The WASP story is personal for me. I arrived at Yale in 1971 from a thoroughly mediocre suburb in New Jersey, the second-generation hybrid of Irish and Italian stock riding the postwar boom. Those sockless people in Top-Siders, whose ancestors’ names and portraits adorned the walls, were entirely new to me. I made friends with some, but I was not free of a corrosive envy of their habitus of ease and entitlement.

Franklin Roosevelt (front, second from left) with the Groton football team, 1899 © Bettmann/Getty Images

I used to visit one of those friends in the Hamptons, in the 1970s, when the area was about wood-paneled Ford station wagons, not Lamborghinis. There was some money in the family, but not gobs, yet they lived two blocks from the beach—prime real estate. Now, down the road from what used to be their house is the residence of Ira Rennert. It’s one of the largest private homes in the United States. The union-busting, pension-fund-looting Rennert, whose wealth comes from, among other things, chemical companies that are some of the worst polluters in the country, made his first money in the 1980s as a cog in Michael Milken’s junk-bond machine. In 2015, a court ordered him to return $215 million he had appropriated from one of his companies to pay for the house. One-hundred-car garages and twenty-one (or maybe twenty-nine) bedrooms don’t come cheap.

Milken’s machine helped break apart the old Wall Street, the one of clubby partnerships, where whom you knew at St. Paul’s mattered more than whether you could pull off a leveraged deal or snooker the guy on the other side of a trade. Taking their place were the masters of the universe Tom Wolfe made famous, and profit maximization was their prime directive. The combined destructive forces of a highly valued dollar and the takeover mania of the 1980s helped do in the old manufacturing companies that were the economic base of much of the WASPs’ financial power, which had already taken serious blows in the inflationary bear markets of the 1970s.

In economic language, the transaction replaced the relationship—not just on Wall Street but in American business generally. And the same can be said of the elite as a whole. WASPs once made for a fairly coherent upper class: concentrated in big cities and their suburbs in the Northeast, products of the same prep schools and colleges, likely to choose from a small pool of marriage partners, guaranteed of a decent inheritance and, for men, a sinecure at a respectable firm. Social ties were stable and for the ages. That has all given way to rule by money. Now you have to pay a consultant half a mil to get your kids into U.S.C. instead of relying on your bloodline to get them into Harvard.

When George Herbert Walker Bush died, a standard feature of the memorials was to celebrate his Waspy virtues of modesty, considerateness, and public spiritedness, in sharp contrast to the bombastic fool who occupies the Oval Office today. Ross Douthat opined that we miss those things because they signified a “ruling class that was widely . . . deemed legitimate.” It’s a thought I’d had before. Honestly, it is a little tempting to get sentimental about the old order. Next to the reigning crassness of our day, that sort of reticence has a seductive allure. But it’s distressing to find yourself agreeing with Douthat, even in passing. How valid is the sentiment? And how well can our system live with an elite as rotten as the one we have?

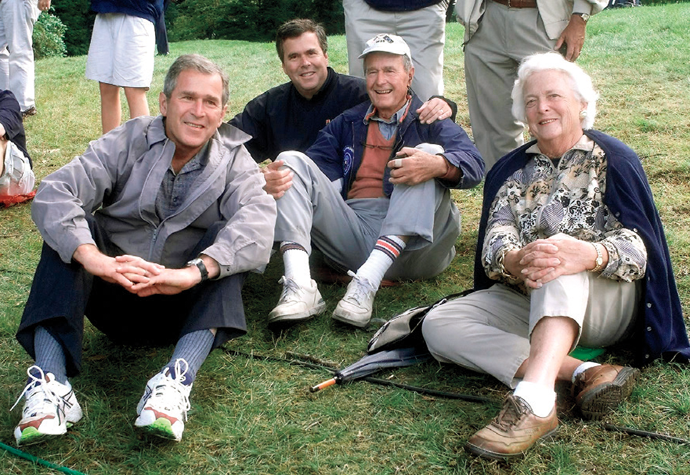

The Bush family at The Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, 1999 © John Mottern/AFP/Getty Images

Though the early United States was settled and ruled by WASPs—assisted by their disreputable cousins, the Scots-Irish, who did the dirty work of killing Indians and capturing runaway slaves—the formation didn’t come to consciousness as a group until the late nineteenth century, with the onslaught of immigrants from the less respectable corners of Europe. As the caste’s most prominent sociologist, E. Digby Baltzell—himself a product of Main Line Philadelphia—shows in his book The Protestant Establishment, published in 1964, that’s when a set of institutions central to WASP identity were founded. (Baltzell is credited with popularizing the acronym for “white Anglo-Saxon Protestants,” though perhaps the first published mention of the term, attributed to “the cocktail-party jargon of the sociologists,” was by the political scientist Andrew Hacker, in 1957.) Baltzell identifies several milestones from the late 1870s and 1880s: Harvard president Charles Eliot built his summer retreat in Northeast Harbor, Maine, inaugurating the summer resort fashion; a group of Boston gentlemen with a taste for golf founded the Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, kicking off a national trend; the Sons of the Revolution was established, marking the onset of an obsession with old-stock roots; and the Social Register, the definitive catalogue of those who mattered, published its first issue.

