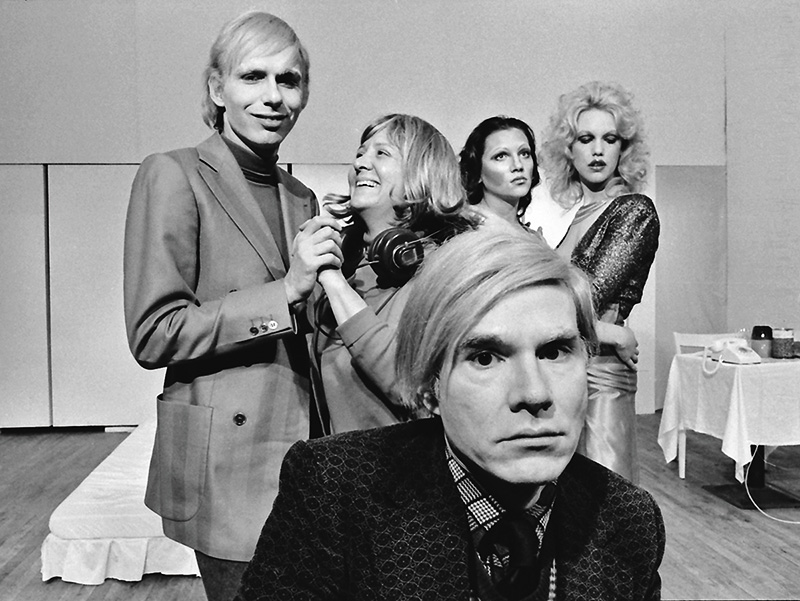

A Polaroid of Andy Warhol from the series Family Album, 1973 © 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society, New York City/DACS, London/Bridgeman Images

Discussed in this essay:

Warhol, by Blake Gopnik. Ecco. 976 pages. $45.

One thing I miss is the time when America had big dreams about the future. Now it seems like nobody has big hopes for the future. We all seem to think that it’s going to be just like it is now, only worse.

—Andy Warhol, America

It’s sort of my philosophy—looking for the nothingness. The nothingness is taking over the planet.

—The Andy Warhol Diaries

From time to time, Andy Warhol entertained the wish to host a television show called Nothing Special, and to operate a chain of cafeterias for solitary diners, the Andy-Mat. A social oddity since his Dickensian childhood, Warhol retained the imprint of not-having and not-belonging into adulthood, acquiring vivid people he didn’t much care about and pricey objects he never looked at. To a society poised to reject him, he presented a façade of detachment from other people’s lives, even from his own: in an interview with Alfred Hitchcock, he said that getting shot had been “like watching TV.”

What everybody knows about Warhol: He grew up in the Thirties and Forties in a cloacal, polyglot slough of Pittsburgh. He later said it was the worst place he had ever been. As soon as he could form the wish to get away, he set about doing so. It was no place for a gifted child, much less a gifted boy attracted to other boys. Warhol’s talent manifested itself at an early age; in school, his ability to draw helped deflect potential bullying. He was picked on, a bit. He acted girlish. He was sickly. After an attack of St. Vitus’ dance, a neurological disorder, his hands shook and his skin lost its pigmentation. His face always vexed him. In the Fifties he got a nose job, to no improving effect. It’s unclear when he first recognized his homosexuality. During his childhood, and for decades afterward, being queer was unspeakable in America. One way to glide past a boy’s effeminacy was to call him “artistic.” Warhol’s talent got him accepted at Carnegie Tech, where he enjoyed a reputation as an “eccentric.” After graduating, he moved to New York. With unusual rapidity he became a prominent commercial illustrator. At an epochal moment in the early Sixties, he painted a Coke bottle. The rest is history.

Warhol’s life story gets recounted a lot, providing as it does a slightly skewed, Horatio Alger–ish, rags-to-riches uplift: the infrequently true story America likes to tell about hard work paying off, success in the land of opportunity. It also bears a resemblance to those fairy tales in which the happy ending doesn’t quite pan out, even when magical events transpire. Granted three wishes, the old woman finds herself with a permanent sausage on her nose. Warhol wanted to be rich and famous more than he wanted to breathe; in hardly any time at all, his wish was granted. But however avidly the world treated him like an enchanted princess, his mirror showed him an ugly duckling. The only unusual aspect of this story is that Warhol had already seen it in a movie a million times.

