience still identified as vaguely anticorporate, and it favored brands that, however paradoxically, affirmed that worldview. What this audience wanted was license to watch television while holding themselves superior to the kinds of people who watched television. It wanted what television already offered—weekly stories about cops, lawyers, criminals, and doctors—propped up by the illusion that spending Sunday nights in front of their flatscreens was commendably edifying. HBO sold them a treasured commodity: cultural capital.

The success of The Sopranos proved demand for “Not TV,” and the market responded—cable first, then the broadcast networks. A formula was established. Take a genre such as the police procedural, the space opera, or the vampire romance. Raise production values by halving the number of episodes per season as a budgeting strategy. Cast film industry discards: aged-out leading ladies, male character actors in slightly grizzled disrepair. If developing for pay-cable, add one to three instances of nudity per episode. Finally, reverse the genre’s central dynamic between protagonist and villain, so that the archetypal bad guy—serial killer, polygamist, treasonous P.O.W. turned Al Qaeda operative—is now our brooding and complicated antihero. Ideally this antihero will be a middle-aged, heterosexual white man with a wife and kids, hiding in plain sight in American suburbia. Three of the five will do.

Again, a confluence of market forces precipitated this altered paradigm. In the film industry, the mid-budget picture all but disappeared, leaving moviegoers to choose between blockbusters and indies. This had the dual effect of sending writers, directors, and actors in search of TV jobs, and opening a niche for the kind of grown-up content that Not TV was peddling. Meanwhile, reality TV had become the low man on the cultural totem pole, bumping scripted series up a notch and forcing them to chase a more sophisticated viewership.

A handful of series that emerged from this environment offered enlivening tweaks on the formula. Breaking Bad could be visually stunning, drawing its sepia palette and wide-angle camerawork from John Ford westerns. Mad Men walked a thin line between demystifying and fetishizing the Sixties, but its take on human nature was refreshingly cynical. The Leftovers trippily courted transcendence. And, while it hasn’t been eulogized with the same fanfare as the other formative HBO dramas, to my eye, Six Feet Under’s vision of a diverse and porous postnuclear family is unrivaled in both prescience and earned sentiment.

I’m sure there are a few that I’m forgetting, or never got around to watching, or that weren’t to my taste. I couldn’t get through Deadwood, but I couldn’t get through Blood Meridian either. I’m willing to accept that these failures are mine. Regardless, for every show that circumvented the prestige formula, a dozen more used its codified syntax to signal highbrow credibility. This is what happens to art under capitalism; success is cloned until the market shifts and something new worms its way into the zeitgeist. For years, publishers clamored for novels resembling The Corrections, until readers grew weary of Franzenian social realism and autofiction emerged as the new hipster chic. On TV, the high financial stakes encourage playing it safe. Penguin can afford to lose $20,000 on a risky debut novel; Warner Brothers spent $8.4 million producing The Leftovers pilot alone.

For a series to be green-lit, even on pay-cable, it must have a model for financial success. Hence the wave of cookie-cutter prestige dramas. Masters of Sex was Mad Men for pay-cable: same stylized nostalgia, now with nudity! Big Love was the The Sopranos in Utah, polygamists in place of the Mob. Boardwalk Empire—brainchild of Sopranos executive producer Terence Winter—put The Sopranos in a time machine back to Prohibition. Sons of Anarchy put it on Harley-Davidsons. Ray Donovan gave it a Boston accent. Westworld took Deadwood and added robots. Ozark is a cancer-free Breaking Bad. Writing in Esquire, Eric Thurm described this phenomenon as “serving you a Big Mac and convincing you it’s steak.” I’d suggest it’s more like slapping a brioche bun on a Big Mac and calling it farm-to-table.

More suspect than these series were the critics quick to parrot the networks’ marketing-speak. The Wire is a good show, maybe even a great one. It is not a novel, though critics refer to it as such, tacking on modifiers like “Dickensian” and “Great American.” Brett Martin calls it “one of the greatest literary accomplishments of the early twenty-first century.” Adam Kirsch argues otherwise in a 2014 New York Times op-ed on this subject, explaining that “it is voice, tone, the sense of the author’s mind at work, that are the essence of literature.” I’d add that novels—these days—aren’t generally serialized, and if they were, no “great” one could have as shoddy a fifth volume as The Wire did.

The false equivalence was self-serving, a justification for TV criticism as valid profession. It was vindicating for viewers, too, the arduous task of reading novels being no longer requisite for entry into the elite society of People Who Read Novels. It didn’t matter that the novelists writing for The Wire were Dennis Lehane and George Pelecanos, whose mass-market thrillers could be bought in airports. Their involvement in the series gave it literary cred.

