The cast and crew of Mon Oncle watch Jacques Tati as M. Hulot, who is about to stumble into a fountain © Specta Films CEPEC–Les Films de Mon Oncle. From The Definitive Jacques Tati, which was published last year by Taschen

Discussed in this essay:

The Definitive Jacques Tati, edited by Alison Castle. Taschen. 1,136 pages. $225.

On the stage of a Swedish music hall, a sixty-four-year-old man in an elegantly cut brown riding costume, with top hat and white gloves, leads an invisible horse by an invisible bridle. As the animal tugs him behind a partition and he bounds up to mount, we catch sight of the horseman’s left leg. He reemerges and rides in circuits around the stage. But now the man has become both horse and rider, eyes alert and arms working the reins with formidable discipline while his legs—only now do we take in how very long they are—execute the high prancing movements and sliding turns of a dressage display. The performer’s age melts away in the spectacle and the perfect control that makes it possible, right up to the moment when he makes his exit. Once offstage, he passes out from exhaustion.

This was Jacques Tati in 1973, in a scene from his final film, Parade, an homage to the circus and music-hall traditions that had nourished him. It was the only time this particular routine, which he had performed at least since the 1930s, was ever recorded. The novelist Colette, when she caught his act in 1936, acclaimed him as “horse and rider conjoined . . . the living image of that legendary creature, the centaur.” At the time, Tati was just becoming known beyond the small revues and cabarets where he had developed the series of “sporting impressions” that spurred her to such unstinting praise: “Without any props, he conjures up his accessories and his partners. He has the suggestive power of all great artists.”

For the rest of that decade, by now a headlining act, he would tour Europe, from London to Berlin to Stockholm, as a much-appreciated mime and gag comedian. Yet he would not be much remembered if he had not, during the same period, tried his hand as a movie actor. It was on film that the artistry apparent to Colette would find its full and singularly original expression. In the six features he made between 1949 and 1974—Jour de fête, Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, Mon Oncle, PlayTime, Trafic, and Parade—he constructed a world apart, with its own forms, language, and humor, a humor as mysterious as it is funny. Unlike those of the silent comedies he adored, his gags don’t build toward climactic guffaws. Instead they pop up unexpectedly, as when two men, each carrying a furled umbrella strapped to a piece of luggage, rush past each other to board a bus at opposite ends. As their paths cross, the handles latch together and the umbrellas are left neatly linked on the pavement, while their owners continue on their way unaware. The trick takes a fraction of a second and has no connection to anything else that happens.

Tati’s first three features were received in their day as effervescent entertainments, and the unfailingly polite, blissfully oblivious M. Hulot—the out-of-sync onlooker with his pipe, closed umbrella, striped socks, and wrinkled raincoat—became an international comic icon. Tati picked up an Oscar for Mon Oncle, in which Hulot wandered in sweet-natured confusion amid a new world of ostentatious gadgetry and garish, eye-popping modernism. Fending off Hollywood offers, Tati enjoyed a happy combination of commercial success and critical admiration. However, his ambitious follow-up—the 70-mm PlayTime, for whose set he built something like a city (journalists called it “Tativille”) on the outskirts of Paris—proved a failure so devastating that he lost most of his personal assets, including the rights to his films. His last two productions were low-budget and not widely seen on release but continue to find devotees. In failing health, he was unable to realize his final screenplay, Confusion, in which he was determined to kill off Hulot and depict a video-dominated future without windows, where people communicate solely by screen.

At the time of his death, in 1982, he may have seemed a marginal figure to some—and indeed, with his insistence on his own laborious methods and his rejection of the norms of storytelling, he always positioned himself at the margins of cinematic convention. (“Every film presents a well-made, well-told story,” he told an interviewer in 1953. “Couldn’t we manage without one, just this once?”) He often claimed that his method was simply to keep his eyes open—on the street, in cafés, in shops, in stadiums—and notice how people actually behaved. He preferred nonprofessional actors in whom he detected humorous qualities, which he would tease out and teach them to express in more stylized form—what might be called a conflation of neorealism and Kabuki. (“What I’ve tried to demonstrate . . . is that, basically, everyone is amusing.”) His eye for the tiniest revelations of gait and gesture was matched by the architectural imagination with which he built the worlds his bewildered characters wandered in, a process that blossomed in the modernist residence in Mon Oncle—with its serpentine garden paths, furnishings in primary colors, windows like staring eyes, and absurd fountain in the form of a giant spouting fish—and then surpassed itself with PlayTime’s labyrinthine Tativille.