He craved the company of others, but never knew what to do with them. In the Sixties, when he gave up painting, he put them in his movies, but the films only enhanced his separation. Their presence dramatized his absence, their logorrhea his silence. In Bob Colacello’s Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up, which chronicles the Warhol Seventies and Eighties, Warhol often appears forlornly isolated in rooms full of ostensible friends, clutching a tape recorder or camera like a magic wand, as if turning life into the memory of life without having to experience it. Colacello also notes that however often people hosted Warhol in their homes, they were never invited into his own beautifully appointed town house. On the rare occasion when he had to let someone in, Warhol grew nervous and brusquely impatient for them to leave. Minutes after they left, he called them on the telephone.

Andy Warhol with the cast of his play Pork, onstage at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, New York City, 1971 © Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

Warhol was seemingly incapable of spontaneity, some private calculus forever ticking away in his head at a speed different from that of normal cogitation. He had a Zen-like receptiveness that enabled him to stare for hours at faces, objects, or empty space. Warhol’s art is about time, and death, and perceptual slippages; he heard the terrifying static of existence, and operated in a mental space that usually precluded ordinary human interaction. His passivity was grandly open and indifferent to interpretation. His personality was constructed to draw people close but keep them at a distance. He had a horror of being touched, an even deeper horror of emotional involvement. He needed buffers and screens between himself and the world, and in that regard his life was eerily prophetic of a time when screens would feel more real than reality. A maestro of ironic knowingness, he declared himself unknowable: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” No one, thus far, has excavated anything surprisingly at odds with the Warhol reflected in his work or in the books he published. Everyone is less and more than their publicity, and much of Warhol’s life, like everybody’s, has the prosaic quality of nothing special. It doesn’t detract from his art to observe that Warhol had no imagination whatsoever. His literal-mindedness was his strong suit.

Warhol’s loneliness seeps through accounts of his life. Although he treated longing and disappointment as diminishing flaws, to be met with a stoic “so what,” he was alone, needy, insecure. He was dead certain about his ambitions, however, prepared to walk over corpses to get where he wanted to go. His unwavering trajectory cost him dearly in the way of Freud’s “ordinary unhappiness.” This is not an unusual feature of a famous artist’s biography. Egotism, ruthlessness, and manipulation are standard requirements for the pitch of global fame Warhol finally reached. The novelty, in his case, was the wonderful simplicity of his approach. His weaknesses were his weapons. He trained his work on what he liked best, the tawdry pathos of supermarkets and tabloids, Coca-Cola and plane crashes, the very realm of homely kitsch that art was thought to ignore and rise above. He played up his gayness in the Cedar Tavern and the White Horse Tavern, saloons where boozy Abstract Expressionists brawled over the size of their spiritual innards. Warhol dislodged a culture of heroic interiority with the freaky, externalized clarity of amphetamine, making America safe for the fey, the ironic, the obdurately matter-of-fact. When a radio host concluded an interview by thanking “Mr. Andy Warhol,” the testily silent artist grabbed the microphone and said, “That’s Miss Andy Warhol.”

His self-deprecation was a charming pose, but his diaries suggest that he really did think himself an incurable mess, sartorially wrong, his wig crooked, his skin a relief map of rashes and zits. He found his sole escape from everyday anxieties in constant work.

He never expressed a jot of self-importance. He genially agreed when critics said his films and paintings were garbage. He neutralized hostility by refusing to defend or explain himself. Most saliently, he never paused in his production of objects, which appeared in such fantastic profusion that they’re still being catalogued thirty years after his death. The staggering volume of Warhol’s output and cannily preserved residua confounds any notional scheme of valuation.

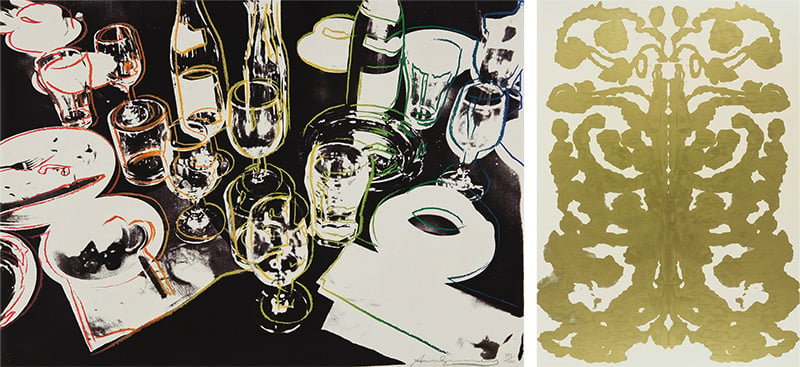

Left: After the Party, 1979, by Andy Warhol. Courtesy Phillips; Right: Rorschach, 1984, by Andy Warhol © The Museum of Modern Art/SCALA/Art Resource, New York City. Both © 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society, New York City