Comparing prestige dramas to novels also helped rationalize their limited appeal. More than three million people watched the Mad Men finale, which sounds like a lot until we’re reminded that eighty million watched the “Who Shot J.R.?” episode of Dallas. When New Yorker critic Michael J. Arlen proclaimed in 1980 that “Dallas is ours,” he was referring not to his magazine’s modest and demographically narrow readership but to the culture at large. For those of us in our own modest demographic bubbles—bubbles that, increasingly, extend to what our algorithms show us online—Mad Men may have seemed like a Dallas-level national obsession, rather than what it was: a critical darling that averaged, during its most watched season, seventeen million fewer viewers per episode than The Big Bang Theory.

I point this out because the misperception of the prestige drama’s mass appeal tends to grant it critical allowances that novels and films don’t get. Golden Age evangelists love to wax rhapsodic on the artistic triumphs of their preferred series, but those same critics are quick to pull the “mass appeal” card to defend those series’ failings, reminding naysayers that, unlike the snooty purveyors of fine art and literary fiction, showrunners, both valiantly and by necessity, take a populist approach. These critics remind us that a series lives or dies at the mercy of its lowest common denominator of viewer, so fans must accept some level of compromise if we want our favorite shows to survive. But that viewer turns out to be not the MAGA-hat philistine of our nightmares, who isn’t watching Mad Men in the first place, but the risk-averse executive.

Despite the eagerness of writers like Sepinwall and Martin to paint showrunners as sovereign auteurs, their books document an astounding amount of network interference in the creative process. Take Friday Night Lights. Helmed by Jason Katims, the series, which followed a high school football team, had a distinct visual style and featured a cadre of talented actors. It spent its first season commendably avoiding cliché. Referring to F.N.L.’s nuanced handling of race and abortion, Katims explained, in an interview with Sepinwall, “There was a trust built into the relationship where they [NBC] felt we could handle these things in a way that was going to respect all the characters involved.” And yet, that first season concludeson the most hackneyed of sports tropes, the last-second, come-from-behind championship victory.

According to Sepinwall, Katims scripted this ending in the hope that its concession to feel-goodism would secure NBC’s interest in a second season. The ploy worked; the series was renewed. But the imagined appeal of cheaply formulaic storytelling betrayed an underestimation of F.N.L.’s audience. This would become clear when the show’s fans turned against its second season, which was framed around a hacky murder plot.

Or take Mad Men. Matthew Weiner, the only showrunner ever to have been granted a Paris Review interview, is known as a dictatorial artiste. Sepinwall’s account of the series makes continual mention of AMC’s hands-off treatment of Weiner’s process. Yet an executive’s note on Weiner’s pilot script—that the show’s central character, Don Draper, needed “a secret”—led to the series’s largest misstep, the heavy-handed origin story that has Draper raised on a farm under the name Dick Whitman, a name he later discards after stealing the identity of a comrade who was killed in the Korean War. This thread, which runs throughout the series and informs some of its major narrative events, is too metaphorically obvious—we get it, Don’s a self-made man.

Even the notoriously uncompromising David Chase caved under network pressure on at least one occasion. “College,” the fifth episode of The Sopranos’ first season, is often touted as a defining moment for the TV antihero. In the episode, while taking his daughter on a tour of liberal arts colleges in Maine, Tony comes across a former associate living a quiet civilian life in witness protection years after ratting out some of Tony’s pals. Tony, unhindered by any sense of moral anguish, garrotes the man in broad daylight with a length of cable. Albrecht, who was HBO’s head of original content at the time, worried that Tony’s gleeful killing of such a seemingly innocent victim would turn the audience against him. He allowed the scene to remain in the episode only after Chase agreed to add earlier scenes in which the victim is seen dealing drugs and plotting to kill Tony himself. “I don’t think it was a terrible compromise, but it was a compromise,” Chase told Martin. “I wish we hadn’t done it.”

We know what Macdonald would say: these appeasements to the market categorically debase the product. Perhaps this is true. With few exceptions, a primary goal of any series is to stay on the air. A series is a business, employing hundreds of workers, sometimes thousands. Its cancellation means the forfeiture of these jobs. Even on premium cable and streaming services, the goal of recurring renewal is at odds with the auteurist fantasy of artistic autonomy. As the film critic David Thomson explains in Television: A Biography, “the setup of the show becomes its own persistence (and profitability), and any imperative of necessary drama is compromised by the desired continuity.”

Under these circumstances, it’s understandably rare for a series to feel aesthetically cohesive from start to finish, but this is the trade-off for what makes TV such a popular and potentially relevant medium: its living perpetuity. A TV series can continue to evolve over time in a way that novels and films—finite documents—can’t.

