If it weren’t for the black death, the fourteenth-century merchant Francesco di Marco Datini might have left no trace in history. A workaholic Tuscan with offices from Bruges to Barcelona, he spent most of his time scribbling letters, often boasting that he slept only four hours a night. He kept his wife busy distilling vinegar, entertaining visitors, and sewing helmets for the arms trade; Datini himself, meanwhile, was married to the game of late-medieval commerce. At the time, it was considered a perilously sinful hustle. One friend warned the merchant that he was “a man who kept women and lived only on partridges, adoring art and money, and forgetting his Creator and himself.”

A depiction of the 1350 Battle of Calais, from an edition of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, circa 1475. Courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France

Luckily for scholarship (and his own immortal soul) a plague prompted Datini to organize his papers and bequeath his small fortune to “God’s Poor.” His palazzo in the Italian city of Prato became the office of a charitable foundation, still in operation. There, his letters and ledgers sat forgotten in the cupboards for nearly half a millennium—awaiting, in lieu of the Last Judgment, the arch assessment of Iris Origo. An English-American writer turned Italian aristocrat, Origo is now largely remembered for her diaries of life under Mussolini. But she was first of all a biographer, with a talent for inhabiting the outlook of subjects that ranged from antifascist fighters to medieval saints. Her newly reissued 1957 study the merchant of prato (New York Review Books Classics, $19.95) is a stylishly written and startlingly immersive portrait of Datini as a trecento trader on the make.

Born in Prato around 1335, Datini set out for Avignon at fifteen, orphaned by the same plague—the first of six in his lifetime—that inspired Boccaccio’s Decameron. He made a fortune selling armor and weaponry, as well as splendid vestments for the clotheshorses of France’s short-lived papal court. Later, he married and returned to Prato, establishing a textile company with dealings across Europe. Origo evokes a precarious trade beset by schisms, bandits, and other dark-age externalities, where merchants routinely fall victim to marauding condottieri:

[Datini] lived in daily dread of war, pestilence, famine, and insurrection, in daily expectation of bad news. He believed neither in the stability of any government, nor the honesty of any man. . . . And it was by this caution, this unceasing vigilance, that he made his fortune. But it was a weary life.

Ambitious, exacting, and exceedingly stressed out, Datini cuts a cranky yet companionable figure in correspondence with loved ones and far-flung subordinates. He fumes at absentminded underlings—“You cannot see a crow in a bowlful of milk!”—nitpicks in relatives’ kitchens—“Do not place garlic before me, nor leeks nor roots”—and frets over the delivery of an expensive mule from Spain. Animals are a recurrent extravagance; one approach to fourteenth-century social climbing, it seems, was to buy your cardinal a fancy dog. Datini gave Bologna’s a Catalonian mastiff, which came equipped with a scarlet coat “to wear upon the mountains.”

A worldly striver in a walled country town where “leeks and beans grew at the foot of the battlements,” Datini struggled to reconcile his prematurely modern vocation with the norms of his rustic society. This moral drama vividly unfolds in his private letters, which are among the most detailed surviving records of medieval marriage and friendship. Datini constantly quarreled with his wife, Monna Margherita, about housekeeping, which he micromanaged by mail while traveling for work. “Remember to wash the mule’s feet,” was a typical command. “Would God you treated me as well as you do her!” was a typical rejoinder.

He also wrote to Ser Lapo Mazzei, a devout friend who encouraged the merchant to abandon the vexations of commerce for a simpler, more charitable life. Mazzei’s tough-love letters remain moving—and, as global ties tear, surprisingly relevant. Datini may have been an outlier in his era, but the precarious webs of exchange that obsessed him have since ensnared us all. Mazzei’s advice to rely less on the world and more on one’s neighbors has rarely seemed wiser.

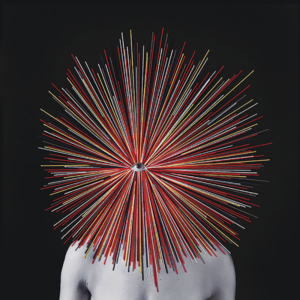

Wondering Eye, by Marina Font © The artist. Courtesy Dina Mitrani Gallery, Miami

Mazzei prescribed philanthropy for his friend’s metaphysical distress; for bodily illness, he recommended theriaca, an ancient mystery medicine that doctors distributed from cauldrons during plagues. Another panacea was a round, jewel-like stone formed in the stomachs of some ruminant animals, called a bezoar. It’s an apt title for the Mexican writer Guadalupe Nettel’s grotesque and beguiling collection of stories. bezoar ($15.95, Seven Stories Press) is a pocket bestiary of compulsives and fetishists, from an “olfactionist” who scours restaurant bathrooms for the scent of an elusive woman to a medical photographer aroused by images of patients’ irregular eyelids:

The photographer has to avoid blinking at the same time as his subject and capture the moment when the eye closes like a teasing oyster. I’ve come to believe that this work requires a special intuition, like an insect collector’s, that there’s not much difference between the flutter of a wing and the batting of an eyelash.

