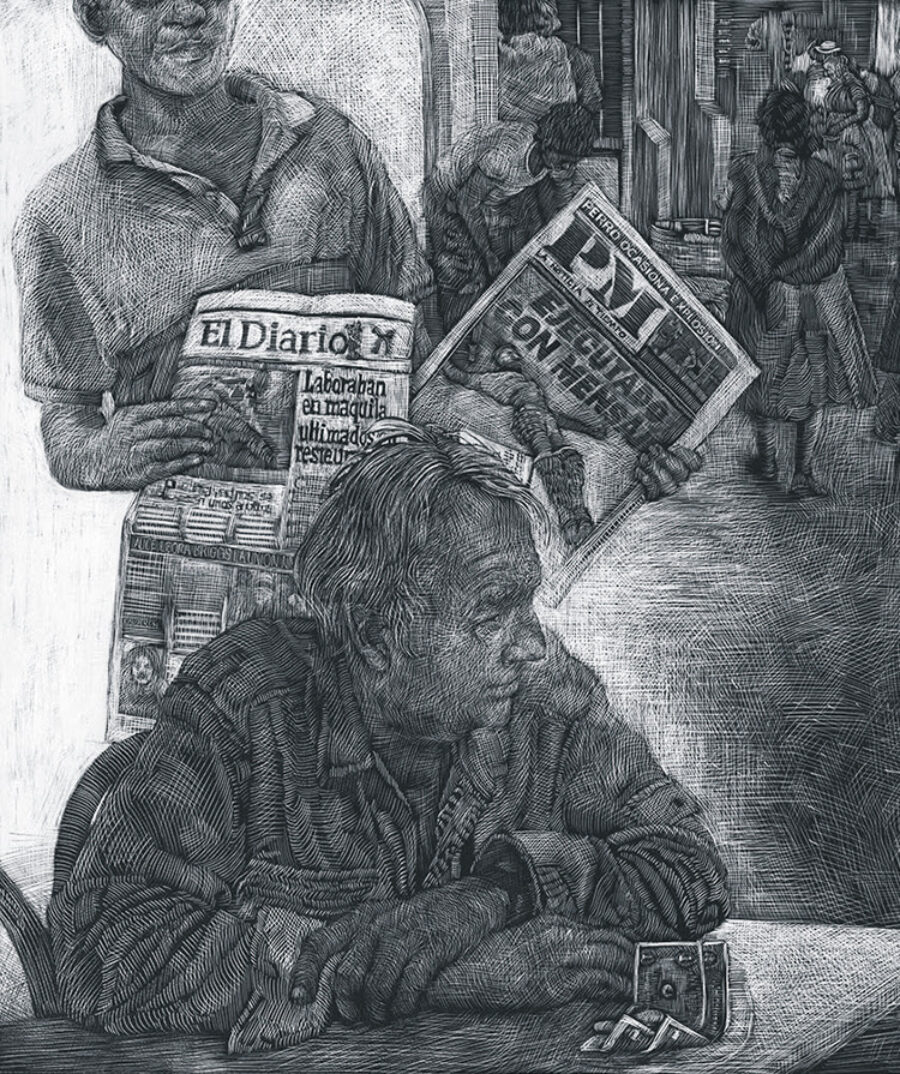

Tocino fresco (detail), a sgraffito portrait of Charles Bowden, by Alice Leora Briggs © The artist. Courtesy Evoke Contemporary, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Etherton Gallery, Tucson, Arizona; and the University of Texas Press

Discussed in this essay:

America’s Most Alarming Writer: Essays on the Life and Work of Charles Bowden, edited by Bill Broyles and Bruce J. Dinges. University of Texas Press. 352 pages. $29.95.

Dakotah: The Return of the Future, by Charles Bowden. University of Texas Press. 184 pages. $24.95.

Jericho, by Charles Bowden. University of Texas Press. 240 pages. $24.95.

Blue Desert, by Charles Bowden. University of Arizona Press. 224 pages. $19.95.

The Red Caddy: Into the Unknown with Edward Abbey, by Charles Bowden. University of Texas Press. 120 pages. $16.95.