A recent solution to Thomson’s problem of desired continuity is the reemergence of the anthology. A show like True Detective or American Horror Story tells a complete story across a single season and then resets, returning with different characters and story arcs only thematically connected to the previous volume’s. It’s an appealing concept, and some interesting series have made use of the format. But these series are limited in terms of what they offer viewers.

One reason that TV shows develop cult followings is that to watch one from beginning to end—NBC’s The Office, say, which ran for nine seasons and over two hundred episodes across eight years—is to spend a significant portion of your life among its characters. You could read To the Lighthouse or watch The Big Lebowski half a dozen times and not come close to approaching those numbers. While I’ll go to my grave defending the superiority of the original thirteen-episode BBC version of the show over its American counterpart, NBC’s Office still feels definitive; I reference Pam and Jim in conversation, never Dawn and Tim.

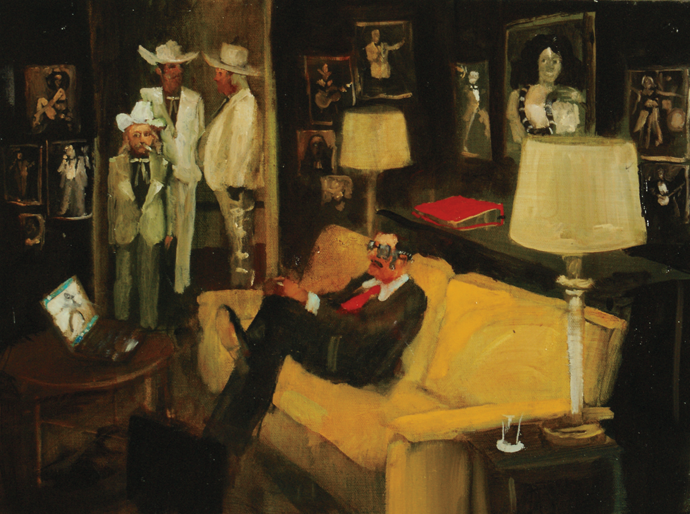

Talent Man, by Michael Harrington © The artist. Courtesy Galerie de Bellefeuille, Montreal and Toronto, and Galerie St-Laurent + Hill, Ottawa, Ontario

When we first meet Tony Soprano, in 1999, he is robust and handsome, if not exactly svelte. By the Season 4 finale, some five human years and forty-three TV hours later, Tony looks significantly worse for wear. His marriage is ending, and we watch its death knell. The time we’ve spent with this couple increases our investment. And by the end of the series—by this point we’re eight years and more than seventy hours in—we’ve witnessed Tony and Carmela reconcile, resigned to their chosen lot. Tony—and, by extension, James Gandolfini—is obese now, breathing heavily. (Gandolfini would die of a heart attack six years later, imbuing his performance with the retrospective feel of cinéma vérité.) The series ends with the screen going black on this family unit, waiting for death. It’s been said that the theme of The Sopranos is that people don’t change. What makes it a powerful show is that we feel them not change across those cumulative hours. The felt passage of time runs hauntingly perpendicular to this emotional stasis.

Whether this means The Sopranos is art or that I’ve been manipulated by a high-quality middlebrow product, I can’t say. Art is notoriously difficult to define, and, like pornography, a know-it-when-you-see-it proposition. In the parlor game I played with my old roommate, The Sopranos sat beside Truffaut in Good-Good. Fifteen years on, that kind of cataloguing feels reductive and irrelevant; it was the province of idle youth, and these days it’s the province of Twitter and listicle purveyors such as BuzzFeed, Vulture, and, increasingly, the New York Times. The more interesting question is not whether TV can be art but why we, as a culture, remain so invested in its validation.

To answer that question, it’s worth tracing the path of a genre that runs parallel to the prestige drama: the single-camera comedy. If I’ve largely avoided comedy thus far, it’s because the critics I’ve been discussing tend to downplay its role in the recent Golden Age. They’re not alone in their disregard. Historically, comedy has been thrown on the cultural trash heap, piled into the DVD bargain bin. This is true across mediums. As the late Village Voice critic Andrew Sarris was fond of pointing out, movie comedies almost never win Oscars. While satirical novels such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Catch-22, Slaughterhouse-Five, and Portnoy’s Complaint were celebrated in the Sixties, “satire” is a dirty word in publishing these days, excised from jacket copy for fear of alienating a readership devoted to the humorlessly earnest. These readers, I’d venture, get their laughs from TV.