The critic Dave Hickey once remarked that Warhol had no idea of middle-class life, and that sounds exactly right. We associate Warhol with both the bottom and top of the New York food chain, seldom anywhere between. One ponderous feature of “the Warhol Sixties” is the phenomenon of the Warhol superstar—Fran Lebowitz called it a private joke that got into the water supply. Some people came to believe that holding his attention for a time meant that his interest ran deeper than their entertainment value. It didn’t. As Colacello makes risibly clear in Holy Terror, Warhol’s interest in other people consisted chiefly in what they could do for him, not the other way around. (“What is interesting to me,” Paul Valéry wrote, “is not always what is important to me.”) Warhol discarded people he had no further use for, often through expert applications of gaslighting. This wasn’t the case with Valerie Solanas, however, who claimed after shooting him that Warhol “had too much control” over her life. The opposite was true. Warhol declined to have any control over her life. She wasn’t superstar material. As someone once said about Adolf Hitler: some people aren’t equipped to deal with disappointment.

The unimaginable fame and wealth Warhol acquired was never enough: there was always somebody richer, more famous, or prettier, in whose proximity he felt inadequate. Abjection was his métier, and it was an integral part of his charisma. As in timeworn film scenarios, the more famous he became, the emptier he felt. “I knew Andy for twelve years,” Warhol’s longtime live-in boyfriend Jed Johnson told the biographer Victor Bockris. “He never talked about anything personal to me ever.” Warhol’s attempts at intimacy were few, forever ending in regret, doomed by his choice of impossible love objects and a gross misapprehension of what intimacy involves, i.e., relinquishing control. The sickly child who cherished Shirley Temple and fan magazines had a lifelong obsession with Hollywood clichés. “I’ve been hurt too many times,” he often said, like a Fifties movie queen, by “falling in love.”

A ridiculous person in some key areas of life, you could say, a cross between Joan Crawford and Franklin Pangborn. Also a genius of withholding and apposite timing. At times, no doubt, an irritating creep. Everyone encountered the same Warhol, but each came away with a different notion of who he was. This could only be true of someone deliberately standing back from the passing circus, taking notes.