The journalist Charles Bowden first heard about the sicario, a member of the Chihuahua State Police who moonlighted as an assassin for a Ciudad Juárez drug cartel, in 2008. An acquaintance of Bowden’s had been harboring the killer after he found God and fled the cartel. The sicario’s former jefes had put a $250,000 hit out on him, and he was ready to confess everything he had done. Bowden, then in his early sixties, leaped at the opportunity to meet him. He had been reporting on the brutality along the U.S.-Mexico border since the early 1980s, and had been waiting for a moment like this for decades. Though he had interviewed countless victims over the years, he had never encountered a murderer who was willing to speak in detail about his crimes.

When the sicario and Bowden finally met, in a border-town motel room, the assassin spoke of the contract killings he’d committed, in plain but disturbing detail—the bodies boiled alive, sliced up, pumped full of amphetamine to prolong their suffering. His right arm had grown muscled from years of strangling victims. But as the assassin described his disillusionment with a life of violence, Bowden came to admire him, and even to recognize, in the arc of the killer’s career, some part of his own trajectory as a reporter:

We are both trying to return to some person we imagine we once were, the person before the killings, before the torture, before the fear. He wants to live without the power of life and death, and wonders if he can endure being without the money. I want to obliterate memory, to be in a world where I do not know of sicarios and think of dinner and not of fresh corpses decorating the calles. We have followed different paths and wound up in the same plaza, and now we sit and talk and wonder how we will ever get home.

Bowden had started out in his late twenties writing about the Southwest’s aquifers and orchids and turtles, but ended up as one of the premier non-fiction chroniclers of drug mules and gangland executions in the Arizona and Texas borderlands. In more than a hundred magazine articles and twenty-eight books, he developed a distinctive style that combined investigative reporting and nature writing, confessional essay and muckraking exposé. He confronted a blithely uninterested American public with the despoliation of the deserts, the dehumanizing horrors of migration, and the brutal business of the drug market. He wrote about the Sonoran Desert from both sides of the Rio Grande, a landscape, as the writer William deBuys puts it in a new book, America’s Most Alarming Writer: Essays on the Life and Work of Charles Bowden, “straddling the life-warping division of the international border, a place inhabited by campesinos, artists, drug runners, fat cats, hunters, and hustlers: el desierto.”

Bowden’s attitude toward nature was dystopian and irreverent, a tonic for what he thought was the sanctimony of the Sierra Club crowd. (“Environmentalism,” he once said, “is an upper-middle-class, white movement aimed at absolution and preserving a lifestyle with a Volvo.”) He was attuned not to the beauty of biology but rather to its ugliness, which served as a reminder that all life is caught up in the same web of desires—hunger, pain, fear. Just as he would later insist Americans look unflinchingly at the reality of the drug war, in his ecological writing he insisted readers look more intently at the war modernity had waged against the nonhuman world, particularly in the vast expanses of the Southwest.

Bowden affected a hippie-cowboy persona, carrying a pistol and wearing huarache sandals. To suss out a story, he would drive into town in his beat-up blue Ford Ranger and ask, “Who’s the most fucked-up person here? I gotta go talk to him.” But he was a disciplined investigator, and he spent years cultivating a broad range of sources—sex workers, cartel jefes, and undercover DEA agents, among many others—who told him their stories, because they too wanted, as Bowden wrote in his 2002 book Down by the River, “some record made of this war that goes on silently with no one the wiser.”

His antics, both on and off the page, were sometimes troubling. His female characters are almost always victims, his men always killers, and his depictions of women are often cringeworthy—dead or alive, there’s usually mention of their breasts. In 1989, Bowden drunkenly assaulted a female journalist for asking him about his just-deceased friend, the novelist Edward Abbey. “I will not make excuses for violence,” he writes in The Red Caddy, a memoir of his friendship with Abbey. “Especially my own.” Bowden has also been criticized, fairly, for conjuring an excessively dark vision of Mexico, and being “in love with the abyss” of violence, as a critic once put it.