Situation comedies like I Love Lucy and The Jack Benny Program were integral to TV’s first Golden Age, The Cosby Show and Cheers to its second, and the genre has remained popular, as The Big Bang Theory’s ratings attested. Sitcoms have also, historically, been subject to derision for their paint-by-numbers plotting, hokey stage sets, and canned laughter. But the same conditions that precipitated the prestige drama encouraged a new style of TV comedy that upended the sitcom’s rigid conventions.

Seinfeld, which ran on NBC from 1989 to 1998, is a transitional series. Early episodes look sitcom-ish. A laugh track punctuates the punch lines, and action is largely confined to a handful of stage sets. As the series progressed, short synthesizer riffs (which are often mistaken for electric bass) supplemented the laugh track, and more and more scenes were shot on location, which meant abandoning the sitcom’s traditional three-camera setup in favor of the roaming, single-camera style that would soon become prevalent. Its characters weren’t the violent kind of antiheroes that would populate the prestige dramas, though they were callous and incapable of personal growth.

But even at its weirdest, Seinfeld resembled a sitcom, albeit an atypically unsentimental one. The single-cam comedies that began to trickle out in the late Nineties and early Aughts were farther removed. Like the prestige dramas, they embraced seriality, which allowed for more extensive character development. They courted ambiguity by forgoing canned laughter, demanding at least a modicum of viewer engagement.

These genre-straddling series didn’t fall neatly into the cultural hierarchy, but one can’t deny that Sex and the City and Curb Your Enthusiasm were as vital to the Not TV brand as their hour-long counterparts, and did as much to shape the zeitgeist. Fifteen years after the show’s finale, a three-and-a-half hour Sex and the City bus tour of Manhattan still runs daily; the Sopranos tour runs twice a week.

So why aren’t these or other innovative comedies, like Weeds, 30 Rock, and Arrested Development, discussed with the same reverence as the foundational prestige dramas? These series drew critical acclaim, but I’ve never heard Tina Fey likened to Shakespeare, though the Bard wrote his share of comedies, too.

In part, this is because comedy, almost by definition, doesn’t signal gravitas in the way that drama does. On TV, comedies are shorter, and the pacing is less ponderous. Violence tends toward the cartoonish. Compare the maudlin strings of Mad Men’s theme music with the bouncing tubas of Curb’s. In a piece that originally appeared in The New Yorker, Emily Nussbaum proposes that these comedies—particularly Sex and the City—are overlooked by virtue of

an unexamined hierarchy: the assumption that anything stylized (or formulaic, or pleasurable, or funny, or feminine, or explicit about sex rather than about violence, or made collaboratively) must be inferior.

If this argument sounds familiar, it’s because, in the early Aughts, the poptimist music critics made a similar case for previously maligned styles such as disco, hip-hop, and pop country. The “rockist” canon-makers, these critics contended, were elitist, white, heterosexual men, and they used aesthetics as a smoke screen for cultural bias. Disco, for example, is a fundamentally queer and African-American form, and rockists lack the context necessary for critical engagement.

In Difficult Men, Martin acknowledges that the prestige dramas he celebrates are largely the creations of straight, middle-aged white guys. He ventures that this reflects Hollywood’s power structure but also that “the autocratic power of the showrunner-auteur scratches a particularly masculine itch.” There were exceptions. Alan Ball, the creative force behind Six Feet Under and True Blood, brought a queer sensibility to both series, neither of which receives much more than cursory treatment from Martin and Sepinwall.

Nussbaum’s I Like to Watch: Arguing My Way Through the TV Revolution, which collects slightly more than a decade’s worth of columns for New York and The New Yorker, is meant as a corrective. Hers is an inclusive brand of criticism, the “yes, and” approach, to borrow a term from improv comedy. She doesn’t want to demolish the monument to the prestige drama, but to erect, by its side, a monument to those series—single-cam comedies, but also network sitcoms and procedurals—that the critical hegemony has ignored. Nussbaum traces the modern female antihero to Sex and the City’s Carrie Bradshaw. Carrie didn’t garrote snitches with electrical wire, but she did smoke cigarettes, sometimes even indoors. Sex and the City was “high-feminine instead of fetishistically masculine, glittery rather than gritty.”

It’s been suggested that the truest innovation of the early prestige dramas was adorning the soap opera—historically considered a feminine form, both for its domestic origins and its focus on relationship dynamics—with masculine signifiers, creating a product whose appeal cut across gender lines. Oz’s prison setting and extreme violence—its “grit”—made the queer love story at its center palatable to the hetero male portion of its audience. When Sopranos fans complained that Season 4, which focused on Tony and Carmela’s relationship, had “too much talking, not enough whacking,” this was a coded way of saying that the show’s balance had tipped too far toward the yin.