Most importantly, in 1884 came the founding of the Groton School by Endicott Peabody, whose aim, in the words of the school’s official history, was “to instill high-minded principles in the offspring of the most successful American entrepreneurs of the Gilded Age.” There were private academies before—the Phillips duo, Andover and Exeter, date to the late eighteenth century—but Groton and its spawn such as Choate were more consciously part of a class-separatist project. Groton’s motto is Cui servire est regnare, which is conventionally translated as “To serve is to rule,” though the school prefers the less imperious version, “For whom service is perfect freedom.” Grotties don’t want to own and run things really—it’s just a burden they take on for the general good.

Peabody, who remained headmaster for fifty-six years, modeled the school on his experience in England: austere and rigorous, driven by the doctrines of “muscular Christianity,” which revered duty, sacrifice, discipline, manliness, athleticism—and imperial adventure. In his 1901 book on elite English schools, James George Cotton Minchin celebrated the image of “the Englishman going through the world with rifle in one hand and Bible in the other,” observing, “If asked what our muscular Christianity has done, we point to the British Empire. Our Empire would never have been built up by a nation of idealists and logicians.” In that tradition, Groton has given us generations of imperial managers and spies (though occasionally spiced up with the likes of Fred Gwynne, best known as Herman Munster).

Peabody’s muscular Christianity reflected elite anxieties at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries around a loss of manliness and a spreading neurasthenia compared with the rougher pre-industrial times. That flabbiness was countered at Harvard, as scholar Kim Townsend shows in Manhood at Harvard, with an intensified emphasis on sports—a project that Yale had taken the lead on. The rivalry between the two schools was in no small part an exercise in establishing a combative, if gentlemanly, masculinity.

Suspicions as to the masculinity of elites never went away. During the McCarthy era, a “Lavender Scare” was prosecuted alongside the Red Scare—a purge of a thousand alleged same-sexers in government, particularly the State Department. Both witch hunts focused on the posher sorts who populated the Foreign Service in those days. Decades later, Richard Nixon, who cut his political teeth on those twin purges, was heard on the White House tapes observing that “the American upper class now has become like the British upper class, or much worse, I should say like the French upper class was before World War II: decadent, incestuous, homosexual.”

When the rude masses began arriving from Eastern Europe, the WASPs got paranoid that they were, to use the phrase chanted by the rioting Nazis in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017, about to be “replaced.” They turned on their former class siblings, the German Jews, with whom they’d once shared the upper rungs of American society. As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth, many old-line WASPs embraced a toxic mix of social Darwinism and eugenics.

Not all did, of course; some eventually found their way into the Progressive movement (though Theodore Roosevelt, a leading “Progressive,” was anything but a paragon of racial enlightenment). But the late-nineteenth-century American upper class largely delighted in the philosophy propounded by the Englishman Herbert Spencer: that the millionaire was not a conniving brute but a product of natural selection. In Baltzell’s phrase, Spencer served as “a veritable Marx for the millionaires in the Gilded Age.”

Spencer’s protégé, the Yale professor William Graham Sumner (a Skull and Bones man while a Yale undergrad, like several other characters we’ll meet), provided local support for Spencer’s flattering doctrine. Socialist ambitions to feed the poor, said Sumner, would be “nourishing the unfit.” Millionaires, however, were “the naturally selected agents of society.”

Sumner wasn’t a race theorist, however; that was left to the likes of Madison Grant, the product of an old New York line via Yale, a clubman, philanthropist, and author of the 1916 volume The Passing of the Great Race in America. Grant’s book is a taxonomy of the races that finds only “Nordic” sorts capable of civilization. In the introduction to the fourth edition, Grant takes credit for sparking the discussion that led “the Congress of the United States to adopt discriminatory and restrictive measures against the immigration of undesirable races and peoples.” He was terrified of the better sorts being overwhelmed by the lesser, and did not shrink from extreme remedies:

Mistaken regard for what are believed to be divine laws and a sentimental belief in the sanctity of human life tend to prevent both the elimination of defective infants and the sterilization of such adults as are themselves of no value to the community.

The book inspired Hitler, who wrote to Grant saying it was “his bible.”

