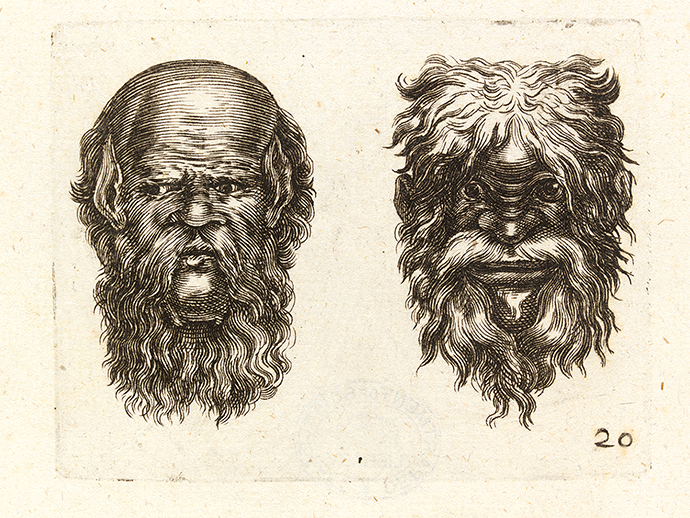

Design for a grotesque mask by Johann Ulrich Stapf © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Witch hunts have always been a tool of those in power. As such, they shed light, primarily, on the needs and fears of the ruling classes. Court proceedings on witchcraft and other devilry, however colorful, rarely tell us much about the accused, even when they show defendants prevailed upon to confess (an admission under duress, after all, generally sticks to the required script). Now, with Carlo Ginzburg and Bruce Lincoln’s Old Thiess, a Livonian Werewolf (University of Chicago Press, $25), a glorious corrective has arrived: the full testimony, translated for the first time, of a loud, proud, self-described werewolf.

It’s 1691, a year before the Salem witch trials, in a small courtroom in what is now Latvia, when our hero, aged eighty or so, saunters onto the scene. He’s there to make a statement in someone else’s case, a matter of petty theft, but the proceedings take a turn when another witness scoffs at the notion that Old Thiess (a nickname for Mat? ss) should be asked to swear an oath, given that he is a known werewolf. His wolfishness, which he affirms without hesitation, thereafter steals the show, and the reader witnesses a rare and fascinating reversal of the familiar dance: instead of being trapped in a double bind, incriminated no matter what he says, the peasant nimbly takes control of the discussion. Rather than deny the charge, he reclaims it and schools the court in an alternative mythology in which werewolves are “God’s hounds,” entering hell regularly, but only to fight sorcerers and protect the harvest for everyone else. When court officials try to get him to repent his presumed pact with the devil, he insists that the devil “cannot bear” werewolves and “has them driven off with iron goads,” and that he himself had his nose broken by a sorcerer a few years back, as they can check in the records of a previous trial. He won’t name werewolf names, and when caught in a white lie or forced to admit that he hasn’t been the most observant churchgoer, he shrugs that he’s old and imperfect, and that “a gracious God might still be gracious to him.”

The transcript of the trial is accompanied by a sampling of historians’ reactions to the case, and readers may enjoy the debates in subsequent chapters: the source material can be read as evidence that bands of bloodthirsty Aryan youth in wolf pelts once roamed Northern Europe by night and laid the foundations of the nation-state (as the Austrian scholar and Nazi Otto Höfler insisted in an uncannily influential 1934 book), or taken to suggest that earlier inhabitants of the region espoused unrecorded shamanistic beliefs about wolf-men (as Ginzburg, a microhistorian and a son of the great novelist Natalia Ginzburg, has argued in several captivating works excerpted in Old Thiess), or treated as an illuminating snapshot of seventeenth-century social and political dynamics (as Lincoln, a historian of religion, more cautiously and rather more persuasively does).

Regardless, the book’s true appeal is the fantastical creature Old Thiess. Though careful to show some tactical humility, at one point he

said that he understood [the matter] better than the Herr Pastor, who was still young, and he lost his temper at the Herr Pastor’s speech, adding that what vexed him so much was that previously no one else had been prosecuted, although he was not the first and would not be the last who had practiced these same things. If it was evil, why had they let others get away with it?

