For time ylost, this know ye,

By no way may recovered be.

—Chaucer

I spent thirty-eight years in prison and have been a free man for just under two. After killing a man named Thomas Allen Fellowes in a drunken, drugged-up fistfight in 1980, when I was nineteen years old, I was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. Former California governor Jerry Brown commuted my sentence and I was released in 2017, five days before Christmas. The law in California, like in most states, grants the governor the right to alter sentences. After many years of advocating for the reformation of the prison system into one that encourages rehabilitation, I had my life restored to me.

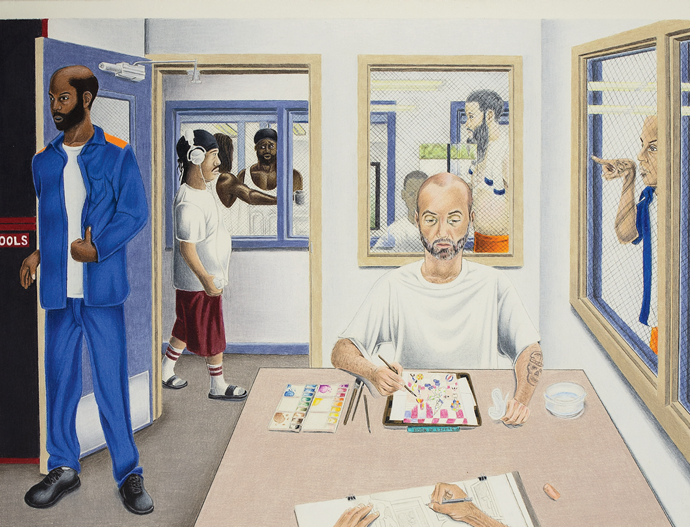

The Painter: A Portrait of Prison, by Christopher A. Levitt © The artist

Courtesy the Prison Creative Arts Project at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

When I first got out of prison, I was confronted by a society that knocked me off balance for months. As my perception began to right itself and I was able to take stock of my situation without being blinded by the glare of the new and the amazing—self-driving cars and handheld supercomputers in everyone’s pockets—my deficiencies became more apparent. They ranged from the mundane—no job, no housing, no retirement plan, and no obvious way of acquiring any of these things—to the more profound—no history of meaningful relationships, no easy way to be honest about my past, no real experience of the confusing realities of life as an adult. Every day I’m reminded how far outside the course of normal human existence my life has been. Every time I think I’ve made great progress, I’m confronted by a personal interaction that goes awry for reasons I don’t fully comprehend.

I wanted to know how the experience of returning to the world is perceived by other former long-term denizens of the house of many doors. My own wonder at the panoply of choices on a restaurant menu, or my dismay at the legions of homeless people overlooked on city streets, leaves me breathless at times. Was this the norm?

Susan Bustamante served thirty-one years of a life sentence without the possibility of parole for killing her abusive husband until Governor Brown also commuted her sentence. She was released on September 12, 2018, and I spoke with her five months later. She is now sixty-four years old and lives in Azusa, California. As a fellow former life-without-parole prisoner, I want to know whether she feels as I do about the experience of sitting in prison waiting to die, living without hope of release. I can hear in her voice the utter astonishment at being free, at not dying in prison.

On the day she was released, she tells me, her supporters and her children, some of whom had come hundreds of miles to celebrate and embrace her, waited outside the front gate of the California Institution for Women. Traditionally, in California, paroled lifers are allowed twenty-four hours to report to their parole agent after being picked up by family or friends: time for reunion and reconnection, to purchase new clothes, get a decent meal, or just to go to the beach and feel the salty embrace of the Pacific Ocean.

Bustamante and her loved ones were not afforded that grace period. The transition program to which she was assigned has a policy of taking its new charges directly to the parole office and then allowing for a much shorter period of family reunion time later that day. For unclear reasons, possibly miscommunication, Bustamante was not informed of this direct transport.

“My daughter drove twenty-two hours straight from Missouri with her family to get here, to then not get to see me when I walk out the gate, which was their right, after thirty-one years. They were eight and eleven when I came to prison,” Bustamante tells me.

She then had to report to a near-lockdown facility that restricts cellphone and computer use, limits contact with family and the rest of the outside world, treating inmates as if they’re incompetent.

