A Cotton Office in New Orleans, by Edgar Degas. Courtesy Musée des Beaux-Arts, Pau, France

In 1873, while visiting family in America, Edgar Degas painted a scene from his uncle’s cotton brokerage in New Orleans. The artist’s only work to enter a museum collection in his lifetime, it bustles with commerce and clerical absorption. Men review ledgers and newspapers, or scrutinize sample tufts through wire-frame spectacles. A mustached figure scoops handfuls from a table heaped with cotton, as though disemboweling a cloud.

One hardly expects unassuming businessmen in nineteenth-century paintings to commit historic crimes. But among those depicted in Degas’s canvas is William Bell, future leader of the Crescent City White League, a militia that would later overthrow the Reconstruction government of Louisiana. His unlikely cameo features in Edward Ball’s Life of a Klansman (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $28), the captivating biography of a foot soldier in the White League. Its subject is the author’s great-grandfather, Polycarp Constant Lecorgne, whose life offers an intimate origin story of the white-supremacist movement.

“The Ku-klux are the boogeymen of American history,” Ball writes. (He uses the term as a catchall for contemporary militias.) “What if this band of guerrillas is fascinating and obscene because it is a scapegoat that we force to carry all of the antiblack energies of the wide, white society?” Seeking to unmask the society behind the scapegoat, Ball reconstructs his ancestor’s world and moral insight in a work of novelistic expansiveness.

Born in 1832, Constant, as he was known, grew up comfortably in New Orleans’s French Quarter, the son of a Breton naval deserter and a woman from an old Creole family of wealthy slaveholders, so-called grands blancs. You might call him a victim of “economic anxiety.” Picturing his decline from prosperous carpenter with a home and seven slaves to indebted renter on an all-black city block—with an undistinguished intermission in the Confederate Army—Ball makes it easy to grasp, if not excuse, the sense of social upheaval that motivated Klan violence. “Whites [felt] the great perversion,” Ball writes of Reconstruction, evoking their fury at formerly subservient black neighbors, who now started newspapers, smoked cigars on street corners, and strutted with rifles as enforcers of the federal occupation.

Gradually, white supremacists like Constant wrested control of Louisiana from the Reconstruction government. Led by militias such as the Ku Klux Klan, the White League, and the Knights of the White Camellia, they infiltrated police departments, electoral ward clubs, and volunteer fire companies, which proliferated amid rumors of a black conspiracy to destroy the city by arson. By 1866, this nascent “Ku-klux” was bold enough to attack the state’s constitutional convention at the Mechanics’ Institute in New Orleans. In broad daylight, they stabbed or shot to death nearly two hundred black supporters of multiracial democracy.

The perpetrators weren’t hooded renegades, but uniformed firemen and police officers, who used the city’s electric fire-warning bells to coordinate the killings. There was no need for anonymity; among the masterminds of the carnage were the city’s mayor and sheriff. It was only later, when the federal government responded with troops and the nation’s first antiterrorism laws, that Klansmen adopted their infamous, esoteric pageantry—a distraction, Ball argues, from the communities they belonged to and the future generations whose interests they advanced.

Ball refuses to “disown” the past, believing it crucial for white Americans to acknowledge that “marauders like Constant are our people, and they fight for us.” Accordingly, he approaches his ancestor’s story with shame, but also sympathy and imagination. He sees Constant as a boy in New Orleans, attracted and repulsed by the African drumming in Congo Square; as a disfavored younger son who bet his future on the fight for secession; as a man who clung to the lower rungs of the upper class with black labor, and then lost it. Where the record is silent, he substitutes the words of Constant’s contemporaries, or supplements the evidence with informed speculation; in a postscript, Ball cites the work of the scholar and writer Saidiya Hartman, who describes her own methods of coping with the archival lacunae of black history as “critical fabulation.” Ball constructs his own microhistory on a similar model, stitching and patching the fragments of a past obscured by the willful forgetting that James Baldwin termed “innocence.”