The photographer’s kink mirrors Nettel’s fascination with oddity and inwardness. A recipient of Spain’s Premio Herralde, Nettel is best known for The Body Where I Was Born—an autobiographical novel about growing up in a family that wanted to “fix” her own congenital eye deformity. She has described the early stories collected in Bezoar as reflections on “the beauty of anomaly.” They are just as much meditations on prying and privacy.

In an excellent translation by Suzanne Jill Levine—editor of Penguin’s collected volumes of Jorge Luis Borges—Bezoar offers a disconcerting pleasure, akin to the uncanny intimacies of Edgar Allan Poe and Diane Arbus. Perhaps the strongest story is “Bonsai,” whose narrator frequents a botanical garden for the sheer pleasure of keeping a secret from his wife. His innocent conversations with an elderly gardener lead to the dissolution of his marriage, as he fixates on the idea that he is a spiny cactus, and his wife a rapacious climbing vine. In another confessional vignette, a woman delights in watching her neighbor masturbate in front of his kitchen window while his unsuspecting date, visible in another room, waits wearing a “little black dress she now wouldn’t need to take off.”

Bezoar’s narrow, dreamlike attention invites unconscious complicity: caught up in dramas of curiosity and concealment, one forgets, momentarily, that the narrator is a man who interprets toilet-bowl skid marks or a woman who can’t stop eating her own hair. Nettel makes it impossible not to notice the latent voyeurism of short fiction, a genre that fixates, much like a fetish, on fragments of strangers’ inner lives.

A dose of voyeurism is indispensable to political charisma, whose adepts always surrender at least some of their selves to supporters. It may even have played a role in the rise of modern democracy, as the spread of newspapers and literacy gave ordinary citizens an unprecedented opportunity to peer into their leaders’ personal lives. Names like Washington and Bolívar elicited love from millions, whose devotion ushered in the hero-worshipping Age of Revolution. Monarchies grounded in tradition yielded to republics founded on principle and led by “exceptional” military men. In men on horseback ($30, Farrar, Straus and Giroux), the historian David A. Bell investigates the intertwined origins of charismatic authority and modern democracy through the careers of four great equestrian saviors: George Washington, Napoleon Bonaparte, Toussaint Louverture, and Simón Bolívar.

An untitled photograph from the series Hallucinations by Justin James Reed © The artist. Courtesy Candela Gallery, Richmond, Virginia

Many have written about these men, but few have asked why their type emerged when it did. Bell finds the Ur–man on horseback in James Boswell’s 1768 travelogue An Account of Corsica, which included an ecstatic description of meeting Pasquale Paoli, then leader of the island’s struggle for independence. It made Paoli an international celebrity. “I saw my highest ideal realized,” Boswell wrote, gushing about the Corsican’s courage, intellect, and physique, which he’d had a chance to admire while watching Paoli dress. Before Boswell departed, Paoli gave him a fancy scarlet suit and a dog. The writer nearly collapsed from emotion.

We may live in an age of book-length political fan fiction, but in the eighteenth century, close attachments between leaders and the public were highly unusual. Monarchs shunned applause and cultivated an authority based on the mystique of the throne. By contrast, Boswell fashioned his Paoli after classical heroes and the protagonists of sentimental novels. Readers could follow his battlefield exploits in newspapers like a serial fiction, or contemplate his enlightened visage on cheaply printed portraits. His rebellion was ultimately defeated, but another, younger Corsican was taking notes.

One of Bell’s insights is to see the man on horseback as a genre. His engaging survey of the four major early-modern revolutions traces the way their messianic leaders learned from and imitated one another, as did the chroniclers who gilded their names. Napoleon had the comte de Las Cases, who recorded his exile on St. Helena; Washington had Mason Locke Weems, who invented the cherry-tree myth; and Toussaint Louverture had Étienne Laveaux, the governor of Saint-Domingue, whom he’d rescued from a massacre during the Haitian Revolution.