Sex and the City, then, was a pioneering series, not for its depictions of sex but for its discussions of it: all those Sunday brunches at which Carrie and company deconstruct their encounters, emphasizing male failure. Its sexual politics may feel outmoded in 2019, but the series cleared a path for millennial progeny such as Girls, Broad City, and Fleabag, which have further pushed the boundaries of female impropriety.

I’d also argue that, despite their differences, both The Sopranos and S.A.T.C. poignantly tracked the passage of time. Whereas The Sopranos gathered pathos by juxtaposing that passage with emotional stasis, S.A.T.C. did so by juxtaposing it with the more concrete stasis of Carrie’s romantic predicament—single and dating—as she advanced in age from early to late thirties. The Sopranos continually punished its characters—and its viewers—for fetishizing the spoils of criminality, bludgeoning us with their moral and psychological costs. I’d always thought of S.A.T.C., by contrast, as an unapologetic celebration of consumerism, but over the course of its run, which I rewatched as research for this essay, Carrie’s consumerist vision of romance is continuously revealed to be the source of her suffering, and shopping—her coping mechanism—an insufficient balm.

In parallel, S.A.T.C. captures another transition, that of Manhattan after 9/11. So much analysis of Mad Men revolved around the way it tracked the Fifties into the Sixties and then the Seventies. This is pro forma praise for a period piece. It’s a more difficult quality to identify in something set in the ongoing present. The September 11 attacks occurred during the run of Season 4 of S.A.T.C. Though the tragedy is addressed only obliquely, the show undergoes a tonal shift that reflects the maturation of both Carrie and the city.

To Nussbaum’s point, S.A.T.C. did as much to shape the Golden Age as any other series, and it’s absurd that histories of the era ignore it. Still, I take issue with the way that Nussbaum sneakily lumps “formulaic” in with “pleasurable” and “funny” on her list of unfairly denigrated qualities. Plenty of great art has eked out originality from within the strictures of genre. For example, the twelve-bar blues is a simple and unyielding song form, but its execution can be wildly varied. The problem, when it comes to TV, is that a broad-spectrum lenience toward formula makes it too easy to forgive artistic laziness. S.A.T.C., for one, could have done without the pun-happy pop psychology of Carrie’s columns; I shuddered every time poor Sarah Jessica Parker was made to pensively stare into her laptop while her own voice muttered inanities offscreen. Well-regarded indie filmmakers Allison Anders and Nicole Holofcener directed episodes of S.A.T.C. Critics would not forgive these hackneyed shortcuts in their films.

Although she wouldn’t praise a TV show by calling it a novel, like Seitz, Sepinwall, and Martin, Nussbaum wants it both ways, to celebrate series for toppling genre conventions and to absolve them when they don’t—for the TV she loves to be given critical consideration as serious art, and to be let off the hook when it behaves like TV. A TV poptimist, she argues that our critical rubrics should be genre-specific, but the rubrics she proposes too easily bend to her rhetorical needs.

When discussing the transition from the Golden Age to Peak TV, critics tend to focus on the shift in viewing habits brought on by the ascent of streaming as the primary method of television consumption. Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon Prime cultivated binge-watching by releasing whole seasons of a series at once, rather than in weekly installments. Binge watchers cycle through series more quickly, which creates increasing demand for content. The volume of new series being produced means that talent and resources are spread thin, and also that networks and streaming platforms have less to lose from commercial flops. Quantity is valued over quality. Audiences continue to consume ravenously. In Let’s Talk About Love, his book-length essay on Céline Dion and the formation of taste, the music critic Carl Wilson suggests that “ranking lastingness above novelty is a holdover from an aesthetic of scarcity, predating the age of mechanical, or digital, reproduction.” Ephemerality begets seriality begets disposability.

Poptimism emerged under a similar shift in consumption habits brought on by technological advancement—the digitizing of music and music discourse—and I’d argue that the triumph of TV poptimism is as essential to the Peak TV narrative as the rise of streaming. The way we watch TV has changed, and so has the way we talk about it. Advertisers have navigated this shift in viewing habits, finding new ways to push their products, and viewers have similarly adjusted, constructing fresh rationales for our obsessive consumption. Cultural capital has been redistributed, Bernie Sanders–style. Comparing The Wire to Dickens now feels quaint. These days, book publicists promote novels by likening them to TV shows.

