From This Brilliant Darkness, out last month from W. W. Norton. The book is composed of short essays about encounters Sharlet had while photographing strangers.

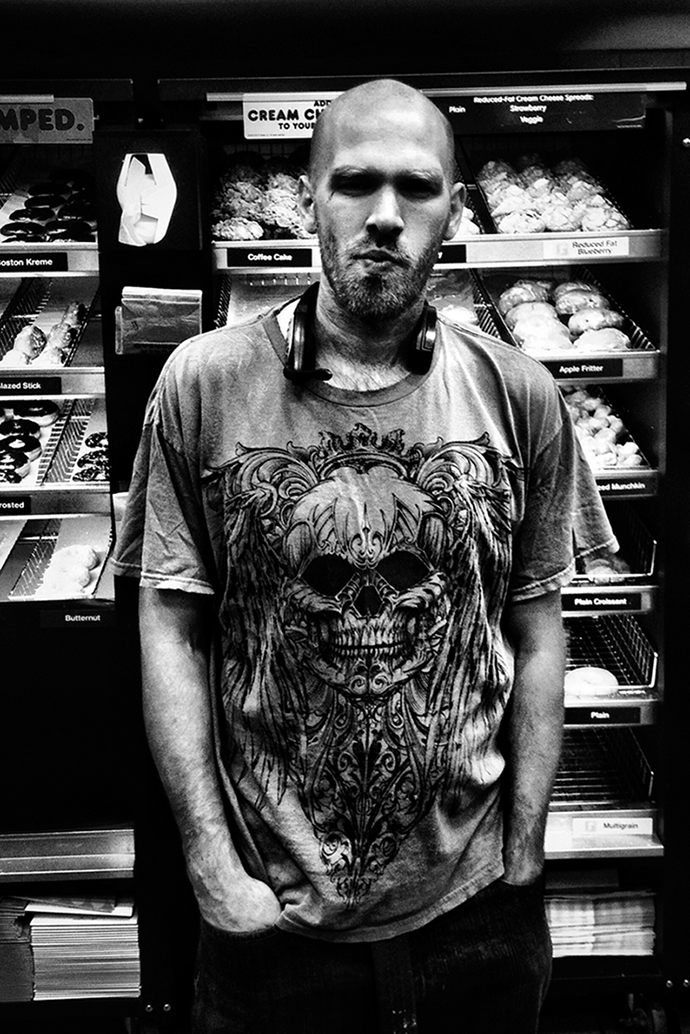

mike

All photos by Jeff Sharlet

The night shift is for me a luxury, the freedom to indulge my insomnia by writing at a Dunkin’ Donuts, one of the only places open at midnight where I live, up north on the river between Vermont and New Hampshire. Lately, though, my insomnia doesn’t feel like such a gift. Too much to think about. So click, click goes the camera—the phone—looking for other people’s stories to fill the hours. This is Mike; he’s thirty-four, he’s been a night baker for a year, and tonight’s his last shift. Come 6 am, “no more uniform.” He’s says he’s going to be a painter. What kind? “Well, I’m painting a church . . . ” He means the walls. The new job started early, too. “So I’m working, like, eighty-hour days.” He means weeks. He’s tired. He doesn’t like baking. Rotten pay, rotten hours, rotten work. “You don’t think. It’s just repetition.” Painting, you pay attention. “You can’t be afraid up there.” The ladder, up high. “I’m not afraid,” he says. “I can do anything.” He says he could be a carpenter. “But it hasn’t happened.” Why does he bake? “Couldn’t get a job.” Work’s like that, he says—there are bad times. Everything’s like that, he says. There are bad times.

“Who’s the tear for?” The tattoo by his right eye.

“For my son,” he says, “who died when he was two months old.”