Nazis put eugenics in a bad light, and the WASPs shed it, at least publicly, but a hierarchical racial imaginary persisted. On one of my visits to the Hamptons in the Seventies, I heard someone say of the area’s Polish potato farmers, who were selling their land to developers: “Their children go to places like Princeton”—he was a Yalie, so this was meant to be patronizing—“and marry white people.”

Eugenics and the rest were strategies for holding on to waning status; the WASPs were hardening into a “caste,” in Baltzell’s analysis, rather than a more fluid upper class, an isolation that would lead to their downfall. (When that happened is a matter of debate, which we’ll sample later.) For Baltzell, the 1920s were the last decade in which the WASPs “had everything more or less their own way.” Given how things ended in 1929, that decade was not a testimony to their stewardship.

WASP power persisted beyond the 1920s, though, as some class renegades joined the New Deal to save capitalism. Roosevelt himself, of course, came out of the upper orders, which is what gave him the confidence to step on their toes, to “welcome their hatred,” as he said in a 1936 speech. Although his popular base was heavily ethnic, urban, and working class, his Cabinet and regulatory agencies were heavy with the pedigreed. It would prove a durable political alliance.

Groton School, June 1940 © Ivan Dmitri/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Among the bastions of WASP power over the decades, along with industry and finance, was foreign policy, which is a polite way of describing the creation and maintenance of a hierarchical world with the United States on the top and the rest of the world sorted beneath. It’s worth taking the measure of the sway the WASPs once held.

Central to that sway was the Council on Foreign Relations (C.F.R.), a group that once had a vital role in the formation of U.S. foreign policy but that now, like many such elite bodies, has some nice real estate and little of its former clout. (As a measure of its slippage, I was invited to a party in the early 2000s to celebrate the relaunch of its website; they distributed mouse pads as souvenirs.) In its official history, written by Peter Grose, the C.F.R. traces its origins to a group of scholars and pundits known as The Inquiry, convened by the young Walter Lippmann, just a few years out of Harvard, who met in upper Manhattan in 1917–18. Its mission was to provide expert advice to policymakers. When President Woodrow Wilson sailed to the Versailles peace conference, he brought with him twenty-three Inquiry scholars. Once there, they met with European diplomats and military men to plot the postwar order. “Plot” is hardly rhetorical overkill. As Grose puts it in that history, Continuing the Inquiry,

In these unrecorded discussions the frontiers of central Europe were redrawn (subject, of course, to their principals’ sanction), vast territories were assigned to one or another jurisdiction, and economic arrangements were devised on seemingly rational principles.

They didn’t want this magical moment to pass. A little delegation of British and American diplomats and scholars decided they wanted a permanent organization to continue the mission of elite geopolitical architecture. When the American branch of this crew returned home, they were intrigued by a group of financiers, businessmen, and lawyers, led by Elihu Root, who’d served as Teddy Roosevelt’s secretary of state, that had convened under the C.F.R. name. Its aim, in Grose’s words, was “to make contact with distinguished foreign visitors under conditions congenial to future commerce.” Their foundational meeting was held at the Metropolitan Club in New York. It was all there, that magic formula of money, elite station, and state power.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that the C.F.R. really began to influence policy. Its members were not happy with the ideas of economic nationalism and self-sufficiency that were floating around during the Depression years, and they set their sights on influencing the Roosevelt Administration—with considerable success. FDR moved away from his initial emphasis on domestic policy as the antidote to the slump and embraced foreign trade as essential to recovery. They were also deeply involved in shaping U.S. postwar strategy—in fact, FDR called them “my postwar advisers.” By 1940, as Kai Bird writes, the C.F.R. was part of an elite consensus that “the United States must soon replace the British Empire as the world’s dominant economic and military power.”

The WASP cohort was central to the design of the post–World War II order and had a strong hand in U.S. foreign policy into the 1970s. They were the progeny of Henry Stimson, known as “Colonel” because of his rank in World War I, though he spent far more time atop the foreign policy establishment as secretary of war under three presidents (Taft, Roosevelt, and Truman) and secretary of state under Hoover. He and Root, his mentor, who’d followed a similar career path a couple of decades earlier, were the prototype of the mid-twentieth-century “Wise Men,” counselors to presidents on foreign affairs and senior managers of the growing American empire.

Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas wrote about six of these counselors in a 1986 book, The Wise Men, which, though it flirts too intimately with hagiography, is still a useful collective biography of the sextet and some of their fellow travelers. Four of them came from the upper orders and were burnished at the usual elite schools: Averell Harriman, son of robber baron E. H.; Robert Lovett, son of E. H.’s right-hand man; Dean Acheson, son of the Episcopal bishop of Connecticut; and Charles “Chip” Bohlen, son of a “gentleman of leisure.” (You can’t gather more than a handful of WASPs without colliding with a “Chip.”) The other two were recruits to the cohort: George Kennan, son of a Milwaukee lawyer, who polished himself up at Princeton, and John McCloy, a poor kid from Philly who earned his Ivy cred at Harvard Law.