Nussbaum chronicles this transition, and her career arc is emblematic of it. As a graduate student studying the Victorian novel in the late Nineties, she had a life-altering epiphany while watching an episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer in which hyena-possessed high schoolers eat their principal. She later dropped out of her Ph.D. program to work as a writer and editor for Lingua Franca, Slate, and the New York Times. She landed at New York, where one of her lasting contributions was The Approval Matrix, a back-page feature that amounts to a slightly more sophisticated version of the Good-Bad system. In 2011, Nussbaum replaced Nancy Franklin as The New Yorker’s TV critic, and there she would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize, in 2016. When Nussbaum declares that her side has won the “drunken culture brawl,” she is referring, in part, to her own institutional sanction.

Nussbaum isn’t always positive. Her takedowns can be scathing, often enjoyably so. But in her eagerness to democratize the canon, she’s overly generous to that which she thinks has been unfairly ignored. This attitude may stem from years spent arguing on message boards filled with sycophants, haters, and few in between. It may also be a function of surplus and the utility of hyperbolic praise in making your subject stand out from the field. Either way, this unapologetically partisan approach is what makes Nussbaum such a popular critic: she’s first and foremost a fan. When she does criticize a series she loves—Lost, for example—she criticizes with a fan’s sense of personal betrayal.

Nussbaum reckons with a different kind of betrayal in “Confessions of the Human Shield,” a long essay written exclusively for I Like to Watch. Reflecting on #MeToo, she asks what’s to be done with things we love that turn out to have been made by despicable men. There aren’t easy answers. It is a nuanced, searching essay, and nobly inconclusive. Nussbaum cops to the relative ease of “canceling” work that never appealed to us, the difficulty of doing the same for that which has affected our lives. She forthrightly examines her own complicity; Nussbaum interviewed Louis C.K. at The New Yorker Festival in 2016 even after being tipped off to the allegations against him, which were not yet public. She did not back out of the event or ask the hard-hitting questions that she felt deserved answers. She neither defends nor denies her behavior.

I feel for Nussbaum. She risked championing C.K.’s transgressive work, and it landed her in an unenviable situation. I admire the candor with which she writes about these events. I also understand why, in their aftermath, a strain of moral anxiety begins to dominate her thinking. This strain has always been there—as early as 2013, she expressed concern that Breaking Bad attracted “bad fans” who cheered for violence meant to unsettle—but it has intensified in the years following Trump’s election and the troubling revelations of #MeToo. This anxiety feels of a piece with a larger trend in arts criticism: the displacement of aesthetics by ethics as the primary lens through which we view culture. And in this climate, there is nothing more suspect than irony.

Back in the mid-Aughts, among the Good-Bad series I watched “ironically” was NBC’s The Apprentice. A commercial success, The Apprentice ran for ten seasons and, it’s been suggested, revitalized Donald Trump’s career. On some subconscious level, then, Trump’s presidency feels like punishment for our ironic detachment and the slackening of moral vigilance it allowed for. Ditto #MeToo: the allegations against Bill Cosby, Louis C.K., and Kevin Spacey (to name just a few) leave viewers feeling as though their fandom has tacitly fostered these actors’ behavior. As a culture, we’re understandably anxious about endorsing that which we suspect might be morally debased. Writing in The New Republic, Rachel Syme argues that simply by referring to the era as a Golden Age, the culture has “[created] an environment where the artists working within the medium can be seen as indispensable, invincible, and ultimately unaccountable.”

The danger, though, is that we’ve begun to resist ambiguity in the work itself. On Twitter, where she has more than a quarter million followers, Nussbaum wrote that the most recent season of Curb Your Enthusiasm “feels like a show about a rich guy hassling service people & I’m not in the mood. I can’t tell what changed: the show, the world or me.” The lifestyle blog Revelist worried that shows like Orange Is the New Black and 13 Reasons Why “normalize abusive relationships.” At The Whisp, another lifestyle blog, a post accused The Sopranos of “blatant” homophobia. On a list of “The 17 Most Toxic Male Characters From TV Shows,” Bustle condemned The Office’s Jim Halpert for “making decisions without consulting his wife first” and for being “mean” during the prank war with his colleague, Dwight. A similar list on BuzzFeed called out The Office for its “irresponsible portrayal of the ‘perfect’ guy.” These writers seem to be suggesting that a failure to clearly label flawed characters as villains amounts to an endorsement of the full spectrum of their behaviors.

With other morally compromised characters, such as the assassin Villanelle on the BBC’s Killing Eve, critics read elevated intentions onto Tarantino-ish carnage: Slate critic Inkoo Kang refers to the show’s “unique feminist camp,” the Guardian’s Chitra Ramaswamy writes that the series takes the “tired old sexist tropes of spy thrillers then repots them as feminist in-jokes,” and Salon’s Melanie McFarland suggests that it explores “patriarchy’s impact on the already delicate complexities of female relationships.” The Golden Age narrative rationalized the educated class’s TV consumption by calling it art. These days we rationalize it by calling it woke.

