They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears, by Johannes Anyuru. Two Lines Press. 272 pages. $22.95

The Mysterious Affair at Olivetti, by Meryle Secrest. Knopf. 320 pages. $30.

Treasure of the Castilian or Spanish Language, by Janet Hendrickson. New Directions. 64 pages. $11.95

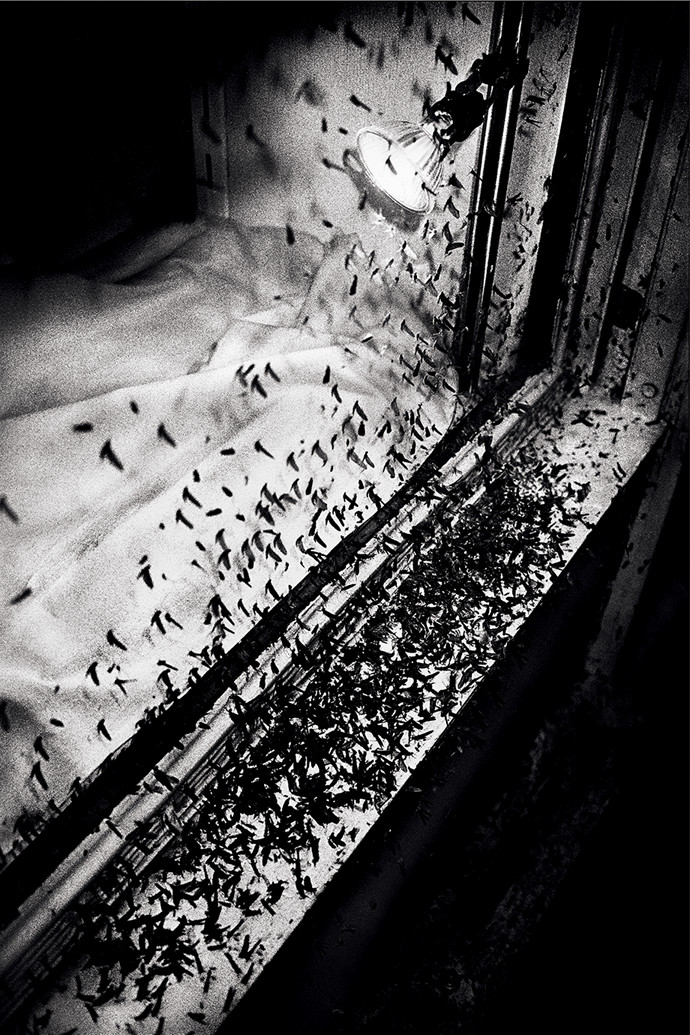

A photograph by Anders Petersen © The artist. Courtesy Pelle Unger Gallery, Stockholm

Questions about the future of Islam in Europe tend to revolve around “Europeans,” reflexively imagined as native-born and white. If reactionary nationalists fear the influence of an “alien” culture, liberals such as Emmanuel Macron fret that “political Islam” is a menace to the secular state. Meanwhile, an estimated twenty-five million Muslims live, work, pray, and wonder about their place in a region tilting right. Among them is the forty-year-old Swedish writer Johannes Anyuru, whose novel THEY WILL DROWN IN THEIR MOTHERS’ TEARS (Two Lines Press, $22.95) is a time-traveling narrative split between present-day Sweden and a parallel-universe future where “enemies” of the nation are consigned to a concentration camp known as the Rabbit Yard. The predominantly Muslim inmates are fed pork, forced to blaspheme by “free speech coaches” and “democracy entrepreneurs,” and tormented by fascist medieval cosplayers called the Crusading Hearts. Some detainees renounce Islam; others die in terrifying neurological experiments.

Anyuru grew up in public housing, the son of a Swedish woman and a Ugandan man who emigrated during the rule of Idi Amin. A former fighter pilot whose credentials were useless in Europe, Anyuru’s father intended for him to pursue a career in civil engineering—an easily transferable skill set should the need arise to flee Sweden. But in high school Anyuru chose to study literature, inspired by an Allen Ginsberg poem about the Vietnam War. He would go on to release three collections of verse before publishing his first novel in 2010. Around the same time, he converted to Islam, describing it as his life’s “great aesthetic event.”

