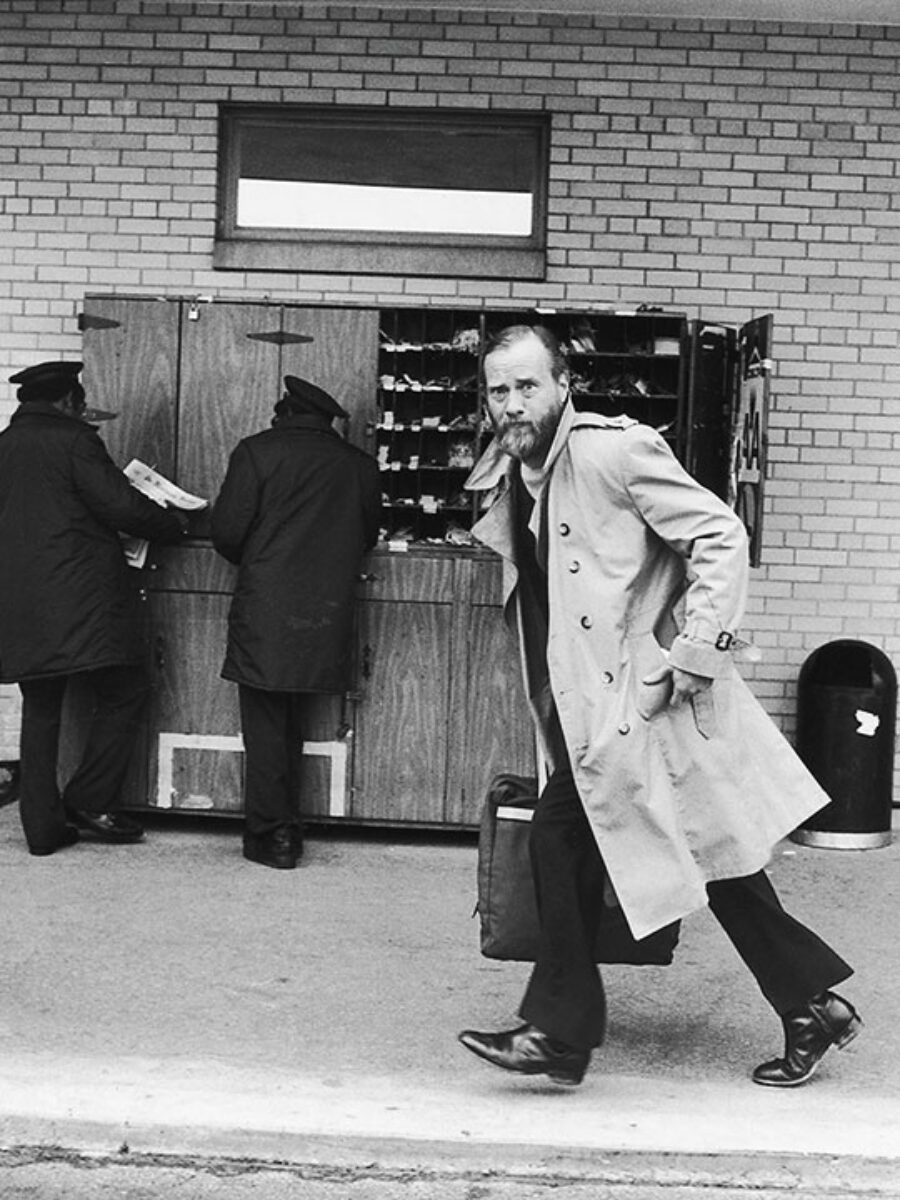

Photograph of Robert Stone © Susan Aimee Weinik/LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images (detail)

Discussed in this essay:

Child of Light, by Madison Smartt Bell. Doubleday. 608 pages. $35.

Robert Stone: Dog Soldiers, A Flag for Sunrise, Outerbridge Reach, by Robert Stone, edited by Madison Smartt Bell. Library of America. 1,216 pages. $45.

The novelist Robert Stone once said that his subject was “America and Americans.” Indeed, as Madison Smartt Bell writes in his new biography of Stone, Child of Light, Stone’s fiction depicts “the evolution of America’s sense of itself—from the naïve ebullience of the 1950s to the tenebrous uncertainties of the post-9/11 twenty-first century,” and it did so in a way that was “always just a little ahead of the curve.”