These rationalizations let viewers off too easy. Not to renege and act all precious about Art, but I think that one of its jobs is to confront us with our own complicity, force us to reexamine our most deeply held beliefs. In interviews for The Sopranos Sessions, David Chase expresses frustration that fans sympathized with Tony, who was supposed to be a villain. I find this disingenuous. The whole series is geared around gathering that sympathy and throwing it back in the viewer’s face. That’s a large part of the power of The Sopranos; we’re forced to reckon with our voyeuristic bloodlust. I imagine that Tony’s therapist, Dr. Melfi, would suggest that Nussbaum’s discomfort with “bad fans” betrays an anxiety, however unconscious, that she might be one herself.

Congruently, we’ve become quick to venerate that which offers—or appears to offer—access to the moral high ground. Wokeness has become a form of cultural capital. In most ways, this is good. Nussbaum’s book includes profiles of the showrunners Kenya Barris, Jenji Kohan, and Ryan Murphy. Barris is African-American, Kohan is a woman, and Murphy is queer. All three have helmed critically lauded and commercially successful shows, and have done so using casts and crews heavily populated by people with diverse racial, sexual, and gender identities. Compared to what the industry looked like ten years ago, this is real progress.

But Nussbaum’s profiles paint this progress as the product of fiscal opportunism rather than altruism. Here she is on ABC’s green-lighting of Barris’s Black-ish:

Racial critiques of Girls—and the simultaneous rise of Black Twitter—had scared executives into at least paying lip service to diversity . . . A Nielsen report found that black viewers watched 37 percent more TV than other demographics. It seemed like the right moment for an idea-driven sitcom about race . . .

This is how the sausage gets made, packaged, and sold. It’s a good reminder that when TV critics use the word “revolution,” they don’t mean the violent overthrow of corporate overlords. Their revolution is the capitalist kind: progress by way of shifting demographics, reinforcement of the corporate status quo.

This becomes strikingly clear when the economics don’t line up. In March, Netflix canceled the sitcom One Day at a Time despite it being celebrated as a doyen of wokeness.

When fans revolted on Twitter, the streaming service offered a series of apologetic tweets:

The choice did not come easily—we spent several weeks trying to find a way to make another season work but in the end simply not enough people watched to justify another season . . . to anyone who felt seen or represented—possibly for the first time—by ODAAT, please don’t take this as an indication your story is not important. The outpouring of love for this show is a firm reminder to us that we must continue finding ways to tell these stories.

Netflix doesn’t share data regarding how many people are streaming its shows, so we’ll never know, specifically, what “not enough” means. What is clear is that corporations continue to behave like corporations. All that’s changed is that they’ve been pressured into pretending they don’t.

Barris envisioned Black-ish appearing on a cable channel, where he’d have more creative freedom, but he couldn’t turn down ABC’s offer, and it’s hard to blame him. Not only would Barris get more money at ABC, but his half-hour series about an African-American family navigating white suburbia would have a substantially broader reach. Black-ish embraces issues of race, exploring subjects like police shootings with a sophistication rare for its genre. The show’s presence on network prime time is both proof of political progress and a method of furthering it. But the ABC deal was not without compromise. Barris had to change his protagonist’s job from TV writer to advertising executive in order for the series to more easily feature sponsored products. Barris admits to Nussbaum that one Buick-centric episode is, essentially, “a commercial, dude.”

Again, I don’t begrudge Barris this devil’s bargain; selling Buicks isn’t the worst thing in the world. But I did think of it when I read in Variety that ABC had killed a “politically and socially themed episode” of Black-ish as a result of creative differences with Barris. It later came out that the episode featured, among other things, news footage of Donald Trump, the Charlottesville attacks, and N.F.L. players protesting during the national anthem. Barris has been reluctant to discuss the situation, and it’s unclear how much influence the show’s sponsors had in ABC’s decision. At the online magazine The Root, Michael Harriot decoded ABC’s language:

We know that “mutually agreed,” in black parlance, means, “These white folks made the decision.” We mutually agreed to pick cotton for 400 years. We “mutually agreed” to Jim Crow. We “mutually agreed” to systemic inequality. We are tired of mutual agreements.

Super Blue Omo, acrylic, transfers, colored pencil, and collage on paper, by Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Artwork photographed by Peter Hauck. © Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, London, and David Zwirner, New York City

If The Sopranos was the Golden Age’s representative text, then most will agree that Peak TV’s is Game of Thrones. There have been better shows, certainly. Comedies, which are cheap to make and quick to shoot, have benefited from the market circumstances of the current moment. Lowered stakes and diminished oversight have granted creators more freedom, and niche, eccentric shows such as Atlanta, High Maintenance, American Vandal, and PEN15 have flourished in this environment.