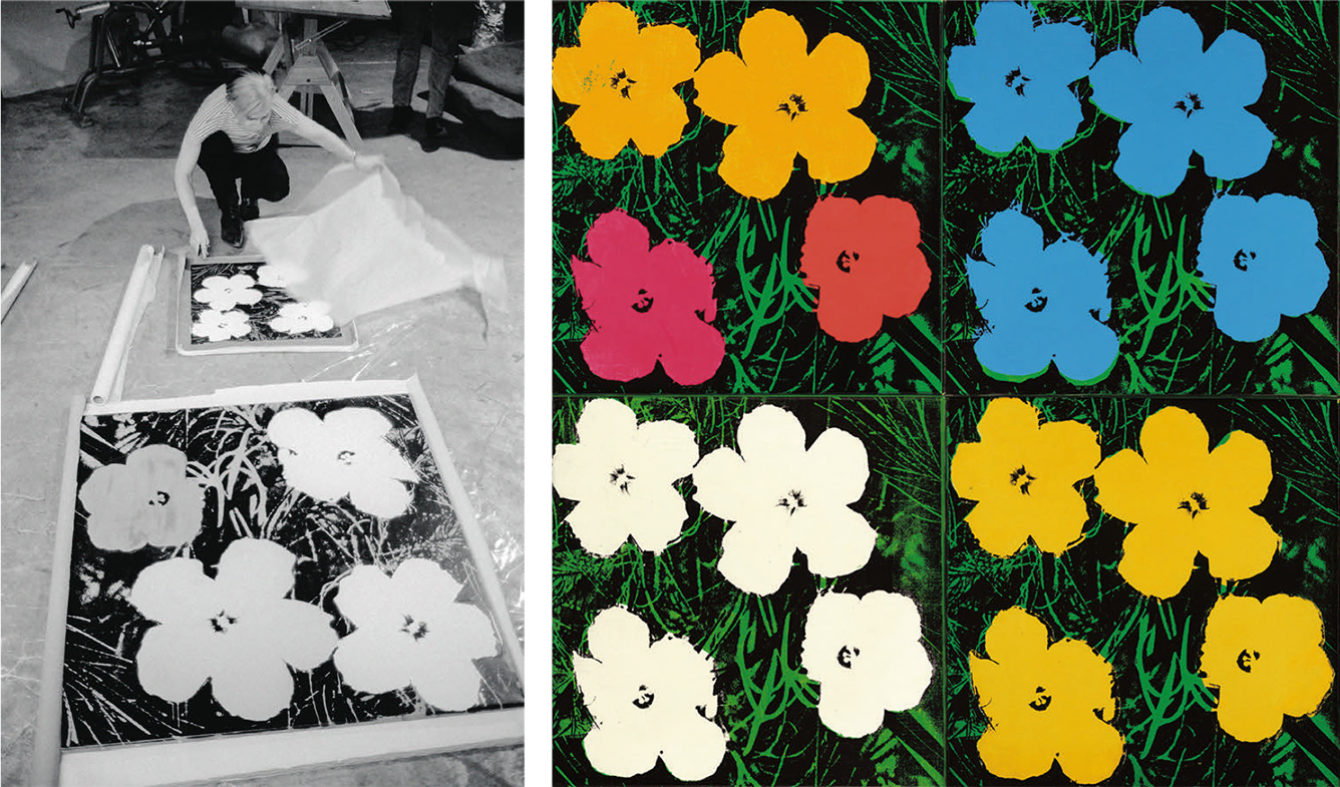

Left: “Andy Warhol,” by Stephen Shore, circa 1965–67 © The artist. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York City; Right: Flowers, 1964, by Andy Warhol © 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society, New York City/DACS, London/Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images

Writing about Warhol poses inherent difficulties. A fulsome literature already exists: the very thorough, very entertaining biographies by Bob Colacello and Victor Bockris; Wayne Koestenbaum’s brilliant book-length study, Andy Warhol; Jean Stein’s Edie; Mary Woronov’s Swimming Underground; and Viva’s Superstar—or, for total immersion, Warhol’s a, a novel that records twenty-four hours of amphetamine chatter among the 47th Street Factory’s semi-resident speed freaks. There are essays and catalogue texts that examine every aspect of Warhol’s life and art. The Silver Factory years, when Warhol conferred celebrity on otherwise unknown people in his ken, compel more attention than others: the superstars provided the exuberant “personality” that Warhol withheld, in a sense acting as surrogate Andys. After the Solanas shooting, Warhol gradually restricted his social life to the rich, the already famous, and his own employees. He became less interesting to the kinds of people he wanted to keep away from him anyway. His mordant sense of absurdity remained intact. The Andy Warhol Diaries cover every day of his last eleven years, and reveal more about his ability to cut through the grease of social relations than whole libraries of exegesis. Warhol kept his fingerprints off his work; even the posthumously published Diaries were dictated to Pat Hackett. This ghostliness invites all manner of interpretation, but Warhol contrived his work, and his public image, to be taken at face value. As his late Rorschach inkblot paintings made clear, what you find in his work is what you read into it. You don’t need an art degree to get it.

His ascent and eventual centrality appear foreordained in the post-Warhol cosmos—where Andy Warhol Pocket Planners, Andy Warhol Banana Tote Bags, Andy Warhol Philosophy Pencil Sets, and Andy Warhol’s Greatest Hits Sticky Notes are among myriad Andy Warhol provender available on Amazon—but Warhol’s success owed as much to chance and contingency as it did to brilliance and calculation. Warhol always needed collaborators to support the scale of his activity: to squeegee the silk screens, sit for his camera, perform in his movies, edit his magazine, hustle the portrait commissions, manage his business, sell the work, and so forth. The Warhol phenomenon had too many moving human parts to ascribe its effects solely to the artist’s psychology, or the artist’s will. The extreme tension in Warhol’s work between meaning and non-meaning has to do with random gestures, accidents, and visual noise carrying as much weight as design. Likewise, a lot that happened in Warhol’s life just sort of happened, the way lots of things happen in every life.

