A police station in Freetown, Sierra Leone, destroyed by the Revolutionary United Front, 1999 © Riccardo Venturi/Contrasto/Redux

In May 1999, Anthony Feinstein, a quiet South African psychiatrist working in Toronto, received a distraught patient at his office. The woman—Patient X—was a war reporter who worked exclusively in conflict zones. She had just returned from a particularly gruesome assignment, which had left her depressed and lethargic. Feinstein noted at the time that she appeared to be suffering from deep and sustained trauma.

During one session, after Patient X described her state of mind, Feinstein asked whether she’d spoken to her employers about her condition. She recoiled.

“If I told my bosses I was emotionally distressed, I would never get back in the field again,” she explained in tears. She’d lose her job. Whatever she felt had to stay hidden.

Feinstein is a research psychiatrist who primarily focuses on patients with multiple sclerosis, studying how they respond to the disease. “I look at behavioral changes,” he told me. “Their depression, their anxiety, how a change in patterns occurs. Basically I’m trying to understand their brains.”

But the journalist with clear symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder weighed heavily on Feinstein. He wondered whether her suffering might have been prevented if she’d had the right training before her assignment or if she’d been treated immediately after returning. Could early intervention alleviate stress-induced depression?

This was the late Nineties, and PTSD was not as widely researched as it is now. Most reporters and humanitarian workers had not heard of it. Feinstein’s knowledge of the affliction came partly from his background: he’d grown up during apartheid and witnessed extreme violence. He knew that soldiers returning from active combat suffered from PTSD, but he’d never heard of a conflict reporter suffering similar symptoms. He asked his research team to compile studies that might provide precedents, but they came back empty-handed.

“They told me there was nothing published on the topic,” Feinstein recalled. “I didn’t believe them. Because in medicine, there is always something that comes before you.”

But the University of Toronto’s medical library did not have a single study on the subject. Feinstein was baffled: there was extensive scientific data on firefighters, police officers, soldiers, and victims of sexual assault, but a void when it came to reporters.

Photographer James Nachtwey offers water to a man in Rwanda, 1994 © Scott Peterson/Liaison/Getty Images

Though sometimes remembered as a more peaceful time, the Nineties were full of bloodshed and misery. The decade was marked by wars in Africa, the Balkans, and the Middle East, often involving extreme violence carried out by paramilitary groups with little regard for international law. In the days before journalists started embedding with troops, those of us who reported on these conflicts were free agents. There were no precautions in place to protect us. Few reporters wore flak jackets or helmets; fewer had insurance or security guards. When we heard news of a war, we jumped on a plane and arrived cold, notebooks or cameras in hand.

Most of my colleagues were freelancers with no conflict training, and the violence in Bosnia, Chechnya, Somalia, Rwanda, Liberia, Sudan, the Congo, and other places was harrowing. Many reporters were killed, many others permanently injured. Several of my friends took their own lives. I was in Somalia in 2002 when I got a call on my satellite phone and was told that Juan Carlos Gumucio, a much-loved Bolivian reporter for El País, had killed himself with a shotgun. Years later, Gumucio’s third wife, Marie Colvin, my colleague and friend, died during a rocket attack in Homs, Syria.

In 2000, I was working in Sierra Leone during a particularly bloody conflict. In mid-May, as Freetown was about to fall to the Revolutionary United Front—a brutal paramilitary group whose signature was to cut civilians’ arms off at the wrist or elbow—I ran into my old friend Kurt Schork, who was on assignment for Reuters. It’s hard, even now, for me to explain how iconic Schork was to his colleagues. He was often described as the greatest war reporter of our time.

Schork came late to journalism—he had been the chief of staff of New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority and a Rhodes scholar alongside Bill Clinton—and he was in his forties when he made his name photographing Kurdish atrocities during the first Gulf War. He was later sent to Bosnia, where I met him during the siege of Sarajevo; he remained in the city for five years.