Bustamante’s story is all too common. It’s a growing pattern in the criminal-justice system’s parole arm—transitional housing, often set up by private-sector organizations, that is not well suited to the needs of paroled lifers. At the program to which I was assigned after my parole, one of the facilitators told me that my twenty-eight years of sobriety meant nothing because I had been incarcerated during all of that time. My life inside was deemed not real at all. The program focused on the amorphous and indefinable concept of “criminal thinking” as the locus of all problems experienced by parolees. This was pounded into us so often, with such inflexible zealotry, that in several of the classes I had to attend there were revolts from the lifers in attendance. All of us had been taking rehabilitation classes for years; many of us had been facilitators ourselves. We knew that our experiences inside had been real and that they mattered.

After six months of living in this overly restrictive halfway house, Bustamante moved in with a family member, one of the people who had been disappointed outside the gates at the prison. She is a woman with practically zero likelihood of committing another crime and returning to prison. Nevertheless, she will be subjected to the same set of limiting and humiliating restrictions as those who are in much higher-risk groups.

Bustamante is one of the many parolees I’ve spoken with who possess a tremendous desire to give back, to remember the folks they left behind, the people they formed decades-long relationships with and miss every day on the outside. There is ferocious compassion and empathy in her voice, an intense maternal quality.

“Any help that I can be I am willing to be. I am just so wanting to keep the momentum of forward progress even if in some way I get [California governor Gavin] Newsom to get more commutations done. Because there’s so many people that are deserving to be out. You know we have an eighty-year-old woman that has been [inside] for over forty years. Come on now.”

Even though Bustamante was lucky to end up with a good parole agent, for the next three to five years she’ll be forced to seek permission to travel outside the county where she lives. At least once a month, she’ll be required to provide proof of residence and a urine sample.

When I was newly released from prison and had to report to my parole office, five parole agents ago, I was startled to meet a man who shook my hand and said, “My job is to help get you off parole as fast as possible.” He would go on to encourage and champion me and help me build self-confidence, though, in the thoughtless machinations of the prison system’s bureaucracy, he was transferred out of the lifer-parole assignment.

Our nation’s prisons hold tens of thousands of men and women who have served for far too long. Whatever lesson they could have learned was learned years ago. These are old men and women who do not resemble their young selves in any way. Holding them until they die is cruel, expensive, and pointless.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate and the largest total number of human beings imprisoned in one country. About one out of every thirty-seven adults is under some form of correctional control—not an insignificant number. Poor communities, and poor communities of color in particular, have been decimated. We have created an industrial system of locking people up for very long periods of time. And we have institutionalized a punitive approach that boasts of its cruelty and the wanton infliction of pain, that sets out to break and crush, and that has succeeded in this dubious effort all too well.

Our country has continued to embrace the idea of using force to solve social problems long after other democracies have abandoned that approach as inhumane and counterproductive. The harsh treatment of prisoners follows them out of the prison gates. One California reform organization, Root & Rebound, has identified more than forty-eight thousand legal and regulatory impediments designed to punish and hinder those who have served time. These include everything from rules preventing former prison firefighters from becoming firefighters in the free world, to restrictions on government housing, to bars against professional licensure in fields as diverse as cosmetology and scrap metal processing.

There is something uniquely unforgiving about the United States that is a product of our history—indigenous genocide, slavery, Puritanism, colonialism, capitalism, racism, sexism, xenophobia, and homophobia. But just as the past decade has seen a broad reassessment of this history, there has been a similar rethinking of the tough-on-crime approach advocated in the 1980s by conservative critics of rehabilitation such as James Q. Wilson, the originator of the Broken Windows theory of policing, and accelerated in the 1990s by criminologists such as John Dilulio, who coined the infamous term “superpredator.” We have begun a slow march away from the approach of punishment for the sake of inflicting pain.

The United States holds about 40 percent of the world’s population of prisoners serving life sentences—more than 160,000, including more than 50,000 who are serving without the possibility of parole—thousands who have been sentenced to life terms for nonviolent crimes, and an additional 45,000 people who have been sentenced to de facto life terms of fifty years or more.

Specific statistics for the lifer population are hard to obtain, and what information is available is fragmented. A recent Justice Department report found that nearly a third of state prisoners sixty-five or older were serving life sentences. In California, the release of lifers has increased dramatically in the past ten years, and many older, long-serving prisoners are being set free. Some of them have served more than four decades for crimes committed when they were teenagers. They will enter a society that is so different from the one from which they were removed as to be like another planet.

