Discussed in this essay:

Henrik Ibsen: The Man and the Mask, by Ivo de Figueiredo. Translated from the Norwegian by Robert Ferguson. Yale University Press. 704 pages. $40.

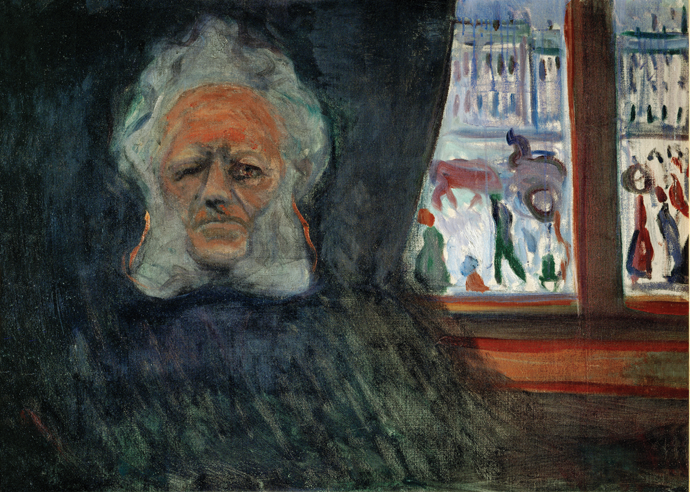

Henrik Ibsen, by Edvard Munch © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City/Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York City

In early 1879, scandal struck the Scandinavian Society in Rome. At a board meeting for the expatriate arts club, the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen criticized its rules forbidding women from serving as society librarian and from having votes on the board. Abandoning his prepared notes in eloquent indignation, Ibsen argued that women should not only have full voting rights, but also that, if they were allowed to apply for the librarian job, their applications should be favored over those of male candidates. He challenged his fellow members not to be “men with little ambitions and little fears,” claiming, “I fear women . . . as little as I fear the true artist.”

“Ibsen as agitator!” one member later wrote with surprise. Although the playwright was known to have strong opinions, and could become voluble when drunk, he was hardly a radical. Since the publication in 1866 of Brand, a verse drama about an uncompromising priest that won him fame in Scandinavia, he had sedulously cultivated relationships with royalty and proudly wore, whenever he was in public, the medals they had bestowed on him. Ibsen had never before seemed especially concerned about the status of women, in the Scandinavian Society or in society at large, and he was generally thought to lean conservative in his political views.

Only the motion concerning the librarian position passed, yet Ibsen did not give up the fight. At a banquet later that winter, he delivered a speech lambasting his opponents—the small-minded men who had voted against his proposals as well as the Scandinavian women in Rome “for whom his gift had been intended” and who he believed had plotted against him. “What sort of women are these,” he asked, “what sort of ladies, what manner of females, ignorant, in the most profound sense uneducated, immoral, on a level with the lowest, the most wretched . . . ” A duchess fainted from shock and had to be carried out of the room, but Ibsen continued speaking. An attendee recalled that when he finished, he walked to the exit, put on his coat, and left, “calm and silent.”

Unknown to the Scandinavians gathered that evening, Ibsen was then planning A Doll’s House (1879). The play concerns the slow dissolution of the marriage of the Norwegian couple Nora and Torvald Helmer, as Nora fears Torvald will learn that she forged a signature to secure a loan that helped save his life. It famously ends with the sound of the front door slamming shut as Nora departs in search of “an understanding of myself and of everything outside,” leaving Torvald onstage, deeply confused by his wife’s dissatisfaction. Nora’s abandoning her husband and children was an unprecedented resolution to a play, and, moreover, considered deeply immoral. German censors wouldn’t allow A Doll’s House to be performed unless the ending was changed so that Nora would stay with her family (Ibsen undertook the bowdlerization himself). In Britain it had to be produced by a private theater to evade the authority of the Examiner of Plays. When it was put on in London in 1889, one reviewer called the characters “the most unpleasant set of people it has ever been the lot of playgoers to encounter,” and Nora was deemed to be “absolutely inhuman.”