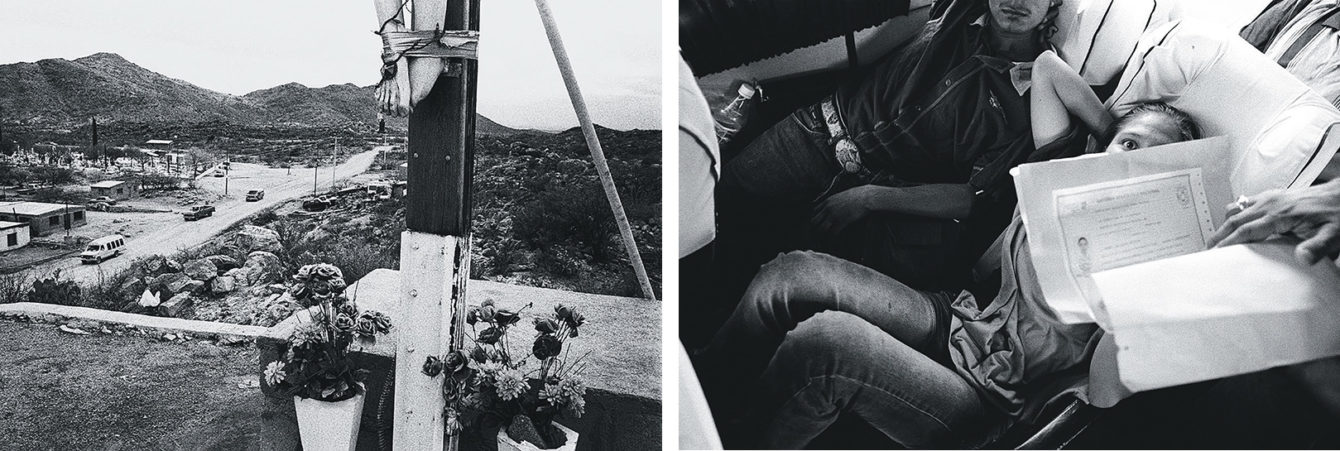

Left: Vans full of migrants in Sasabe, a town along the U.S.-Mexico border, 2003. Right: Migrants being questioned by an immigration officer in Hermosillo, Mexico, 2004 © Julián Cardona. Courtesy the University of Texas Press

But years after his death from a heart attack in 2014, at age sixty-nine, his work continues to inspire scores of reporters and essayists dedicated to documenting life in el desierto—Francisco Cantú, Reyna Grande, Lauren Markham, Jean Guerrero—all of whom, in writing about the people who exist on America’s margins, push forward the journalistic project Bowden helped initiate. “I think he moved the conversation,” the author Luis Alberto Urrea said after Bowden died. “He was able to get the conversation to people who didn’t think about it. I don’t know that he thought you could change anything. He kept saying that [U.S.-Mexico migration] was the greatest tragedy and human movement in history and being completely ignored, being erased. He wanted it on the record.”

To create this record, Bowden woke at 3 or 4 am each day and, fueled by coffee or red wine and cigarettes, wrote for as many as sixteen hours, producing fifteen thousand words a week. When he died, he left behind four* unpublished manuscripts, the first three of which, Dakotah, Jericho, and The Red Caddy, were recently published by the University of Texas Press, to be followed in coming years by the remaining five. These three new volumes are accompanied by the reissue of six of his out-of-print works, and America’s Most Alarming Writer, an essay collection by his friends and admirers, including Jim Harrison and William Langewiesche. Together, these books present an opportunity to get to know an author whose work helped change our image of the Mexican borderlands from a place where disaster touches only impoverished migrants to a place where disaster touches, and incriminates, nearly all North Americans.

As Bowden recounts in the autobiographical Dakotah, he was born in 1945, and spent his early years living on a 160-acre farm near Joliet, Illinois, until his family moved into an apartment in Chicago. When Bowden was twelve, his father, an alcoholic, uprooted the family again and—seemingly on a whim—took them to Tucson, Arizona. In college Bowden became obsessed with the Southwest’s rapidly depleting aquifers, a subject he pursued in a PhD program in intellectual history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. But he abandoned academia in his mid-twenties, after his dissertation—an unwieldy, Faulknerian mess about groundwater—was rejected, and rather than revise it he returned to Tucson, where he worked as a reporter for one of the city’s two big dailies, the Tucson Citizen.

The Citizen was known as “a haven for drinkers and smokers and pseudocowboys,” and it was there that Bowden began constructing his persona as a gunslinging tough guy. According to Norma Coile, a colleague at the Citizen, Bowden bragged that he’d “bedded every woman he’d written about.” He also liked to boast that “someday all Arizona civilization would collapse.”