In the past fifteen years, the U.S. Supreme Court has issued a series of groundbreaking decisions that affect sentencing for juveniles. In 2005, Roper v. Simmons banned capital punishment for those under eighteen. In 2010, Graham v. Florida prohibited sentencing juveniles to life without parole in non-homicide cases. In 2012, Miller v. Alabama outlawed mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles in all cases. And in 2016, it made that ruling retroactive in Montgomery v. Louisiana, giving older prisoners who were sentenced as teenagers hope for release.

Most criminologists believe that just about anyone over the age of forty is not much of a risk to society, even those who committed violent crimes in their youth. Statistics and scholarship bear this out. There is a very strong correlation between age and the risk of offending. Supporters of the tough-on-crime approach, however, see this correlation as proof that decades-long periods of imprisonment do work. In their view, that’s why the recidivism rate for paroled lifers is as low as it is.

Thing About the Future, by Dwan Chatman © The artist

Courtesy the Prison Creative Arts Project at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Albert Lewis spent most of his life inside one of the most notorious prisons in the world: Louisiana State Penitentiary, more commonly called Angola. When I meet him I am taken immediately by his calm and peaceful nature. Lewis comes slowly out of his house in the shadow of the earthen dike that contains the salty waters of Lake Pontchartrain in New Orleans. He’s wearing a pair of patched blue jeans, a white sweatshirt, and a black baseball cap. His black, plastic-frame glasses are thick, leaving a dent on the bridge of his nose. He smiles easily, his initial reticence disappearing in the realization that we both walked the yards, if not together. Lewis served forty-two years after being sentenced to life at the age of seventeen.

He speaks in short and concise sentences that express his feelings with simple eloquence. He has a relaxed posture, his shoulders resting easily. The time he spent confined to that former slave plantation with more than five thousand other human beings—a prison in its most elemental and revanchist form—had not hardened his heart.

We eat breakfast in a little café on a lively side street in one of the city’s gentrifying neighborhoods. Lewis is blind in his right eye and has serious glaucoma in his left. While still in prison, he noticed that he was losing his vision and complained to medical staff. Two years of inaction later, he was taken to see a doctor and diagnosed with advanced glaucoma. After being released, he was treated for a long-term case of hepatitis. At fifty-nine, he moves more like a man in his late sixties, with an obvious stiffness and regular grimaces of discomfort that I, too, experience. Between the two of us we served eighty years inside. We suffer from ailments common to those much older than we are. The big, colorful menu, challenging to me in its impressive array of choices, stymies Lewis and his limited vision. With some assistance, he orders a simple plate.

“The best thing that has happened to me since I got out was saying hi to my mother [and] my niece. We stay together; she takes very good care of me. Other than that, I’m living, thanking God for my freedom. I’m blessed. People tell me every day that I don’t act like a person who went to prison for forty-two years. It seems like I never left, the way that I’m adjusting. So I’ve got to say that all the problems that I have, it’s work and financial, but other than that, family support gets delivered here and there, and I’m fine.

“Sometimes I come out and walk. I’m just amazed at how people accept you. People don’t worry where you come from; it’s who you are today. You know, you show me that you’re a man of God and respectful, then we love you, and I give that same love and respect back. And I can get along with everybody; I can go anywhere. I love kids. I can be with kids everywhere I go—it’s just been great. I feel really great about my future, because no matter what, I’m not looking back and I’m not ever going back to prison. I’m looking straight ahead. And I know that one day something’s going to give, if it isn’t any more than Social Security, it’s going to give, and I’ll be able to do things the way I want to, and it’s going to be good.”

After breakfast, we take a walk down the street to a pedestrian bridge over the dike, to a little park at the Mississippi River’s edge. Oceangoing freighters are plying their way back to the Gulf of Mexico; families are out walking their dogs. We pause at the apex of the bridge before descending back down to the street.

Lewis says, “When I got out, I wish that I was able to function normally, to be able to help myself and to help those, like my mother and niece, who had helped me the whole time that I was in prison.

“It’s hard for me to get a job. I have skills, but due to my blindness I can’t get a job. So I’m waiting on Social Security”—disability benefits. “I filed for it. It’s been about seven months now. I’ve seen the doctor, and I’m still waiting to hear from them,” Lewis tells me in an understated tone that belies the importance of the concern—one many of us on the outside share. We have no retirement savings, nothing of monetary value, no Social Security contributions, and very limited access to health care.

