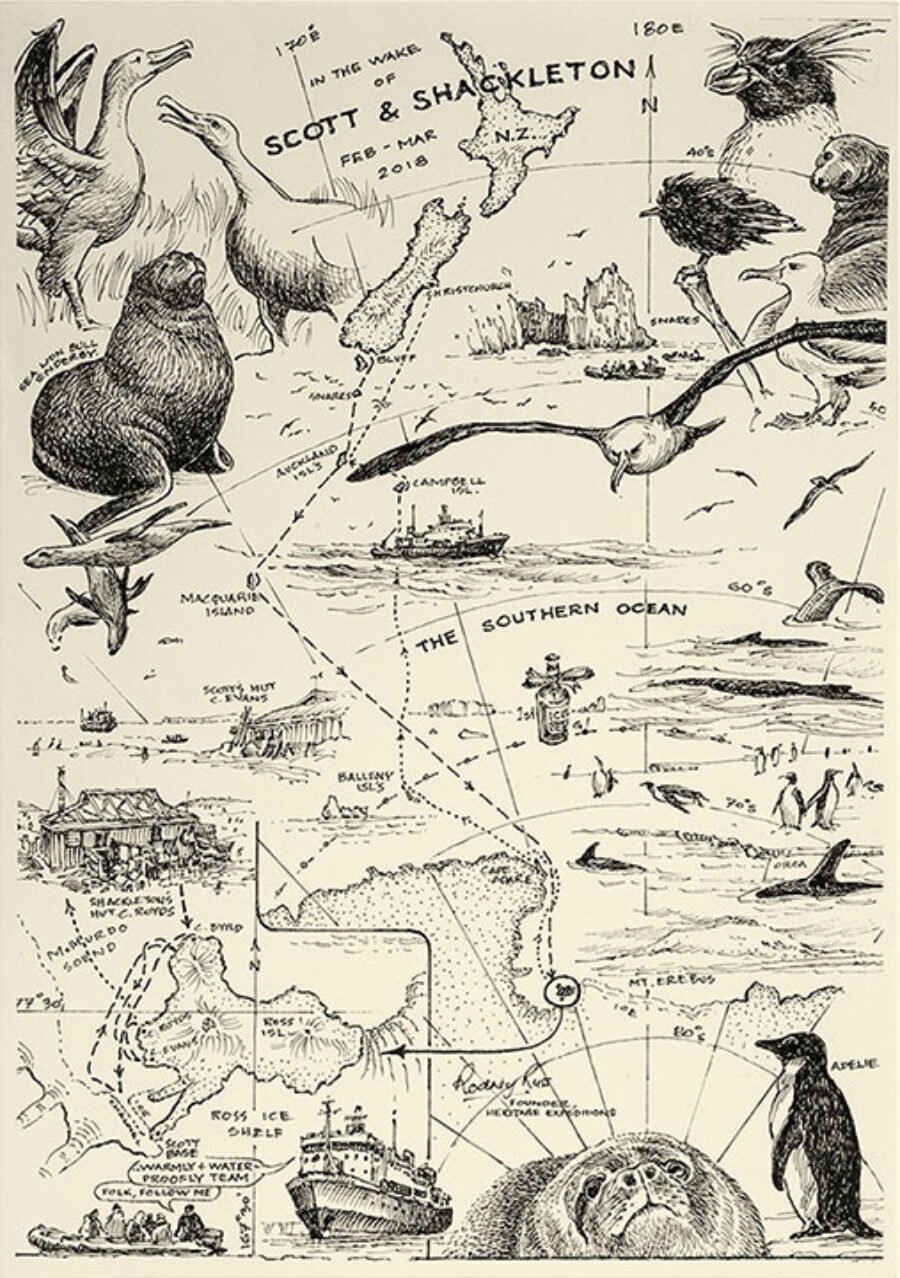

In the Wake of Scott & Shackleton, 2018, a drawing by Peter Anderson, of a voyage inspired by the early-twentieth-century expeditions led by Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton © The artist

Discussed in this essay:

Wild Sea: A History of the Southern Ocean, by Joy McCann. University of Chicago Press. 256 pages. $28.