That almost prophetic quality is perhaps most evident in his first novel, A Hall of Mirrors (1967), a depiction, eerily familiar in our own era, of the far right’s use of mass media to exploit Americans’ racist fears. The book follows a failed clarinetist named Rheinhardt as he goes to work as a Limbaugh-ish political commentator at a New Orleans radio station, WUSA. His boss, Bingamon, a businessman—large, tanned, and seemingly ageless—advises his new employee that the task of radio will now be, and should be, the speaking aloud of the unspeakable. Breaking through barriers of propriety is the way to success. To get an audience, Bingamon asserts, you first have to give voice to the audience’s prejudices and its lowest fears and angers. “Because there is a pattern,” Bingamon tells Rheinhardt.

They feel it, they pick up a trace of it here and there. . . . People can’t see because they don’t have the orientation, isn’t that right? And a lot of what we’re trying to do is to give them that orientation.

After A Hall of Mirrors and its mordant portrait of American racial anxieties, Stone’s subjects ranged widely. Next came Dog Soldiers (1974), one of the great Vietnam novels, centered on a drug deal gone awry. With A Flag for Sunrise (1981), Stone turned to American adventurism in Central America, and from there, in Children of Light (1986), to the story of a schizophrenic actress in cocaine-addled 1980s Hollywood. Damascus Gate (1998) focused on America’s relations to the Middle East, and particularly Israel. His final novel, Death of the Black-Haired Girl (2013), was a campus thriller.

In a world ruled by dramatic ironies observed by athletes of perception, to use one of Stone’s key phrases, the agents of goodness and mercy are few, and nature is no help at all. His protagonists tend to be wild, intelligent charmers in the grip of a singular preoccupation. His novels take the form of hallucinatory realism, the typical narrative invariably starting in the real world but usually traveling to Stone’s particular version of Oz, where things are not what they seem and, to quote a character from A Hall of Mirrors, “Something fucking awful is happening all the time.” Intricately plotted and often suspenseful, his fiction tends to run a low-grade fever generated by ambition, racism, fear, drugs, and alcohol, conveyed in a tone that has the odd property of being both frightening and disconcertingly funny. In this particular mode, Stone was unsurpassed, and at least two of his novels, A Flag for Sunrise and Outerbridge Reach (1992), about an amateur sailor who enters a solo race around the world, have a political scope, eloquence, and cultural knowingness that qualifies them as great novels.

Mania rules in many American classics. Like it or not, in what has been taken to be our national literature, the notable white male characters are often in the grip of obsession. From Captain Ahab, to Frank Norris’s McTeague, Fitzgerald’s Gatsby, Faulkner’s Thomas Sutpen, Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert, Philip Roth’s Portnoy, and James McBride’s John Brown, we are in the presence of men who want only one thing and have sold their souls to get it. These people are outcasts of one sort or another. They can be polite, but polite society is nothing to them. They are visionaries in the best and worst ways, and when they self-destruct, as they usually do, they take others with them.

Given this set of conditions, the truest literary ancestor of Robert Stone may be Nathanael West, whose novel The Day of the Locust (1939) concludes with a riot that may have been the model for the violent Trumpian rally at the end of A Hall of Mirrors. Here is West’s description of the rioting crowd:

They were savage and bitter, especially the middle-aged and the old, and had been made so by boredom and disappointment. All their lives they had slaved at some kind of dull, heavy labor, behind desks and counters, in the fields and at tedious machines of all sorts, saving their pennies and dreaming of the leisure that would be theirs. . . . Where else should they go but California, the land of sunshine and oranges? . . . They get tired of oranges. . . . They watch the waves come in at Venice. There wasn’t any ocean where most of them came from, but after you’ve seen one wave, you’ve seen them all. . . . [Newspapers and movies] fed them on lynchings, murder, sex crimes, explosions, wrecks, love nests, fires, miracles, revolutions, wars. . . . The sun is a joke. Oranges can’t titillate their jaded palates. . . . They have been cheated and betrayed. They have slaved and saved for nothing.

West and Stone both employ a form of lyrical, sour wit that is omnipresent but often just below the radar: you can feel it working its way through the plot like a demonic influence, but you can’t quite pinpoint its origin. As Bell writes, contrasting Stone with Norman Mailer, Stone was “an artist of extreme indirection.”

Where Mailer liked to butt into the big issues of his time head-on, Stone was more inclined to ambush them. Stone’s work included a take on most of the seismic social changes of his time, but as an artist he was less interested in political and cultural events per se than in the movements of chthonic forces underlying them.

Stone’s fiction is not uplifting and cheerful, nor does it make you feel better about yourself. It offers, instead, narratives of disillusion, in which we discover what we really are.

Bell knew and obviously loved Robert Stone. His lengthy and detailed biography, whose publication arrives at the same time as the reissue of three of Stone’s novels in a Library of America edition, views its subject with an offhand, tolerant affection. Stone is called “Bob” all the way through, liquor is often referred to as “grog,” and very little critical distance exists between the biographer and his subject.

