Discussed in this essay:

Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright, by Paul Hendrickson. Knopf. 624 pages. $35.

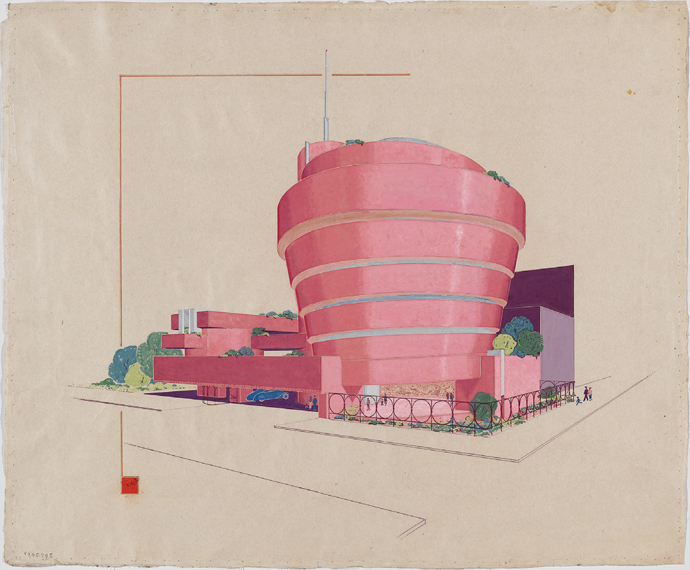

Perspective view of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in pink © The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives/The Museum of Modern Art/Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York City/Artists Rights Society, New York City

Frank Lloyd Wright isn’t just the greatest of all American architects. He has so eclipsed the competition that he can sometimes seem the only one. Who are his potential rivals? Henry Hobson Richardson, that Gilded Age starchitect in monumental stone? Louis Sullivan, lyric poet of the office building and Wright’s own Chicago mentor, best known for his dictum that form follows function? “Yes,” Wright corrected him with typical one-upmanship, “but more important now, form and function are one.” For architects with the misfortune to follow him, Wright is seen as having created the standards by which they are judged. If we know the name Frank Gehry, it’s probably because he designed the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, in 1997. And Gehry’s deconstructed ship of titanium and glass would be unimaginable if Wright hadn’t built his own astonishing Guggenheim Museum on Fifth Avenue some forty years earlier.

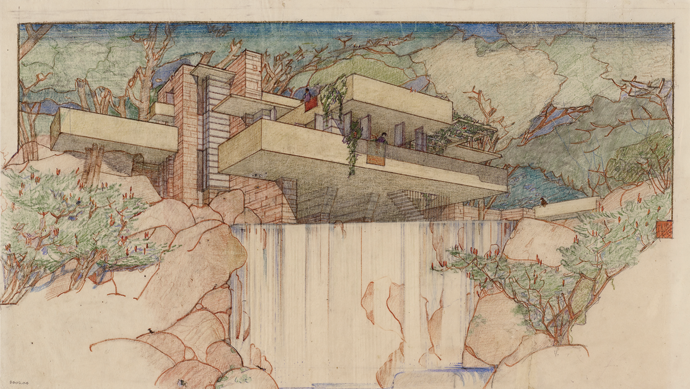

Wright’s inverted ziggurat, still the strangest building in Manhattan, embodies his bedrock principle of “an architecture from within.” He liked to quote Lao Tzu: “The reality of the building does not consist of walls and roof but in the space within to be lived in.” Imagine a spiraling ramp, on which gallerygoers float downward surrounded by art within a white cylinder of concrete. It is a truism that the greatest work of art in the Guggenheim is the museum itself. The same principle of sculpting space rather than erecting walls is at work in the miracle known as Fallingwater. Nestled above a waterfall in the woods of southwestern Pennsylvania, Wright’s suspended dreamscape rises from the natural rock ledges of the rushing stream on hovering concrete slabs of its own. From these extend—like trays on a waiter’s fingers, Wright liked to say—the terraces and jutting eaves of the house. Instead of dominating and domesticating the landscape, Fallingwater adopted Thoreau’s vision of a way to preserve wildness while making an unobtrusive place for human habitation. The architectural historian Ada Louise Huxtable described it as “a rare instance of art not diminishing nature, but enriching it.”