“I’m hoping one day I’ll be able to get me a job, make things right, so I can do a bit of traveling. That’s what I really want. I want to see something rural. I’ve never been anywhere. I went from home to Angola and that was it, you know. So I think it would be really nice to get away for a while. Meet people on the outside of New Orleans. Think it would be great. I would like to see more people come out of prison. Because there’s a lot of people that deserve their freedom. There’s a lot of people that haven’t really committed any crimes, [they’re] just victims of circumstances. And they don’t deserve to serve as much time as they did. Just like me, you know, I went to prison, I didn’t commit the crime, but I was there with the guy. And they said that I had had knowledge of the crime, I didn’t notify authorities or family members, so it was just like I was the triggerman, and that cost me forty-two years of my life.”

What Lewis tells me should shock me, but it doesn’t. I’ve heard variations of this story too many times. Maybe I am too close to this, maybe after decades of being treated as less than human, it seems normal to me.

Before I leave the state, I learn that parolees in Louisiana have to pay a monthly bill to the parole system. While I had never heard of such a practice, I’ve come to learn that these so-called supervision fees are quite common around the country. Forty-four states charge fees for parole and probation. The proceeds from the fees are used to fund probation and parole departments’ budgets. Lewis’s forty-two years of punishment apparently weren’t enough to square his debt to society; he must also pay $63 a month, driving him further into penury. If he can’t afford to pay today, the debt will be rolled over and added to his burden. And he’ll be on parole for the rest of his life, as are most paroled former lifers, even in California.

In Indianapolis, I speak with Professor Jody Sundt, a tenured criminologist at Indiana University. She is a tall, elegant, soft-spoken woman with a musical voice who understands my world better than I could understand hers, and is one of only a handful of criminologists I’ve ever met who seem to truly appreciate the lived experiences of prisoners. It’s a rare thing for anyone who hasn’t been a prisoner to comprehend what serving time is actually like, and, in my experience, it’s hardest for criminologists. Maybe they’re burdened by their theories, maybe it’s something else. But when Sundt and I first meet, I feel an instant connection.

She affirms the generally held assumption in the criminology profession that prisoners in their forties are no more dangerous than most forty-year-olds in the rest of the population and that after about eighteen months of successful parole, most parolees don’t actually need to be on parole. She also believes that parole operates on “an assumption of control,” that it’s “designed to further the sentence,” and that “it’s not prevention-oriented.” The focus is rather on “compliance with rules” that are based on an “outdated concept that prison changes people,” she says.

Sundt’s message is that “there is a terrible loss of human potential” in the long-term sentences of the retributive model this country relies on in its criminal-justice system, and this strikes the deepest chord with me. In my thirty-eight years inside, I watched the prison system devolve from one that made half-hearted attempts at rehabilitation into one that is purely punitive. There is nothing of merit in the current approach. It does not serve society well, and it fails in its most important responsibility, protecting human beings.

Sundt sums it up toward the end of our conversation: “Deterrence seeks to make the punishment so certain and severe that nobody would choose to re-offend, but it usually fails. Rehabilitation is the only philosophy of crime control that focuses on addressing the causes of individual recidivism.” In other words, the purpose of a rehabilitative system is to help the offender not to commit future crimes. The current retributive model focuses only on punishment for past crimes.

Then Sundt takes me to a basketball game, despite a powerful ice storm that has closed down much of Indiana. By the time we make it to Purdue University’s basketball arena it’s halftime. The feeling inside that massive dome of cheering and jumping is pure Midwest. It is almost too innocent to believe, the cheerleaders in their modest skirts and the unattended coatracks, the lack of fistfights; it is like a college game in another time, long ago.

Philadelphia has a long history of political organizing and struggle. This is the site of the infamous police bombing of a residential home tied to the black liberation movement that burned down more than sixty row houses and killed eleven people, including five children.

I am here to see Robert Saleem Holbrook, with whom one of my oldest friends in the prison-reform struggle, Noelle Hanrahan, had put me in touch.

Holbrook meets me at the door to an office in an unnumbered building in a neighborhood that looks to be simultaneously falling apart and being rebuilt. He is dressed in boots and fatigue pants below a colorful sweater. His eyes are intense and aware, and he moves quickly and confidently. Now forty-five, he spent twenty-seven years in prison before being paroled in February 2018.