This obvious fact, and much else that would occur to most sentient beings, has entirely eluded Blake Gopnik, whose elephantine, ill-written, nearly insensible Warhol has now been unleashed, weighing in at nine hundred pages, any of which suggests nothing so much as an incredibly prolonged, masturbatory trance of graphomania. The book’s dedication purports that Matt Wrbican, the late archivist of the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, “wanted this book to be . . . longer.” If so, Wrbican definitely shared Warhol’s sense of humor.

A prodigy of research, Gopnik claims to have interviewed “more than 260 lovers, friends, colleagues and acquaintances of the artist” (261? 263?), and consulted “some 100,000 period documents.” None of this effort has produced anything resembling a fresh idea. Information that has been available for decades is rolled out as startling news, embedded in a dense lard of fatuous pedantry and vapid generalizations. Gopnik’s writing generally reads like boilerplate cribbed from bygone reviews and magazine articles, recast in a squirmy, sophomoric prose that deadens everything it touches.

Gopnik’s prelude features a graphic account of the five-hour surgery that saved Warhol’s life. “Stories have been told of three or four bullets piercing Warhol’s body . . . but Rossi found that a single slug had punched straight through the dying man.” It is by far the liveliest scene in Gopnik’s book, and it occurs in the first three pages. It also presages the author’s bizarre, recurring conviction that he has discovered something that no one previously imagined, or disproved some widely held, erroneous belief—invariably, something everybody knew, or something nobody believed.

In most instances, the alleged revelation is something nobody could possibly care about—that Warhol’s assistant Gerard Malanga, for example, misremembered which pop song was playing in Warhol’s studio on a particular date, or that Warhol was mistaken to think that Edie Sedgwick invented the miniskirt, because it “had broken out a few months earlier in both Paris and London.” Gopnik’s ideal reader is someone who has never read a word about Warhol or contemporary art, seen a movie, or formed two consecutive thoughts without assistance.

Taking a deep dive into Warhol’s childhood, Gopnik parses the family ethnicity at numbing length, citing a “world movement for Carpatho-Rusyn culture” only to chide this dubious movement for presuming to link Warhol’s art to “the Rusyns’ hand-painted Easter eggs,” whereas “one of Warhol’s more notable achievements was to push back against both signature touch and hand painting.” No statement escapes pointless qualification: “And while it’s true that there is a notable folk element in his early commercial art,” this is not “specifically Rusyn”—whatever that means—but rather “generic enough to have come out of almost any peasant culture.” “Folksy styles were everywhere in Warhol’s early years,” Gopnik adds with a sigh, “as has now been largely forgotten.”

No scrap of miscellaneous data escapes Gopnik’s scrutiny, or fails to trigger an avalanche of mindless verbiage. Everything that happens happens for portentous reasons, foretelling this or that, or recalling something from Warhol’s past, or maybe not—Gopnik can never decide, but he assumes anyone reading his book is a moron who needs the benefit of his guesses. Warhol would shrink to about twenty pages if he simply stated what happened and left it at that. Somewhere in the suet of Chapter 19, Warhol fails to give Malanga money for a taxi after their return from California:

There are a few explanations for Warhol’s froideur toward his assistant. There had been an incident at the motel in Venice Beach when Malanga had brought a girl home to their shared room and Warhol had exploded.

The refusal of cab fare may also have been Warhol making clear that, after all those weeks in close quarters, the young man who had been “helping out” was indeed an employee more than a friend. For the next quarter century, Warhol was forever trying to remind staff, and himself, of the distinction. They and he mostly managed to ignore it, which was a source of everlasting tension.

But the most likely explanation is that Warhol wanted to save the cab fare.

“Maybe,” “possibly,” “probably,” “might be,” and “precisely” operate in Gopnik’s prose like maypoles for ribbons of blather:

Malanga’s account . . . might be the source of the words put into the artist’s mouth seventeen years later.

But despite these complications, or maybe because of them.

Maybe he was predicting getting dumped once again, and the murderous bitterness he knew he’d feel.

Nonintervention was probably his greatest sin.

The role of the A-Men in Warhol’s life has probably been exaggerated, mostly for the sake of the bohemian patina they lend it. But that patina is precisely what Warhol was after.

As usual, Warhol had figured out precisely where he needed to be if he wanted to register as being on the cutting edge.