In spite of all this, he eventually won over his colleagues. “Over time,” another of Bowden’s co-workers recounts in Most Alarming, “I realized how much better a journalist Chuck was than any of the rest of us at the Citizen.” When no one else would, Bowden took over the sex-crime beat. In 1984, Bowden was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in feature writing, and the selection committee named him the winner. He was recognized for two articles, one on child abuse, the other on migrants, for which he’d gone undercover and hiked across the border in one-hundred-plus-degree heat. His reporting preceded much of the country’s attention on immigration; his article appeared three years before Ted Conover’s extraordinary account of a similar journey, Coyotes, was published to much acclaim, and a decade before Urrea’s 1993 Across the Wire. (When Urrea’s book came out, Bowden bought forty copies and gave them to his friends.) But the prize decision was overruled by the Pulitzer family without explanation and Bowden was demoted to finalist, a snub that established a pattern for the type of this-close success that would define his career.

To help deal with some of the trauma he’d suffered from covering the “kiddie fuck” beat, as he called it, he began undertaking masochistic hundred-mile solo treks through the desert, and after three years he quit the paper. “I would write up these flights from myself,” Bowden later recalled, “and people began to talk about me as a nature writer.” The resulting books are deep explorations of bat caves and border towns and the wilderness of his own psyche. Perhaps the best of them is Blue Desert, published in 1986. In discursive chapters on antelope, minnows, Earth First!, the Glen Canyon Dam, smugglers’ routes, and strip-club murders, Bowden details the effects of American mass migration to the Sunbelt in the 1970s and 1980s. “There is not much difference between the proud new Sunbelt cities and the old mining camps,” Bowden writes. “They will exhaust the place and then move on. I should say: we will exhaust the place and then move on.” In a chapter about an endangered bat colony—its population had been decimated by DDT, dwindling from fifty million to fewer than twenty-five thousand—Bowden immerses himself in the muck of existence. Upon entering the cave, he writes:

We climb. The hills of feces roll like trackless dunes. . . . Something is crawling up our bare legs, across our bellies, down our arms, past our necks and onward into the curious contours of our faces. Mites move up from the dunes of feces and explore us like a new country. When we pause and look up, our eyes peer into a mist, a steady drizzle of urine and feces cascading from the ceiling.

I have no desire to leave.

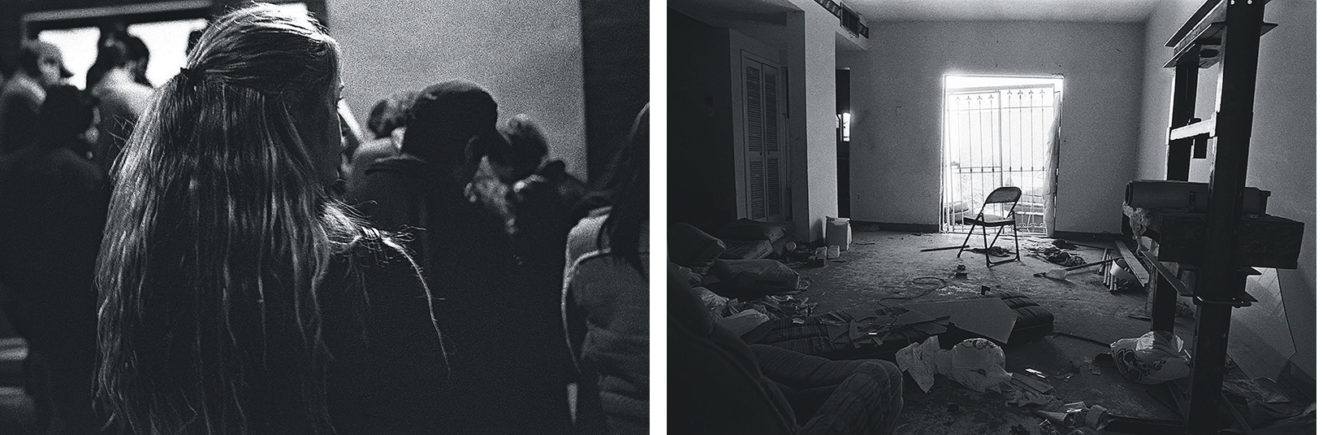

Left: María Esther García visiting the Ciudad Juárez morgue in 2004, two years after her brother disappeared. Right: The so-called House of Death in Ciudad Juárez, where in 2004 the police discovered twelve bodies buried under the patio © Julián Cardona. Courtesy the University of Texas Press

Bowden used the same keen eye for ecology to illuminate the often invisible journeys of migrants. In Red Line (1989), his first book with a major publisher, he set out to meet an assassin named Nacho, who kills people with a screwdriver. He wanted to understand what transformed Nacho into a killer. To find him, Bowden walked across the desert, with just a backpack and a notebook, sleeping on the sand. He doesn’t find the killer, but he does find the crumb trails of migrants, and unearths their exodus with an archaeologist’s attention to the soil.

