Waiting for the End of the World

Illustrations by Olivier Kugler

Waiting for the End of the World

1.

A man is to carry himself in the presence of all opposition, as if every thing were titular and ephemeral but he.*

I rose long before dawn, too thrilled to sleep, and set off to find my tribe. North from Greenville in the dark, past towns with names like Sans Souci and Travelers Rest, over the border into North Carolina, through land so choked by kudzu that the overgrown trees in the dark looked like great creatures petrified in mid-flight. The weirdness of this scene would, by the end of the weekend, show itself to be appropriate: my trip would be all about romanticism, and romanticism is a human collision with place that results, as Baudelaire put it, “neither in choice of subject nor exact truth, but in a way of feeling.” My rental car’s engine whined as it climbed the mountains. Day was just breaking when I nosed down a hill to Orchard Lake Campground, where tents were still being erected in the dimness.

I had come to this place just outside the town of Saluda, forty miles south of Asheville, for Prepper Camp, a three-day weekend gathering that would draw twelve hundred people to learn how to survive what they call TEOTWAWKI, or The End of the World as We Know It. The camp was started in 2014 by a husband-and-wife team, Rick and “Prepper Jane” Austin, celebrities in the doomsday field. Its sixth iteration would take place on a late-September weekend with downpours forecast for all three days—I had bought waterproof everything—but which would turn out to be so uncannily hot that it could have been full-blown summer.

In a still-dark field, a man wearing an orange shirt that read i’m a parking cone guided my car into place. The sky in its slow dawning revealed high blue shards of clouds, hills rich with goldenrod, a pond scummy at the edges. I reclined my seat to rest and to watch the preppers pass by. They were mostly male, between their late fifties and early seventies, with such an abundance of paunch that the only possible reaction was to marvel. These men were straight-up gravid. They seemed proudly working-class and most were former military, a fact made clear by the patches and medals they wore like over-the-hill Eagle Scouts. Nearly everyone was white. Over the weekend, I would count exactly nine visibly non-white preppers, three of whom were presenters. The camp’s organizers were surely aware of their target demographic; one volunteer had made up a little cartoon character named Pappy Prepper, a bearded old white man in camouflage pants, who in a promotional video for the gathering sang a song to the tune of “My Favorite Things”:

Ways to store water and defensive shooting

Grow secret gardens and stop folks from looting . . .

As the day came on around me, I listened to the human parking cone cheerfully directing traffic. “You handicap?” he shouted toward a giant pickup.

From the truck there was a hemming. At last, one of the men inside shouted, “He’s too proud to tell you he’s a wounded veteran.”

“Aren’t we all!” said Parking Cone.

A river of grim and portly old men flowed by, and I felt shy in my civilian womanhood and comparative youth. I waited until I saw a pair of women in hiking boots and flak vests, and gathered my courage to follow them out into the cluster of tents optimistically called the Prepper Camp Shopping Mall. Nearly all the instructors and speakers this weekend would be unpaid, trading their expertise for the opportunity to sell their books and other goods and to market their survivalist services. There were tents peddling batteries, huge water-storage tanks, medical equipment, army-navy surplus, and something called colloidal silver, which purportedly had antibiotic properties. (When I asked how it worked, the woman selling it gestured vaguely and said, “It just does!”) An angel-faced woman named Mary in a doeskin skirt advertised a permaculture school. An eager young man from a company called Ten Foot Wall sold a USB drive that can create virtual, hermetic computers within your computer, in order to block people and software from tracking your online movements and purchases. There was a table displaying weaponry, and propped at the edge of the nearby pond, there was a target in the shape of a human body. Even early in the morning, the pond was full of children tooling around in kayaks and canoes.

Prevalent iconography included eagles, crosses both Celtic and Latin, the Don’t Tread on Me snake flag (aka the Gadsden flag), and the Confederate Stars and Bars. There were MAGA hats galore, so many that by Sunday I would lose the thrill of fury at seeing one. There were T-shirts bearing such phrases as: we are the virus they want to destroy; pro-god, pro-gun; live free or die hard; the calm before the storm. The right shoulder sleeves of many shirts featured backward flags, which I took to have sinister intent until I discovered that this was a convention of military uniforms, meant to show the banner flying as though in a breeze. My favorite tee depicted Ronald Reagan unbuttoning his dress shirt to reveal a chest made out of the American flag.

A sweet-faced woman beaming over a basket of apples invited me to take one. come hear a dramatic reading of the best-selling book in history! a sign behind her read. The Bible? I guessed. Her face fell a little, but then she laughed. She was pushing her husband’s self-published disaster-survival fiction series; she’d put up the sign to lure people in. I said I’d love a reading. He, one Timothy A. Van Sickel, was a good sport and read to me in a sonorous voice from Genesis, and then from his own work. He read very nicely, I told him. One day three years ago, he said, he’d come home from his contracting job with the epiphany that his true mission was fiction—survivalist fiction, in particular. He’d published five books since then. Five books in three years! I marveled. I felt for him: he had the eager, shy desperation all authors feel when they have to hawk their souls in public. I wanted to tell him that boy howdy I could empathize, but I couldn’t out myself so early. Preppers are notoriously private, keeping their end-of-the-world plans so ferociously guarded that they even have a name for their secrecy: OPSEC, operational security. Self-published writers could be trusted because they worked outside the system; a literary insider in the preppers’ midst might be considered a double agent. Which of course, I had begun to see, I was.

It was already too late to blend in, though. I hadn’t known before I arrived that at Prepper Camp camo and olive drab were the markers of belonging. Even very old ladies who certainly had never seen active duty wore camouflage sun hats and plastic clogs. I watched the people around me with a creeping sense of dismay. With a jolt, I saw that I was also being watched in return. I understood then that being a woman alone in this place was already unusual; far worse, I was wearing East Coast liberal-arts-college clothes, a Patagonia fleece, and a North Face backpack. I looked like a good bourgeoise, the kind of woman who drinks kombucha and does yoga and reads Harper’s before bed.