But Thrones, which ended in May, was that rare thing in the era of Peak TV: a mass cultural phenomenon. Forty-six million people watched the final season across all platforms. More than nineteen million actually saw the finale live, presumably worried about spoilers.

The series, it seemed, had something for everyone: dragons, castration, military strategy. It feinted toward the highbrow with pyrotechnic cinematography, high-end costumes, British accents, and the very good acting of Lena Headey, Peter Dinklage, and others, who frequently imbued lifeless dialogue with nuance and emotion. Critics compared Thrones to Shakespeare. Harvard offered a class on it. The presence of a female commander in chief leading an uprising of peasants and slaves led many viewers—Daniel Mendelsohn of The New York Review of Books and Senator Elizabeth Warren among them—to read the series as a parable of wokeness. The dragons, weaponry, and dense genealogies lent themselves to fantasy geekery. The nudity—gratuitous even by HBO’s standards—lent itself to a different brand of fantasy, the kind commonly practiced by teenage boys.

For millennials who grew up on Harry Potter, Thrones may have felt like a natural progression; Westeros is where you go when you graduate from Hogwarts. Jon Snow, the show’s closest thing to a protagonist, strikes me as Tony Soprano’s opposite, an earnest moralist, existentially unbothered. And whereas The Sopranos felt singularly American, a classic immigrant story about disillusion and the American dream, Thrones was a model of globalization, a wideband broadcaster of consumerist good cheer.

That is, until the show’s final season somehow managed to enrage all sectors of its fan base. Complaints ranged from the technical (faulty lighting made a battle sequence hard to see; a Starbucks cup was accidentally caught in frame), to the political (the parable of wokeness became a misogynistic portrayal of female hysteria), to the personal (Jon Snow didn’t pet his dire wolf goodbye!).

Mostly, complaints centered on the diminished quality of the show’s writing. In fairness, the writing was truly awful. But these fans seem to have willfully misremembered the writing on earlier seasons, which was only marginally better. Regardless, more than 1.7 million people signed a Change.org petition requesting that HBO rewrite and reshoot the entire final season. Whether this displays a fundamental understanding of capitalism or a fundamental misunderstanding of it, I’m not sure. On the one hand, the signees recognize themselves as consumers. On the other, power lies in the consumer’s ability to withhold capital. For these fans, sadly, it’s too late.

Recently, my wife and I spent a week in and around Dubrovnik, the Croatian port city on the lip of the Adriatic Sea where much of Thrones was filmed, including the penultimate episode’s extensive battle sequence, during which the fictional city of King’s Landing is burned to smoldering ash by a fire-breathing dragon. The real Dubrovnik took heavy shelling of a less fantastical sort back in 1991 while under siege by Serbian and Montenegran forces. In the decade following the war, UNESCO’s restoration efforts in the old city led to its emergence as a tourist destination, especially for cruise ships.

Over the past few years, the city has become a kind of Disneyland for Thrones fans. Shop windows feature Daenerys Targaryen mannequins in fur and leather regalia, all available for purchase. Inside the shops, one finds branded beer steins, flags bearing Stark and Lannister family crests, lots of swords. The stone streets are filled with tour guides walking backward and pointing out the sites: the entrance to the Red Keep, Littlefinger’s brothel. Trailing tourists in varying states of cosplay snap photos and film themselves reenacting scenes. The Jon Snow cape is a popular look, though the sweat-drenched gentleman I saw wearing a sorry ladies, i’m in the night’s watch T-shirt better captures the overall vibe. On the steps of the city’s medieval cathedrals, violin buskers play the “The Rains of Castamere,” the theme of the Lannister House. Their baskets overflow with dollars, euros, and yen. When my wife and I visited Dubrovnik’s war photography museum, we saw photos of the city under siege, including one in which dozens of pigeons flee artillery shells falling on the Jesuit Stairs in the old city’s center. To reemerge onto the streets where costumed adults fought with plastic swords was to witness a bizarre erasure; fiction had displaced history in the cultural consciousness. Now tourists posed on the Jesuit Stairs, the site of Cersei Lannister’s “Walk of Shame” from the fifth season of Thrones.

And yet, Thrones has boosted Dubrovnik’s economy and offered the city a sought-after new identity. This, after all, remains television’s two-pronged promise: an escape from reality and a place for vendors to hock their wares. Before leaving I bought a spiked mace key chain to give to a friend back home.