Holbrook’s office is spartan. There are posters and photos honoring the long struggle for justice. The wall calendar is marked up with meetings and rallies far out into the coming months. Holbrook himself exemplifies the furious energy and focus of many formerly incarcerated men and women I’ve come to know since my release. We are all constantly reminded of what we’ve missed. For some, like Holbrook, the reminder provokes resistance.

I ask him what has most surprised him about the world out here. “My neighborhood was gentrified. Much of Philadelphia is being gentrified, so the racial demographics have changed. Neighborhoods, like the suburbs of Philadelphia, that were once all white now predominantly are black, because people from the city moved out. So it’s just flipped. For me that was just kind of the weird thing, like walking down this neighborhood like, ‘Damn I used to have to run through this joint, now it’s a coffee shop.’ You know what I mean? I don’t even know how to process it.”

I ask him whether he believes the prison system prepared him for parole.

“No,” he says. “I prepared myself. I took the initiative when I was in there to get into all the programs available. For me, I had to make that change because, as someone serving life without parole, I was at the bottom of everything. So programs and stuff like that were not available. Now, as much as this is against every fiber of my being, I’ve got to give the Department of Corrections some credit. Once Miller was ruled retroactive by Montgomery, they kicked things in gear and gave juvenile lifers priority to get in programs. And I took full advantage of that. I jumped into every program that was open: HVAC, computer training, and paralegal studies, all of the programs that I was previously denied. However, before that, before those programs were available to me, I took correspondence courses. I placed a high priority on education. And a lot of that was the support system I had on the outside, and also my personal inclination to change.”

When Holbrook speaks, he often pauses for a moment, weighing his words, making sure he’s saying exactly what he wants to say.

“I wish I would not have come out so hard-charging. I wish I would have come out and just said, ‘Hey, look, let me spend more time with my family.’ So I wish that the first couple of months I would have devoted more time to my relationships.” As I leave, Holbrook fields calls and prepares for his fourth meeting of the day, practically vibrating with righteous energy.

Sara Norman is an attorney who for the past two decades has worked at the Prison Law Office, which has been at the forefront of litigation against the California prison system since 1976, fighting for the improved treatment of the mentally ill as well as the developmentally and physically disabled, for the provision of adequate medical care for all prisoners, and for the reduction of overcrowding. After a string of amazing victories, all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, the office is nothing short of legendary inside the state’s prisons.

I ask Norman about the parole system. She recounts some of the cases she’s been involved with, like that of a prisoner named Gene Horrocks, a wheelchair user, who, in 1995, was forced to crawl up two flights of stairs to get to a Board of Prison Terms hearing; that of Clifton Feathers, legally blind and terminally ill, who, in 1997, was denied parole because he had “failed to develop a marketable skill that can be put to use upon release”; and that of Elio Castro, a deaf man with profound developmental disabilities who, in 1996, was denied parole and directed to participate in Alcoholics Anonymous programs without an interpreter.

Norman says, “Prison in this state, in this country, is figured in people’s minds as a place for punishment where bad people go, and suffering is okay because they’re bad. And that is wrong in every possible way. Until we look at the full spectrum of options available to us when somebody is found to have committed a crime, with a laserlike focus on doing what works and what makes all of us safer and what heals people, we won’t have a system that has any degree of humanity. The prison system, as it’s figured now, is about punishment and harm, and to some extent about harm reduction, about removing people from the streets who can harm other people. But it’s not about working with them to become productive members of the community when they’re inside. It is a little about that, but that’s not the dominant strain, the dominant focus. And until it is, then you can’t talk about a parole system that appropriately reflects what will keep us all safe. We’re talking about a profoundly imperfect and damaging prison system.

“Parole should recognize that you can’t blame people for not doing programs when they don’t have programs. Does that mean you should just let them out? I would say yes. Others would say no. But I think if I were a parole commissioner, and I were hearing cases come before me, I would say I cannot in all conscience [make a decision] because you are not giving them the programs that they need to succeed.”

I tell Norman that one of the reasons I think the Progressive Programming Facility, where I spent time, has done so well for people like me is that there were guys who could say that they’d done many programs and demonstrated that they had made an effort at rehabilitation. The prison system doesn’t actually rehabilitate anyone; we rehabilitate ourselves. But I am telling her something she already knows.

“We are all a human community,” says Norman.

Northern Flicker, by Luis Norberto Martinez © The artist.