A blond giant with a militiaman’s face and two sullen-looking girls in their early twenties with blurry blue tattoos on their arms milled nearby. They were staring me down hard. “Well,” said the Viking. “Guess it takes all kinds.” The girls snorted. I blushed with a shame the intensity of which I hadn’t felt since I was a bullied middle schooler, and fled to the white open-sided tents around the pond where the classes would be held.

2.

I hope in these days we have heard the last of conformity and consistency. Let the words be gazetted and ridiculous henceforward.

Perhaps I should have expected to feel wildly out of place at Prepper Camp. I am a vegetarian agnostic feminist in a creative field who sits to the left of most American socialists: I want immediate and radical action to halt climate change; Medicare and free public higher education for all; abortion pills offered for pennies in pharmacies and gas stations; the eradication of billionaires; the destruction of capitalism; and the rocketing of all the planet’s firearms into the sun.

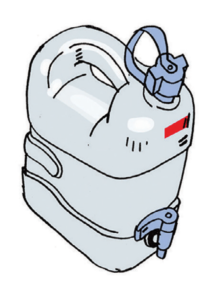

And yet I am also, in the darkest corners of my heart, a doomsday prepper myself. I live in Florida, where hurricane season runs officially from June through November, and both the Gulf and the Atlantic are regularly beset by calamitous storms. It just makes sense, living on that vulnerable spit of land between two roiling, unpredictable bodies of water, to ensure that one’s house has at least a two-month supply of food and at least nine modes of procuring drinking water in case society breaks and city services are cut off. (My family’s are: a rain barrel [1]; filtration straws [2]; a sun oven to pasteurize water with solar heat [3]; a Sawyer Squeeze water-filtration system [4]; a hundred-gallon airtight bladder, to be filled at the first sign of trouble [5]; a gas grill for boiling [6] and, in a pinch, dew collection [7]; iodine tablets [8]; and a tub with a tarp over it to let evaporation run off into a clean bowl [9].) We have medical kits in both of our cars and bug-out bags prepared for each family member, in case we have to flee in minutes. This kind of preparation is all still somewhat in the realm of the normal. Less so: I have negotiated for my family a hideout in New England with a fully stocked tiny house that has a woodstove and solar heat, with forests around it for firewood and cleared land for gardening. There are established fruit trees, water sources, and plenty of wildlife, if necessity forces us to set aside our moral revulsion and kill our fellow creatures for sustenance. In both Florida and New England, I have libraries of foraging and food-storage books; if I don’t always have direct knowledge, I know where to find it. I take boxing classes for self-defense; I have made my children learn archery. I have signed them up, for years, with the Boy Scouts so they will know how to build fires and handle knives safely, even though its soft-focus, quasi–Hitler Youth nationalism makes me queasy.

It is not that I have horrendous visions of an electromagnetic pulse taking out the world’s power grids, or of oil and gas production ceasing and leaving seven billion humans to revert to the pre-industrial era, or even of World War III being launched on an otherwise normal day because Trump can’t resist the urge to push the big red button. But I can see how fragile the institutions of society are and how ever-more frayed they are becoming under the weight of late-stage capitalism. I see in vivid near-hallucinations how climate change will exacerbate every human-rights issue until we cannibalize ourselves. There will be mass displacement, pandemics, tribalist violence, genocide, food and water scarcity, deforestation, desertification, cities underwater. The warming planet, the mass extinction that has already begun, the fact that I need my children to live at least beyond the span of my own life: these things murmur in my ears, give me waking nightmares. Such profound eschatological horror can only be slain by action. I ready myself for as many possibilities as I can so that I may keep my raging anxiety under control.

And so, in the depths of my climate-grief insomnia, I read my little library of books and go online to prepper blogs and Reddit threads to find new and more efficient modes of survival. But it is lonely to lurk on the internet, a diabolical invention that isolates people even as it feigns connection. Also, a novelist is already a professional autodidact; when it comes to the survival of the human race, I want to be told the things I don’t know enough about to seek them out myself. Hence Prepper Camp. I was so excited about the tidal wave of information I would be facing among my doomsday peers that I couldn’t sleep for a week beforehand. All that weekend, my children would tell my friends in Florida with wild grins that no, I wasn’t home: Mommy is at Apocalypse Camp!

3.

An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man.

When I was still at home, the classes on the schedule had seemed a bizarre blend of two types: hippie homesteading and paranoid militarism, without a great deal of intersection between the two. I was far more interested in the hippie classes, as they might give me useful practical knowledge and would not involve discussion of killing my fellow humans. One of my first classes was “SHTF (Shit-Hits-the-Fan) Intelligence,” which I believed was going to be about the extremely rarefied things one needed to know in a catastrophe: how to plan escape routes ahead of time, where to buy laminated maps, how to use a compass, and how to gauge whether to stay put or flee depending on what one understood of the catastrophe at hand. Instead, the instructor, a former soldier named Samuel Culper who heads up an organization called Forward Observer, described how his group tracks civil unrest via social media, police scanners, and on-the-ground observers.

I couldn’t understand how tracking protests against police violence from a tent somewhere had anything to do with prepping. But I regained some sense of my enthusiasm by proceeding to classes on permaculture, which I believe in deeply. Industrial agriculture is poisoning the planet and our bodies; we’re all better off growing as much of our own food as possible. Our host, Rick Austin, sweating through his khaki shirt in a circle from shoulder to sternum, gave such a thrilling talk about “Secret Gardens and Greenhouses” that I bought his book, Secret Garden of Survival, at the prepper mall afterward. Austin had been a commercial farmer, growing apples in New Hampshire and oranges in Florida, when he realized that agriculture’s traditional rows of plants were not designed for the plants’ sake, but for the sake of the machinery that sows and harvests it; in a post-doomsday world without heavy machinery, and with smaller-scale, nonindustrial agriculture, farmers would do better to plant crops the way crops want to grow.