The culverts under the big road are rich with artifacts: hundreds of human footprints heading north, big empty cups of 7-11’s Super Big Gulp. Here and there erupt the tire tracks of the Border Patrol, then the machine stops, and huge American footprints briefly join the legion of feet walking into El Norte. The American impressions stand for the rules, black coffee, and endless forms. The Mexicans stand for the appetites.

In the desert, Bowden had found the perfect theater for his interests and his persona, a stage upon which to watch unfold the drama of man versus nature, civilization versus wild instincts, a place defined by scarcity and stinginess, where dark tensions came into stark relief. In a talk Bowden gave at Tucson’s Pima County Public Library, he explained that he’d reached “certain conclusions” after years of writing and living in Arizona, one of which was that the best way to understand something was to go to its margin:

This desert was the edge of natural resources as Americans understand the term, and here in its heat and persistent droughts I could make sense of all those dull terms like the “environment” or “ecology.” I believed, and still believe with every bit of my being, that the future is going to be a collision between limited resources and unlimited human appetites.

In the mid-1990s, Bowden’s interest in the destruction of the desert led him to Juárez, where he discovered an ecological and humanitarian catastrophe far more dramatic than anything he’d seen on the American side of the Rio Grande. He first learned of a spate of unsolved rapes and murders in the city when he was reading a crime tabloid and saw a photo of a young maquiladora worker who’d been killed, Adriana Avila Gress.

She was smiling at me and wore a strapless gown riding on breasts powered by an uplift bra, and a pair of fancy gloves reached above her elbows almost to her armpits. The story said she’d disappeared, all 1.6 meters of her.

By that point Bowden had been out of the newspaper game for two decades, but the femicides in Juárez—the spike in unsolved rapes and murders of hundreds of women, especially young workers at the maquiladoras that had sprung up all along the border since the enactment of NAFTA—must have felt like déjà vu. He kept Avila Gress’s photo in his desk drawer, as if she were his muse, and carried it with him as he poked around Juárez, reporting on the crimes and economic policies that had transformed the city. Cheap U.S. corn had flooded southern Mexico, ruining two million farmers’ livelihoods and forcing many to migrate north to the border zone in search of poorly paid manufacturing jobs at foreign-owned companies such as General Electric and Walmart. Wages dropped by 12 percent, and union membership was halved. It was the beginning of our present migration crisis, and Bowden saw the United States as a quasi-colonial power exploiting Mexico. “Juárez stares at our imperial state,” he once said, “and demands that we explain its destruction at the hands of our drug policy, our economic policy, and our immigration policy.”

In “While You Were Sleeping,” an article that first appeared in these pages, Bowden tells the story of Juárez’s apocalyptic transformation from the perspective of the street photographers chasing ambulances and documenting mutilated corpses. What they captured, he said, was

the look of the future. This future is based on the rich getting richer, the poor getting poorer, and industrial growth producing poverty faster than it distributes wealth. We have models in our heads about growth, development, infrastructure. Juárez doesn’t look like any of these images and so our ability to see this city comes and goes, mainly goes. . . . These photographs literally give people a picture of an economic world they cannot comprehend. Juárez is not a backwater, but the new City on the Hill, beckoning us all to a grisly state of things.

His newfound focus on the drug war earned him plum magazine assignments for Esquire and National Geographic, and like many gringo reporters before him, it also provided a backdrop for a roguish personal mythology. Most Alarming helps separate some of the facts from fantasy. It even confirms a few of his wilder tales, though it offers an incomplete and anecdotal accounting of Bowden’s biography. We hear firsthand recollections from his second wife, Mary Martha Miles—also Bowden’s literary executor—seeming to confirm stories he told for years that many doubted, such as how, in retaliation for an exposé Bowden had published in GQ, the head of a Juárez cartel paid a local newspaper to publish Bowden’s home address on its front page. On two separate trips to Juárez, Miles claims, somewhat astonishingly, “I was with him in Mexico [and] he evaded cartel men who were chasing us toward the border with their guns drawn.”