It’s clear from the transcript that by this stage Old Thiess has got the authorities on the back foot, as

the court further urged him to change his mind, alternating kindness and

threats, urging him to recognize the many misdeeds he had committed and his grievous crimes, or at least their bad results.

They’re too confused to convict him, and by the time another judge does so, a year later, anxiety about his status as a folk hero among the peasants is still palpable. He’s given only a few lashes in punishment, and the court’s hope that he might be changed “into an object of noteworthy aversion by public flogging” is so evidently vain, it has a pathos all its own.

“Bowl of Cherries, Rockport, Maine,” by Cig Harvey. Courtesy the artist and Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta

Scapegoats must be as old as human history. In the fifth century bc, Herodotus, who himself recorded rumors of a people who could now and then transform into wolves, cast doubt on Homer’s cherchez la femme account of the Trojan War, claiming that Helen never actually made it to Troy and instead waited out those years stranded in Egypt with a bunch of similarly stolen Spartan property, till Menelaus came to fetch her on the way home. “I am myself inclined to regard [this version of the story] as true,” ungallant Herodotus wrote, “for surely neither Priam, nor his family, could have been so infatuated as to endanger their own persons, their children, and their city, merely that Paris might possess Helen.” It’s also the version Euripides drew from for his 412 bc tragedy, Helen, which has been reinvented by today’s most insouciant classicist, Anne Carson, as a quite different play—Norma Jeane Baker of Troy (New Directions, $12.95). The work was first performed, under Katie Mitchell’s direction, for the opening of the Shed at Hudson Yards last year, and many found it too slight and strange. Admittedly, Carson’s version—in which the heroine, held captive in L.A.’s Chateau Marmont to learn lines for Fritz Lang’s Clash by Night, must escape to New York with Arthur Miller—is both. But it’s all the truer to its source for that: the Euripides play reads more like proto-Shakespearean romance than tragedy. To enlist Helen, rather than the more popular The Trojan Women, for an antiwar theme makes sense especially in the wake of the conflict in Iraq: Helen posits that a decade-long war was fought and a civilization destroyed over a mirage, an eidolon.

It also makes for a more ambiguous Helen—in The Trojan Women, though she defends her life with all the subversive energy of an Old Thiess, she’s very much presented as “a nasty bitch evil-intriguing” (to quote her self-description in Richmond Lattimore’s translation of Homer). Here, Carson does repeat a joke from her translation of Orestesin which Helen is called “that weapon of mass destruction,” but the character is of interest expressly for the conflicting ways she has been interpreted. Hence the link with Marilyn Monroe (aka Norma Jeane Baker). Like witches in the ages between them, both women are symptomatic figures, endlessly accreting the stories a culture wants to tell about itself. (And again like witches, they’re both emblems of misogyny’s evergreen appeal; one of the only jokes in Greek tragedy is supposed to have been Menelaus’ question in The Trojan Women, when warned not to let Helen on his ship, about whether she’d gained weight since last he saw her.)

It’s always a pleasure to watch Carson’s mind at play, and her minor works can have a swift, casual sharpness. Here’s Norma Jeane soliloquizing on “what most people mean by faking it”:

They just mean acting. Well, in the first place, acting is not fake. And, number two, acting has nothing to do with desire. Desire is about vanishing. You dream of a bowl of cherries and next day receive a letter written in red juice. Or, a better example: you know I’m not a totally bona fide blonde . . . so I get a bit of colour every 2 weeks from a certain Orlando in Brentwood and I used to wonder shouldn’t I dye the hair down there too, you know, make it match, but the thing is—talk about a bowl of cherries—most men like it dark. Most men like what slips away.

Naturally this isn’t the real Marilyn, whoever that may have been, and it doesn’t aim to be. Yet Carson’s slapdash Norma Jeane captures some qualities underestimated in too many conjurings of the original—the intellectual energy, Bolshie rebellion, and crude humor that underpinned her blonde-clown antics and helped make them indelible onscreen.