In PlayTime above all, he found a way to fuse the hilarious and the beautifully strange into a singular twentieth-century masterpiece, “a film,” in Francois Truffaut’s formulation, “from another planet, where films are made differently.” The metaphor could not be more apt. Released in 1967, PlayTime is as much a futurist epic as Kubrick’s 2001, except that the alien planet it explores is our own. Tati’s international travels had given him a vision of an encroaching homogenization, in which local character and tradition would inevitably be paved over and replaced by a vast, indistinguishable shopping mall. Jour de fête had been rich with images and sounds of horses, dogs, chickens, and insects. In PlayTime, the only animal presences are an unseen pet in a carrier at the airport—and a mysterious, impossible cockcrow at dawn in the heart of the denaturized city.

A suitable monument to Tati’s lifework can be found in Taschen’s five-volume set of books The Definitive Jacques Tati, a superabundant compendium, edited by Alison Castle, that is almost heavy enough to require a forklift. Taschen provides all the supplementation to the films that one might ever need; the films themselves can be conveniently explored in full in the Criterion Collection’s splendid seven-disc box set The Complete Jacques Tati. The Taschen set incorporates Tati’s writings and interviews; the screenplays for each of his films (including two that were never made); hundreds of stills, production photos, drawings, and blueprints; illuminating essays on various formal aspects of his work; and a detailed chronology of his life.

The stills alone—in a separate, wordless volume allowing the arc of each film to be revisited through carefully chosen images—make a powerful case for him as visual inventor. The essays establish the equal importance of his radical experiments in sound and his treatment of dialogue—or, more precisely, his transmutation of dialogue into a multilingual, semi-comprehensible musique concrète. Tati shot all his films silent, then typically spent as much time on the post-synced soundtrack as on the cinematography, although Tati’s notion of synchronization is not like anyone else’s. In nearly abstract soundscapes, every aural texture is deliberately placed, often in a way calculated to mislead and surprise. The young girl’s footsteps represented by the sound of Ping-Pong balls in Mon Oncle is one example out of a thousand.

The level of detail throughout Taschen’s set is staggering—appropriate for a filmmaker who considered no component minor. Tati conducted some six hundred auditions for the relatively small cast of Mon Oncle, collected recordings of 365 different samples of ocean waves for the beach scenes of Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, and by his own account personally mimed each extra’s movements for the crowded ensemble scenes of PlayTime. The screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière once described Tati at work in a recording studio: Carrière watched “with astonishment as he broke glasses, one after the other, for hours, with utmost seriousness, in order to obtain the best possible sound.” The long list of sound sources for Mon Oncle provided here includes “a double bass, a large rusty hinge, and an over-inflated beach ball.”