Europe at that time was gripped by political questions concerning the place of women in society, free love, the expansion of the franchise, and the importance of scientific inquiry in civic life. Before long, Ibsen, with his white muttonchops and pursed lips—and despite his diminutive height of five feet three inches—became one of the towering cultural figures of the age, his plays and their indictments of fin-de-siècle society fiercely debated in the European press. Each of his works, from A Doll’s House until the end of his career, brought him notoriety, with their depictions of families held together by lies, marriages destroyed by unreciprocated sexual desire, incestuous fantasies, and hypocritical government officials and titans of industry.

Progressives lionized him. George Bernard Shaw was a besotted admirer, seeing Ibsen as (in the words of the scholar Martin Puchner) “a Norwegian Shaw,” the enemy of every outdated institution. Shaw set part of his second play, The Philanderer, at the fictitious “Ibsen Club” in London, where gender parity was vigilantly practiced. (Shaw likely knew nothing about the Scandinavian Society incident.) To Shaw, Ibsen represented all things new and rational, the scourge of Victorian sentimentality and social conservatism.

But Ibsen’s plays persist (his work is performed more than that of any other playwright besides Shakespeare) not for his ability to place political problems onstage, but rather for their formal brilliance—the undeniable skill of his plotting and characterization—and, more important, his recognition that political opinions are often shaped more by one’s past, temperament, frailties, and ambitions than by reason. Like those of Turgenev and Dostoevsky, Ibsen’s characters show that we cannot live without ideals but are almost always too weak to live up to them. Ibsen’s drama has few outright heroes: every attempt to do good contains selfish motives and often causes harm to someone else. Though his plays are grounded in the concerns of the late nineteenth century, the moral ambiguity with which his characters struggle is comparable to that found in Sophocles, Shakespeare, and Kleist.

“I write to describe human beings,” he said. Although Ibsen never turned down an invitation to be feted by a student league or feminist group, he frequently claimed that his work was not political; if any of his plays reflected the ideas of reformers, it was “without any conscious intention on my part.” “What appeals to him,” the Norwegian historian Ivo de Figueiredo writes in his biography of Ibsen, newly translated into English, “are the spirit of revolt and the willingness to act, not necessarily the aims” of revolutions or movements. “The only thing about liberty that I love,” Ibsen told the Danish critic Georg Brandes, “is the fight for it.”

This stance could have pleased few besides himself. In 1898, at a banquet held by the Norwegian Women’s Union in his honor, Ibsen denied that he had meant to further female emancipation. “For me,” he said, “it has been a question of the liberation of humanity. And careful readers of my books will understand this. It is of course desirable to settle the women question, but as a corollary, not as a primary aim.” Figueiredo plausibly suggests that this was an exaggeration, intended to oppose “the reduction of literature to the status of a socio-political pamphlet.” Nonetheless, Max Beerbohm was surely right in saying that, after Ibsen’s speech, “quite feminine tears were shed, thereupon, by strong-minded women in every quarter of the globe.”

Henrik Ibsen was born in 1828 in Skien, a prosperous town about eighty miles southwest of the Norwegian capital. His father, Knud, after losing a distillery he owned, descended into cynicism and drink, and his mother, Marichen, hid from acquaintances out of shame. The family never recovered financially, and in 1843 Ibsen was sent away to work as an apothecary’s apprentice. He painted and stayed up nights to read and write, impressing his friends with his energy and the townspeople with his poetry. When he was eighteen, he had an illegitimate son with his employer’s maid. Father and son met only once, in the early 1890s, when the son asked his estranged and now famous dad for money and was promptly turned out.

The romantic nationalism that emerged in 1848, during the democratic revolutions against monarchs and emperors throughout Europe, appealed strongly to Ibsen, as it did to many of his generation, who were attracted to the notion that a people and its history formed the basis of a state. Ibsen and his peers sought not only to create art that drew on Norwegian culture, but also to establish institutions that could support their work. Norway, which had been under Swedish control since 1814, lagged culturally behind other European countries, including its Scandinavian neighbors. In 1850, when Ibsen’s first drama, Catiline (about the Roman nobleman who staged a failed coup in 63 b.c.), was published, no play with serious literary intentions had appeared in Norway for seven years.