More proof that minor works by great writers can offer particular delights is found in Garden by the Sea (Open Letter, $15.95), a novel by the celebrated Catalan author Mercè Rodoreda (1908–83), who is best known for The Time of the Doves, her account of the inner life of a working-class woman during the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath. Like that novel and the one that followed it, Camellia Street, which inhabits the mind of a Barcelona streetwalker, Garden by the Sea was published in the 1960s, after the twenty years of silence and poverty that accompanied Rodoreda’s postwar exile, but has now been translated into English for the first time by Maruxa Relaño and Martha Tennent. Less ambitious than Doves and gentler than Camellia Street, it treats strong emotion with restraint, often approaching it indirectly via description of the setting’s landscape and its vegetation. The narrator is an aging widower who works as the gardener for a seaside estate, witnessing the seasonal high jinks and occasional tragedies of his wealthy employers and their friends. Set a few years before the Spanish Civil War, it’s full of a melancholy sense of what will last and what won’t: the gardener feels an admiring affinity with the eucalyptus tree, which “does not change . . . with each leaf like a sickle, and each bud a lead box holding a velvety red flower.”

Eucalyptus, by Leon Colinet, from the Encyclopédie de la plante © Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images

The mistress of the estate, Senyoreta Rosamaria, in marrying Senyoret Francesc, appears to have made the same kind of brute economic choice in love that faces Cecília, the narrator of Camellia Street. In Garden by the Sea, a slow-motion melodrama plays out, but, filtered through the eyes of the servants, it’s kept at a distance. Rosamaria’s perspective and those of several other young women are mostly occluded, so that they can each be read in almost as many directions as Helen of Troy or Norma Jeane Baker—though, again, all roads lead, if not to ruin, then to pain and shame. The physical place occupies the foreground—the colors of plants tended or mistreated, and the frame of the vast, ever-changing sea.

Another coastal elegy, still more ravishing in its precision and restraint, is Later: My Life at the Edge of the World (Graywolf Press, $16), Paul Lisicky’s memoir of the complicated idyll that Provincetown offered gay men at the start of the 1990s. The work progresses in small, casually linked episodes, though an intricate structure makes itself felt toward the end—so that the form enacts on the reader some of Lisicky’s inward experience, the perspectival shifts that marked him then and in the decades since. He describes his years there on a writer’s fellowship, surrounded by dunes and by sea on three sides, as well as by a type of queer community that couldn’t exist elsewhere and that was already on the edge of extinction.

What’s affecting here is Lisicky’s preservation of a multitude of subtle, ambivalent feelings, of small kindnesses and cruelties. Nothing is simplified in a bid for universal resonance, and the text is richer for that. It bristles with pinprick observations. At one moment, Lisicky accompanies a Canadian boyfriend on a road trip to visit his family, and the two men must seek a border agent’s approval by affecting not to do so, answering questions “tersely, without any inflection or any eagerness to please. We’re performing what we believe he wants of men, especially two men sharing one car.” At another time, Lisicky catches himself, at the painful end of a relationship, thinking, “I don’t know how to deal with the fact that we’re both probably going to live.” Or there’s the night when he can’t tell his friend, the writer Lucy Grealy, that the sexual performance in her dancing is alienating the gay men around them—this “Sarah Lawrence dancing,” he calls it, that “puts sex in quotes,” while the men keep “some distance between the bodies, because the possibility of fucking is scary, is real.”

Lisicky is disciplined about keeping past and future in their places. On the rare occasions—say, at a friend’s funeral—when “the time line breaks, scrambles,” as he describes it, the effect is profound. Likewise, since he avoids presuming much about other people’s inner lives, the odd exception he allows himself is powerful, such as the train of thought he follows when a man he’s seen around but doesn’t know stands up during a screening of the bland, well-meaning Philadelphia, “crying like a baby, a baby boy, and it wouldn’t be so wrenching if he weren’t such a tough-looking guy, leather vest, Levi’s.” “His friends,” Lisicky speculates, entertaining one possibility among many,

have bailed on him before and they’ll bail on him again, and what should he expect when he’s loved them for their spontaneity and quick passion and unreliability? Dependable people, as he knows, are boring people, and he knows what it’s like to abandon others too.

Though AIDS shadows and distorts everything, Lisicky is also attentive to far smaller pains—the ebbing of desire between lovers, for instance—resisting the temptation to idealize even those people and relationships under immediate threat. Lisicky’s mother, who appears in the opening scene and is mostly absent thereafter, haunts the book. A huge variety of people and even animals are given consideration and respect, including those who appear only on a few scattered pages. You’re reminded that looking closely can be a form of love.