I couldn’t understand how tracking protests against police violence from a tent somewhere had anything to do with prepping. But I regained some sense of my enthusiasm by proceeding to classes on permaculture, which I believe in deeply. Industrial agriculture is poisoning the planet and our bodies; we’re all better off growing as much of our own food as possible. Our host, Rick Austin, sweating through his khaki shirt in a circle from shoulder to sternum, gave such a thrilling talk about “Secret Gardens and Greenhouses” that I bought his book, Secret Garden of Survival, at the prepper mall afterward. Austin had been a commercial farmer, growing apples in New Hampshire and oranges in Florida, when he realized that agriculture’s traditional rows of plants were not designed for the plants’ sake, but for the sake of the machinery that sows and harvests it; in a post-doomsday world without heavy machinery, and with smaller-scale, nonindustrial agriculture, farmers would do better to plant crops the way crops want to grow.

Austin showed pictures of the evolution of a garden on his mountainside homestead, first stripped to the topsoil, then planted in “guilds” of fruit or nut trees surrounded by symbiotic plantings of berries and vines and useful nitrogen fixers. The result within only a few years was a garden so lush and productive it now doesn’t look like a garden, doesn’t need weeding, watering, pesticides, or nutrients, and provides many pounds of food per square foot.

Gladness had taken root in me again. Next was a talk on “Frugal Homesteading” by a man who would end up being my favorite of all the instructors, John Moody, a goofy, smart guy who quickly got the audience on his side by calling one of the volunteers passing by a “discount Fabio.” Moody told us he had once attended seminary; had cured himself of duodenal ulcers with food; and had bought a farm with his family that initially had less than 0.5 percent viable soil and was now a functioning homestead. He was one of the few instructors who seemed willing to think beyond standard prepper lore. One of his tips was that survivalists often prioritized the wrong things. They may spend years prepping for an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) from the sun that would in theory take out communication systems and thus all of civilization, though, as Moody said, “Most people in this room are going to die of diabetes and heart disease.” At this, the audience gasped in audible dismay.

But to me, it felt a little validating to hear Moody say this: I had been astonished at how physically unfit nearly every attendee at Prepper Camp appeared to be. Even many of the younger preppers were obese, and health problems were visible and rampant. There were more canes and hiking sticks than athletic bodies. Moody said that when he heard an unfit man bragging, “I’m up to seven Glocks,” he wanted to reply, “Well, sell two and get a membership to Gold’s Gym.” Did people think they could fire a gun into a tornado, a storm surge, a wildfire? Most attendees very clearly couldn’t run a single mile to escape disaster, and fitness is among the most essential tools for flight. (For that matter, I wondered why there were no classes on how to get sick or disabled people to safety. Were they planning to leave Grandma behind with a semiautomatic and a fistful of beef jerky and hope she’d still be there when they crept back a few weeks later?)

Next up was “Anti-kidnapping and Hostage Survival,” where two “barrel-chested freedom fighters,” a man named Billy Jensen (former Green Beret and surveillance officer turned antiterrorism instructor) and a woman named Check Freedman (held hostage and raped at sixteen, she’d become a federal agent and “police asset”) taught us how not to get taken. I looked around the room at the aged and the infirm and the unfamous, the salt of the earth, wondering who, exactly, the intended audience was for this talk: Weren’t the people who got kidnapped usually journalists, or the wealthy, or the children of the powerful?

At “Getting Your Head Right,” Benjamin Raven Pressley wore an olive vest with spangled wings on it, said he was part Cherokee, and called himself a “spiritual guide coach.” At “Gold and Silver,” Keith Iton, one of two African-American presenters I noted, urged us to collect gold and silver for the End Times. At “Homestead Herbals,” Suzanne Upton free-associated about which herbs were good for which diseases. Basil for high cholesterol, Spilanthes for numbing, bloodroot for warts, dandelion for the liver, pine pollen for androgens, sweet gum for the lungs. And so on, for an hour.

Finally, at the “Sun Cooking” demonstration, there was the weekend’s first (and, it turned out, only) discussion of concerns outside the scope of the individual. Paul Munsen, president of Sun Ovens International, showed off his miracle cookers, which need only solar heat to work. In addition to his descriptions of baking bread and boiling eggs with the sun, he talked about climate change; deforestation; and the fact that 2.5 billion people today still cook over fires, which takes a huge amount of time, contributes to environmental collapse, and gives people respiratory diseases. He had met Nelson Mandela and spoke fondly of him. He even said the word “progressive” as though it were a good thing, bless him. I was shaken to realize that this was the first discussion of climate change I had heard all day; that though there was plenty of talk about defense against kidnappers and nuclear, biological, or chemical warfare, the actual calamity bearing down on humanity, that great elephant in the room pressing us all to the wall, had been almost entirely ignored.

4.

I tell thee, thou foolish philanthropist, that I grudge the dollar, the dime, the cent, I give to such men as do not belong to me and to whom I do not belong.

During the brief dinner break, I went with a misty head to set up my tent in the overflow campground. The other preppers were just hanging out; they watched without speaking as I struggled with my equipment. I tried to be as quiet as possible—a mouse. God forbid they search my camp when I was gone, I thought. They’d find books of poetry. I began to think that it was perhaps an oversight to have brought no weapons, not even a multi-tool, to this place that now seemed very obviously teeming with them.