As Isaacson and Thomas put it, “They shared a vision of public service as a lofty calling and an aversion to the pressures of partisan politics . . . and an unabashed belief in America’s sacred destiny.” (Years later, Kennan, the nonconformist of the lot, rejected the divine mission talk as “prattle.”) They were, in the words of the seemingly immortal Henry Kissinger, “an aristocracy dedicated to the service of this nation on behalf of principles beyond partisanship.” Translating this high-minded prose into demotic English, they were a group drawn from or admitted to an elite who didn’t think very highly of democracy or the masses.

Nor were they above mixing some business with their lofty moments of public service, particularly McCloy. He worked with J. P. Morgan on a loan to Germany after World War I that served as a private-sector Marshall Plan. After World War II, McCloy became the second president of the year-old World Bank, where he kept away do-gooders and made it safe for Wall Street. He then became proconsul of occupied Germany, where he was complicit in helping Klaus Barbie escape war-crimes prosecution by the French; U.S. intelligence thought Nazis had good information on the Communists and didn’t want to lose them. After that, McCloy became chair of Chase Manhattan Bank, the Ford Foundation, and the Council on Foreign Relations more or less simultaneously. He was also a name partner in Milbank, Tweed, Hadley and McCloy, where he represented the Rockefellers, Chase, and the Seven Sisters, as the global oil giants were known. During this time, he essentially ran U.S. relations with the Middle East. As Isaacson and Thomas put it, “The U.S. government felt it could trust him to look after the national interest as well as the Rockefellers’, and in fact the two seemed perfectly congruent.” It’s no wonder he was named the Chairman of The Establishment in a famous 1962 essay by Richard Rovere, which presented itself as satire but really wasn’t.

The gang was all over the Truman Administration. They drafted some of the documents that would shape the following decades. Kennan, writing anonymously as “X,” published an article in the C.F.R. journal Foreign Affairs that announced the doctrine of “containment”—the need to meet

Soviet pressure against the free institutions of the western world [with] the adroit and vigilant application of counter-force at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points.

That pressure could not “be charmed or talked out of existence.” “Containment” became the watchword for policy during the Truman years. Kennan would later become a critic of the Cold War, and disavow his essay’s unmistakable bellicosity, but he had a huge role in getting the long conflict going.

The right found containment insufficient; it wanted to “roll back” Soviet power. And Truman came to agree. He assembled a group, led by the hawkish Paul Nitze, that included Acheson, Bohlen, and Lovett—to develop a long-term strategy against the U.S.S.R. The document that emerged, NSC-68, called for a massive military buildup, which, though costly, might have the benefit of stimulating the economy enough to pay for itself. Bohlen thought it was too much, but Acheson waved away his objections—and so was born the permanent war economy.

There were boozy Sunday night dinners in D.C., featuring Bohlen, Kennan, CIA bigwig Frank Wisner, Joseph and Stewart Alsop (brothers, insider journalists; both went to Groton; Joe went to Harvard and Stewart went to Yale), Lovett, Harriman, and Acheson. The CIA department of covert ops was set up on Kennan’s suggestion at one of these, and Wisner got the project going. Along with the coups and other dark arts, Wisner ran the CIA’s worldwide propaganda operation, ranging from the popular press to highbrow journals, which he nicknamed his “mighty Wurlitzer.”

Kennan was in many ways the most interesting of the crew, perhaps because of his outsider origins, and became more of a thinker than a doer as he got older. Charmingly, he was pleased his ancestors had been farmers and ministers, and he was proud “they managed to preserve” a middle ground,

between the humiliation of selling one’s labor to others and the moral discomfort of having others in one’s employ—to which I often felt indebted when I grappled with the problems of Marxism.

He wasn’t the only one: Acheson developed an interest in Marx while at Harvard Law School. Bohlen, too, had a youthful flirtation with Marx, even defending the Russian Revolution to skeptical Harvard comrades.

Less charmingly, Kennan harbored some appalling views. “I believe in dictatorship,” he wrote as a young man, during the Depression,

but not the dictatorship of the proletariat. The proletariat, like a well-brought up child, should be seen and not heard. It should be properly clothed and fed and sheltered, but not crowned with a moral halo, and above all not allowed to have anything to do with government.

He thought postwar Germany should be turned into a monarchy. Kennan later turned away from his love for dictatorship, but he never surrendered his contempt for the masses.