The Curious Life of Krill: A Conservation Story from the Bottom of the World, by Stephen Nicol. Island Press. 216 pages. $30.

Vanishing Fish: Shifting Baselines and the Future of Global Fisheries, by Daniel Pauly, foreword by Jennifer Jacquet. Greystone Books. 304 pages. $29.95.

If you book a cruise to the Antarctic Peninsula today, you will see ice floes loaded with the expected penguins and seals, situated in a landscape that appears to be a pristine blank. The region seems to erase its own edges from the map, sending up a shroud of mist at the boundaries where the sun-warmed South Seas meet the icy waters of the Southern Ocean, which flows continuously around Antarctica and drives the surprising profusion of life on its shores. Changes to this environment are difficult to discern unless you know its history. For both scientists and historians, discovering what the Antarctic was like before humans altered it means piecing together much fragmentary data, stashed in the archives of many countries.

To the environmental historian Joy McCann, who grew up on the southern coast of Australia, the Southern Ocean is familiar yet “wild and elusive . . . a difficult ocean to pin down.” Her new book, Wild Sea, is a sensitive portrait of a complex ecosystem, from krill to blue whales, and of the ice, winds, and currents that are critical to the circulation of the world’s oceans. Drawing on ships’ logs, captains’ diaries, scientific reports, and correspondence, McCann also gives a meticulous accounting of the effects of human involvement in the Antarctic over the past two hundred years, as scientific research rushed to keep pace with its breathtaking exploitation.

The ecological havoc wrought by sealing, whaling, and fishing in the Southern Ocean hasn’t dispelled the myths of the region as a last frontier of wilderness and limitless marine abundance. But although the Antarctic is even more remote in the mind than it is in distance, the effects of climate change there will be globally felt.

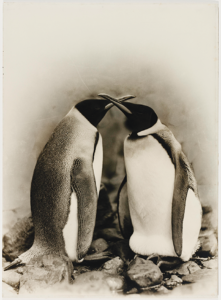

Photograph of king penguins in the Antarctic, by Frank Hurley, circa 1911–14. Courtesy the State Library of New South Wales

Various tribes have made their homes on the Southern Ocean’s northern shores for thousands of years, along the tip of South America, and in New Zealand, where the Maori considered whales their guides between the islands of the South Pacific. But the ocean lay beyond the reach of European sailors until the seventeenth century, when merchants sought new trade routes that forced them into the uncharted waters around the great capes. James Cook was the first European explorer to circumnavigate the Southern Ocean, on a ship called the Endeavour, discovering that its main current flowed clockwise continuously around the pole. His overt mission on his first voyage, in 1768, was to measure the transit of Venus, but it was also an excuse to claim territory for the British crown. The greatest prize was not the islands that Cook encountered in the South Pacific, but the Great Southern Land that philosophers supposed must exist at the South Pole to counterbalance the weight of the other continents. Alexander Dalrymple, the first hydrographer for the British Admiralty, was obsessed with finding Terra Australis Incognita, estimating that it must have fifty million inhabitants.

McCann writes that, “under Cook’s command, the ambitions of science and empire seamlessly converged.” Johann Reinhold Forster, the irascible naturalist on Cook’s second voyage, aboard the Resolution, had departed England with a blessing from Linnaeus that “the eyes and minds of all botanists” were turned toward his findings in the Antarctic. Most of his observations, however, were of the composition of samples of seawater and ice. Eighteen months into the expedition, he counted all the icebergs on the horizon (186). He wrote of the disappointing voyage, “Instead of meeting with any object worthy of our attention after having circumnavigated very near half the globe, we saw nothing, but water, Ice & Sky.”

Sediments frozen in the icebergs suggested the existence of a landmass beyond the ice, but the Resolution did not sail near enough to confirm it. The only lands it encountered on its journey were the remote islands that are distributed like a trail of bread crumbs along the path of the ocean’s current. Turning around at latitude seventy-one degrees south, Cook said of the elusive Southern Land, “I make bold to declare that the world will derive no benefit from it.”

The Southern Land did turn out to be inhabited, though not as Dalrymple had imagined.