Because I didn’t trust myself to make a campfire while others were watching, I had brought food that I didn’t have to cook: oranges, granola and almond milk, peanut butter and jelly. I ate in my tent, and with my hand-crank flashlight, I read Rick Austin’s book. It didn’t take more than twenty minutes; I finished pretty bummed out that I had spent $35 on the thing. Though it contains some good ideas, it suffers the lack of editorial attention typical of self-published works, offering only the vaguest recommendations, with eccentric punctuation and terrible photography, and it included the only instance of overt racism (putting aside the MAGA gear and Confederate flags) that I saw all weekend: a photo of the “zombie hordes” that Rick Austin believes will be swarming the land and stealing his food during the apocalypse, credited to the Associated Press, actually depicts desperate brown people wading with their children to dry land.

I thought back to something Jensen had said at the anti-kidnapping class: “As a soldier, though I’m a Christian, I have to dehumanize the people I’m fighting against.” All day, I had been set back on my heels by the survivalists’ suspicious attitude toward others. You could only treat suffering people as “zombies” if you stripped them of all their humanity.

5.

To be great is to be misunderstood.

I went back out into the dusk, sad and lonely. The air was hazed with smoke from campfires and smelled of delicious hot food. The campers had hooked up their phones and speakers to electrical outlets and were playing classic rock while they cooked. Boxer dogs seemed to be the favorite animals of these survivalists. Little kids rode along zip lines. The faint smell of sewage came off the pond, and a tulip tree by its edge was shedding yellow leaves. Older children jumped off the dock; parents called for them to come back to eat dinner.

It would all have been so ordinary if it hadn’t been for the End Times hanging like a sword over our heads.

The first part of the night’s official entertainment was the episode of National Geographic’s Doomsday Preppers that featured the Austins. It was called “You Said It Was Non-Lethal,” and in it Rick and Jane describe their decision to flee suburbia after their neighborhood’s economic ruin—to the point that some nearby single-family homes were being shared by four and five families and Jane was carjacked while leaving work.

Watching the episode, I felt a little hurt on behalf of the pair: the tone of the show was impressed—by the preppers’ ingenuity and the genius of their great hidden garden full of food—but it was also very clearly poking fun at them. Jane came across as wild-eyed and manic, showing off a hygienic invention in case toilet paper is no longer available in the future: a pump-action garden sprayer filled with an herbal tisane and called a “heinie hydrant.” Rick and Jane were shown in goggles, thick rubber gloves, and respirators, making a Mace-like spray out of extremely hot peppers from their garden; then weeping and spitting and hacking when their protection proved insufficient. At the end of the episode, the couple was given a grade of 89 out of 100 for preparedness and a twenty-month initial survival time, which, I think, made the onscreen Rick a little sad. I don’t know whether the Austins had registered the ridicule in the way they had been depicted, though if they had, I have a hard time understanding their screening the episode for a group of people who admired them.

Watching the episode, I felt a little hurt on behalf of the pair: the tone of the show was impressed—by the preppers’ ingenuity and the genius of their great hidden garden full of food—but it was also very clearly poking fun at them. Jane came across as wild-eyed and manic, showing off a hygienic invention in case toilet paper is no longer available in the future: a pump-action garden sprayer filled with an herbal tisane and called a “heinie hydrant.” Rick and Jane were shown in goggles, thick rubber gloves, and respirators, making a Mace-like spray out of extremely hot peppers from their garden; then weeping and spitting and hacking when their protection proved insufficient. At the end of the episode, the couple was given a grade of 89 out of 100 for preparedness and a twenty-month initial survival time, which, I think, made the onscreen Rick a little sad. I don’t know whether the Austins had registered the ridicule in the way they had been depicted, though if they had, I have a hard time understanding their screening the episode for a group of people who admired them.

Doomsday Preppers was followed by a feature film: 2018’s Death of a Nation, by Dinesh D’Souza, a work whose promotional materials featured an image of Abraham Lincoln’s face split with Donald Trump’s, the man least like him in temperament and policy ever to set foot in the White House.

The film’s premise is that, just as Democrats worked against Lincoln, they are now working to retard the social progress represented by Donald Trump. When we reached the part presenting Adolf Hitler and the Nazis as liberals—“this is done by the do-gooders . . . the people who want to improve society”—I sat in the viewing tent surrounded by angry survivalists, swarmed by mosquitoes, and felt my grasp of reason and history assaulted.

And as the spectacle proceeded, I found language for the questions that had been growing in me all day. What in the world did right-wing conspiracy theories have to do with preparing for disaster? What was the purpose of this exhibition of baseless propaganda? I looked around me, but the faces I saw were rapt: Why did it seem that I was the only person who saw how incredibly stupid this film was?

My loneliness drifted into fear when I imagined what would happen if my poker face slipped and the preppers could see all the disdainful liberal thoughts bouncing around in my head.

At a certain point, something began to seem more wrong with the film than merely its lies. The music was pompous and loud, but the dramatization of Hitler and Eva Braun’s suicides took place with no explanation, as though it were an old-time silent movie. D’Souza was depicted onscreen first during a reenactment of his childhood in India; then as the adult D’Souza in New York City, speaking gravely. This is when it became obvious that some of the strangeness of the film was due to a technical problem: the spoken track was missing entirely, and only the background music was playing. D’Souza just flapped his lips. This felt appropriate.

I left before the volunteers resolved these difficulties, trudging with my windup flashlight through the darkness to my campsite. I had set myself up between the tiny one-person tent of a man named Buddy, a construction worker from New Jersey who would later show me his femur-length machete, and the larger tent of a middle-aged man named Troy and his three bearded sons. Troy and Sons had a campsite so elaborate—with tables and chairs and a gas grill and fancy outdoor cots and lanterns—that I envied them. They were playing cards and eating filet mignon under golden lamplight. We spoke briefly, but all I wanted was to be alone, to let my pretenses fall away and read my goddamn poetry by flashlight. Once inside my own tent, I began shaking with relief after the long day of pent-up anxiety—that of being recognized and called out for the prepper imposter I had, this day, become aware that I was.