In 1858, after working for seven years as an assistant director at a theater in Bergen—where he also wrote plays based on Norwegian history, sagas, and folk ballads—Ibsen became the artistic director at the new Norske Theater in Christiania (now Oslo). He married the same year and with his wife, Suzannah, soon had a son, Sigurd. Sick of the repertory available to him—mostly French melodrama and light comedy by now-forgotten playwrights like Eugène Scribe and Mélesville—along with the endless fights about which dialects actors should use, Ibsen drank heavily and neglected his work. The only play he wrote while at the Norske Theater was Love’s Comedy (1862), set in contemporary Christiania, which caused the first scandal of his career. Critics denounced the play’s suggestion that love and marriage were incompatible as an attack on the institution of marriage itself, and rumors spread that the work reflected the Ibsens’ marital strife.

Ibsen later told a friend that, during this controversy, Suzannah was the only one who supported him. Suzannah would say that “the goal of my life” was to aid the development of Ibsen’s art, but living with him could not have been easy, especially for an intelligent and cultured woman like her. “Her obligations,” Figueiredo writes, “ranged from being an intellectually stimulating companion to putting him to bed when he was too befuddled by drink to do it himself.” Quite unlike his heroines who resist domestic shackles, Suzannah realized “whatever ambitions she may have had in life . . . through him.”

When the Norske Theater went bankrupt in 1862, Ibsen was blamed for its demise and fired. Unable to secure a writer’s pension from the government, in 1864 he moved with his family to Rome. Impoverished, deep in debt, dependent on friends to pay for his travel and expenses, he left his country a “drunken poet,” the future of his career uncertain.

The move was liberating; he wrote that he could now see “the hollowness behind all the lies and self-deceit in our so-called public life, and all those empty and wretched phrases.” By this point he had embraced a wider notion of Scandinavianism, dismissing Norwegian nationalism as narrow, isolating, and even backward. Brand was written in 1865, Ibsen’s annus mirabilis, driven by his anger at Norway’s failure the previous year to come to Denmark’s aid after it was attacked by Bismarck.

The preacher Brand demands “all or nothing” from himself and others, and, despite Brand’s inhuman coldness, Ibsen renders him as a kind of hero. Brand refuses to visit his dying mother because she won’t donate the money she took from his father, and he chooses not to seek medical care for his sick infant son because he has promised not to leave his flock. His wife dies of grief, but not before he reprimands her for saving their dead child’s clothing, which he refers to as “idols.” While leading his congregation into the mountains, they turn on him and stone him. In the end he is killed by an avalanche. (Ibsen was no Christian, but as Michael Meyer, an earlier biographer, noted, “For the last half of his life . . . Ibsen read little but newspapers and the Bible,” which, “he would hasten to point out,” he admired “for the language only.”)

Despite mixed reviews, Brand was an instant hit in Scandinavia. Georg Brandes expressed surprise at the “delicacy of consideration (and, apparently at least, of irony)” with which Norway welcomed the preacher’s censure of those who compromised their beliefs for the sake of conformity or comfort. Ibsen’s next work, Peer Gynt (1867), a stunning picaresque that lampoons Norwegian peasant life, provincialism, and greed, was also enthusiastically received. The assertion of its title character, a charming rogue, that his misdeeds are excusable because he has been “myself the whole of my life” sounds like a rebuke of nationalistic ideas that placed worth solely in the distinctiveness of a country’s land and people. Figueiredo attributes the play’s success to the way it captured “the spirit of the age”: “in the 1860s liberalism and belief in the individual had reached its zenith in Europe.” Indeed, both nationalism and individualism are the objects of Ibsen’s satire, but as he would do so often later in life, he denied that his motives were political: “If . . . the Modern Norwegian recognizes himself in Peer Gynt, that is those good gentlemen’s own funeral.”