Courtesy Community Partners in Action Prison Arts Program and The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Connecticut

After an hour-long train ride through the industrial parts of Oakland, California, down into the southern Bay Area’s suburban neighborhoods, I’m sitting in the largest Starbucks I’ve yet seen. Timothy Long walks in dressed in a plaid shirt and jeans. He is a large man who exudes stability and spends his days teaching adults in a school in the East Bay city of Menlo Park. I was given his name by Emma Rosenbush, a managing partner of Cala, a celebrated San Francisco restaurant that hires the formerly incarcerated, where Long worked when he was first paroled.

We see each other before his text reaches my phone, the instant recognition that I also had with Albert Lewis and Robert Saleem Holbrook. Long has been out for more than two years, having served twenty-six, and he’s doing well. After looking around for a quiet place to talk, we decide to sit in his car. He’s a sturdy man, broad-shouldered and muscular, with an obvious confidence. He reminds me of a football player. I comment on his Dodge, the odd American car in a parking lot full of Toyotas and Hyundais. He shrugs. “Of course, I’m from Detroit.” Like most everyone else I’ve met while reporting this story, he’s hopeful and energized.

“My biggest surprise is that no one actually knows my past. They can’t look at me and just see ‘convict.’ If I tell people my past, they’re like, ‘You’re kidding. Not you!’ because I just don’t have that look,” Long tells me. “My current girlfriend always says she wonders why I’m not always mad or upset that so many years have gone by. I’ll be like, there’s nothing to be upset for because I accepted my responsibility for what put me in prison. And once you get to that acceptance, everything else is a really easy walk.”

Did the prison system prepare him for parole? I ask. “The system as it is structured? No. I would say I prepared myself, mostly because I knew what it would take for me to get out, and just by what the prison system wants you to do. They don’t actually show you how to become accountable for your deeds, though that’s what they want you to do. So that is something that you must find within yourself, and that’s what they don’t do.”

I ask him how he’s been treated on parole. “San Francisco, and this parole department, they look for ways to keep you out of prison, they look for ways to make sure you’re just doing all right. They don’t go out of their way to find nitpicky stuff to lock you back up. And I know some guys who violate it, but instead of sending them back to prison they send them to a drug facility to get sober. Everybody doesn’t have an easy time getting out. This one particular guy, his wife died two weeks after he got married, and he relapsed.”

I ask, “How are they on travel passes—any problems, or have you asked for them?”

“I’ve asked, and I ask often, because my entire family is in the Midwest, so whenever I want to go back, which is generally a couple times a year, I’ll ask. And I’ve only had one problem, and that problem was with a parole officer that I had for a short amount of time. I just think she didn’t like my job, she didn’t like my car, my girlfriend.”

I tell him, “It was too much for her. You were doing too good; you’re not supposed to be doing that good.”

“Basically, my life is an open book now,” Long says. “Anyone who wants to see my record, they can just look my name up. It will just come up in big bold letters. But I am thankful of everyone that just accepts me for who I am today and not what I did in 1989. I was also thankful that even the victims of my crime who spoke up at the parole hearing . . . it was like, ‘He doesn’t seem to be the same person he was then.’ ”

I ask about teaching as a formerly incarcerated person—does the school tell the students? “They don’t tell the students,” he replies. He taught at one place called BOSS—Building Opportunities for Self-Sufficiency—where most of his students were either on parole or probation. “A lot of them were gang members and what have you. So, I went in there. I mean, these are hypermasculine dudes, so you have to go in there knowing what to expect. You have to give that same, and I can be the toughest guy if I want to be, but I didn’t do that. I went in there being myself, and I told them what my background was, and I told them how I got out of that cycle of bullshit. And they were like, ‘Damn, if he can do it, maybe I can do something else. Other than just walking around trying to sell drugs, or keep a pistol in my pocket, or whatever.’ Because I know what that path is going to lead to, and they know what that path is going to lead to, but they think they don’t have any choice.”

I ask Long, from his experiences, whether people like us are valuable in the role of teaching young people in tough circumstances. “Definitely we are, because we know the path already. We see the end result. A lot of programs we took in prison taught us to see the repercussions of our actions. If we can just instill a little of that in them, it may prevent them from pulling that trigger, or doing something else stupid that will end up with them getting locked up for life for whatever. I was a speaker at a graduation, and five hundred people were there. The graduating class, all their families, and that’s what I talked about. My past. And how I got out of there and how education will help them avoid that cycle.”