In two short interludes, Ball meets with descendants of those who survived the Mechanics’ Institute Massacre, letting their family stories share space with Constant’s. It’s a reprisal of Ball’s 1998 debut Slaves in the Family, in which he reconstructs the genealogies of African Americans whose ancestors were enslaved by his own. Here, the connections feel more tangential, and the encounters forced. Perhaps Ball could have investigated not Constant’s survivors but his successors, who, fearful of replacement by racial “inferiors,” are once again infiltrating police departments and organizing militias. Most readers will have little trouble drawing these parallels themselves; the strategies are familiar because the struggle is ongoing. White supremacy, as Ball describes it, is “a perennial mold in the national house.”

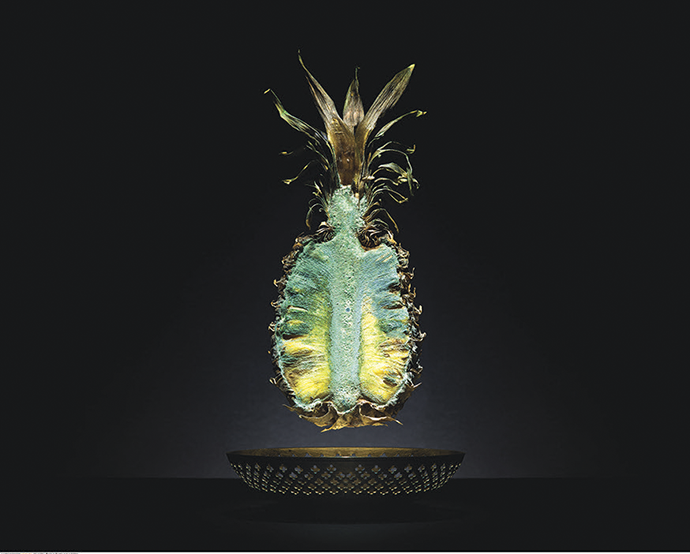

“Pineapple,” by Klaus Pichler © The artist. Courtesy Anzenberger Gallery, Vienna

Mold, for its part, deserves better associations. It was a “pretty golden mold” on a cantaloupe in Illinois that enabled the mass production of penicillin; more recently, fungi have proved useful in eliminating industrial waste—some digest cigarette butts and jet fuel—and as substitutes in plastic packaging, concrete, and leather. There are even efforts to create fungal houses, fungal computers, and fast-growing fungal military barracks, as well as to extract fungal antivirals that might stave off colony collapse disorder in bees. Even so, fungi are among the most neglected organisms on the tree (why not the toadstool?) of life—despite efforts by contemporary evangelists to spread what one refers to as “Liberation Mycology.”

Among these boosters is Merlin Sheldrake, a young British biologist whose debut book, Entangled Life (Random House, $28), is an exuberant introduction to the biology, ecology, climatology, and psychopharmacology of the earth’s “metabolic wizards.” Sheldrake mixes hard science with the story of his own “enlichenment.” He stews naked in rotting wood chips at a fermentation bath in California; psychically fuses with a mushroom during a study of creative breakthroughs and LSD; scours the forest floor with camouflaged truffle hunters in Italy; and crawls through Panamanian jungles searching for rare blue flowers in the genus Voyria, which, having lost the ability to photosynthesize, subsist entirely on the nourishing attention of underground fungal networks.

Sheldrake’s playful, wide-eyed register is occasionally trying, but it’s hard not to be astonished by the ways that fungi challenge the very idea of hard boundaries between beings. He describes fungi that digest wood on behalf of their symbiotic partners in huge climate-controlled mounds; fungi that hunt nematodes by counterfeiting their pheromones; and fungi that infest the bodies of “zombie” ants and wasps, puppeteering them on suicide missions of spore dispersal. The latter may function similarly to the way magic mushrooms operate on humans, raising ontological questions of which entity can be said to have a psychedelic experience. “Do psilocybin fungi wear our minds,” Sheldrake writes, “as Ophiocordyceps and Massospora wear insect bodies?”

These questions are most acute in the case of the so-called Wood Wide Web, the sprawling network of mycorrhizal fungi that sheathes plant roots and allows them to trade nutrients. The fungi extract minerals, such as phosphorus, for the plants, which in turn provide the fungi with energy from photosynthesis. Beyond this seemingly simple symbiosis is an entire range of mysterious network effects. Mycorrhizal fungi can facilitate the transmission of nutrients and chemical signals between plants, but biologists disagree over who, exactly, directs the exchange.