6.

All things are dissolved to their center by their cause, and, in the universal miracle, petty and particular miracles disappear.

The campsite was loud, and it was impossible to sleep given the inadequate pad beneath me, the giant ants crawling over my hands and neck, and my neighbors on both sides chatting away happily: What’s the diff between kerosene and propane? I heard. I got some extra steak if you want, I heard. My credit has been froze for three years, I heard. Something way off in the woods screamed girlishly and either Troy or a Son of Troy grunted “Fox” in explanation. Raise. Call. Fold. They were playing poker. But the thrill in the blood from the screaming fox made me think of emergencies, of Rick and Jane in their armed 360-degree eagles’ aerie in their overgrown Garden of Eden, with the chicks and coffee plants in the hidden greenhouse, and of what they would do if civilization really were blown to smithereens. It went against everything I knew about the essential altruism of humanity to imagine one of those people taking a potshot at some bewildered hiker who had gone up the wrong road. How terribly lonely it would be for Rick and Jane waiting out the apocalypse with their animals.

I wondered what exactly could bring a person to that point where they were willing to hole up and just stop caring for their fellow man. One thing I do know about humans is that the stories we tell about ourselves are the people we become. And the American narrative of macho self-reliance, which the preppers had been preaching all day, is an extremely old story; it is, in fact, one of the oldest stories of this hemisphere, emerging out of the moral gymnastics it took for ostensible Christians to sail across the Atlantic and commit acts of genocide, rape, and war against other human beings in order to allow themselves to enslave them and to seize and control land that was never their own. These new Americans needed a way to frame their actions as heroic and inevitable, and they found it in the narrative of the noble frontiersman, the solitary figure pitched against the exigencies of unpredictable nature. This type existed before Robinson Crusoe, notably in real-life survival tales told by captured, enslaved, or castaway men and women; but it was Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel—about a seventeenth-century slaver capsized and stranded for twenty-eight years on an island near the Orinoco River, in South America—that solidified the specimen into an archetype. It’s no accident that the book is counted among the first English novels: it is a work of purest fiction—as fictional as Dinesh D’Souza’s movie, though both were packaged as documentaries.

It is easy to be intoxicated by Robinson Crusoe, the character, even if one sees, through twenty-first-century eyes, the book’s broken moral compass. In his extreme emotional continence, inventiveness, almost impossible industry, he is the pinnacle of self-reliance. The reader—wooed by these virtues, which we have been told repeatedly are the height of manliness—cares deeply about Crusoe’s plight. We read anxiously of his parrot, his struggles with gunpowder, the way he slowly builds a miniature England on the island he makes his.

And it is easy in all this wonder to forget that Crusoe’s predicament began with a mission to bring slaves back to the New World; he was an unapologetic murderer of the island’s cannibals; he imposed his language and religion on his young slave, Friday. Crusoe reappeared by other names in later fictions: in the stories about the historical figures Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, who both became elevated to legend through folklore; in James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, returning as Natty Bumppo, aka Hawkeye, aka Leatherstocking, aka Deerslayer. Bumppo was also called La Longue Carabine—being a manly man, of course his rifle had to be enormous. Out of the West came an equivalently violent gunslinger: a type that was taciturn, competent, and living beyond the scope of social systems. John Wayne; Cormac McCarthy’s characters. In these pages in September 1968, Larry McMurtry wrote: “Cowboys are romantics, extreme romantics, and ninety-nine out of a hundred of them are sentimental to the core.” (This tracks with the preppers at camp. Although ostensibly preparing for the future, they were mostly concerned with the monsters of former eras—nuclear war or the loss of the electrical grid—not the far more monstrous contemporary threat of climate change ending all human life.)

In non-fiction form, this romantic strain metamorphosed into the peculiar, homegrown utopian philosophy of transcendentalism, which gave flesh-and-blood Americans a codification of the laws of manhood. A notable inspiration for preppers, and a foundational text for the kind of libertarians who read, is Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1841 essay “Self-Reliance.”

In my tent, I pulled the work up on my phone and slowly reread it.

Emerson was still a relatively young man of thirty-eight when he published the essay, and it’s so full of passionate disdain that I have a hard time reading it in anything but a Holden Caulfield voice. But this is unfair. “Self-Reliance” is a profoundly poetic work, strange and circuitous, full of startling imagery and chockablock with aphorisms so constantly recycled in American daily life that a reader can feel déjà vu in encountering the full text for the first time. Emerson’s essay holds up the self as the bedrock from which all other authority rises. Those who view Emerson as a libertarian prototype cite his glorification of the individual, as when he says, “The only right is what is after my constitution, the only wrong what is against it”; his opposition to institutions like government and religion; and his idea that community is a distraction. But I think this distills Emerson’s argument into something far smaller than its actual, and truly gigantic, oddness. Emerson’s argument is less libertarian than it is anarchic. He is not after the deification of the self—self as sun around which the planets of other people must orbit—but rather the radical de-emphasis of the institutions that bind and constrict an individual’s true use and purpose. Emerson’s philosophy is the opposite of the libertarian celebration of greed and selfishness and social Darwinism, the ideology’s fixation on personal freedom to the detriment of social security or collective advancement: Emerson posits a sort of Buddhist attention to the moment and awareness so deep it calls into question the structures that inhibit social change, the very things that lead to inequality. Self-reliance is not the same thing as self-interest.

7.

Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members.

I was bleary from sleeplessness, smelly from not wanting to go into the showers used by a few hundred other souls. I ate with glum slowness; I had not talked to anyone for longer than a few minutes in over forty-eight hours, and my solitude was wearing.