On Wednesday, May 23, I had dinner with Schork in Freetown, and I handed him a VHS tape that showed RUF members committing atrocities against United Nations peacekeepers. He told me that the next morning he planned to drive to Rogberi Junction, a rebel-held crossroads town northeast of the capital, along with two other reporters and Miguel Gil Moreno de Mora, an Associated Press cameraman and producer who was also among the finest in his field.

I had breakfast with Moreno before they left. We joked about frogs mating in the abandoned hotel where we were staying. Though there were reports that the road to Rogberi Junction was especially dangerous, the group went ahead. Schork and Moreno never came back.

Migrants land on the island of Lesbos, Greece, after crossing from Turkey, 2016 © AP Photo/Santi Palacios

Their murder sent an earthquake through our small tribe of reporters. The event also motivated Feinstein to pursue his study of war reporters and PTSD. He got the names of one hundred and seventy war reporters, one hundred and forty of whom agreed to be interviewed, including me. Our responses to Feinstein’s questionnaires were compared with those of a control group.

Feinstein was alarmed by the results. “I do not believe there is another profession that has more exposure to war than your group,” he told me. While soldiers often served one or two tours, he said, “You go back year after year after year to war.” Feinstein compiled a database of more than a thousand frontline journalists and concluded that the mean time spent in war zones for career war reporters was nearly fifteen years. “You and your colleagues created a bubble around yourselves,” Feinstein told me at the time. “You believed you were neutral observers, and you were immune to harm. Even though you knew more than one—often many—who had been killed. You created this bubble by saying, ‘We are okay. We are fine.’ ”

I was relieved to find out that I did not have PTSD; but it turned out that most of my colleagues did. It showed: alcoholism, depression, an inability to commit to partnerships, and suicide were all symptoms of untreated PTSD.

Feinstein’s study was published to much acclaim in the September 2002 issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry. Aided by former CNN London bureau chief John Owen, Feinstein shared his results with newsrooms around the world to persuade editors to pay attention to their war correspondents’ trauma. Most of them did. His work became a reference point for CNN, the Associated Press, the New York Times, the BBC, and many other news organizations to develop conflict-reporting protocols.

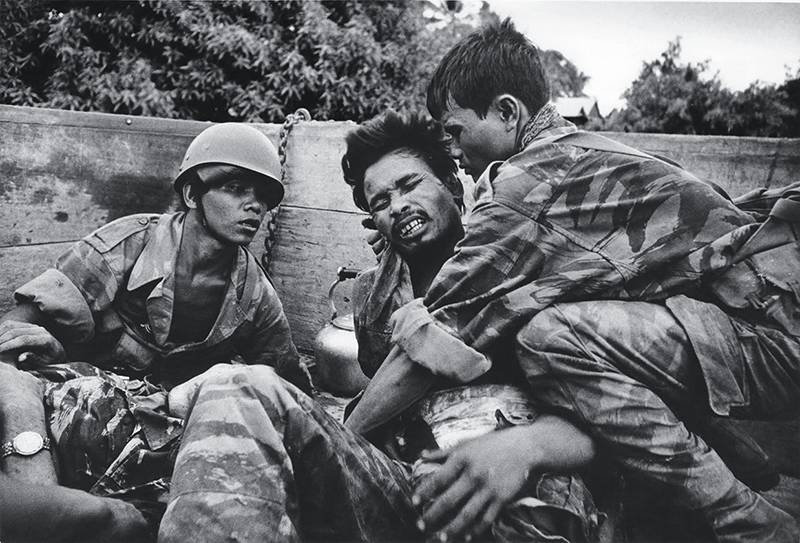

A paratrooper hit by a mortar shell near Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in an attack that also injured Don McCullin, 1970 © Don McCullin/Contact Press Images

In the two decades since Feinstein began studying trauma, PTSD has transformed from a relatively obscure diagnosis into a cultural touchstone. People who don’t know the disorder’s actual symptoms confidently state that they are suffering from PTSD after any number of unpleasant experiences. The widespread embrace of post-traumatic stress as a concept reflects its power not just as a clinical tool but as a framework for how human beings process—or fail to process—trauma.