Ice Islands, by William Hodges, from Captain Cook’s second voyage. From The Sea Journal: Seafarers’ Sketchbooks. Courtesy the State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

On the Beagle’s second voyage to Tierra del Fuego, in 1832, Charles Darwin was amazed at the variety of life found in the sea off the relatively barren archipelago: snails, starfish, sea spiders, and fish abounded in rafts of seaweed. Several years later, Joseph Hooker, the botanist with James Clark Ross’s Antarctic expedition and a friend of Darwin’s, appreciated the power of an even greater marine forest: diatoms, the microalgae armored in silica that stain the water and ice yellow and brown. “The universal significance of such an invisible vegetation as that of the Antarctic Ocean, is a truly wonderful fact,” he wrote. “The end these plants serve in the great scheme of nature is apparent, on inspecting the stomachs of many sea-animals.” We know today that phytoplankton, kicked up in sea spray, act as aerosols that make that ocean the world’s cloudiest region.

Wild Sea is organized around the various elements of the Southern Ocean: wind, coast, ice, deep, current, and convergence. Each chapter has its delegate species. “Coast” begins on South Georgia’s Salisbury Plain, where McCann is approached by a king penguin:

As I step from boat to beach, an individual separates itself from its companions and waddles up to me. I stand to attention and await inspection. It feels like I am being greeted by a long-lost friend saying “Is it really you?”

This scene is echoed in the accounts of various expeditions encountering Adélie penguins as they forced their ships through the sea ice. Animals in the Antarctic had not yet learned to fear humans, and penguins especially exhibited a social curiosity that captivated explorers, so much that some men admitted to missing the company when they found themselves adrift in empty stretches of sea ice for weeks on end. But McCann notes that most interspecies meet-cutes, however mirthful, ended with the birds’ slaughter, “either to supplement the men’s diet with fresh meat or to be preserved as specimens.” “It seems a terrible desecration to come to this quiet spot only to murder its innocent inhabitants and stain the white snow with blood,” observed the Royal Navy officer Robert Falcon Scott, “but necessities are often hideous.”

Necessity often led to desecration in the extreme environments of the Antarctic, though most instances were justified by profit rather than survival. After Cook reported that Kerguelen Island was crowded with, as his biographer John Cawte Beaglehole writes, “seals whose lack of sophistication made it easy to club them for their oil,” sealing gangs set out to locate other tiny subantarctic isles and skin every fur seal they could find, bringing pelts to luxury markets in New York, London, and Canton. William Smith, who discovered the South Shetland Islands and claimed them for Britain in 1819, said that he had taken sixty thousand pelts. When Henry Forster visited the islands on the Chanticleer a decade later, they were lifeless. As southern fur seal populations declined from between one and two million to fewer than a thousand animals, elephant seals attracted attention with their prodigious blubber, which could be melted down for lighting oil.

Penguins, too, were taken for their oil. McCann recounts a particularly rapacious industry on Macquarie Island, which today is marked by a layer of soil bristling with avian bones. Joseph Hatch, a British pharmacist whose previous ventures were in bone milling and rabbit skins, leased the entire island from the Tasmanian government and boiled three million king and royal penguins in large cylindrical digesters between 1890 and 1920. Hatch, who had been a member of the New Zealand parliament, faced growing public pressure to shut down his penguin-oiling operations. Only after his death was the island declared a bird and seal sanctuary, in 1933, one of the first conservation victories in the Antarctic.

In the nineteenth century, the Southern Ocean became the stage for the revival of the whaling industry, which over four thousand years had depleted whale populations in the Northern Hemisphere. It first established itself in force on the coasts of Tasmania and mainland Australia, where southern right whales went to breed. In 1847, Ross wrote sanguinely of the cetaceans he sighted off the Antarctic coast:

Hitherto, beyond the reach of their persecutors, they have here enjoyed a life of tranquillity and security; but will now, no doubt, be made to contribute to the wealth of our country, in exact proportion to the energy and perseverance of our merchants.