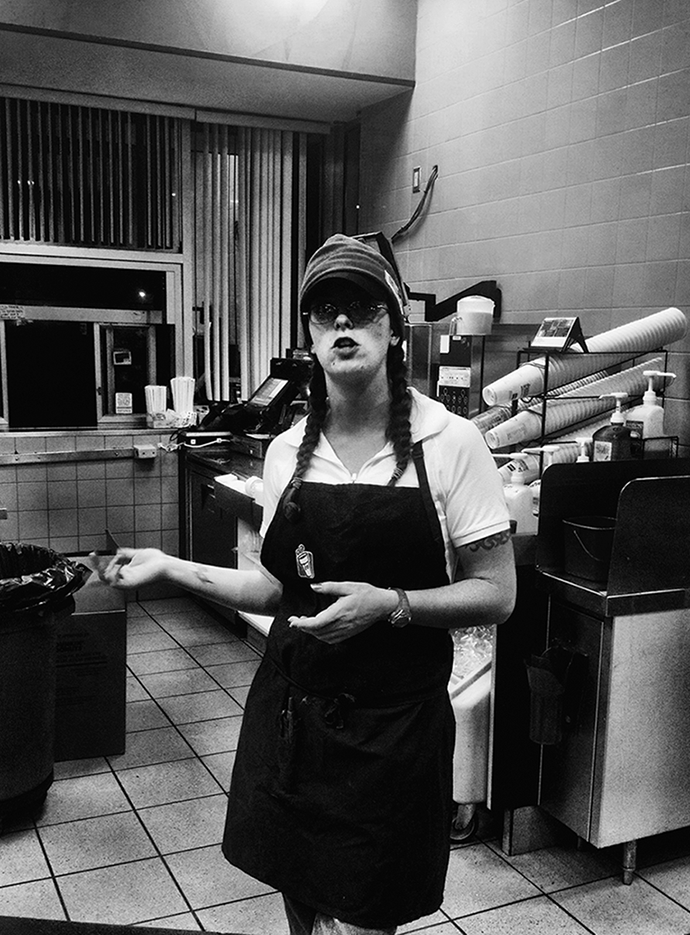

kelly

Kelly’s twenty-seven. She started baking doughnuts when she was seven. “My mother was the night baker before me,” she says. “If I was, you know, ’naughty,’ she took me with her.”

Kelly followed that routine for years. She quit. She returned. She’s been working here a year and a half, a night baker like her mother.

She takes her smoke breaks out front, because there’s no camera out back. “We’ve been robbed,” she says. A man walked in the back door, emptied the safe. Kelly wasn’t working. “I’m just lucky,” she says.

She’s quitting again in two weeks. She’s going to be a security guard, night shift. “Fifteen dollars an hour.” The sum makes her marvel. She won’t mind the hours. She doesn’t like days.

“The night shift,” she says, “I’m wired for it.” She’s a natural. But she’ll back, she says. For coffee. “I don’t eat doughnuts anymore.”

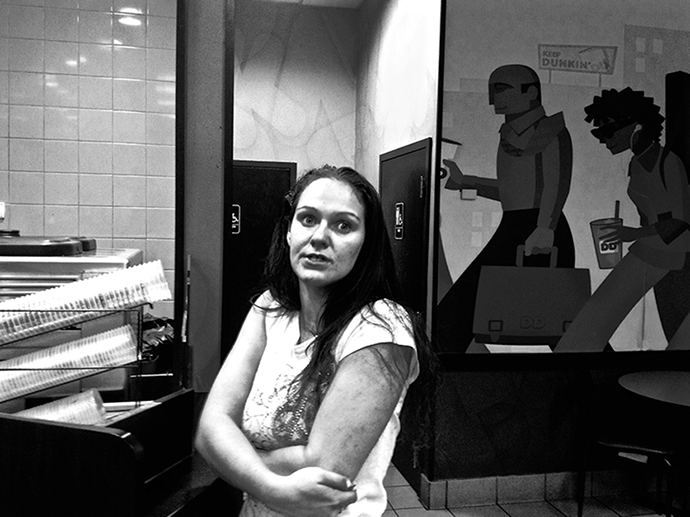

the nurse

Night nurse for thirteen years and that was enough, at least for a while. She was good with difficult children. The troubled ones, the violent ones: she knew how to calm them. Night nurse thirteen years; she couldn’t take it anymore. “But I’ll go back,” she says. “This is just for a little while.”

She and her wife used to live in the city. Manchester, New Hampshire. “It’s a tough town,” she says. “We didn’t want to do it anymore.” They decided to move to the country, roughly speaking; they have an apartment near the highway and the hospital. “What changed was my daughter,” she says. “My daughter is three years old. I didn’t want her growing up around that.” Manchester, New Hampshire. “It can be a very tough town.”

Night shift at Dunkin’ Donuts, a few months now. “I shouldn’t be here,” she says. But she is. “My daughter will be safer.”

peri

Peri likes her curves. When she visits Dunkin’ Donuts, she finds she needs to do a lot of stretching. Lean, arch, twist. She smiles; she flirts a little with Mike behind the counter. I wanted to take a picture of her pretty like that, happy. 1:15 am.

She’s the night manager at the Taco Bell next door. She trades Taco Bell for Dunkin’, quesadillas for coffee, two or three cups a shift. She used to manage a Wendy’s down in Dover, New Hampshire. “I’m a city girl,” she says. Concord, then New Jersey, then Dover, then here, which is the least like a city of all.

She was at Wendy’s for eight years. One night, smoke break, Peri got robbed. “2:38 am,” she says. She wraps herself in her arms. A man with a gun and zip ties. He said there were more men waiting. Peri screamed. He took $3,000. He took somebody’s truck. Peri waited for him to be gone. “I could smoke,” she says. Hands zip-tied together, she’d held on to her cigarette. That’s what she remembers. And: “I thought about my daughter.” One year old. Peri couldn’t take chances anymore. That night, zip-tied, she decided to move. That’s how she came here. She says they caught the stickup man. “He said he did it for his family.” She doesn’t believe him.