Religion deeply informs Anyuru’s third and latest novel, which draws equal inspiration from quantum theory and Qur’anic hadiths. Artfully translated by Saskia Vogel, it begins with a terrorist attack in contemporary Gothenburg. Events unfold from the perspective of a young woman, one of three jihadists who target a public appearance by a cartoonist famous for obscene cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed. Livestreaming the assault, they take the artist and his audience hostage, preparing to detonate suicide vests once police and press have arrived. The stage is set for a grisly reprisal of the Charlie Hebdo shootings—until the young woman inexplicably thwarts the carnage.

Convinced that she has traveled through time to prevent a genocide instigated by the attack, the woman is incarcerated at Tundra, a psychiatric hospital for the criminally insane. There, she writes to a Muslim journalist whom she thinks is likely to believe her. What follows is an ingeniously plotted work of what could be called theological science fiction. The narrative alternates between two first-person perspectives: the journalist’s account of meeting the woman at Tundra and chapters from the strange manuscript she asks him to read. The manuscript describes her adolescence in a near-future fascist Sweden where she is a teenage social-media adept devoted to a computer-generated pop star. Online, she masquerades as a “regular” Swedish girl—at least until her family refuses to sign a citizenship contract, leading to their internment at the Rabbit Yard.

Common sense tells the journalist that the woman’s story is a fiction. But further investigation reveals that her apparent confusion may be related to a top-secret counterterrorism experiment. It emerges that the woman was once held at a black site in Jordan, where American interrogators connected her brain to an array of quantum computers. They forced her to identify terrorists from attacks in alternate realities, and her memories of life as the girl from the Rabbit Yard may be an artifact of the procedure.

Like Ted Chiang’s story “Anxiety Is the Dizziness of Freedom,” another sci-fi fable about the ethics of prediction, Anyuru’s novel applies the observer effect to a moral quandary. Just as measuring a quantum phenomenon can change it, so too can the effort to predict future violence help usher it into being. This truism of an age when jihadist terror fuels nativist bigotry and preemptive wars swell the ranks of millenarian caliphates is also the structuring irony of Anyuru’s narrative. Did the Gothenburg attack create the Rabbit Yard? Or are both consequences of the experiment in Jordan? For the journalist, the question becomes whether or not to emigrate:

Do I dare stay in this country? I wasn’t just an origin seeking its future on the Western world’s screens. I was carrying shards of another world, different grammar in which I ordered space and time.

Anyuru’s dystopia persuades because it is inextricable from the anxieties of his Muslim characters in contemporary Sweden, from disaffected youths who sell hash and flirt with radicalism to imams preaching forbearance in cramped basement mosques. The grammar of their faith, from its rituals of prayer to its reassurances of eternity, offers a means of orientation beyond precarious circumstances—as well as a counterpoint to the nativist equation of birthplace and belonging. In one of the book’s most moving passages, the journalist visits the grave of his immigrant mother and sadly reflects that she never expected to die abroad. Then, he remembers a hadith: God shapes human beings from the very clay where they are to be buried. “The matter,” Anyuru writes, “was always going to find its way back here.”

Olivetti Lettera 22 poster (detail), 1953, a lithograph by Egidio Bonfante. Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Accessions Committee Fund purchase © Egidio Bonfante Estate/Olivetti SpA

Shaping the future was a more optimistic endeavor for the Olivettis, an Italian corporate dynasty responsible for one of the twentieth century’s most iconic brands. Their business was typewriters, a product they elevated from office appliance to glamorous accessory with the help of renowned designers such as Ettore Sottsass and Marcello Nizzoli. The tocco Olivetti, or “Olivetti touch,” became synonymous with speed, lightness, clean lines, bold colors, and savvy marketing; the company was Apple avant la lettre. Behind its ethos was the humanism of its namesake family, which also found expression in politics, publishing, labor relations, and urban planning. If history had been kinder, their name might have been equally synonymous with the computer revolution.