As Bowden’s reporting on the drug war consumed his writing, his personal life increasingly mirrored the lives of the people he wrote about. He drank jugs of Gallo wine for lunch. Miles says he was abusive. In the spring of 2009, after she’d worked as his secretary and editor for nearly a decade, revising his work and typing up his manuscripts, Bowden left her, only to return six months later, begging for permission to come back to their Tucson home. She agreed, but only if he entered rehab to deal with his drinking and “the abuse he had exhibited toward me during the last few years we were together.” Bowden refused. From then until his death in 2014, he split his time living in Jim and Linda Harrison’s place in Patagonia, Arizona, and with a new girlfriend in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

As Bowden lived more and more like a hard-boiled DEA agent, he began to think like one. His book Down by the River, a story about the murder of the brother of a DEA agent named Phil Jordan, was widely praised for the depth of its reporting. Bowden spent years crisscrossing Mexico and the Southwest trying to solve the case. Jordan writes in Most Alarming that Bowden “single-handedly did more in solving my brother’s murder than the El Paso Police Department, or any other agency.” But in his pursuit of the killer, Bowden was increasingly obsessed with violence, his views coming to resemble those of the detectives who were his friends and sources. Like these men who had never set foot in Mexico without a weapon, who saw crime and violence everywhere because it was their job to look for it, Bowden too took it as his job to look for crime and violence. Often, that was all he could see, and in later books, such as 2010’s Murder City—a portrait of Juárez told largely through the stories of the residents of a local mental hospital—his characters lost the humanity he once imputed to them, becoming mere objects for suffering, harbingers of horror. “I have not entered the country of death, but rather the country of killing,” he wrote in Murder City. “And I have learned in this country that killing is good.”

Passages like this led critics to accuse Bowden of peddling a lurid, sinister image of Mexico, of seeing the country through “shit-stained glasses,” as one of his acquaintances put it. Toward the end of Bowden’s life his cynicism threatened to engulf him. (“Once I was hungry for any glimpse inside [the] secret world” of murder and drug violence, he explains in Jericho, written a few years before his death. “I am no longer hungry.”) Of course, maybe he saw shit everywhere simply because, like the Juárez photographers he’d once profiled, he had seen the future. In his work, Bowden prophesied many of the bleakest forces that would come to define border politics—the fear and demagoguery, the economic desperation, the official lies, the indifference to suffering. He may have believed Mexico was hell, but only because he believed America was hell, too, a country where he predicted a charlatan politician might one day try to “create a country so repellent that no one will sneak into it.” Bowden’s obsessive focus on darkness was at least in part an attempt to warn readers of this impending disaster. “We either find a way to make their world better,” he once wrote, “or they will come to our better world.”

For all his cynicism, Bowden’s response to this crisis was never a desire to strengthen the border, but rather to destroy it. “There aren’t any Mexican stars or American stars,” he once said in a radio profile, as he hiked with the correspondent through the Buenos Aires wildlife refuge in southern Arizona, a popular route for migrants sneaking into the United States. “It’s like a great biological unity with a meat cleaver of law cutting it in half.” His work was an attempt to heal this cleavage, and to remind us how our hunger, pollution, and violence connected us all, especially in the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts, where nature was a stingy mother and death ruled over everything. “We are becoming more and more aware that our civilization destroys the foundations that support it by devouring the earth and the things of the earth,” he wrote in Blue Desert. “But we don’t have the courage to back away, to stop, to restrain ourselves. I know I don’t.”

Like the beasts and criminals he admired, Bowden was a complicated, contradictory creature. He loved dogs, dirt, wine, worms, Cadillacs, cacti. He held backyard parties to watch summer cereus flowers bloom at midnight, and owned scores of guns but was reluctant to shoot them lest they scare the birds. In Most Alarming, a priest named Gary Paul Nabhan reports that the last time he saw Bowden the surly old tough guy was weeping for a cottonwood tree that had died. Bowden’s teeth were falling out. He was poor and owned little more than a laptop, a Le Creuset pot, a sleeping bag, a Honda Fit, and a pair of binoculars. If in life he sometimes failed to be a decent man, in his writing he tried to be a better animal. “The whippoorwill’s name reflects the sounds we hear it make,” he once wrote in a letter to a friend.

But studies show there are two more notes to its song beyond the range of human hearing. Scholars wondered if other birds heard these notes, and recordings of mockingbirds, a species that mimics the songs of other birds, revealed that they did. . . . I want to hear these missing notes about the border and the ground about us when I write and bring the full song to the attention of others.