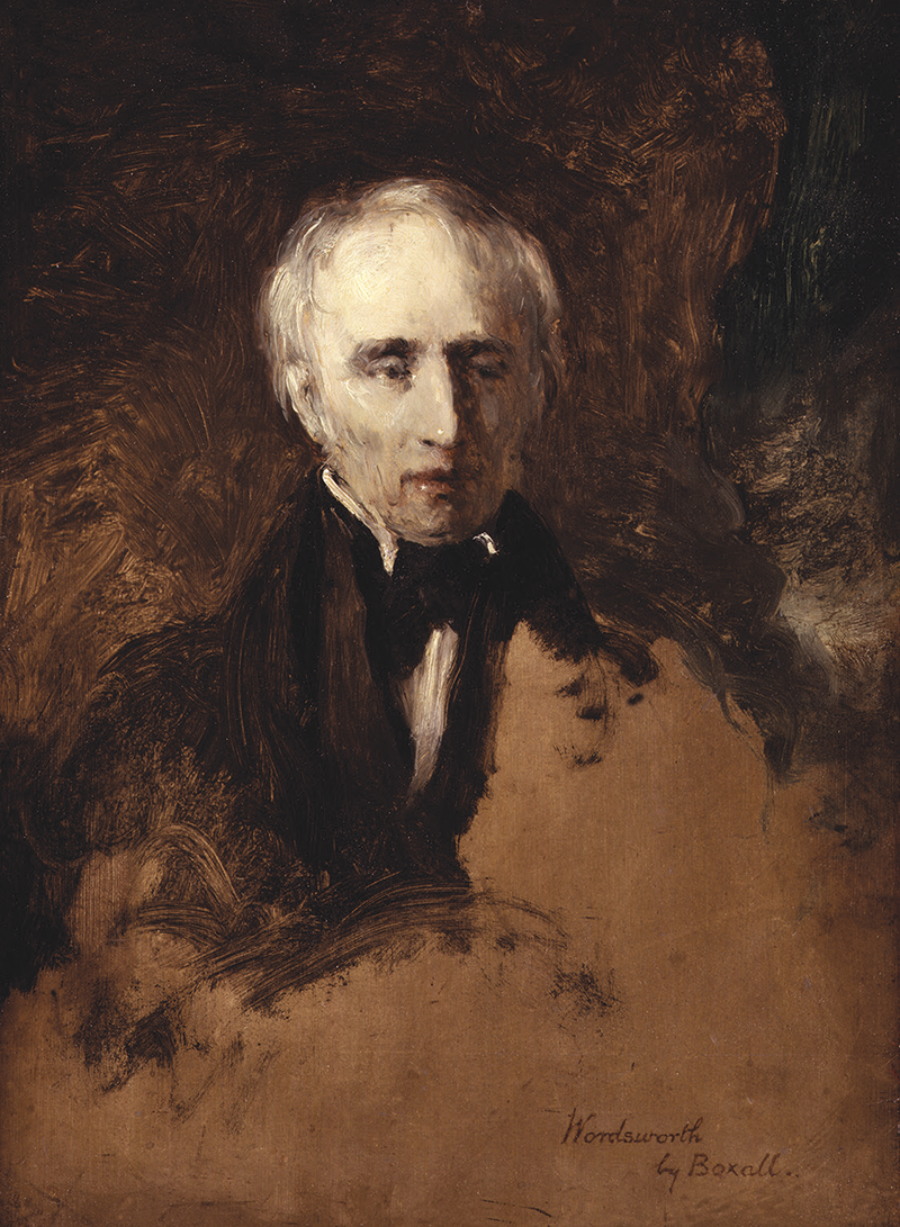

William Wordsworth, 1831, by Sir William Boxall © National Portrait Gallery, London

Discussed in this essay:

Radical Wordsworth: The Poet Who Changed the World, by Jonathan Bate. Yale University Press. 608 pages. $35.

William Wordsworth: A Life, by Stephen Gill. Oxford University Press. 688 pages. $32.95.

The Making of Poetry: Coleridge, the Wordsworths, and Their Year of Marvels, by Adam Nicolson. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 448 pages. $35.

“I feel like the first men who read Wordsworth. / It’s so simple I can’t understand it.” Randall Jarrell’s bemusement is a reminder that, from the start, Wordsworth has provoked people to wonder what they want from…