Meryle Secrest’s The Mysterious Affair at Olivetti (Knopf, $30) is the first English-language history of the legendary Italian firm and a gripping account of its little-known race to develop the world’s first desktop computer. A squat, screenless machine with 240 bytes of memory and a small printer, the Programma 101 debuted in 1965 at the New York World’s Fair, where astonished visitors demanded to see where the “real,” presumably enormous machine was hidden. It sold over forty thousand units, including ten to NASA’s Apollo space program, but a series of tragic accidents forced its creators to withdraw from the field. Secrest contends that the company fell victim to an industrial conspiracy. Equal parts Cold War thriller, family saga, and computer counternarrative, her book chronicles a struggle for control of Italy and the early Information Age.

A veteran biographer of artists and art collectors such as Amedeo Modigliani and Bernard Berenson, Secrest is an engaging guide to the environment that formed the Olivettis, descendants of Spanish Jews who settled in Ivrea, at the foot of the Alps. A freethinking clan affiliated with Socialist intellectuals such as the politician Filippo Turati, they quickly became the town’s largest employers and leading citizens, often sponsoring an annual food fight of medieval origin called the Battle of the Oranges. The family would eventually transform the impoverished peasant comune into a Bauhaus-inspired workers’ paradise. UNESCO recently designated Ivrea “the industrial city of the twentieth century.”

There were many Olivettis, and Secrest’s account of their relationships has the novelistic sensitivity with which Thomas Mann depicts the family firm in Buddenbrooks. The undisputed protagonist is Adriano, a restless visionary who shepherded the company founded by his father to its midcentury zenith. His World War II escapades provide the book’s most inspiring drama: Adriano forged documents for partisan fighters, smuggled fellow Jews and leftists to safety—including the prominent family of his sister-in-law Natalia Ginzburg—and secretly assisted Allied military intelligence, though his starry-eyed communitarianism might have cost him their backing for an anti-Fascist coup. His friend Allen Dulles, the fearsome future director of the CIA, privately sneered at “the charming Utopian Olivetti.”

Olivetti typewriters swept the postwar world. Feted in a 1952 MoMA exhibition as the “leading corporation in the Western world in the field of design,” the company commissioned artists and sculptors to build elegant showrooms everywhere from Venice’s Piazza San Marco to New York’s Fifth Avenue, where Frank O’Hara liked to dash off poems on the sidewalk-accessible Lettera 25. “I’d give up my spaghetti for this here Olivetti,” wrote one wit—and enough people did so that in 1959 the company was able to buy its competitor Underwood in what was then the largest-ever foreign takeover of an American firm.

The company also began manufacturing computers. Forget Steve Jobs’s garage: Olivetti’s technologists worked in a nineteenth-century villa near Pisa, under such secrecy that locals assumed they were building an Italian nuclear bomb. Led by Mario Tchou, the son of a Chinese diplomat, they created Europe’s first fully transistorized mainframe computer, the Elea 9003, named for the ancient philosophic school of Parmenides and Zeno. Next up was the Programma 101, a desktop with the potential to make Ivrea “an Italian Silicon Valley.”

Then, without warning, Olivetti’s keys stuck. In 1960, en route to Connecticut to visit the newly acquired Underwood, Adriano died suddenly. The next year, Mario Tchou perished in a car crash, and in 1964 a market panic and an inexplicable lending freeze forced Olivetti to sell the electronics division to General Electric, which promptly shut it down. The P101 did reach markets, but only because engineers reclassified it as a mechanical calculator to save it from G.E.—a temporary success that did nothing to alter the division’s fate. In a bizarre final twist, thieves stole the prototype, which they surrendered after a police helicopter cornered them in the Alps.

Secrest suggests that the probable author of these “coincidences” was the CIA. In the early 1960s, Italy was on the front lines of the Cold War, and Olivetti was a demi-socialist firm with plans to sell computers to Red China. Through Underwood, it was also poised to compete with I.B.M. America had the means to manipulate markets and kill without a trace. Did Ivrea’s lefty techno-utopians run afoul of Uncle Sam?

Perhaps. But after chapters of suspense, Secrest presents no conclusive evidence of an American plot or even criminal wrongdoing. Her glancing treatment of computer history makes it difficult to understand what about the company’s innovations would have merited such extreme sabotage—including the murder of a longtime CIA ally—especially since the very government that stands accused became a customer. The doubtful conspiracy only slightly diminishes an otherwise riveting biography of the Olivettis and their enlightened enterprise.