Do plants use fungi, with their root-like hyphae, as cables? Or are the fungi “brokers of entanglement able to mediate the interactions between plants”? Clarifying the relationship will require greater observation of underground processes than scientists now have the ability to conduct. Whatever its answer, the mystery is yet another demonstration that life, in Sheldrake’s words, is “nested biomes all the way down.”

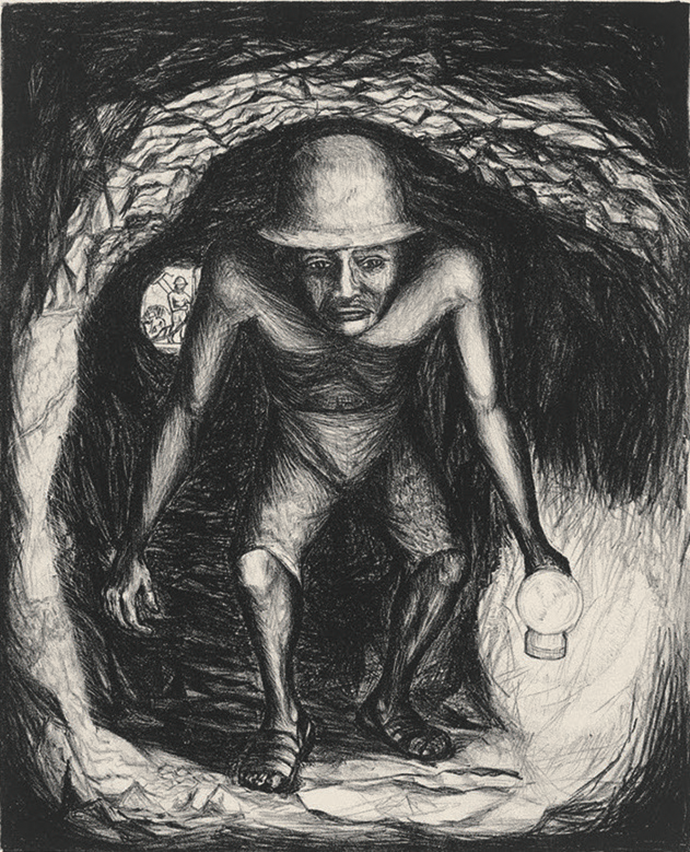

Silver Mine Worker, by Francisco Mora © 2020 Catlett Mora Family Trust/VAGA at Artists Rights Society, New York City/Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alvin S. Romansky/Bridgeman Images

Fungi are among nature’s best miners, skilled at tunneling through hillsides and turning stone into soil. Bioluminescent mushrooms once lit British coal tunnels, while an Australian fungus recently proved capable of detecting trace quantities of gold. Such marvels lend underground work a romantic aura, but its reality has more often been defined by horrific exploitation. In A Silent Fury (And Other Stories, $15.95), the Mexican novelist Yuri Herrera revisits one particularly macabre incident in 1920, a mine fire that killed more than eighty workers in the author’s hometown of Pachuca, in the central state of Hidalgo. Nobody can say what started the blaze, but less than an hour after it erupted, managers working for the United States Smelting, Refining, and Mining Company decided to seal the shafts. They intended to save the mine by suffocating the fire, conveniently concluding that anyone who hadn’t yet evacuated must have already died. Six days later, they discovered charred bodies clustered near the entrance—and, a few levels down, seven survivors.

Like Life of a Klansman, Herrera’s book is a microhistory inspired by an absence in the archives. But where Ball enriches the record with context and speculation, Herrera conducts a crisp, matter-of-fact investigation. In quietly seething prose—ably translated by Lisa Dillman—he parses the evasive accounts of contemporary journalists, judges, mine administrators, and civil authorities, noting the implications of each elision and discrepancy. By the end, the “accident” looks more like homicide, a crime quickly covered up by local officials and company bureaucrats who barely saw their workers as human.