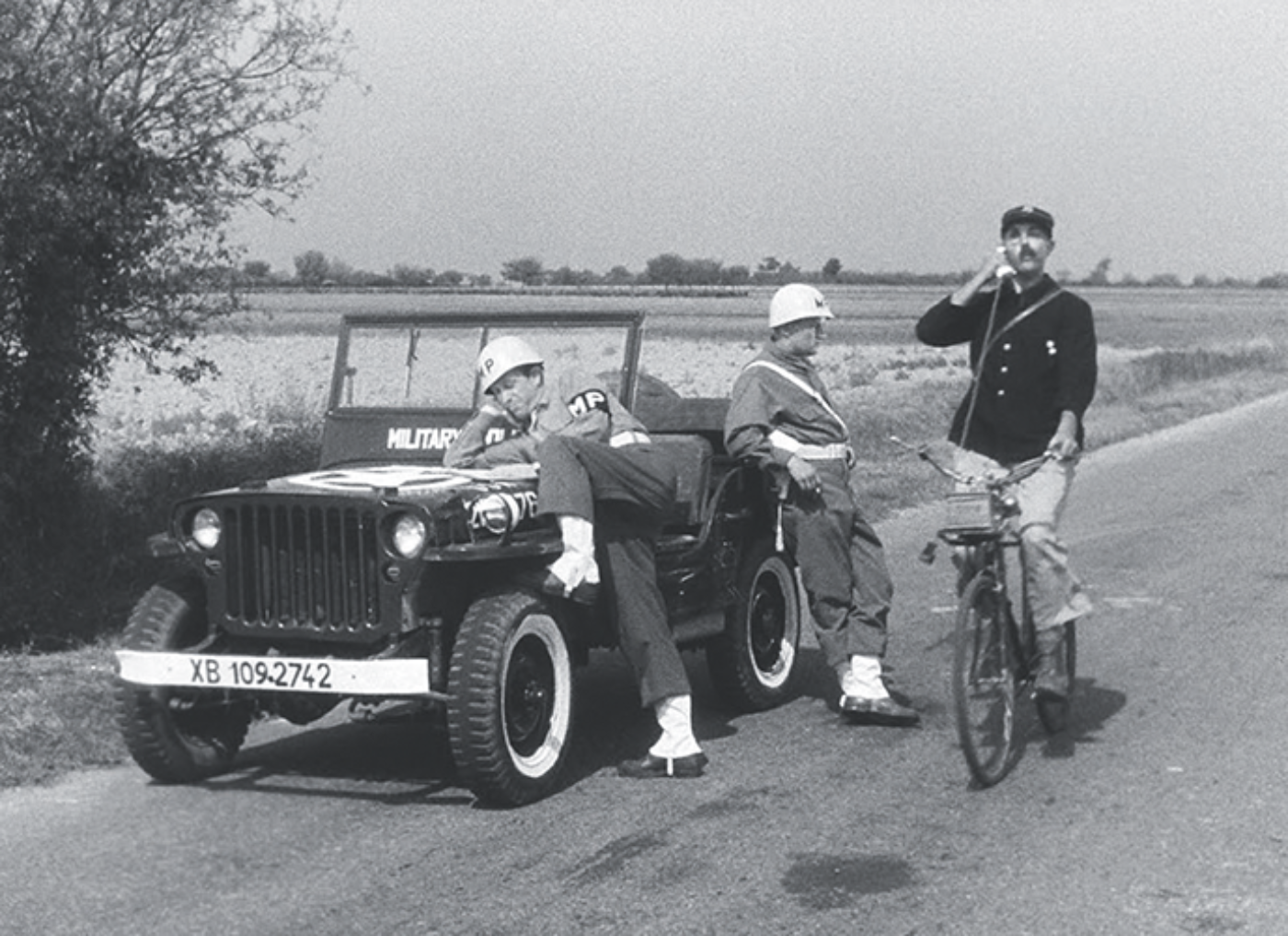

The finishing touch is a three-page inventory, in what looks like six-point type, of every motor vehicle appearing in a Tati film—from the 1914 Unic M1 pickup in the 1935 short Gai dimanche to the 1976 Volkswagen Scirocco coupe in the unfinished documentary Forza Bastia—along with an illustrated essay exploring the countless comic devices Tati extracted from cars and roadways. (A supreme example of this is the multicar pileup in Trafic, choreographed like a mechanical ballet and culminating not in disaster but in what looks like the idyllic liberation of the drivers from their vehicles.) This may sound like pedantry, but for anyone who has waded into Tati’s work it makes perfect sense. He himself couldn’t refrain from revisiting his films to tighten their editing, add or delete scenes, tweak the music or the color. Likewise, for a viewer who develops a taste for Tati, his films become not so much spectacles to watch as places to revisit, offering different sights and sounds each time.