That contempt was highly racialized; Kennan had artisanally crafted terms of abuse for every ethnicity and nation humans have ever been divided into, including his own. But he had a clear hierarchy: the best people came from the area around the North Sea. Heading south usually brought trouble. He was not impressed with Italians, but Latin Americans were far worse, and Africans were thoroughly hopeless. He was never caught saying “shithole countries,” but he thought it. Some things are best left unsaid if one cares for reputation.

The gang was largely exiled during the Eisenhower years, as John Foster Dulles, Ike’s secretary of state, dominated foreign policy. Despite some commonalities in background—Princeton, fancy law firm, C.F.R., sparkly club memberships—he lacked polish. His clothing was a mess, his breath stank, and he “stirred whiskey with a thick forefinger,” as Isaacson and Thomas complained.

JFK called the WASPs out of the wilderness and back into positions of power. Although scorned by the snobbish columnist Lucius Beebe as “a rich mick from the Boston lace curtain district,” JFK craved the approval of the old elite, and managed to shed some of that disreputable mickishness at Choate and Harvard. Kennedy brought into the inner circle not only the older generation of savants but new ones as well, notably McGeorge Bundy.

Though his father, originally from Grand Rapids, had clerked for Justice Holmes, Mac’s real pedigree was on his mother’s side: her descent from the Lowells. He sailed through Groton and Yale (yes, a Bonesman too, as were his father and brother, William, a lesser light whom LBJ referred to as “that other Bundy”). From Yale he went to Harvard, where he became a junior fellow in a program established and funded by a great uncle, designed to spare the very special the mundane grind of graduate school.

After serving in World War II (say what you will about these characters, but they didn’t try to evade military service as many contemporary politicians have), Mac ghostwrote Stimson’s memoirs. He moved on to the C.F.R., where he worked on the Marshall Plan, and then joined the faculty of Harvard, where he stayed—lecturing hawkishly and doing some CIA recruiting on the side—until JFK tapped him to be his national security adviser. (Bundy was a hereditary Republican, but that hardly mattered in those days of bipartisan comity.) Bundy was one of the administration’s leading hawks, clinging to the Vietnam War even as it looked increasingly hopeless. His stubbornness led his old friend Kingman Brewster Jr. to say of him, in 1968, “Mac is going to spend the rest of his life trying to justify his mistakes on Vietnam.” Vietnam wasn’t really a “mistake”; it emerged from decades of anticommunism traceable back to X’s essay and NSC-68. The Wise Men’s days of dominating foreign policy ended with the last helicopter out of Saigon. But it must be conceded that they had a pretty good run, designing a relatively stable international order steered from Washington, which endured for decades. There’s little evidence that anyone in foreign policy circles has done that sort of thinking for a long time.

Sons of the Revolution at Delmonico’s, in New York City, 1906, by George R. Lawrence Co. Courtesy Library of Congress.

As the WASPs declined, the topic spawned a mini-genre all its own. Peter Schrag’s 1971 contribution (an early version of which appeared as an essay in the April 1970 issue of this magazine) quotes H. L. Mencken dating the decline to 1924, which Schrag deemed premature (recall that Baltzell had dated the beginning of the decline just five years later, with the stock market crash). Schrag catalogues some of the prominent artists and intellectuals of the time—most were Jewish, a few were immigrants, and some were even black people and American Indians. Foreign Affairs remained soundly Waspish, but gone was the day when “American” meant “WASP” (forgetting enslaved people and their descendants); the native stock had gotten complacent and outnumbered. Sounding like a contemporary celebrant of the internet-driven demise of the cultural and political gatekeepers, Schrag cheered “the vacuum left by the old arbiters of the single standard—Establishment intellectuals, literary critics, English professors, museum directors, and all the rest” as “a sort of cultural prison break.” He did, however, worry that if “the WASP’s mediating function . . . were to be seriously eroded,” chaos could ensue.

Almost two decades later, Robert Christopher’s Crashing the Gates noted all the non-Anglo-Saxons penetrating the corporate elite, some of whom affected the WASP manner—such as Pete Peterson, the private equity mogul who made a second career of trying to eviscerate Social Security and Medicare—and others who didn’t, such as Lee Iacocca, who rescued Chrysler in the 1980s. (Both were sons of immigrant restaurant owners—Peterson of Greeks who owned a diner in Nebraska, Iacocca of Italians who owned a hot dog joint in Pennsylvania.) The gatekeepers didn’t give up without a fight, though. A friend of mine who grew up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, home to the Fords and other old-line auto execs, told me that when Iacocca tried to buy a house in an über-Waspy enclave of the town, it was taken off the market. When he made an offer on another, it, too, was taken off the market. That is caste discipline.