For all except Washington, celebrity nourished dictatorial dreams. But it was also indispensable in shaping fractious kingdoms and colonies into modern republics. “It is easier to love a person than to love a constitution,” Bell writes. “But the love for one can help promote love for the other.” He leaves a yet more provocative argument for the epilogue. If historians once narrowly construed their discipline as the study of major leaders, Bell suggests that the pendulum has since swung too far in the other direction, with even the most consequential figures seen as little more than fleshy embodiments of social forces. He calls on historians to write charisma back into their scholarship.

Not that Bell wants a reactionary return to the great-man school of Carlyle and Plutarch. Rather, he advocates for the cultural study of leadership, of the way that shifts in technology, religious belief, and literary taste shape the exercise of personality-driven power. Charismatic leadership may depend as much on cultural savvy as on strategic brilliance. Bolívar lost many battles, but he knew what a Mosaic liberator should look like. After climbing Ecuador’s highest mountain, he wrote “My Delirium on Chimborazo,” a Romantic prose poem in which he vaunts his accomplishments to an ancient mountain spirit who accuses him of vanity. “I have surpassed all men in good fortune, as I have risen above the heads of all,” Bolívar, undaunted, replies. “I dominate the earth.”

The powerful may etch their names in marble—or, like Jeff Bezos, furnish their private mountains with clocks designed to tick for ten thousand years—but even gods aren’t safe from natural and man-made weathering. Orkney, an archipelago off the northeastern coast of Scotland, once had a Neolithic monument called the Odin Stone with a perfectly round hole in its center, where generations of Orcadians swore solemn oaths. In 1814, an oblivious farmer clearing land destroyed the stone with black powder charges. Other standing stones had been destroyed more systematically over the previous five centuries, burned and buried by villagers who in some cases believed that megaliths, returned to the earth, could take root and grow.

“Hong Kong Flora,” by Michael Wolf © The Estate of Michael Wolf. Courtesy Flowers Gallery, London/Hong Kong

In the book of unconformities ($30, Pantheon), Hugh Raffles contemplates the curious lives of stones from the Bronx to Iceland, demonstrating that “even the most solid, ancient, and elemental materials are as lively, capricious, willful, and indifferent as time itself.” The author, an anthropologist, has written books about insects and the Amazon, but The Book of Unconformities has a more personal origin: the deaths of two of Raffles’s sisters, one of whom lived on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. A pilgrimage to the nearby standing stones of Callanish leads Raffles to visit other stone circles and to develop a preoccupation with what geologists call unconformities—divides between sedimentary strata that signify breaks in geological time.

The result is a spellbinding time travelogue. Raffles winds his way from New York to the Arctic Circle, and from the breakup of Laurasia to the World War II internment of his grandmother, who sliced mica for Nazi warplanes at a factory in Theresienstadt. Each chapter begins with a stone and carves out the history of a place. “Marble” traces the strange migration of New York’s Marble Hill, which was severed from Manhattan and later attached to the Bronx. “Blubberstone,” named after a word for concreted whale fat, recounts the story of Svalbard, a sparsely inhabited Arctic archipelago strewn with vestiges of extractive industry:

Blubberstone at Smeerenburg, walrus skulls at Kapp Lee . . . expressive objects surfacing from the deep quiet and severe beauty of a landscape that has the quality of a theater from which the actors, audience, and even the ushers have long departed.

Raffles’s dense, associative, essayistic style mirrors geological transformation, compressing and folding chronologies like strata in metamorphic rock. The most mesmerizing section is “Iron,” which tells the history of Greenland’s far north through one meteorite. It struck Earth sometime in the Pleistocene; provided millennia of Inughuit hunters with their only source of iron; and, in 1894, was finally prized from its crater by the opportunistic adventurer Robert Edwin Peary.

Now housed in New York’s American Museum of Natural History, the Innaanganeq meteorite is a testament to the many lives a single stone can live—and also to the callous thefts of Arctic exploration. Back in Greenland, Raffles meets Inughuit who are calling for the meteorite’s repatriation. It wouldn’t be the most miraculous return in their history. That would be the remarkable odyssey of Qitdlarssuaq, an Inuit shaman from Baffin Island in Canada, who restored the forgotten arts of kayaking, archery, and snowhouse building to a faraway Inughuit settlement whose elders had succumbed to a European disease. He began his ten-year journey across the ice to Greenland with two invitations to his companions: “Do you know the desire for new countries? Do you know the desire for new people?”