Tati as a mime instructor in Evening Classes, a short film he wrote and starred in during post-production of PlayTime © Specta Films CEPEC–Les Films de Mon Oncle. From The Definitive Jacques Tati

How Tati came to be Tati is an enigma in itself. His family history was rooted in circumstances too bizarre not to recount, even if, as David Bellos acknowledges in his superb biography of Tati, evidence to support the details is elusive. It is a tale worthy of the most implausible nineteenth-century melodrama: a Russian nobleman, Count Dmitri Tatischeff (Tati’s paternal grandfather), serving as military attaché at the imperial embassy in Paris, has a son by his French lover; the count goes riding in the Bois de Boulogne and dies in a mysterious accident attributed by some to a nefarious conspiracy; the baby is kidnapped and taken to Russia to be raised by his father’s family; his desperate mother learns Russian, finds employment as a nanny in Moscow, and after seven years succeeds in abducting her child and bringing him back to France, to be raised in the well-to-do Parisian suburb of Le Pecq—where, to bring the story back to earth, he eventually marries the daughter of a prestigious Dutch picture framer and achieves a measure of prosperity running her family’s business. It is not hard to visualize this as one of the wildly plotted silent serials that Louis Feuillade was churning out when Tati was a boy.

The story, as Bellos notes, “has a mad and violent energy in utter contrast to the world of Jacques Tati’s films.” Anything resembling conspiracies, disguises, violent crimes, hidden motives, passionate love affairs, or dark family secrets is entirely missing from them. The characters have no backstories. We observe people talking, but what about is omitted as if it were beside the point. From the little we hear, it seems unlikely that anything they say could possibly be of any significance, any more than the background noise of public address systems, radio bulletins, or advertising pitches that intrudes from time to time. Tati might be conducting an experiment in showing what life is like when you take the explanations out and simply look at what is going on in the moment, as if through the eyes of an extraterrestrial visitor.

You could almost say that the past—history itself—is absent, except for its oblique entry through artifacts, clothing, buildings, vehicles, and technologies, so that we are led from the deep rural France of Jour de fête, where American culture penetrates in the form of a cowboy movie and a newsreel about high-speed mail delivery, to the globalized society of PlayTime, in which the metropolis has become something like a delocalized airport and all travel posters feature an image of the same International Style high-rise. For the inhabitants of Tati’s world, historical change is an environment into which they find themselves abruptly inserted without warning or explanation. His protagonists achieve true originality by their failure to connect with newly imposed guidelines and codes of conduct whose logic will always elude them.

The hapless and barely articulate postman Francois in Jour de fête, who misreads each clue and allows himself to be made the butt of every passing practical joker, becomes possessed—as he struggles to emulate the high-tech mail delivery he has seen on the movie screen—of improvisational genius, whether tucking a letter under a horse’s tail in lieu of a mail slot or turning a flatbed truck into an office for franking envelopes as he bicycles behind it. Tati’s running character, the perpetually hesitant M. Hulot—his face beaming goodwill to all, his long body hunched forward as if forever struggling to fit into the available space—unsettles every situation he intrudes on. With amiable if clueless politeness, Hulot reinvents the society he moves through by continually misinterpreting it. But, by Tati’s lights, that society—what he called “a right-angled world with arrows telling you where to go”—embodies, on an increasingly gigantic scale, a misinterpretation of human nature: “I don’t believe that geometrical lines bring out the best in people.”

Tati seems to have arrived at his art almost by accident. He was an indifferent student and showed little interest in entering the family framing business, although his apprenticeship certainly taught him a vast amount about pictorial technique. His father appears to have been a cold and demanding sort with whom Tati had trouble getting along. In typical visual shorthand, he would sum up their relationship in the memory of his father on furlough during World War I, standing on the beach during the family’s seaside holiday in full dress uniform: “It was as if a policeman had come to keep an eye on us. I often think of that.” Tati wasn’t one to let an image go to waste: years later he would plant a garrulous retired military officer at the resort hotel of Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday. Likewise, when at seventeen he came up with a mime routine to entertain fellow vacationers on the beach at Saint-Tropez—“Soccer from the Goalie’s Point of View”—he hung on to it as a component of his repertoire (the earliest, in fact) to be continually honed throughout his career. The final version can be seen in Parade, fifty years after he first improvised it.