This devotion softens, slightly, the harrowing narrative of Stone’s early life. If misfortune constitutes a writer’s gift from the gods, Stone was remarkably blessed. An only child, born in Brooklyn in 1937 to a schizophrenic or bipolar mother and an absent father (“I really don’t know who he was,” Stone once said), he lived with his mother in a succession of single-room-occupancy hotels and shelters around New York. After fleeing to Chicago and then returning to New York, they briefly lived on the rooftop of an apartment building on Lexington Avenue. During some of this time, Stone was enrolled in a Catholic school run by the Marist brothers, St. Ann’s Academy, which he later described, in a story, as having “the social dynamic of a coral reef.”

“Everybody was very unhappy there,” Stone remembered. “[The Marist brothers] certainly slapped people around right and left.” His sense of oppression never quite left him, nor did the compulsion to find an escape hatch. Along the way, he learned Latin, a gift that stayed with him as an adult, and he read poetry in Latin for pleasure. The other details of Stone’s upbringing are dispiriting: in adolescence, he repeatedly showed up to school drunk, joined a New York street gang, and was expelled in the middle of his senior year. At the age of seventeen, he joined the Navy.

Stone found the Navy a step up in civility, despite his experience of fighting off a rape aboard ship by using a chain to defend himself. In 1956, having been sent to Port Said on the U.S.S. Chilton at the outbreak of the Suez Crisis, Stone saw the corpses of Egyptians killed by French bombers floating in the water. The sight seems to have been a turning point of sorts. Years later, he described his response to it: “I always thought that the world was filled with evil spirits, that people’s minds teemed with depravity and craziness and weirdness and murderousness, that that basically was an implicit condition, an incurable condition of mankind.” That same night in Egypt, he recalled, he had this insight: “This is the way it is. There is no cure for this. There is only one thing you can do with this. You can transcend it. You can take it and make it art.”

Stone’s lifelong challenge was to find ways of slipping the wildest and most frenzied visions into what seemed like plausible narratives, and his greatness as a writer is a reflection of how often he succeeded. Near the end of Stone’s Outerbridge Reach, for example, the book’s protagonist, Owen Browne, is stranded on an “icy stone island” in the Southern Hemisphere after his shoddily made boat falls to pieces during the race. By now “in the grip of something powerful and unsound,” he enters an abandoned house and feels something “trying to direct his attention toward the window.” The sentences that follow shimmer with exactitude and madness.

Finally, broken-willed, he consented to turn, dreading the thing that might confront him in the window. There, in place of the declining sun, he saw innumerable misshapen discs stretched in limitless perspective to an expanded horizon. It was a parody of the honest mariner’s sighting. Each warped ball was the reflection of another in an index glass, each one hung suspended, half-submerged in a frozen sea. They extended forever, to infinity, in a universe of infinite singularities. In the ocean they suggested, there could be no measure and no reason. There could be neither direction nor horizon. It was an ocean without a morning, without sanity or light.

By the time Bell’s biography reaches the tragedy at Port Said, we are only thirty-two pages into a six-hundred-page work. Stone soon gets out of the Navy (“I actually had a pretty good time in the Navy,” he later said), tries journalism, gets married, goes to New Orleans, sells encyclopedias, and witnesses overt Southern racism up close. He works as a census taker, and gives jazz-poetry readings. (“Sometimes,” he recalled of those readings, “after Tulane football games, the players would come in and throw bananas at us. This cost them nothing, since the bananas, in bunches off the dock, were hung from the ceiling and the bar pillars.”) By 1962, he and his wife have moved to San Francisco, where he falls in with Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters and spends some time traveling with them and getting high and noting what hallucinogens do to the psyche—in one case, causing him to see physical manifestations of the notes Coltrane played during a concert, unaware meanwhile that he had stepped on a nail. (“When I took my shoe off it seemed that my sock was drenched in blood—bright blood, the color of John Coltrane’s soprano sax riffs.”)

He also has a stroke of luck: the woman he married, Janice Burr, was a loving and loyal companion, and mother to two of his children. Early on, she recognized that for him, “drinking was already a necessity,” and she emerges in this biography as a support to him throughout his life. The story of Robert Stone’s career is consequently, at least in large part, about their marriage, as well as, with his increasing stature following the success of Dog Soldiers and A Flag for Sunrise, the attendant book tours, the teaching, the screenwriting, the awards, the friendships, and—perhaps most of all—the substance abuse.

No one can smoke, drink “heroically” (Bell’s word for it), and do drugs with any regularity without some unwholesome systemic results, and the last third of this biography tells the inevitable story of Stone’s physical decline. It is not an account for the faint of heart. What’s remarkable is that despite his afflictions, Stone was still able to do so much good work before his death in 2015. At the time of the completion of Bay of Souls, in 2003, Bell observes, Stone had “been to hell” and “had come to the edge of losing absolutely everything—not just Janice and his marriage but his very life and breath.”