Indeed, Fallingwater barely seems like a building at all, so seamlessly integrated are setting and structure, as though the same forces of nature—rock, trees, water, and sky—had made them both. “Visit to the waterfall in the woods stays with me,” Wright wrote early on in the project, “and a domicile has taken vague shape in my mind to the music of the stream.” Buildings like the Guggenheim and Fallingwater, along with a handful of others in the Wright canon, will doubtless outlast any lingering curiosity about the man himself—a peculiar megalomaniac and the subject of a gothically tinged new book by the biographer Paul Hendrickson. Yet the elusive sources of Wright’s genius are to be found not just in such quiet moments in the woods, but also in the raucous events of his often lurid life.

Long before Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead—and the 1949 film adaptation with Gary Cooper as the Wright-inspired master builder—elevated Wright to a celebrity status rivaling Elvis or Marilyn Monroe, Wright himself, with his Dracula cape and his swept-back silvery hair, had carefully cultivated his own image. He was born Frank Lincoln Wright in a small town in Wisconsin in 1867. His father, William Carey Wright, was a feckless music teacher, composer of languid songs, and itinerant minister who never held a job for long. Wright’s mother, Anna, from the self-important Lloyd Jones family—“pious, maternal, clannish, prideful, Unitarian, Wisconsin-out-of-Wales people,” Hendrickson puts it—thought she deserved better.

When his parents split in 1885—he claimed that his father had deserted the family when in fact his mother kicked him out—Wright adopted a new middle name, the first of many Welsh affectations. Diminutive like his father (five foot seven without his one-and-a-half-inch elevator shoes), Wright longed for the physical and social stature of his maternal uncles. After a drive-by education at the University of Wisconsin, he lied about acquiring various degrees. He bragged that at age seventeen he snuck out of his broken home, made his way to Chicago with seven dollars to his name, and landed a job on the strength of his prodigious drafting skills.

“One of our gold-standard artist-prevaricators,” in Hendrickson’s assessment, Wright had borrowed many of these heroic details from a popular novel by Hamlin Garland. He was actually nineteen when he left home, and drew on Lloyd Jones connections to get his first job, at a time when Chicago, “one of the great building laboratories of the globe,” as Hendrickson calls it, was experiencing a massive construction boom. Wright married a conventional young woman named Catherine Tobin, known as Kitty—sixteen when they met, eighteen at the time of their wedding—in 1889. A year later, he moved into the office next to Louis Sullivan, the greatest of all the Chicago architects, and he supported a growing family that eventually numbered six children.

Moonlighting as a residential architect, Wright designed several arresting houses under assumed names. By 1893, the year of the Chicago World’s Fair—a building orgy known as the White City, in the nostalgic Beaux Arts style—he had opened his own practice, and designed his first acknowledged masterpiece, the William H. Winslow house in River Forest, Illinois. A marvel of symmetry, serenity, and light, the Winslow house can seem, at first glance, a fairly conservative residence, with its overhanging hipped roof and square windows framing the front door. But Wright’s austere design firmly rejected the neoclassical rigidity and ornamentation of the White City. He was coming to believe that a house like the Winslow, with its strong horizontal orientation reinforced by its shallow second story, “should begin on the ground, not in it.” This was to be the great insight of his dazzling Prairie Style, the signature achievement of the first phase of his career.

Wright’s Prairie houses, those heart-stopping horizontal extensions in space, with their cantilevered balconies and terraces, their extensive living rooms, great fireplaces, and recessed lighting, were luxury residences. “By and large they were rich people’s dwellings,” Hendrickson notes, “with their servants’ quarters and spindled stairs and ribbon-glass windows and quarter-sawn-oak astonishments.” The exquisite Frederick C. Robie House, adjacent to the University of Chicago, or the living room of the Frances Little House, preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, make this abundantly clear. Such houses were, in a sense, the logical terminus of certain tendencies in late-Victorian architecture, as it embraced the artisanal (and expensive) Arts and Crafts ethos of John Ruskin and William Morris, casting off excessive ornament and looking for inspiration, instead, in alternative aesthetic traditions such as the clean-edged simplicity of Japanese design.