He was affected by the worlds of sports, cabaret, and cinema. His admiration for Buster Keaton—the person he most wanted to meet when he came to Hollywood in the 1950s—was deep and abiding, and the complex gags of Keaton films such as One Week (1920), with its discombobulated prefab home, and The Electric House (1922), with its array of malfunctioning gadgets, can be felt like ancestral presences in the streamlined worlds of Mon Oncle and PlayTime. Above all Tati drew on what was around him. He won a Charleston competition at a seaside casino; staged elaborate pranks during his evidently enjoyable year of military service in a cavalry regiment during the late 1920s; and, when he pursued his passion for rugby by joining the Racing Club de France, made himself an indispensable member of the team with his mimed recaps of their matches.

It was in the annual Racing Club revues that he crossed the line into a professional career as a performer. It seems almost too casual a beginning to reconcile with the perfectionist who would insist on controlling every aspect of his films and who would be willing to stake everything on doing things his own way. He did not so much invent as discover himself, with a surprise that never quite wore off. The self-discovery was the fruit of leisure, of games and parties and practical jokes, of the things people do when there is no policeman on the beach maintaining surveillance. As has often been noted, Tati’s titles explicitly invoke fête and holiday and play and parade. Yet, full of fun as they are, no one would call his films madcap or zany or rollicking. The fun is of a more detached, almost ritualistic character. It has a curious quietness even as people are falling into rivers, setting off a stockpile of fireworks, smashing crockery, or attempting to enjoy dinner while the roof is falling in. If M. Hulot is not very good at keeping an eye on things, Tati is always there keeping an eye on him and everyone else, including most especially the ones who make it their job to stand watch like some sort of policeman.

Gregarious as he was, Tati also had the self-protective wariness of the autodidact, and perhaps also of the son enduring his father’s disapproving gaze as he walked away from the family business to become, as his father put it, “a clown.” As much as he savored the collective warmth of shared laughter, it’s the tincture of solitariness that gives his films their edge. The way he mutes and diffuses the speech of his characters feels like the expression of someone hovering at the edge of other people’s conversations, connecting with them only in sporadic fragments, as if across an invisible barrier. As his closest collaborator, Jacques Lagrange (the painter Tati credited as his “artistic adviser”), summed it up: “He was shy . . . He could never express himself. It was the story of his life. That’s why he was a mime!”

Still from PlayTime

PlayTime might be described as the work of someone who could only communicate as fully as he wished by building a scale model of the world and populating it with hordes of people, among whom Tati (as M. Hulot) would often be only another face in the crowd. To say what the film is about would be to take inventory—a daunting task—of the myriad microscopic events that occur between a point of arrival and a point of departure. Various people (businessmen, American tourists, nuns, visiting dignitaries, schoolchildren, press photographers, jazz musicians, M. Hulot, and a number of Hulot look-alikes who are continually mistaken for him) arrive in a Paris consisting of an airport; a maze of office buildings hosting an international trade exhibit; an apartment block replete with picture windows and television sets; a gleaming, American-style drugstore; and a cavernous upscale restaurant whose catastrophic opening night takes up about half the movie. It is a long day and a longer night, and in the morning everyone goes back to the airport, having seen nothing of the city’s famous attractions beyond a few fleeting, distant reflections.

This is not a story to be followed, even for its characters. It is a space to be entered, a space as broadly encompassing as the 70-mm screen whose first image is nothing but clouds so absorbing that you could look at them forever. And then you are in an enormous interior where gradually you become aware of the couple sitting on a bench, the wife murmuring affectionate trivialities as she says goodbye to her husband, the janitor sweeping the floor with a watchful eye for anything needing his attention, the man in white pushing a cart loaded with glasses and carafes, the military officer (but of what nation?) in full dress uniform, the woman seen from behind as she pushes a wheelchair (or is it a baggage cart?), the white-capped maid (or is it a nurse?) carrying an armful of clean towels, more and more people looking anxiously for where they’re supposed to go or dashing by in the background in front of a wide picture window. It’s a waiting room—its surfaces have a hygienic gleam; you might take it for a hospital. Multiple languages are being spoken. It’s an airport, after all—Orly as reconstructed by Tati, the gateway to an apparently seamless continuum of sterilized modernity where an American tourist can cheerfully announce: “I feel at home anywhere I go.”