Brand and Peer Gynt were closet dramas, meant to be read rather than performed (though both were put on during Ibsen’s lifetime); their success led him to write with a view toward publication rather than performance, in part because book sales brought significantly more income than fees from theaters. In addition to revenue from his publisher, Ibsen started receiving a pension from the Norwegian parliament in 1866. Not long before the release of Brand he had been voted the Roman Scandinavian community’s worst-dressed member, but, always vain when his wallet allowed, he soon bought an exquisite new wardrobe with his royalties. An acquaintance reported that Ibsen, apparently unsure of what to do with his money, kept large sums in his sock drawer.

In 1868 the Ibsen family moved to Dresden and remained, for the most part, in Germany until their return to Norway in 1891. Emperor and Galilean (1873), a sprawling two-part drama about Julian the Apostate, confirmed Ibsen’s status as Scandinavia’s leading writer. Ibsen’s Julian seeks to revive paganism, decades after his uncle Constantine introduced Christianity, in order to create a “third kingdom” that would transcend the limitations of each faith. Though the play was set, with exacting detail, in the fourth century, the struggles between Julian and his Christian subjects seemed to reflect contemporary debates about monarchy and democracy, and its philosophical discussions pitted faith against reason. “He is read with interest, indeed, almost hungrily,” one young admirer wrote. “Readers devour his books with an alacrity that is otherwise quite unknown in our domestic book world.”

After Emperor, Ibsen’s plays all had contemporary, bourgeois Norwegian settings, their drama consisting of the gradual and devastating exposure of secrets kept hidden by prejudices, hypocrisy, and unspeakable urges. It was these works, written with a European audience in mind, that made his international reputation. As A Doll’s House had, Ghosts (1881)—with its revelations of infidelity, syphilis, and incestuous desire in a respectable bourgeois family—caused a scandal. Conservatives denigrated Ibsen as salacious and intent on undermining all that was true and beautiful; others viewed him as a fearless truth-teller and prophet. Fans flocked to the towns where he summered, and newspapers reported every public appearance. Young women sought his company and Ibsen loved their attention, calling them his “princesses” and telling each that she reminded him of Hilde Wangel, a character who appears in The Lady from the Sea (1888) and, more fatefully, The Master Builder (1892). (Ibsen’s doting naturally infuriated Suzannah, who in 1895 was convinced her husband meant to leave her.) An acquaintance wrote that Ibsen presided over “the ministry of his own fame. . . . He took as much care in managing his name as his fortune.”

While he presented himself as isolated, cold, and unflappably dignified, in his work he often mocked his own reputation. Shaw noted that each play seemed to respond to the reception of its predecessor and subvert its apparent lessons. When Ghosts was published, the press demonized Ibsen as a muckraking crusader. Dr. Stockmann, the crusader at the center of his next work, An Enemy of the People (1882), tries to warn his fellow citizens that the water at their town’s spa is diseased, but the play at points borders on farce, and Stockmann is as motivated by spite, jealousy, and messianic delusions as by belief in scientific truth. Gregers Werle in The Wild Duck (1884) holds, as many thought Ibsen did, that “the claim of the ideal”—the recognition of ugly facts—outstrips all other moral considerations, yet his telling Hjalmar Ekdal that his daughter Hedvig may not in fact be his leads to the girl’s suicide and Gregers’s disgrace.

From 1882 until the end of the century, a new Ibsen play appeared every other December, in time for the Christmas shopping season, with translations released shortly afterward in English, French, Russian, Dutch, and German. “We had begun to think Ibsen immortal,” Beerbohm wrote. In 1900, not long after finishing his final play, When We Dead Awaken (1899), he had the first of a series of strokes that incapacitated him. He died six years later, his last words purported to have been “On the contrary,” though others said that it was “No!”