Japan was of enormous importance to Wright; in a landmark study of 2001, Julia Meech called it “the architect’s other passion.” He was enthralled by the imaginary Japan of the wood-block prints that he treasured and sold on the side, but also by the actual Japan that emerged, after its shocking victory in the Russo-Japanese War, as a nation to be reckoned with. Wright first traveled to Japan, with Kitty, in 1905, just as the war was ending. He eventually developed a sustained rapport with Japanese political and business leaders, winning the lucrative commission for the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. Wright’s design seemed to owe more to Mayan ruins than to specifically Japanese motifs. But just as his design for the Guggenheim would influence all future art museums, Wright’s Imperial Hotel became the model for all future luxury hotels in Tokyo. When the hotel opened, in 1923, it had an immediate stress test in the Great Kanto earthquake, which leveled much of Tokyo. The sturdy Imperial Hotel, however, survived—another chapter in the Frank Lloyd Wright legend.

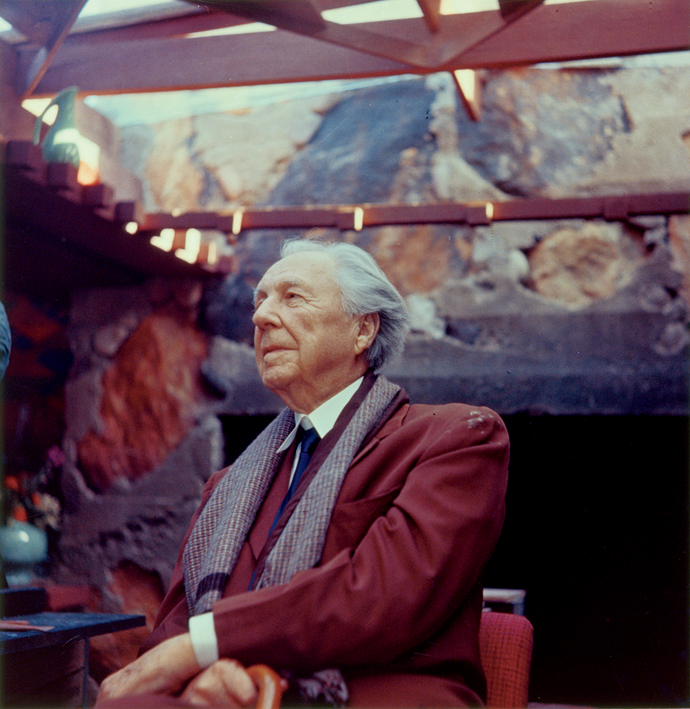

Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West, 1955, by John Amarantides © The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives/The Museum of Modern Art/Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York City

For all Wright’s embarrassing lies, distortions, and embellishments, the Frank Lloyd Wright story isn’t just myth and mirrors. Look at any American building of the past half century, from the lowliest ranch house to the most ambitious modernist wonder, and you can never be quite sure that Wright’s pervasive influence is entirely absent. Wright is said to have invented the carport, that fixture of the low end of American suburbia. He invented radiant heating—which he also called gravity heat and, not a little disturbingly, “holocaust heating”—by burying pipes in concrete slabs, an idea, he said, that came from the submerged sources of heat in Japanese homes. He made innovative use of the corner window and recessed lighting and the open plan, all those interventions that broke up the old box of European architecture, airing it out and streamlining it. “I began to see a building primarily not as a cave,” he said, “but as broad shelter in the open related to vista—vista without and vista within.”

At the more visionary, sci-fi end of the Wright spectrum were all those futuristic fantasies, many of which date from Wright’s shockingly productive final decade—he died in 1959 at the age of ninety-one—when he reinvented himself as a daring modernist. A Greek Orthodox church he designed in Wisconsin, in 1956, looks a lot like a stranded flying saucer equipped with a creepy frieze of eye-like windows. He built a turquoise-tinged office tower in Oklahoma that could be mistaken for a bizarre tree, with concrete floors jutting out like surreal branches. He proposed, outrageously, a mile-high building for Chicago, 528 stories, with floors of various sizes protruding from a central trunk and a trainlike elevator along the side. “It’s feasible,” Wright said with deadpan assurance. “It’s thoroughly scientific. It’s Chicago’s if Chicago wants it.”