The Decline of the WASP and Crashing the Gates were serious chronicles that largely approved of WASP decline in the name of diversity, but 1991 brought a lament from the right: Richard Brookhiser’s The Way of the WASP: How It Made America, and How It Can Save It . . . So to Speak. (“So to speak” is admittedly a nice touch.) Brookhiser found no virtue in diversification. To him, what came after WASPdom was not a culture but a product of decay. Gone were the days when virtues like conscience, industry, civic-mindedness, and anti-sensuality commanded respect and deference. (Anti-sensuality indeed: comfort is scorned. Thermostats are kept low in the winter, and when I suggested to my WASP mother-in-law that I might get an air conditioner for the room we sleep in at the family summer retreat, I got a look like I’d proposed turning the place into a bordello.) For Brookhiser, part of what killed the old order was modernism—meaning characters like Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche, the instigators of what the French philosopher Paul Ricœur called the hermeneutics of suspicion. In the case of the WASPs, one might suspiciously regard their high-mindedness as a cover for self-interest. But what really did them in, in Brookhiser’s eyes, was not history, not immigration, not their insularity, not massive economic transformations, but a loss of nerve. They got liberal and soft and lost all self-discipline. And that has deprived society of its “immune system” against bad thoughts, bad politics, and bad behavior. If only the WASPs would recover their lost virtues and offer themselves as leaders, “they will be accepted” by a society craving proper leadership.

That seems a stretch, but he has a point about the loss of nerve. In tracing the history of the right’s takeover of the G.O.P., Geoffrey Kabaservice pointed to John Hay Whitney’s shutting down the New York Herald Tribune, a voice of posh, liberal Republicanism, in 1966, because it was losing around $5 million a year (the equivalent of almost $40 million today). Right-wing plutocrats have endured far greater losses to promote their cause: the Rupert Murdoch biographer Michael Wolff estimates that the Rupe has lost over a billion in the nearly four decades he’s owned the New York Post. Kabaservice concludes, “The Tribune’s disappearance was further testimony that moderates were simply less willing than conservatives to suffer and sacrifice for their cause.” Those WASP virtues of discretion and thrift don’t equip you for an ideological war—especially if you don’t think of yourself as having an ideology.

Contrary to Baltzell’s fears that they were hardening into a caste, unable to admit fresh blood, the WASPs encouraged their own supplanting. In the 1960s, the Ivies began opening up to the products of public schools. Under President Kingman Brewster Jr. and the admissions director R. Inslee “Inky” Clark, also a junior, Yale began rejecting legacy WASP applicants in favor of the upwardly mobile. In 1966, the university’s governing body, the Yale Corporation, summoned Clark to explain the sorts he was admitting to the class of 1970. He argued that in a changing America, Jews, minorities, even women might be appropriate Yale material. This didn’t sit well with one corporation member, who pointed to his posh colleagues and said, “You’re talking about Jews and public school graduates as leaders. Look around you at this table. These are America’s leaders. There are no Jews here. There are no public school graduates here.” Inky won that battle, which is why I found myself at Yale five years later—and the same is likely true for Brookhiser, right after me, given his modest origins in suburban Rochester. The transformation of Yale, along with the other Ivies and the prep schools, marked the ceding of power from a hereditary aristocracy to something that likes to think of itself as a meritocracy.

That meritocracy, though more diverse in some senses, is significantly driven by money. The Yale that I knew in the 1970s was shabby-genteel; today’s Yale spends $17 million on a renovation of the president’s house that is described as merely bringing it “up to code.” With their multibillion-dollar endowments, Yale and its Ivy siblings often seem like hedge funds with universities attached. And the student bodies are richer than ever. According to Thomas Piketty,

the average income of the parents of Harvard students is currently about $450,000, which corresponds to the average income of the top 2 percent of the U.S. income hierarchy. Such a finding does not seem entirely compatible with the idea of selection based solely on merit.

As he also says, “parents’ income has become an almost perfect predictor of university access.” Among rich countries, mobility across generations is lowest in the United States and highest in the Nordic social democracies, and this “meritocratic” structure of elite education has something to do with it: since the 1970s, access to higher education has stagnated for children of the poor and soared for the offspring of the affluent. It’s not clear whether the replacement of access via bloodline with access via money amounts to social progress.

Our past few presidents offer a convenient history of the trajectories of class in the United States. George H. W. Bush was the son of a senator, a standard Andover–Yale–Bones WASP of the old school, though clearly not made of the same stuff as Harriman—or even his own wife, it seems, who was described in a 1992 Vanity Fair profile by former associates as “ ‘difficult’ . . . ‘tough as nails’ . . . ‘demanding’ . . . ‘autocratic,’ ” unlike George, who was often thought something of a risible wimp. Bush served only one term, beaten by the upwardly mobile country boy Bill Clinton (with the assistance of Ross Perot, an arriviste yahoo, who presumably drew off a considerable number of Republican votes, a prototype of yahoos to come).