Stone’s struggle with alcohol informed much of his writing. In A Hall of Mirrors, once Rheinhardt accepts the job at the conservative radio station, the boss, Bingamon, seals the deal by offering Rheinhardt a glass of Southern Comfort, which he reluctantly drinks. What follows is a paragraph that only an alcoholic could write, and it fuses power, vision, and the demonic.

When it was down he knew it had been a mistake. After the first warm relaxation he felt the sudden careening of his brain, the dives; standing a foot from Bingamon with the glass in his hand, the foolish smile still on his face, he was plunging headlong into the dives, the whirling breathless curves that led, always to the lights—he could see them down at the bottom, flashing yellow and red. He had to get out now, he told himself. He had to get out.

That’s what a devil’s bargain looks like, and there’s no escape; you don’t get out of it.

Few other American writers of his period, with the notable exception of Denis Johnson, seem to have believed in demons as firmly as did Stone. At the beginning of Dog Soldiers, a journalist named John Converse finds himself on a bench in Vietnam with a middle-aged woman, a missionary. She tells him that up north in Ngoc Linh they worship Satan. When Converse informs her that, like most people, he doesn’t believe in Satan, because it’s too “spooky,” the woman replies, “People are in for an unpleasant surprise.”

The English novelist Wyndham Lewis wrote in his novel Self Condemned (1954) that, “like all good Americans they”—his British characters—“came to realize that it was only the comic that mattered,” and if Stone’s work is notable for its darkness, that darkness also served him as a resource for wild laughter. Consider, in A Flag for Sunrise, the protagonist Holliwell’s drunken speech to an angry university audience in a fictional Central American nation: “ ‘In my country we have a saying—Mickey Mouse will see you dead.’ There was silence. ‘There isn’t really such a saying,’ Holliwell admitted.”

In 2010, I found myself dining alone in a little northern Minnesota restaurant and had brought along Stone’s second collection of stories, Fun with Problems (2010), for company. He was a wonderful short-story writer, and his story “Helping” has been widely anthologized. While waiting for my fish sandwich, I began reading the volume’s fourth story, “The Wine-Dark Sea,” and came to a passage in which a character named Eric, “a few weeks out of rehab” and driven by wine and what the narrative calls the “spell of his demon,” begins to expound to his friends the truth behind appearances. In the attack on the World Trade Center, he claims, there were no actual planes. We were all fooled and deluded by “fractal imaging.” Inspired and lifted up, Eric begins to sound like someone on midnight AM radio or like the shabby stranger who sits down next to you in the waiting room for an enlightening chat.

“You guys heard about history being mere fiction. That’s the way it’s always been. Heard of the Romans?” Eric demanded. “They never existed!” He raised his voice. “It’s baloney. I mean, there’s Rome, right. But there never were any Romans with togas and shit, and helmets and feathers. A fairy tale out of the Vatican Library. They even dreamed up the idea of a Vatican Library. There isn’t one! . . . The Greeks! There weren’t any Greeks, not ever. I know there are Greeks, but they’re not the Greeks. I’ve been to so-called Greece. Plato? Mickey Mouse’s dog. Babylonians. Israelites? The pyramids are like forty, fifty years old . . . This shit is all made up by the government. Once more unto the breach, dear friends—what a laugh. You think people in iron suits rode around on horses? Horse shit is more like it. Don’t give up the ship? I mean—come on!”

On page seventy-six of my copy, a brown stain marks where I started laughing so hard that I spat out my coffee, to the consternation of my waitress.

The only other time I can remember laughing that hard at a passage in a book was when I read Stone’s memoir of the Sixties, Prime Green. I had reached chapter eleven, an account of Stone’s period of employment at a cheap tabloid, which he calls National Thunder. One of his jobs was to come up with outrageous headlines, and his triumph was “Sky-Diver Devoured by Starving Birds.” Stone was so proud of that headline that much later he wanted to use it as a title for a book.

One finishes Bell’s biography, which could almost have been titled Darkness and Laughter, with a renewed respect for its subject and a feeling of awe for the love he inspired in his biographer, wife, children, and friends. Writing in an essay about Malcolm Lowry, author of Under the Volcano and also an alcoholic, Stone observed,

In Under the Volcano Lowry used the grim experiences he had gone through to express his love for the world. He applied his considerable learning and generosity of spirit to a hundred things beyond his own despair, even if the experience of despair informs it.

“So we pardon Lowry his unhappy life,” Stone goes on. “The alcohol was bad luck.”