Deep in the Sea, by Santi Moix © The artist. Courtesy Kasmin Gallery, New York City, and Matthew Liu Fine Arts, Shanghai

Typewriters are only the most recent casualty of the written word’s progress, following vellum, papyrus, etched stone, and tree bark, among other obsolete items listed under the definition of escribir in an early dictionary by the lexicographer Sebastián de Covarrubias Horozco. “So many have written,” he continues, “that there is no longer room for all the books, nor money to buy them, nor a head that can comprehend all of their titles.” It was 1611.

In Treasure of the Castilian or Spanish Language (New Directions, $11.95), Janet Hendrickson distills a selection from Covarrubias’s fifteen-hundred-page opus into a playful experiment in translation and poetic erasure. Definitions become riddles, anecdotes, opinions, myths, and vintage metaphysical verities. The entry for girasol, or sunflower, simply reads “salute this plant,” while elefante includes the story of one who fell in love with an Egyptian girl also courted by Aristophanes. Elephants, Covarrubias continues, are aroused by mandrake roots and abhor mice “because of the ease with which the mouse can enter the elephant’s trunk and choke it.”

There’s a method to this semiotic madness: Hendrickson’s choices poke fun at the arbitrary nature of definition, etymology, translation, and other word work, undermining the idea that any such activity can ever be objective. There’s always an “I,” and in the Treasure, it’s busy condemning the “insipid” eggplant, regretting the newfangled guitar’s ascendance over the double-stringed vihuela, or asserting that the mustache is the “beard of the upper lip.” There is a selection of personal anecdotes—“I knew of a goat that raised an orphaned boy”—and allusions to the daunting labor of composition, and in the entry for lecho, or bed, the suggestion of a scholarly acquaintance with insomnia.

Hendrickson decided to translate Covarrubias after using the Treasure to look up a word in Lazarillo de Tormes, an anonymous picaresque novella sometimes attributed to his father. The dictionary’s usefulness as a contemporary reference was quickly eclipsed by its “seemingly unregulated beauty.” Her translation is the latest entry in New Directions’ series of poetry pamphlets, which has included contributions by Susan Howe, Osip Mandelstam, Lydia Davis, the cranky ninth-century Chinese poet Li Shangyin, and Eliot Weinberger, to whom Hendrickson offers special thanks in the acknowledgments. Her Treasures, a delightful alchemy of erudite gleanings, has a clear affinity with his own lyric essays.

In Covarrubias’s definitions, words have a liveliness completely alien to modern dictionaries. The fava bean assumes spectral grandeur as “a mournful legume, known to the ghosts of the dead . . . said to breed horrendous dreams.” Alba, dawn, comes down to earth and “walks among the cabbages.” The moon is a “buckler of fire” or “a melon slice,” the coldest part of winter is the yolk of an egg, “insofar as it lies in the middle, surrounded by white.” Sea creatures pursue strange activities. The dolphin, a “marine pig,” enjoys music, while the shark, “a fish that follows ships to the Indies,” eats trash: “upon killing a shark, Cortés and his men found a tin plate, two hoods, and seven gammons of bacon in its gullet.”

Surprising histories lurk in the bellies of sharks and the lives of lexicographers. As Hendrickson tells us, King Philip II once charged Covarrubias with instructing the Moors of Valencia in Catholicism. Spain banned Islam and Judaism in a series of decrees after the Reconquista of 1492, and zealous Christians regularly denounced conversos who refused to eat pork to the Inquisition. The kingdom expelled its entire Moorish population in 1609, as Covarrubias worked on his dictionary. Rejecting contemporary theories that Spanish was “original,” essentially uncorrupted since the Tower of Babel, Covarrubias argued that it bore traces of Latin, Greek, French, Tuscan, Hebrew, and Arabic. Etymology, he recognized, records the wanderings that bring Anyurus to Sweden and Olivettis to Italy, and make of language an elusive and hybrid beast. Like the hare, liebre, a “hermaphroditic” creature with “melancholy meat” that “sleeps with its eyes open.”