The day before, I had been so gladdened by John Moody that I nearly ran to the first class of the day—his discussion of elderberries. He quoted Pliny the Elder, Hippocrates, and Hans Christian Andersen. He explained that the Count from Sesame Street had a historical basis: in medieval times vampires were thought to have OCD, and if you put elderberries on your windowsills, any vampires would be so entranced by counting them that they wouldn’t come into your house. He so beautifully extolled the endless medical and diet-related benefits of elderberries that I was seduced into believing that all people with even ten square feet of soil should be growing them. (I bought his book, and back at home, I ordered elderberry plants.)

Then I went on a “Wild Edible Survival” foraging walk with Richard Cleveland of the Earth School in nearby Hendersonville: we moved a few feet down the road as a mass of sixty or seventy people and plucked and sampled sassafras, plantain (nature’s Benadryl), dandelion, sour grass, and violet.

At “Concealed Carry and Defensive Shooting,” the instructor, David Stutts, talked about “playing with guns,” and showed a video in which a child who looked to be under the age of twelve shot at a silhouette, from a table, as though he were in a restaurant. It filled me with nausea and grief; why should children be taught to kill other humans? Stutts also said that after homeowners had incapacitated robbers or looters by shooting them in the legs, and the malefactors were on the floor, bleeding, the vigilante homeowners could decide for themselves whether to wait for the police or just “finish the job.” He made it clear with a big clownish wink what he would do.

“How to Build a Medical Kit” was presented by the Skinny Medic, a boyish paramedic who had named himself when he weighed 120 pounds following a high dose of prednisone. Now that he was healthy, he joked that he should be called the Dad Bod Medic. He listed what ought to be in a medical supply kit: headlamp, box of gloves, shears and hemostat, Betadine or iodine, saline flush, superglue, horse tack, Ace wraps, Combat Application Tourniquet, stretch gauze, plastic bag to seal chest wounds, Mylar space blanket, generic pain meds, and so on. This felt deeply helpful; my fingers ached from taking notes.

“How to Build a Medical Kit” was presented by the Skinny Medic, a boyish paramedic who had named himself when he weighed 120 pounds following a high dose of prednisone. Now that he was healthy, he joked that he should be called the Dad Bod Medic. He listed what ought to be in a medical supply kit: headlamp, box of gloves, shears and hemostat, Betadine or iodine, saline flush, superglue, horse tack, Ace wraps, Combat Application Tourniquet, stretch gauze, plastic bag to seal chest wounds, Mylar space blanket, generic pain meds, and so on. This felt deeply helpful; my fingers ached from taking notes.

Thunder sounded overhead. The skies darkened, and a very light rain drizzled down. Black flies descended with the rain and began to bite.

At my next class, “Primitive Wilderness Survival,” I learned how to go “beyond prepping to recognize and utilize the resources in nature”: how to find water from the source and build a debris shelter. The instructor joked about his worst night in a shelter: “I slept like a baby—I cried all night and pooped my pants.” On to the Old Grouch’s “Simple and Quick Shelters,” where I learned how to make a different kind of shelter out of a poncho.

My last class of the day was “Psychological Warfare.” The instructor was a super-fit black man named Hakim Isler, whose movie-star charisma made sense when I learned that he had been on Naked and Afraid and other survivalist television shows; he calls himself the Black MacGyver. He, too, was former military, from the SERE—or Survival, Escape, Resistance, and Evasion—school, a combat veteran, and a fourth-degree black belt in To-Shin Do, which had led him to write a book called Ninja Survival.

Isler took us through the idea behind psychological operations, or psyops, which he learned when he was in MISO, or military information support operations. He spoke of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the five tenets of survival (there’s always an agenda, know what makes you tick, psyops is a two-way street, take notes, be flexible and open to change), and the four strategies of the field (fortify, align, divide, and overcome).

I began to think that perhaps Isler was himself here to engage in psyops—to discover what makes preppers tick, to track their psychology, to understand the needs and weaknesses of this community, with the ultimate aim of somehow using that knowledge. Perhaps this class was a way of hiding in plain sight, being so brazen about his presence that nobody would ever suspect him of having an agenda. I thrilled to the idea; I felt, for the first time since the disillusionment of the day before, that there might be someone in this place who wasn’t a libertarian. Perhaps I wasn’t as lonely in my politics as I had felt. Or perhaps I was losing my mind.

8.

The doctrine of hatred must be preached as the counteraction of the doctrine of love when that pules and whines.

Another sad dinner of PB&J and oranges, and back into the night to hear the keynote speaker. I needed all the resilience I could muster. The speaker was a man named Curtis Bowers, whose films, Agenda: Grinding America Down and Agenda 2: Masters of Deceit, tracked (to quote Prepper Camp material) the

history of the liberal, deep state, communist party agenda, to fundamentally change America to a communist country from within. The people behind this Agenda had a very detailed, 50 year plan, to destroy America, and they have achieved almost all of their goals from the 1960’s to today. Come to our Key Note Address to find out how we can save this country from the liberal socialist Globalist agenda.

There was almost too much to dislike in this description, beyond the fact that the word “globalist” has long been an anti-Semitic dog whistle. I knew I would have the urge to flee, so I planted myself in the center of the audience, where I would be surrounded by people eating up this bullshit and would have to remain seated until the end.

Curtis Bowers came out. He was a mostly bald man hiding his head under a baseball cap, a former Republican state representative in Idaho, the owner of fondue restaurants, and the father of nine homeschooled children. “Doing my part to populate the earth,” he joked, to applause.

He talked about reading the 1958 book The Naked Communist and realizing that the Communists had a long-term plan to destroy the “culture of morality” of America and to get people to “accept homosexuality and feminism.” He said in a voice rich with sadness that he couldn’t take his boys to Walmart because the covers of magazines show what used to be considered pornography.

Other notions Curtis Bowers promulgated that night were: That the Communists planned, as a part of their agenda, to destroy “beautiful” art, meaning figurative art, and to institute abstract art in its stead. That Senator Joseph McCarthy “did not destroy a single person’s life.” That public-school teachers are trying to indoctrinate students with Communism.