In proposing such outlandish projects, Wright loved to play the American upstart, thumbing his nose at the European establishment. He was always declaring independence from English architecture. To his admirers, he seemed to channel the wide-open aesthetics of Walt Whitman (“Unscrew the locks from the doors! Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!”) and Emerson. He introduced into the lines of his houses something of the sublimity of American landscapes: the prairies in his famous Prairie houses, the deserts of Arizona in his second family compound, Taliesin West. After World War II, when the International Style—of Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and the Bauhaus—threatened to colonize America for a second time, Wright played the nationalist card again, even as he skillfully appropriated many of the invaders’ best ideas. By then he was an old hand in making even the most exotic influences—the geometric world of Japanese prints, the stepped patterns of the Aztec and Maya—seem as American as apple pie.

The epic arc of Wright’s building career was matched by epic setbacks, however, as though each triumph called forth an equal and opposite disaster. “I have found that when a scheme develops beyond a normal pitch of excellence the hand of fate strikes it down,” he wrote, with a characteristic mixture of grandiosity and mild regret. “The Japanese,” he said, “made a superstition of the circumstance. Purposely they leave some imperfection somewhere to appease the jealousy of the gods. I neglected the precaution.” Many of Wright’s disasters were self-inflicted. After falling in love with Mamah Borthwick, a freethinking feminist and the wife of a client, he abruptly abandoned Kitty and their six children in 1909. Catastrophe followed, as though in divine retribution.

Plagued by Fire begins with a sustained account of the appalling events of August 15, 1914, which Hendrickson summarizes as follows:

A crazed black servant named Julian Carlton set fire to Wright’s home, Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and went about murdering or fatally wounding seven people, one of whom was the woman Wright deeply loved and had been living with “indecently” for the past several years.

Wright was in Chicago at the time, overseeing a building project; he returned, stunned, to the wreckage, where he quietly played Bach, through his tears, on a surviving Steinway piano.

The tragedy cut Wright’s life in two. Afterward, he took up with an unhinged morphine addict named Maude Miriam Noel—another predictable disaster—whom he eventually married in 1923. Five years later, he married for a third time, more happily, this time to the Montenegrin ballerina and mystic Olgivanna. But the disasters continued unabated. In 1946, Olgivanna’s daughter, whom Wright had adopted, accidentally drove off a bridge, killing herself and drowning her infant son. Taliesin burned two more times. So pervasive were fires in Wright’s life that when his daughter’s bridal veil went up in flames at her wedding, in 1954, he was heard to mutter, “All my life I have been plagued by fire.”

“You would not dare invent Wright’s life,” Ada Louise Huxtable once observed, “it is too melodramatic.” A biographer’s instinct, faced with such Sturm und Drang, might be to tone things down a bit, lower the volume, cut through the melodrama in search of the human contours. Well aware of Wright’s reputation for selfishness and megalomania, Hendrickson does note occasional pockets of humanity: in Wright’s generous treatment of fellow architects fallen on hard times, for example. Two of those architects, Louis Sullivan and Cecil Corwin (an early associate and business partner of Wright’s), were apparently gay, and Hendrickson teases out a possible bisexual tendency—“a capacity for an equivocal something else”—in Wright himself.

For the most part, however, Hendrickson amplifies the melodrama in the Wright story, and wallows in it. “You can’t begin to drill down into Wright’s life without coming face-to-face with a blunt fact,” Hendrickson writes. “So much of his history was attended by the gothic and the tragic, encircled by it, pursued by it. No one has ever quite been able to explain this.” In his own attempt at an explanation, Hendrickson has written less a conventional biography than a gothic tracery, beholden to Poe and Faulkner and the feverish (and repeatedly invoked) prose of James Agee, stitching together what he calls “the dreams and furies” of his subject. Readers interested in a more straightforward treatment might consult Meryle Secrest’s much-admired 1992 biography.

Hendrickson, by contrast, races through the major phases of Wright’s career, dismissing these summarizing sections as mere “connective tissue,” and looping back to events he’s previously covered in detail. This distracting approach, with its “non-linear pockets, or storytelling boxes,” as he puts it, is unfortunate, since Hendrickson, with no expertise in architecture, is particularly skilled in evoking the feel of a building. Describing the labyrinthine entrance to Wright’s wondrous Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois, Hendrickson says it’s “like emerging from the tunnels of an old ballpark and feeling overwhelmed by the sight of the perfect napkin of clipped sunlit green before you.” He adds, “Only it’s as if the ‘diamond’ has somehow been suspended in air.”