The survivors sheltered from the smoke in a side tunnel two hundred meters below the surface, subsisting on a trickle of muddy water. After several days, a few ventured out; two climbed a ladder and suffocated in a pocket of gas. Others found leftover beans and the burnt-out remnants of a control station with a disconnected phone. Meanwhile, up above, their employers posed for pictures and scouted locations for a mass burial. “They look somber, circumspect, but not troubled; one of them is smoking a cigar,” Herrera writes. “It looks as though they’re very concerned about coming off in the official document like men who are undaunted, who never lose their grace despite being atop a burning grave.”

Journalists blamed the “naturally indolent” miners, many of whom were indigenous, for causing the disaster. The courts, meanwhile, allowed the management to “clean up” the mine before sending an inspector, and instructed their photographer to use “the greatest possible economy.” (He took only four pictures of the scene.) After “rescuing” the surviving miners, the company whisked them away to an in-house hospital, where doctors announced that they were “in a perfect state of health but starving to death.” Nobody bothered to ask them for a quote.

The company promised a monument to the deceased; it was never built. But there was a commemoration, of sorts. The “American community” donated a gazebo to a nearby park six months after the fire, dedicating it to the local government. Herrera argues that it was meant as a wink of gratitude for the cover-up. The book is a gripping demonstration of how much can be unearthed from the omissions of official accounts. “Silence is not the absence of history,” Herrera writes. “It’s a history hidden beneath shapes that must be deciphered.”

Fly Agaric Cluster, by Patrick Jacobs © The artist. Courtesy Bernice Steinbaum Gallery, Miami

Silence lies at the heart of Dola de Jong’s The Tree and the Vine (Transit Books, $15.95), a short novel of unrequited desire set in Amsterdam on the eve of World War II. Published in 1954, and newly translated from the Dutch by Kristen Gehrman, it follows two young women who share a garret apartment and an unspoken mutual attraction: Bea, a sensible middle-class woman who works as a secretary, and Erica, a mercurial journalist who likes to drink and dream, and who dresses like a member of the Socialist Youth.

Erica is fairly straightforward about seducing her new roommate. She arrives at their apartment without a bed, and replies only with “a shy, crooked smile” when Bea asks why. The advance doesn’t work, and Erica spends several weeks sleeping on the floor. Meanwhile, she builds her own furniture from castoffs found on the sidewalk, letting Bea furtively admire her industry:

I’d leave Erica bent over her work with a knee on the wood and a saw in her steady hand, a straight lock of hair hanging over her eyes, her sports blouse dark with sweat. The sound of her sawing and pounding echoed down the canal.

What follows is a sharp and erotic domestic drama, sometimes comic yet darkened by the looming Nazi occupation. Bea, who narrates the story from a new life in postwar America, largely ignores her roommate’s attraction, even as she assumes spousal responsibilities. (She enforces financial chastity by managing the free-spending Erica’s checkbook.) When Bea brings home a man, Erica sings Dutch folk songs outside the bedroom. Erica retaliates when they travel to France, abandoning Bea to mope like a martyr while she enjoys the lesbian hangouts of the Côte d’Azur with an American divorcée. The situation escalates when they return to Amsterdam. Nazism seeps into their social circles, slowly at first, then all at once with the German invasion. At the same time, and a little too conveniently, Erica learns that her unknown father might be Jewish.

The denouement sees Bea scrambling to engineer their escape as Erica falls into a series of fraught affairs with violent women—and, eventually, joins the Dutch Resistance. Erica’s restlessness and Bea’s obstinacy destroy any chance of fleeing together, but their increasingly high-stakes standoff makes for some slashing arguments. “We’re two old spinsters living upstairs,” Erica fumes during one brawl, forecasting a future of monotonous outings with married friends. “And Wednesday night you’re invited out for flapjacks with Dottie and Max and their snot-nose kids. Flapjacks and whining children. What a treat!” Bea subsequently cuts herself on a bread knife.

In Yukio Mishima’s novel Confessions of a Mask—another midcentury queer classic—war comes as a relief to the closeted narrator, whose expectation of certain death defending the homeland makes confronting his homosexuality seem immaterial. Similarly, Bea writes that “war offers a way out for people who’ve been backed into a corner . . . who quietly hope for an external tragedy to come along and put an end to [their] unbearable situation.” Neither character finds that escape is quite so easy; as many in our own time have discovered, disaster and domestic confinement have a way of eliciting revelations.