If you are watching the movie the way Tati intends, you will become one more arrival, one more customer gawking happily at the display counters or looking for the right corridor or dutifully following the tour guide as you board the shuttle bus to the Hôtel Moderne. There are, as it turns out, so many ways to go astray, to follow the wrong arrows or (like Hulot) step into an interesting little alcove to find that it’s an elevator taking you to an unknown floor. At each moment you are obliged to look around and try to figure out what is going on, especially because so many different things are happening in the various corners of this flowing, interconnected, constantly deceptive space. You pursue a distant figure who is a reflection of someone behind you, you bang your nose against an invisible glass window, you dart in and out of a warren of workplace cubicles, you are swept along to view newfangled marvels like a self-operating vacuum cleaner and a noiseless door designed to be slammed in silence. You could be anyone. Each frame is a swarm of potential viewpoints. PlayTime can be watched the way a child looks at a favorite picture book—Where’s Waldo?, perhaps—not so much reading as inhabiting it, going back to every page until each element, each possible perspective, has been savored in a state of constant delighted astonishment.

There is an eddying continuity about all of this, but also—despite the murmurs and footsteps and electronic beeps, the exact resonance of a hand rapping on a glass door and the peculiar whoosh of that door as it closes, the sound of air leaking out of a leather office chair—the sense of a weird silence at the heart of this homogenized city of the future. It isn’t malevolent like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis or Godard’s Alphaville, but merely indifferent. Yet it is beautiful, its vistas of gleaming transparency imparting a kind of awe. Tati can hardly be against modernist design, whether of automobiles or homes or glass-walled office buildings, considering what stunning use he makes of it in every shot. It’s only what becomes of human life within those spaces that is terrifying to contemplate: except that terror, with Tati, translates instantly into comedy.

Finally, he brings all his characters to the luxurious, newly opened Royal Garden restaurant. As it happens, the restaurant isn’t quite finished yet: the workmen are still hammering away at crucial fittings, the management is getting edgy, the staff isn’t up to speed, and the architecture itself turns out to have major design flaws. Small quarrels and rebellions break out. As the guests begin to stream in, a slow process of dissolution has already begun. One of Tati’s early routines was “the clumsy waiter,” an act he would perform in restaurants for unwitting customers. The Royal Garden sequence expands that notion of decorum disturbed to a level of chaos that has its own kind of stateliness. The world falls apart slowly and grandly, and amid the wreckage a different one emerges as a free-spending American tourist whips up a drunken song-filled party. It is a sequence that suspends time. You hardly notice that half the film has gone by. When dawn comes, it feels as if the spectator too has been up all night.

For all that the making of it cost him, Tati had no regrets about PlayTime. He knew he had made precisely the film he wanted to make: a film that would in some sense merge with life. There is no end title, and he did not want the curtains to be drawn after screenings. His favorite critical response came from a fourteen-year-old who wrote to him: “What I really liked was that, at the end of the film, when I was back in the street, the film was still going on.” After multiple viewings, I continue to have such moments of recognition. On a family visit, I hear a voice from an upstairs bedroom: it is the self-operating vacuum cleaner announcing that it has completed its rounds. Straying into the Oculus of the World Trade Center, I reencounter the epic chilliness of PlayTime’s concourses. At the renovated LaGuardia Airport (still, like the Royal Garden, very much under construction), as I grope my way among newly instituted systems of ordering and paying for and picking up a cup of coffee, weaving past posters of the Airport of the Future that does not quite exist yet and racks of self-help books with titles like How to Be a Persuasive Manager, I begin unavoidably to feel as if possessed by the diffident ghost of M. Hulot.