Instead of pursuing the central question—surely the only mystery that really counts—of precisely how Wright, the Midwestern hayseed and congenital liar, achieved such enduring miracles, Hendrickson pursues, at obsessive length, mysteries that seem at best peripheral, and perhaps entirely irrelevant, to what the master accomplished. Thirty overwritten pages are devoted to the background of the man who committed the murders at Taliesin, and the possible motivations for the crime. For Hendrickson, the major clue is that Julian Carlton was from a hardscrabble, Klan-ridden town in Alabama, and that his parents may have been born into slavery. There’s a poignant moment when Hendrickson travels to Washington to lay out his scraps of evidence that Carlton’s parents may have handed down their rage at slavery to their son. A genealogist at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture patiently listens to his case. “Maybe your Julian Carlton did come straight up out of slavery,” she tells him. “But in the greater scheme, what does it really matter? Because they were all oppressed people in one way or another from the time they were born.” And what precisely is Hendrickson’s larger point? That the murders were somehow justified, or at least mitigated in their seeming senselessness, by the injustices of slavery?

In an even more extreme speculative foray, Hendrickson manages to persuade himself that the mayhem at Taliesin was somehow behind, seven years later, the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, a vicious pogrom in which whites, seizing on the usual pretext that a white woman had supposedly been assaulted, went on a rampage, killing as many as three hundred African Americans and torching their neighborhood. The tenuous Wright connection, in Hendrickson’s feverish imagination, is a scurrilous newspaper editor named Robert Lloyd Jones, who used his Tulsa paper to whip up white indignation. The editor was Wright’s first cousin. After a lengthy, forty-page account of the horrors of Tulsa, Hendrickson asks, as though anticipating our impatience: “And so you wish to know how any of this long, interrupting, but not-interrupting fable connects directly to the life of Frank Lloyd Wright.” His unpersuasive answer is yet another question: “Is there some awful sense in which 1914 in Wisconsin led inexorably to (or maybe had to be avenged by) Oklahoma in 1921?”

But what exactly is this “awful sense”? Is it that Robert Lloyd Jones, a progressive liberal before he left Wisconsin to take the editor’s job in Tulsa, was converted to KKK bigotry by the murder of his cousin’s mistress by a black man? Isn’t it just as likely that when he came to Tulsa, he took the political pulse of the local population and matched his paper’s opinions to his readers? Extending his gothic theme even further, Hendrickson wonders, in an extended aria, whether Wright’s desertion of his family in 1909 was the real trigger for all the evils that followed:

Is it possible to think that if 1909 had never “happened” (the desertion of your family and the running away with another man’s wife because the two of you in your love and giftedness and freethinking ways consider yourselves above the codes and sanctions that ordinary people try to live by and with), then 1914 might never have “happened,” just as 1921 might never have “happened”?

Again, Hendrickson seeks an expert opinion, trying out his hothouse theory on a Wright scholar.

Whole sections of Plagued by Fire feel cantilevered, one extreme supposition extending out from another. Hendrickson spookily broaches

a proposition that’s never been explored enough: that there are particular F.L.W. houses, for whatever reasons, that seem bent on writing their own versions of his own Byzantine history.

A woman fell or leaped to her death in an elevator shaft of a Frank Lloyd Wright house. A three-year-old boy drowned in a shallow pond near another one. The owner of yet another Wright house, disappointed in love, hanged himself in his family’s basement. Coincidence? Hendrickson doesn’t think so. And yet, are we really to believe that houses designed by Wright come pre-haunted in some mysterious, “House of Usher”–like way, destined for disaster for their doomed occupants? It takes only a moment’s thought to realize that terrible things happen to the owners of many houses.

Perspective view of Fallingwater, the Mr. and Mrs. Edgar J. Kaufmann house, Mill Run, Pennsylvania © The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives/The Museum of Modern Art/Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York City/Artists Rights Society, New York City

Amid all this gothic turmoil, which takes us very far from Wright’s true achievement, one can’t help wondering if there might be a more direct way—more Bach than Wagner—to make some sense of Frank Lloyd Wright’s life and work. One of the best, and least gothic, chapters of Hendrickson’s book is devoted to the masterworks of what he calls the miracle year of 1936. During the previous decade, Wright’s career as an architect had stalled. He had landed no major commercial commissions, and, after walking out on his family, was something of a social pariah in Chicago circles. He was making what money he could by selling his beloved Japanese prints. As the International Style began to win over advanced taste, Wright’s own houses could seem like throwbacks to an earlier, simpler time, redolent of the prairie novels of Willa Cather or the New England nostalgia of Robert Frost.