The first explorer to make landfall on Antarctica was Norwegian Carl Anton Larsen, in 1902. His mission was to ascertain the advantage of establishing a commercial whaling base below the Antarctic Circle. He built Grytviken, a factory and settlement, on a South Georgia beach littered with try-pots abandoned by sealers. Larsen’s first financial backer was whaling captain Svend Foyn, an inventor of the grenade-harpoon gun, which had made whaling possible on an industrial scale when it was introduced in the mid-nineteenth century. Blue whales were especially prized, and were larger and faster than the right whale, but were no match for Larsen’s fleets. Other businessmen followed, setting up shop in the South Shetland, South Orkney, and South Sandwich Islands. The unregulated industry left carcasses to rot on the beaches.

Photograph of a blue whale and whalers in Grytviken, South Georgia, by Frank Hurley, circa 1914–17. Courtesy the National Library of Australia, Canberra

Right whales and pregnant females of all species were protected by new regulations in 1914, just as demand for whale oil soared with the onset of World War I. Whale oil greased the war machine. It was used to produce nitroglycerin explosives, and also protected soldiers from trench foot. Between 1915 and 1916, nearly twelve thousand whales were caught off South Georgia, and humpbacks went commercially extinct. McCann describes an emerging pattern:

As one species was hunted to the brink of extinction the whalers turned to another, converging on areas where their prey gathered to breed or feed, then slaughtering and extracting precious oils until the beaches were silent and the waters empty.

In 1925, the British introduced steam-powered factory whaling ships, which could flense a whale and boil its blubber in less than an hour, without needing to return to land. The same year, the British government, fearing for the continued productivity of whale stocks, launched the Discovery Investigations, a series of scientific voyages to study the life cycles, diets, and migration patterns of whales, and to observe firsthand the effects of the industry. Francis Downes Ommanney, a naturalist with the program, reflected on his visit to Grytviken:

What an outcry there would have been long ago, as Sir Alister Hardy has remarked, if herds of great land mammals, say elephant or buffalo, were chased in armored vehicles firing explosive grenades from cannon, and then hauled close at the end of a line and bombarded again until dead.

By 1930, there were forty-one factory ships in the Southern Ocean, taking nearly thirty thousand blue whales in a single season. Within five years, that species, too, was commercially extinct.

Whaling abated during World War II but resumed in force after that conflict’s end. The newly formed United Nations established the International Whaling Commission to conserve what was left of whale stocks, which no longer supplied lighting fuel but rather the essential ingredient in margarine. By the mid-Sixties, however, fin and sei whales were slim pickings in the Antarctic, and the industry inevitably shuttered. An international ban on commercial whaling wasn’t imposed until 1986, in response to pressure from Greenpeace and indigenous activist groups to halt the last holdouts.

By 1959, twelve nations had signed the historic Antarctic Treaty, which set aside the continent for “peaceful” use, protecting its flora and fauna and the access of scientists, as well as specifically prohibiting the testing of nuclear bombs. Fifty-four nations now abide by it. Yet perhaps the only animal wholly protected by the treaty is the continent’s single native insect, a flightless midge that can survive partial freezing—an antipodal analogue of the Arctic’s woolly bear moth. This is because, as Sylvia Earle says wryly in The Last Ocean, a 2012 documentary about the Antarctic biologists who successfully lobbied to make a marine reserve in the Ross Sea, “half a century ago, nations were wise enough to come to an agreement to forestall exploiting the land around Antarctica, and weren’t wise enough to do the same thing for the ocean.” The management of the ocean was left to the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), a body of delegates from the Antarctic Treaty’s member nations. Like the treaty, the success of the CCAMLR has depended on compromise. Its conservation agenda allows for “rational use” of marine resources, a loophole for commercial fishing. This past November, the commission failed for the eighth year in a row to establish a marine preserve in the Weddell Sea.

Krill feeding on phytoplankton in the South Atlantic © Paul Nicklen/National Geographic Creative

A species that doesn’t receive special treatment in McCann’s book is the Antarctic toothfish, more commonly known by its market name, Chilean sea bass. The few species of fish that can thrive in the Southern Ocean are specially equipped: icefish and Antarctic toothfish produce antifreeze in their blood, and icefish are the only vertebrates that lack hemoglobin, absorbing oxygen through their skin. Both species are fished commercially in the Ross Sea. Like the rest of the Southern Ocean’s fauna, the toothfish’s value lay in its crucial adaptation to the cold. Chefs found its flesh—laced with fats that make the toothfish buoyant and able to traverse the water column without a swim bladder—impossible to overcook. It was introduced in 1997 as a delicacy in American supermarkets and upscale restaurants. McCann notes that the baited longlines used to hook toothfish also attract and ensnare albatross and other seabirds (on memorable occasions, they have also hooked colossal squid), though she doesn’t mention its importance in the food web as the prey of orcas and seals, and as a voracious predator in its own right, the largest fish in an ocean without sharks.