At the end of the talk, Bowers got a standing ovation.

I steamed back to my tent and was kept awake by the ants, the night birds, and the neighbors, who were having a giant party at a campfire. I would have attended if I hadn’t been too frightened of being inadvertently shot by a gun hoarder who’d had too many beers.

9.

Every man discriminates between the voluntary acts of his mind, and his involuntary perceptions, and knows that to his involuntary perceptions a perfect faith is due.

Sunday morning came cool and sunny. I ate my granola with almond milk and packed my rental car with a glad heart. The insomnia and constant orange-alert-level anxiety were wearing on me, and I had decided to run away to a hotel in Greenville after the day’s sessions, to luxuriate in a pool and a soft bed and order room service. I would enjoy the benefits of modern society for as long as shit and fan remained far from me. As I was rinsing out my bowl, I heard an electric crackle and looked up to see two police cars rolling through the grounds.

Someone’s in trouble, I thought. Then, in one of the more surreal moments of my life, I watched them stop beside my rental car. One cop got out with a hand on his holster. “This car’s been reported stolen. You steal this car?” he said. No no no no no, I absolutely did not, I told him. I showed him the Hertz rental agreement.

All around me, preppers peeped out of their tents and pickup trucks to look at the cops, then at me, that weird lady who came to survivalist camp all alone, who kept herself quiet and apart, who had now invited cops into a camp for a group of people who had, let’s say, a fraught relationship with governmental authority. I thought of the weapons they surely had hidden in their cars and campsites, how so many of those were probably untraceable if not totally illegal. One of the policemen called dispatch to try to figure out what was going on. Someone in Atlanta, he was told, had reported that her boyfriend had stolen her car. I said that I wasn’t in Atlanta, I don’t have a boyfriend, I have a husband in Florida, and I’d been parked there since Friday morning. “She has, we’ve seen her!” one of the neighbors yelled across the way. OnStar had tracked my rental car down and disabled it remotely; no matter what, I was stuck until everything played out. One of the police officers was Sergeant Jeff Smith of the Polk County sheriff’s office, a handsome blond man with an athletic build who was courteous and kind. I grew a little crush on him, but that may have just been Stockholm syndrome. Jeff and I chatted between his bouts of calling here and there, Atlanta, dispatch, the cop who’d received the original call. Nearby, tent after tent was disassembled, cars rolled away, men speed-walked up the hill, fleeing the proximity of the law. Troy, in the next campsite over, heard me say that I was a writer, and his face darkened; then he and his sons took off with nary a word to me.

Three hours passed. I missed the Sunday Christian service in the field, which would have been lovely; I’m a fan of collective action of many kinds. I missed the classes I had wanted to take that morning: “Undercover Soccer Mom,” “Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Defense,” “Escape from Restraints.” How ridiculous it all was. Here I stood (a good liberal!) among the few attendees at Prepper Camp glad to pay hefty taxes for such agents of the nanny state as police officers, and yet I was the one who had somehow found herself squirming under the nanny state’s attention. As far as the sergeant could tell, the mess-up was entirely Hertz’s fault: likely some functionary had mistyped my car’s VIN or license plate number. OnStar turned my car back on at last. The policemen drove off. Later, instead of apologizing, Hertz put me on a list of people banned from renting cars in the United States, for neglecting to report my car as stolen.

After the cops left, I felt vulnerable, the object of the intense curiosity of the remaining preppers at camp. I couldn’t bear the weight of their suspicion, and I was so weary I knew my shell would break under questioning. I had a vision of myself being hauled before a kangaroo court presided over by Rick Austin. Passing under the radar had been hard. Now that I had inadvertently brought the pigs to their turf, I did not feel entirely safe. Before the police cars’ dust cloud blew away, I too zoomed off, down the mountain, returning to the glories of civilization for as long as we still have it.

10.

But now we are a mob.

I was terribly sad. I had found my people, perhaps, but I had not found my tribe.

It should not have been a surprise to me—though it was—how rarely actual facts were invoked at Prepper Camp: instead I had heard a great deal of fear mitigated by practical-seeming ideas, lots of baseless venom spat in the direction of imagined liberals, but almost no science to give weight to any assertions, no analysis of the larger state of the world, no evidence of statistical knowledge. Survivalists had revealed themselves to be romantics. Prepper Camp was a castle built on emotion: fear of the inchoate other was so great that the survivalists felt justified in being prepared to kill other humans to protect their material goods.

But scientists and historians who study catastrophes for a living have long known that there is, in fact, very little antisocial behavior that takes place after disasters. Rebecca Solnit’s extraordinary book A Paradise Built in Hell describes in great detail the collective sense of “immersion in the moment and solidarity with others” that follows large-scale calamities. The common person rises to the situation to help other people, and there can be a profound experience of well-being, inventiveness, and flexibility. In fact, the worst effects in the aftermath of disasters come when institutions try to impose top-down organization, as the military might. The presumption of mass chaos, looting, murders, rapes—this comes from something disaster scientists call “elite panic,” when people in positions of power fear the loss of their power and so overreact in violent ways. Solnit quotes the sociologist Kathleen Tierney’s description of the phenomenon:

fear of social disorder; fear of poor, minorities and immigrants; obsession with looting and property crime; willingness to resort to deadly force; and actions taken on the basis of rumor.

Elite panic on behalf of white conservatives led to a vast increase in prepping during Barack Obama’s presidency; there was a downtick in interest after Donald Trump entered the White House—ironic, given the comparative risks of a catastrophic event then and now. Trump has made the Environmental Protection Agency into an auctioneer of public lands, which has in turn rapidly undone commonsense regulation. Not to mention that with his deregulation and outright looting of the environment in the interest of privatizing public wealth, he has pushed the Doomsday Clock much closer to midnight. But survivalism, as it exists now in America, is not rational. It is emotional. It is the twisting of hypermasculine fear into a semblance of preparedness and rationality.