Maybe it was precisely that dual nature, suiting both matrons and mavens, that made the Flowers Warhol’s first serious salable wares.

What is new in Warhol is, on virtually every page, a species of trivia normally consigned to archives, for the simple reason that it is trivia, the submental detritus of liquor-store receipts and electric bills, occasionally helpful in fixing the date when something occurred; Gopnik is endlessly fascinated by this experiential lint, and can ruminate for pages on the possible meaning of a laundry ticket. Determined to find significance in any bit of minutia he comes across, he often achieves an almost sublime idiocy:

In 1961, Warhol’s own gum chewing might have been a new pose, but it reflected a genuine and lifelong interest in the worldview and culture of actual gum chewers.

He might have liked frankfurters fine, but earlier that day he’d asked a photographer to treat him to the newest and fanciest French restaurant in town.

But Warhol’s striped shirt also pointed to a more recent precedent with just as much cultural cred as Picasso.

There are deeper ponderings, too, gleaned no doubt from over 260 interviews:

Maybe the most important thing to recognize . . . is that he came across to his contemporaries as your standard secular, gay, lefty, party-going avant-gardist, and that was the image he chose to let loose on the world.

Gopnik’s admiration seems inspired entirely by Warhol’s fame and success. His praise sounds like contempt, couched in the vernacular of a high school newspaper circa 1959: “yet another of his zany conceits,” “as a good avant-gardist,” “with his brilliant eye for the avant-garde,” “a wacky avant-garde aesthetic,” “his goofy, impractical offer,” “his patina of weirdness,” “some weirdo artist,” “weird and wooly collaborations,” “the simple weirdness of that concept,” “his weirdness would always win out.”

There’s more. Much more. Unidentified quoted material appears, suspiciously often, in support of whatever nebulous point Gopnik thinks he’s making. Frequently, named persons are quoted without references, leaving an impression that Gopnik personally interviewed people who never spoke to him. Gopnik projects his own punitive fantasy of Warhol as a creature from outer space onto an assortment of straw figures—the public, the reader, the art establishment, or whomever—as stubborn “myths” only Gopnik has been brave enough to dispel: “so much for [Warhol] as a film ignoramus,” “Warhol often gets described as apolitical, which isn’t right,” “the myth that Warhol was close to teetotal falls under the weight of evidence,” “this fits with a common notion that Warhol was deeply un- or even anti-intellectual, and maybe marginally illiterate or at least dyslexic.”

It’s unlikely that anyone in America needs Gopnik’s lucubrations on amphetamines and their effects, though it may come as news to young people that many different kinds of pharmaceutical speed were easily available in the Sixties, all of them more fun than Adderall. To his credit, Gopnik does provide a lengthy description of the gay scene Warhol found in Pittsburgh during the Forties, though the best one can say is that he spoils this less than everything else. His fondness for anachronisms (“hardly conformed to the era’s stereotype of the wacky gay man,” “clichéd image of a slight and swish queer artiste,” “the light-loafered limp-wristedness,” “on the receiving end of his friends’ swishophobia,” “a brazen self-portrait by an unrepentant homosexual”), even when mobilized in defense of Warhol against “homophobia,” reflects the provincial squeamishness that provides the only real hilarity in this book. For a time, Warhol photographed men having sex in his studio; Gopnik refers to this as one of the artist’s “more scurrilous projects.” He pronounces the crotch shot Warhol did for the Rolling Stones’ album Sticky Fingers “naughty and daring.” Ondine, the Pope of Chelsea Girls, “supplied plenty of naughty gay talk.” This nervous, prudish flippancy, native to the suburban bourgeoisie, addresses a constituency Warhol had no use for whatsoever. The most telling example, in its way, is Gopnik’s description of Trash as a film “about the sexual escapades of a drug addict.” The entire premise of Trash is that the male lead doesn’t have any sexual escapades, because he can’t get it up.

This book could appear only at a time when the bohemian mobility, sexual freedom, and cultural ferment of New York in the Sixties, Seventies, and early Eighties are not simply being forgotten, as people who were there die off, but becoming unimaginable. A time when New York has become so cluelessly middle class that someone can actually write, of the back room at Max’s Kansas City, that Warhol “behaved more like the cool-cat senior in high school who the freshmen do everything to impress and who looks on with amused condescension.” This is the point of view of someone who never, ever could have gotten into Max’s.