But the most important link in the ecosystem of the Southern Ocean—its “fluttering heart,” in McCann’s lovely phrase—is a crustacean, about two and a half inches long, that grazes on algae and swarms like an underwater locust. By some measures, Antarctic krill may be the most abundant living species: 500 million metric tons is a conservative appraisal of the total biomass of the population. Krill swarms in the ocean around Antarctica can extend for miles, and have been observed at three miles deep. They are the linchpin of what biologists call the “wasp waist” ecosystem of the Southern Ocean: many species of phytoplankton convert the sun’s energy into proteins, and many large carnivores rely on a single species, krill, to turn that phytoplankton into a movable feast. A blue whale can eat four tons of krill in a day.

But naturalists in the Antarctic have long pushed against the characterization of krill merely as whale food. Ommanney wrote sensually of their charms in 1938:

The “krill” is a creature of delicate and feathery beauty. . . . It swims with that curiously intent purposefulness peculiar to shrimps, all its feelers alert for a touch, tremulously sensitive, its protruding black eyes set forward like lamps.

The Scottish biologist James Marr, in a monumental 1962 treatise, asserted that krill, “far from remaining a passive drifter, has on the contrary become a creature of great agility, powers of locomotion, purposeful intent, and not a little awareness.”

With his book from 2018, The Curious Life of Krill: A Conservation Story from the Bottom of the World, Stephen Nicol, a krill biologist at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania, continues the work of his forebears with enthusiasm. His life’s research has involved tracking, catching, and counting an evasive quarry. Krill defy easy measurement; in lean seasons they downsize, molting and regrowing smaller exoskeletons, confounding estimates of their age (a krill in captivity named Alan lived as long as eleven years). But knowing how many krill are in the Southern Ocean—and how that number is changing—is vital to understanding the future of the ecosystem.

Photograph of fishermen casting for macroplankton with a dip net, by Frank Hurley. Courtesy the State Library of New South Wales.

The ardor of the Discovery Investigation naturalists had an outcome that some surely did not intend: krill began to tempt the nations that had hunted whales near to extinction. It was reasoned that krill must have become especially plentiful in the absence of their largest predators and were therefore ripe for human exploitation. The Soviet Union led the way with its super trawlers, taking nearly 500,000 metric tons of krill at the peak of its efforts in the 1980s and turning it into krill paste, krill cheese, and krill flakes, feeding it to livestock, and spreading it over their fields. A 1975 article in the New York Times lauded krill as an answer to world hunger, citing an Australian scientist’s calculations that krill “could provide 20 grams of animal protein daily for a billion people.”

Continued optimism over the most abundant source of animal protein in the world notwithstanding, krill have proved difficult to crack. When a krill dies, the powerful enzymes in its belly that dissolve diatoms turn on and swiftly autodigest the body. Catches must be processed immediately to keep the meat fresh. In 1979, krill products were found to contain toothpaste-high quantities of fluoride, a compound that concentrates in krill shells, which further set back attempts to create a palatable krill cuisine. Aquaculture meal and omega-3 supplements are the two commercially viable products that remain. Perhaps because the market for these products increasingly overlaps with consumers who care about environmental sustainability, the major krill-fishing nations today—Norway, Chile, South Korea, and China—have begun over the past few years to limit their operations during the breeding season on the Antarctic Peninsula, where they often compete directly with seals and penguin colonies.

As Nicol notes,

companies continue to fish for krill for a variety of reasons—some political, some because there is a belief that krill will become more valuable in the future, and some just because they want to go krill fishing, and hang the expense.