I lay in my hotel bed in Greenville, finally clean, and began to feel a strange and terrible sadness for the people I had left on the mountain. The majority of them had military backgrounds. I thought of how they had learned in the service to be powerful, effective, competent with weapons; I thought of their leaving the military and returning to a world where those virtues were far less valuable, even sometimes scorned. How strange it must be to go from the battlefield, always on high alert, capable of killing a fellow human, back to society, where people walked around nakedly vulnerable. Our support for veterans has never been strong, and it’s worsening rapidly. It must be alienating to feel devalued, to have to struggle to retain the kind of self-worth the military had built up in you, after you have given a great deal to your country. You start to believe that institutions have failed you. And so you begin to obsess over the end of society. You stock up on guns because you’ve been trained to believe that guns can protect you, and while you’re at it, you stock up on food and water and other things. You’ve become a prepper. You begin to imagine the end of society—which you see replicated so often in zombie films, television shows, disaster flicks, and dystopian literature that you can imagine it vividly—and perhaps you start to long for the apocalypse. It would solve so much of what makes you uncomfortable about the contemporary world.

“Liberals are going to be one of the first ones to die,” Rick Austin said when he was featured in a jokey, five-minute Daily Show segment about liberal preppers. “Maybe in the apocalypse, there won’t be conservatives and liberals, there will just be people that survive,” the correspondent, Desi Lydic, noted hopefully. Austin nodded and said, “Exactly. And dead liberals.” (Then again, he also said, “Hillary Clinton is running the largest crime syndicate in America.”) There had been so much bitterness and fury toward the left at Prepper Camp that I began to wonder now whether preppers were actually hungry for a time of upheaval so that they could finally watch liberals get their comeuppance.

But then I saw, to my horror, an uglier truth: that I was no better than my prepper brethren. And that because of my hypocrisy, I was probably even worse.

Perhaps doomsday libertarians do secretly long for a chance to rid the earth of people who threaten their supremacy; but there is something equally anarchic in me that longs for society to break so that we can rebuild it to be kinder, more generous, more equitable. Deep down, perhaps I am a prepper because I believe that the only way we are going to pry the world’s wealth out of the greedy, grasping hands of the billionaires who are willfully killing the environment is through a total collapse of the status quo. Perhaps I am a prepper because I have had enough: I am goddamn ready for the guillotines.

Maybe on both sides this secret death wish is born of an error, the conflation of society and the social fabric, which are in fact separate phenomena: society is made of the institutions that work together to ease human life; the social fabric is the beautiful anarchic bedrock of community and goodwill between human strangers. It is true that society is in deep trouble, but the social fabric is innate and strong, and this should be taken into consideration when preparing for a possible disaster. I was making the same mistake as people who had a vision of the world turned 180 degrees from my own. I was discounting the social fabric. All along, I had been making my survival preparations in a state of isolated intellectualization. I didn’t trust myself to make a pathetic little fire in front of other humans who knew how to do so better than I did. Faced with preppers who didn’t look or talk like me, I had become suspicious and afraid. My survivalism before Prepper Camp was revealed to be a paltry thing; it did not come from a community or out of a larger collective effort.

Maybe on both sides this secret death wish is born of an error, the conflation of society and the social fabric, which are in fact separate phenomena: society is made of the institutions that work together to ease human life; the social fabric is the beautiful anarchic bedrock of community and goodwill between human strangers. It is true that society is in deep trouble, but the social fabric is innate and strong, and this should be taken into consideration when preparing for a possible disaster. I was making the same mistake as people who had a vision of the world turned 180 degrees from my own. I was discounting the social fabric. All along, I had been making my survival preparations in a state of isolated intellectualization. I didn’t trust myself to make a pathetic little fire in front of other humans who knew how to do so better than I did. Faced with preppers who didn’t look or talk like me, I had become suspicious and afraid. My survivalism before Prepper Camp was revealed to be a paltry thing; it did not come from a community or out of a larger collective effort.

In the months after Prepper Camp, I have come to believe that liberals need to begin preparing in earnest for disaster situations. Libertarians and radical conservatives seem to own disaster preparedness, but liberals and progressives, equally made of tender, breakable flesh and bone, are just as much subject to the whims of nature. We need to use our knowledge, to apply to disaster preparations an understanding of science and fact; we need to develop real and actionable survivalism so that regular people can be as useful as possible in catastrophic situations. Everyday citizens should be taking classes in emergency health care. They should learn to store food and forage and make shelters. Every household should have stocks of food that will last for at least two weeks, the means to find water, an escape plan, a bug-out bag.

Individual action is good. Even better would be to counter individual self-obsession, to override the pervasive libertarian impulse to concentrate solely on the needs and desires of the self. Americans need to wake up to the necessity of immediate, powerful collective action. Self-reliance works only in stable civilizations, in which angry individualists like those I met at Prepper Camp have the leisure to concentrate on their own needs, to pretend that the concerns of the larger world simply don’t exist. I am here to tell you that we absolutely need the right-wing preppers’ decades of deep thought, their anxieties transformed into the everyday mastery of survival. Beyond learning from their mastery, we need to find a way to pull the loudest, angriest, most militant individualists into the collective, to make them understand the necessity of the common good.

We have pushed ourselves beyond the point in the human narrative when we can worry only about ourselves. We have fucked ourselves into a massive die-off, killing half the world’s species. California is on fire, Australia is on fire; we are already suffering, with displaced populations and major failures to the electrical grid. Doomsday is here now. We need to act collectively, we need to act fast, if all humans—libertarian or progressive or the hapless masses of the unprepared—are going to have a chance to survive this warming world.