Clinton worked the meritocratic system well, certified at Yale Law, where he met his wife, another product of the meritocracy, though of less disreputable origin. Both of them—it really was a partnership—played a large role in inventing New Democrat politics, shedding all that old New Deal/Great Society stuff in favor of an alliance with business and Wall Street. The political effect of that turn was to consolidate the class victories of the Reagan years by eliminating any serious challenge to the monied from the left. Curiously, that victory led to the partial disintegration of the corporate class. As Lee Drutman shows in The Business of America Is Lobbying, after coming together to promote tax cuts and deregulation in the 1970s, and winning pretty much everything in the 1980s, that broad lobbying effort devolved into pure interest-group politics: tax breaks for me!

Clintonism drew strength from a professional-managerial class that thought itself successful because it was smart. Thinking you earned your status rather than being born into it seems less friendly toward developing a sense of noblesse oblige—but, as the sociologist Rachel Sherman shows in her book Uneasy Street, it also seems to create a class far more anxious about that status than one born into it. That lack of confidence, combined with the lack of deep bonds going back generations, makes for a much less disciplined, less class-conscious elite than the old WASPs.

Clinton was succeeded by a product of the WASP elite, George W. Bush, who ostentatiously rejected it in favor of a Texas persona invented in part with the assistance of Karl Rove, though his father himself did a bit of reinvention with a move to Midland, Texas, in 1951. (Amusingly, G. W. won his second victory against John Kerry, another elite product—it was the first campaign in U.S. history in which both leading candidates were Bonesmen—who, though a veteran and an accomplished athlete, was perceived as a wuss next to the draft-dodging failed college baseball player.) His presidency was a disaster of multiple dimensions, featuring the massively destructive invasion of Iraq and ending in the worst financial crisis in eighty years. Throughout his administration, one wondered where the grown-ups, in the sense of an old-style ruling class, were to rein in the madness—none of it made any sense even on the most orthodox of terms—but there were none.

Those twin disasters of war and economic crisis brought us the presidency of Barack Obama, another product of the meritocracy, though one with more acquaintance with its benefits than Clinton. He went on scholarship to the Punahou School, an elite private academy in Honolulu—not Groton, but not your standard American public school either. From there it was on to Occidental, Columbia, and Harvard Law, a classic meritocratic rise. Fancy institutions treated him well. And far from coming out of nowhere as a presidential candidate, he was recruited to run by Harry Reid after he’d been in the Senate for less than two years (a story told by John Heilemann and Mark Halperin in Game Change that isn’t as widely known as it should be). Reid and other party leaders were worried that a Hillary Clinton nomination would end in electoral disaster—a prescience that was accurate, if ahead of its time. His rise was rapid and charmed.

And although his election was read as a vote for a more peaceful, more egalitarian society, Obama delivered neither. He prosecuted drone warfare with great fervor, which many liberals pardoned because he cited just-war theory to legitimate it. And unlike FDR, he did nothing to create a new governing constituency out of the economic crisis or a new set of institutions that would make the country a better place over the long term. Also unlike FDR, he didn’t welcome the hatred of a discredited elite; it had been good to him, and he craved its further approval. Dodd–Frank and Obamacare don’t hold a candle to the legacy of the New Deal, either in their transformative nature or their power to inspire political loyalty. Under Obama, the Democratic Party lost Congress and state houses at a dazzling pace.

And then came Donald Trump, who quickly made the flimsiness of Obama’s institutional and political legacy very clear. The old George W. question as to the whereabouts of the grown-ups—to hold the lunacy in check—was revived, and their absence was more pungent than ever. Trump undermined many of the institutions created by the Wise Men in the years after World War II, such as NATO and the free trade regime, and it seemed like there was no Establishment to stop him. (Corporate America, which isn’t happy with closing the borders to people, goods, or capital, is not a natural ally for Trump’s nationalism, but since he gave them tax cuts and deregulation, they’ve overlooked their objections.) I’m not lamenting these things: I’m no fan of NATO or free trade. But what’s striking is the system’s lack of defenses to protect its own long-standing interests. Liberals invested a lot of hope in Robert Swan Mueller III—a hockey teammate of John Kerry’s at St. Paul’s—but old Bobby Three Sticks couldn’t put an end to Trump.

What we see in the Trump years are the worst of the old WASP tradition—white supremacy and nativism—with none of the rationality or occasional bouts of noblesse oblige. Like the Wise Men or not, they took the long view. Trump’s vision, if you can call it that, is short-term and backward-looking. Not only is there no hint of stewardship about him and his crowd—they seem to revel in destruction.

