We Shall Not Be Moved

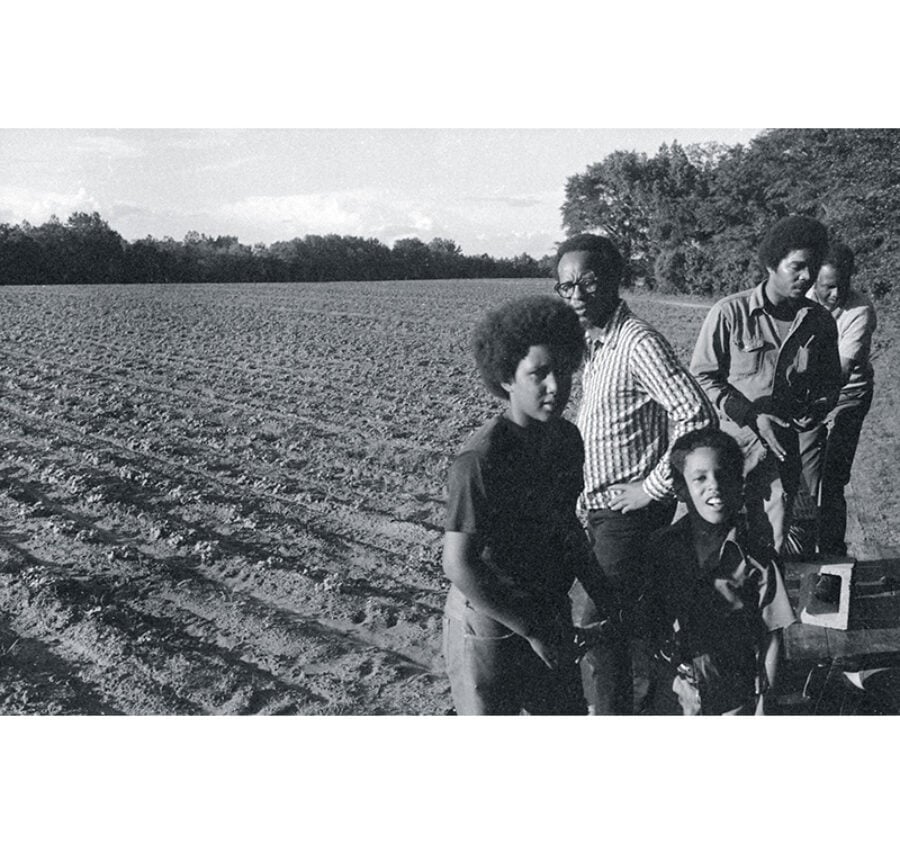

Charles Sherrod (second from left) at the New Communities farm in Georgia, 1973. Photograph by Joe Pfister. Courtesy New Communities and Open Studio Productions, from Arc of Justice: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of a Beloved Community

Decton Hylton guided his tractor through a grove of pecan trees whose canopy of leaves filtered the sun. As we drove across the 1,638-acre farm near Albany, Georgia, on a scorching day last October, Hylton told me about the nut’s history in the South. In the nineteenth century, he said, an enslaved man known only as Antoine, who worked as a gardener on a Louisiana plantation, was one of the first people to experiment with grafting pecan trees. He was largely responsible for turning the nut into a commercial crop, and the variety he developed is called Centennial. “It’s…