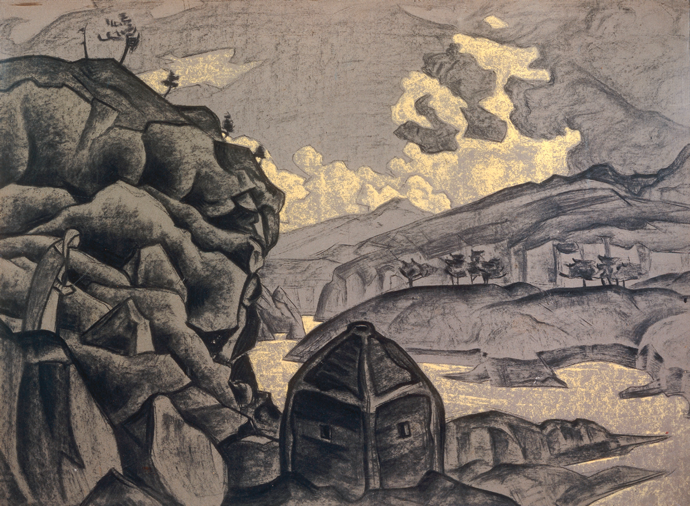

A drawing of the stage design for Peer Gynt, by Nikolaj Konstantinowitsch Roerich © akg-images

Figueiredo calls his biography, condensed from the original two-volume Norwegian version, “a book about Ibsen’s life, but . . . also a book about the myth of Ibsen that has taken shape over more than a century.” Many aspects of that myth, especially concerning Ibsen’s early life, were debunked by previous biographers. Figueiredo’s discussion of the plays feels almost perfunctory, and he makes a number of mistakes in summarizing them (Bernick’s mother, not Bernick, is responsible for the empty bank box in Pillars of the Community (1877); Dr. Stockmann’s brother is the town mayor, not the judge; “Resurrection Day,” the group sculpture that brought Rubek international renown in When We Dead Awaken, features not only women but also men, notably a self-portrait of Rubek himself).

Figueiredo’s analysis of critical interpretations of the plays sometimes gets so convoluted and vague as to leave the reader unsure what the author is trying to say. Reflecting on his subject’s monumental stature, Figueiredo writes, “The most important explanation for the success of Ibsen’s dramas is, in the final analysis, that they were written by Henrik Ibsen—and nobody else.” After some six hundred and fifty pages, this is a dishearteningly inane conclusion.

But despite the biography’s faults, Figueiredo has given English readers a superb account of the social and political atmosphere of Scandinavia in Ibsen’s time, and of Ibsen’s peculiar and inconsistent place within it. During the 1880s and 1890s, Norwegian politics was dominated by the introduction of parliamentarism and universal suffrage, as well as intense debates about dialect and the union with Sweden, but unlike his rival, the liberal writer Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Ibsen never allied himself with any particular political program (he did sign petitions in support of women’s rights and, out of concern for revenue from foreign sales of his plays, fought for international copyright protection). Ibsen’s political opinions were inconsistent. Sometimes he stated that democracy was the necessary means by which Norway could become an enlightened nation, once claiming that “the only ones I feel sympathy for are the nihilists and the socialists.” In other moments he expressed fear of the masses, though as Figueiredo points out, “we never hear him calling for ‘the strong man,’ and in all his work there is not a single example of a strong man who is not ultimately toppled from his pedestal.”

Ibsen’s only consistent political position, Figueiredo suggests, was his belief in a “spiritual aristocracy,” a “nobility of the spirit, the character[,] and the will.” “Democracy’s vital duty,” Ibsen wrote, “is self-ennoblement.” Whatever he meant by this, the answer suggested by his work is not what we would typically understand as “noble”—chivalry, self-sufficiency, selfless pursuit of an ideal. The phrases by which many of his characters understand their lives and justify their actions—Brand’s “all or nothing,” Stockmann’s “the minority is always right,” Gregers’s “claim of the ideal,” “human responsibility” in Little Eyolf (1894)—have a superficial appeal but are, like all mottoes, ultimately hollow. Yet they are still meant to be taken seriously. Their importance to the characters who utter them can’t be denied, even when they have pernicious effects. As Rebecca in Rosmersholm (1886), whose attraction to Johannes Rosmer is fatally intermingled with her dreams of social and political reform, says, “We are all only human.” The notion of nobility toward which the plays point, it seems, is one that requires acknowledging our striving and our weakness.