I ask him what’s been the worst thing that has happened to him since he got out. “I got married, and then I got divorced. I got married because it was with the young lady I was with for the majority of the time that I was in prison, and she was a good woman. But I found out after I got out that she liked the structure of me being in prison, that she always knew where I was every minute. She knew what time I would eat, what time I would go play basketball, what time I would work, what time I would have to go to bed. And she liked that, and she tried to keep me in that box. So the marriage didn’t work because I’ve been in a box for too long.”

I comment on the success I’ve seen, even among those damaged by the system. “Maybe most of us who get out are actually doing well, regardless of the experience,” Long says. Data on this issue is limited, but the Stanford Criminal Justice Center found in one study that fewer than 1 percent of paroled lifers return to prison, as opposed to more than half of California’s parolees overall.

My daughter, Alia, the happy outcome of a conjugal visit before such meetings were disallowed during the low point of the tough-on-crime Nineties, lives in San Francisco. Since I was paroled, we’ve struggled to develop a different relationship outside the constricted but certain one we built while I was slated to spend the rest of my life in prison.

On my last day in the city, I have breakfast with her in a colorful diner close to the train station in the Mission District. I can still remember her as an infant, her tiny body fitting against my forearm, her head nestled in the palm of my hand. Now there is a well-dressed, vibrant young woman sitting across from me, with the clear outlines of her mother’s beautiful face becoming more evident. As she settles onto her stool, we exchange pleasantries about her work and school. I am almost overcome by emotion, I choke up at the sheer normalcy of this moment after all the years of seeing her inside the cold, sterile confines of a visiting room.

For an hour we talk about our lives, hers revolving around friends and roommates, mine around fitting in and finding out what it is to be an adult in the world. When I was still inside, she would joke that I was forever a nineteen-year-old, my life frozen at that age, my emotional development stunted.

When she heads off into the city, to a college class, I watch her disappear down the stairs to the train. I’m glad she’s growing up and has her own life, but I mourn all the missed years, blacked out entries in a faded logbook.

When I first got out, my friend Linda Hornbek took me to a store to buy clothes. After about an hour of looking through what seemed like miles of racks and bins, I had accumulated a small collection of shirts and pants. With a hand on my shoulder and a smile on her face, she looked at me and said quietly, “You know, these are a lot like the clothes you’ve been wearing for the past thirty-eight years.” I hadn’t noticed.

The second place I went after I was released was a Verizon store. The choices were overwhelming. I only knew two things: I wanted a phone, and it had to be an Apple so that my daughter and I could use FaceTime. When the young salesperson approached me, I asked how much memory I should get. She wanted to know how much I had in my current phone. I told her I didn’t have a phone, that I’d never had a phone. She looked puzzled, so I leaned a little closer and told her that I’d just gotten out of prison and how long I was there. There was a flicker of hesitation in her eyes, and a beat or two passed before she leaned toward me and said, “You won’t need much memory then.”

The early interactions I had were uniformly positive, though I know that’s not every parolee’s experience. I’ve seen old friends who live in apartments that look like prison cells, and I’ve talked with guys who tell the same tired war stories they told back in the yard. They are still trapped by the brutally enforced codes of honor we followed inside—rigid honesty, ritualized respect, and intensely held secrecy—but the outside has neither the ability to comprehend nor the interest in learning about our lives in prison. I believe there are many variations of these men and women now living outside the prison system, irreparably damaged by their years inside. And while they pose no threat to anyone, they also have little fulfillment or happiness.

I’ve met a lot of successful parolees, but out of the spotlight trained on those stories, there are many more men and women who live lives characterized by loss—loss of a sense of place, loss of a future, loss of family and friends, and loss of dignity. These people are compelled to seek handouts from their families (if they still have any) or the government to survive. They are not well trained for the modern workforce. They leave prison without the ability to navigate the complexities of the digital world. They can’t even find their way around a smartphone. I’ve seen them in group therapy classes and gatherings at the parole office, dressed in baggy clothes, looking startled and confused, their unease shadowed on their faces. They have the haunted look of soldiers with P.T.S.D. They have undergone a kind of trauma that’s hard to describe and harder still to survive.

There are those who still believe that punishment is all that matters, that people who commit serious crimes should be made to suffer. What these people don’t seem to realize is how profound and counterproductive the level of suffering inside our prisons is. For many, the punishment never ends. They are condemned to be imprisoned for the rest of their lives, even after they get out.