But in that single year of 1936, in the heart of the Depression and amid his own personal doldrums, Wright conceived three absolutely extraordinary buildings, each of which leaves one with an overwhelming impression of calm and wonder. One was the weightless footprint of Fallingwater, suggesting the possibility of a whole new relation between the built environment and the natural world. A similar ambition for transforming the values communicated by architecture fueled Wright’s design for the administration building of the Johnson Wax Company in Racine, Wisconsin, another masterpiece of 1936. “This new building,” Wright wrote immodestly, “will be simply and sincerely an interpretation of modern business conditions designed to be as inspiring to live in and work in as any cathedral ever was to worship in.”

Curvilinear and streamlined, the extensive redbrick exterior resembles “some Art Deco moon station,” Hendrickson observes. Almost windowless, the low-lying building with its rounded corners turns inward from the surrounding city. Again, this is architecture from within. Inside is the half-acre Great Workroom, a forest of mushrooming columns that, as Hendrickson notes, “widen at the top like plates to hold up the ceiling.” The breathtaking space is illuminated from above by a line of glass tubing—a new technology at the time—conferring a diffuse, ethereal light to the interior. There’s an Alice in Wonderland shift of scale as one takes in the building, as though the columns, in Hendrickson’s comparison, are like giant golf tees.

And then there is the compact Usonian house, another radical experiment in scale of 1936, which Hendrickson believes, with some justification, may be the greatest achievement of all. We often hear today that the age of the starchitect is over; enough with mile-high buildings and the self-important dreams of (mostly male) architects. Eye-catching museums continue to be built to please donors and collectors, but the prizes go increasingly to sustainable buildings and housing for the poor and homeless. Here, too, architects find that Wright, with all his grandiose visions and furies, has preceded them.

Dreamed up amid the deprivation of the Great Depression, the Usonian houses were intended as utopian experiments, houses for the rest of us, democratic residences of exquisite taste and modest price. Wright said he’d borrowed the name from Samuel Butler’s utopian fantasy, Erewhon, but no one else has found it there. The word suggests utopia, unison, and, according to Wright, with a characteristic nationalist touch, the “United States of North America,” with an i inserted for euphony. The houses, some 140 of which are sprinkled around the country, suggest simple solutions rather than grand, operatic gestures. “It’s like being inside a wood-and-brick-and-glass haiku,” Hendrickson writes. Exactly. No basement. No attic. No garage. Expanses of glass that elide the interior with the natural surroundings. And heat emanating up from the floor.

The Usonian houses still look marvelously modern and up to date, a living rebuke to the awful ranch houses and split-level horrors and Dutch colonials that litter our suburbia. “We are living today encrusted with dead things,” Wright told an audience in 1909, when he was about to disrupt his own personal life in search of vitality, “forms from which the soul is gone, and we are devoted to them, trying to get joy out of them, trying to believe them still potent.” Of the Usonian challenge—a challenge not even close to being met amid the social wreckage of 2019, with our woefully inefficient suburbs and our skyrocketing urban rents—Wright remarked: “In our country the chief obstacle to any real solution of the moderate-cost house-problem is the fact that our people do not really know how to live, imagining their idiosyncrasies to be their ‘tastes,’ their prejudices to be their predilections and their ignorance to be the virtue where any beauty of living is concerned.”

Hendrickson calls this, dismissively, Wright’s “hectoring and haughty mode.” Maybe. But Wright had come of age as an architect amid the crushing economic inequality of the Gilded Age, a divide only deepened by the Depression. He knew what he was talking about.

Neither soulless tract housing nor warehousing the poor in anonymous public housing would turn out to be the answer to the problem of affordable housing. Wright’s tiny homes, with their simple building materials, energy efficiency, and exquisite taste, at least suggest an alternative. In pinpointing the challenge as one of fundamental values, of knowing “how to live,” Wright—as so often—was looking in the right direction.