Though today the symbolism in his plays can feel belabored, the carefully plotted unveiling of secrets baroque, and the romanticization of suicide melodramatic, Ibsen was nevertheless a modernizer. When his career began, actors delivered their lines at the front of the stage facing the audience, and doors and windows were painted on backdrops. His contribution to the development of theatrical technique, Figueiredo writes, “was to liberate drama from . . . mimicry and superficial entertainment, turning it into part of the modern, contemporary world of art and communication.”

In his discussion of Ibsen’s contemporary reception, Figueiredo follows Toril Moi’s brilliant study Henrik Ibsen and the Birth of Modernism in showing how his plays, especially their female characters, challenged idealism, the dominant aesthetic ideology of the late nineteenth century. Idealists held that art should reveal the beautiful, the true, and the good, in order to uplift the spectator. The characters in Ibsen’s mature work who reject the human world in the pursuit of higher goals fail spectacularly.

“The ideal woman,” Moi writes, “is fit only for the role as ideal mother, ideal lover, tragic heroine, or supernatural muse.” As early as Love’s Comedy—in which Svanhild chooses to marry the wealthy businessman Guldstad, who promises her comfort and kindness, instead of the poet Falk, who sees her only as a means for inspiration—Ibsen depicted female characters who refused to sacrifice themselves. Nora tells Torvald that her “sacred duty” is to herself, not her family. She wants the freedom to act according to her own conscience, not the moral standards imposed upon her: “That a woman shouldn’t have the right . . . to save her husband’s life! I can’t believe in such things.”

In preparatory notes for A Doll’s House, Ibsen wrote, “There are two kinds of spiritual law, two kinds of conscience, one for a man, and one quite different for a woman.” Yet his insight was that women share with men the need to determine their path and to be acknowledged as thinking, desiring individuals. This didn’t always mean independence. One could choose marriage in good faith, but the choice had to be made freely, and the nature of the choice had to be acknowledged. Ellida in The Lady from the Sea ultimately decides to stay with her husband, but only after he grants the “freedom to choose” to leave him. Theirs is one of Ibsen’s very few happy marriages.

The critic Raymond Williams wrote that “the most persistent single theme in Ibsen’s whole work” is “the idea of vocation,” but this oversimplifies his ideas of self-fulfillment. To follow one’s vocation always involves subordinating others to one’s goals, as in the case of the feckless academic Tesman in Hedda Gabler, whose sense of vocation is so strong that he spent his and Hedda’s honeymoon conducting research into the handicrafts of medieval Brabant, all the while oblivious to his wife’s literally deadly boredom. Shaw’s view that Ibsen “insists . . . conduct must justify itself by its effect upon life” more accurately reflects the ways his characters, despite their confidence in their actions, fail to recognize others’ autonomy—“the miraculous thing” that Nora hopes for from Torvald but doesn’t receive.

But in life Ibsen seldom showed the respect he gave his characters. The Danish writer Laura Kieler, a friend of Ibsen’s, was the inspiration for Nora. Kieler did not leave her husband, who had her committed to an insane asylum when he learned of her forgery, and, as a result of the notoriety of A Doll’s House, she could never escape her association with it. The play, she later said, had “killed her soul.”

“As a man he was authoritarian, as a poet humble,” Figueiredo writes. In his work, at least, Ibsen did not provide artists any exemption from moral responsibilities. It’s tempting to view him indicting himself along with the sculptor Rubek in When We Dead Awaken. Rubek’s model, Irene, was the inspiration for and centerpiece of the group statue that brought him fame, but, unable to acknowledge the sacrifice she made for him by posing nude, he refers, crushingly, to their time together as an “episode.”

After the two meet again years later, Irene, who has had a series of loveless marriages and been institutionalized, tells Rubek that he “thoughtlessly took a warm-blooded body, a young human life, and ripped the soul from it—because you needed it to create a work of art.” She holds the cowardly and cynical sculptor responsible for the “fact that I had to die.” “Perhaps it is but another instance of Ibsen’s egoism,” Beerbohm wrote, “that he reserved his most vicious kick for himself.”