Much has changed in the Antarctic over the past two hundred years. In the 1950s, a group of Australian biologists toured the subantarctic islands and took note of the species that had rebounded, as well as those that had struggled to return to their former numbers, in some cases over a century after the sealers and whalers had left. The legacy of those sealers and whalers has been continued, unintended, by the stowaways that arrived with their ships. Invasive rodents and the cats introduced to control them have taken a heavy toll on island birds; since cats were eradicated on Marion Island, off South Africa, it has once again been overrun with house mice. During the meager winters, adult albatross, apparently unable to defend themselves, are routinely nibbled to death by bands of mice. Rabbits, left by sealers to breed on Macquarie, have eaten so much grass that they’ve caused landslides onto penguin nests. On South Georgia, Lapland reindeer were introduced to provide sport hunting for the homesick men at Grytviken. After the station closed in 1966, the reindeer grazed unmolested, devastating the island’s native plants, including the tussock grasses in which seabirds nest. Between 2013 and 2014, an eradication team of Norwegian marksmen removed almost seven thousand reindeer from the island and sold the meat to cruise ships.

Nicol tours Grytviken and is astonished by how much remains of the factory in King Edward Cove. Whalebones and harpoons are strewn everywhere, and the corroded boilers, tanks, and cranes remind him of Blake’s “dark Satanic Mills.” Considering not just whales but the repercussions of their absence on the larger ecosystem, he writes,

To the modern visitor to the Antarctic region it is difficult to comprehend how different the Southern Ocean must have looked a hundred years ago. Accounts of the abundance of whales seem almost mythical.

The alleged boom in krill populations, which was supposed to have followed the decline of the whales, has turned out to be largely unsupported. Nicol, whose institute holds the world’s largest trove of whale poop in its freezers, has embraced an alternative theory—that whales fertilize the ocean with iron-rich dung that promotes the growth of diatoms, and in turn the growth of krill.

The krill fishery, worth approximately $69.5 million globally, may be sustainable, but it’s important to consider why krill are harvested at all. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s 2016 assessment, 90 percent of global marine resources were being fished at or beyond their capacity. The historical trajectory of global fishing has been to move southward in pursuit of new stocks as those in northern waters are depleted. The other trend has been to fish down the food chain: after large predators run out, industries move on to their smaller, more plentiful prey.

Océan, by Adolphe Philippe Millot, from Nouveau Larousse illustré, 1898

These shifts can mask the destruction of ecosystems, and are patterns that fisheries biologist Daniel Pauly has been intent on exposing for decades. His newly collected essays, Vanishing Fish: Shifting Baselines and the Future of Global Fisheries, are frank, readable testimony of the shortcomings of fisheries management. Pauly—founder of the Sea Around Us institute and creator of a remarkable online cache of fish information, called FishBase—is best known for his concept of shifting baseline syndrome, an attempt to explain how the world’s fisheries have reached the brink of collapse. Though commercial fisheries in many countries are now required to report detailed catch statistics to regulatory bodies, catch data from before fifty years ago is fragmentary, unreliable, or nonexistent. Even less is known about how populous species were before they began to be fished. Without coherent and continuous historical data, Pauly argues, each successive generation has only its own witness to serve as a reference for future changes. The decline of fish stocks over a lifetime may represent the tip of an iceberg of loss that stretches back hundreds of years.

The greatest current stressors on Antarctic krill are warming seas and the retreat of ice around Antarctica rather than overfishing. Sea ice and the algae that grows on its dimly illuminated underside provide an essential habitat for immature krill. Krill populations in the waters just off the Antarctic Peninsula—the region where sea ice has been decreasing most dramatically—have declined between 70 and 80 percent since the 1970s.

In her closing chapter, Joy McCann asks whether it is possible to cultivate an “ocean consciousness”: “How can we truly know a place that we cannot inhabit?” The question is urgent on many fronts, as the oceans change under the pressures of industrial fishing, plastics accumulation, acidification, and warming. Pauly’s keenest insights into the decline of fisheries come because he acknowledges the relevance of other kinds of records, including historical anecdotes of the kind McCann sifts through. Nicol, too, attests that “science operates by developing stories (we call them conceptual models) about the natural world.” These narratives help us to keep our bearings in the world’s last wild places.