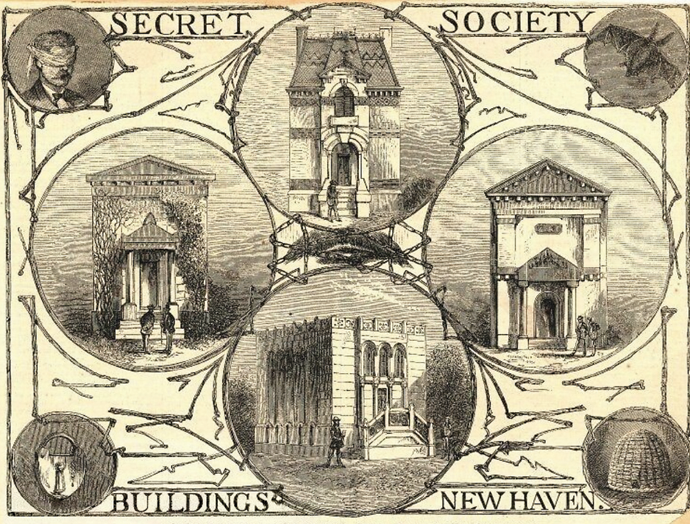

Secret Society Buildings at Yale, circa 1869–1903, by Alice Heighes Donlevy. Courtesy Yale University Manuscripts & Archives.

Those pedigreed geezers of yore alternate among being entertaining, ludicrous, and appalling, but how much does their decline matter to the rest of us? For Baltzell, having an elite of the old sort was a force for stability, setting limits on the possible, even enabling the precisely acceptable amount of dissent:

The radical and confident protest which marked the Victorian era, when many of the most critical intellectuals were reared within a secure establishment, has now given way to the alienated affirmations of deracinated intellectual careerists, all too often supported in bohemian affluence by foundation grants. . . . But unfortunately success is not synonymous with leadership, and affluence without authority breeds alienation . . . the inevitable alienation of the elite in a materialistic world where privilege is divorced from duty, authority is destroyed, and comfort becomes the only prize.

The essential problem of social order, then, depends not on the elimination but the legitimation of social power. For power that is not legitimized tends to be either coercive or manipulative. Freedom, on the other hand, depends not on doing what one wants but on wanting to do what one ought because of one’s faith in long-established authority.

To support his view of the regulating role of an upper class, Baltzell quotes James Baldwin, perhaps a surprising name. As Baldwin said of the old-stock “aristocracies of Virginia and New England” in Nobody Knows My Name:

Their importance was that they kept alive and they bore witness to two elements of a man’s life which are not greatly respected among us now: (1) the social forms, called manners, which prevent us from rubbing too abrasively against one another and (2) the interior life, or the life of the mind.

For those of us who believe in democracy, this is an unsettlingly hierarchical view of society. But in a society like ours, one deliberately structured to magnify elite power and limit the power of the horde—as James Madison said in Federalist 10, the goal was to subdue the “rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project”—the quality of governance depends profoundly on the nature of that elite. So it must be conceded that until the bonds of the Constitution are broken and something approaching a real democracy is instituted, Baltzell and Baldwin have a point. Trump embodies the breakdown of ideological and institutional defense mechanisms and the exposure of a seething political id.

A society like ours—hierarchical in every way, with democracy consciously limited by everything from ballot laws to campaign cash—needs a coherent ruling class, and what we have now is a rabble of plutocrats and grifters. The quality of our governance is brutal and idiotic, and a rotten, money-obsessed elite has a lot to do with that. Trump himself embodies a smash-and-grab ethic, where you load up your businesses with debt, take out the cash, and escape through a bankruptcy filing—the ascension of the business strategy developed in the 1980s by Milken and Rennert to the heights of state power. He’s surrounded by the kind of people who view melting Arctic ice caps as an opportunity to drill for more oil. You might be tempted to think that the old WASPs such as Gifford Pinchot who gave us national parks might be more alert to preventing, or at least adapting to, our evolving climate catastrophe. After all, didn’t George H. W. put an end to acid rain? You might even find yourself nostalgic for a CIA that propagated abstract art and subsidized Partisan Review rather than one run by the likes of Mike Pompeo.

It’s a seductive fantasy that someday the grown-ups will step in and save us from Trump’s Nihilism Express. But they don’t exist, if they ever did, so it’s up to us to perform that rescue. An encouraging thing about the breakdown of the political defense mechanisms is that it provides an opening, not only to Trump’s seething id, but also to challenges from a left unwilling to observe the constraints of Baltzell’s politesse.