In 2015, Feinstein began interviewing reporters who were covering the refugee crisis. The flow of people escaping wars in the Middle East, in particular the civil war in Syria, was the largest such displacement ever documented. More than one million women, men, and children attempted to cross the Mediterranean to get to Europe—and more than 3,700 are estimated to have died in the effort—in that year alone.

Unlike Feinstein’s earlier subjects, the reporters covering this humanitarian catastrophe were not themselves at risk; they were not getting shot on the front lines. But he found that a sense of helplessness—the inability to save people from drowning, let alone alter the tragic conditions chasing them from their homes—was causing another kind of mental health crisis. He believed that these journalists were suffering from moral injury.

Moral injury is not a new psychological concept. Jonathan Shay’s 1994 book Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character is a classic study in the field. Shay began his career researching neuropathy, then shifted to working with veterans who had PTSD, devoting his life to helping them adjust to returning home. He argued that PTSD was not an illness, but an injury: the “persistence of adaptive behavior needed to survive a stressful environment.” He compared the homecomings of soldiers in the Iliad with those of Vietnam vets, their devastated lives a result of fighting a war they did not believe in.

Feinstein built on Shay’s work, studying moral injury among conflict reporters. In 2016, he began an initial report with the journalist Hannah Storm for the Reuters Institute, interviewing eighty reporters on the migration beat. He found that

moral injury rather than PTSD or depression emerged as the biggest psychological challenge confronted by journalists covering the migration crisis. . . . Good journalists will of course feel moved by the migration crisis, but they cannot fix it and should not attempt to do so. Guilt, which is often misplaced, can be a faulty motivator of behaviour. So too can moral injury.

Moral injury and PTSD can occur together—this is not infrequent—but they are two separate phenomena. When we spoke recently, Feinstein described moral injury as “a wound on the soul, an affront to your moral compass based on your own behavior and the things you have failed to do.” In other words, rather than being triggered by external actions, moral injury comes from the feeling that one has failed to live up to one’s own ethical standards. Of course, guilt and shame are common responses to such failings, but moral injury occurs “only when symptoms get to a point of impeding a person’s ability to function.”

One example of moral injury that Feinstein comes across frequently is that of photographers feeling that they benefited from the suffering of other people. He told me to picture a lone photographer on a Greek beach focusing his lens on a boat full of refugees in the distance. Suddenly the boat capsizes. The photographer sees that most of the passengers cannot swim and are beginning to drown. “Do you wade in or do you call for help?” He decides to do the latter. He calls for help on his cell phone, and continues to photograph the tragedy in front of him. But his plea for help is too late; many people die in the sea. Later he is lauded for his compassionate work. But guilt and shame gnaw at him for years.

“The photographer who believes he built a successful career on the back of others’ suffering is suffering misplaced guilt,” Feinstein told me. “You can dissect the reasons you are there, but essentially you are there bearing witness. In a sense, you are a contemporary historian.”

Over the years, I have come to know many war photographers, and I have witnessed this phenomenon. The legendary British photojournalist Don McCullin, now in his eighties, has told me repeatedly about his discomfort with the times he chose to continue taking photographs when he felt he should have been helping.

In May 1999, I was in Kosovo with the photojournalist Alex Majoli reporting on the Kosovo Liberation Army when NATO accidentally bombed the unit we were with. While I pulled injured and dead bodies from the trench where we had been sheltering, Majoli continued to photograph the bombs falling from the sky and the wounded soldiers.

“You can always write about this later,” he shouted at me over the cries of pain and the roar of bombs. “I only have one chance to get the evidence.”

Majoli’s work from that day is some of the finest war photography I have ever seen. And we’ve since talked about that question: Are we in the field to bear witness to atrocities, to document history, or to help people? Schork was one of the few reporters I knew who saw his role as a protector of civilians. When a shell landed in Sarajevo, he would haul broken bodies to his car and drive, through the explosions, to the hospital. “It is what human beings do,” he told me once. “Help each other stay alive.”

I often thought about Kevin Carter, a member of the Bang Bang Club, a legendary group of four South African photographers. One of Carter’s most famous photographs depicts a starving Sudanese child collapsed on the ground while a vulture hovers nearby. Carter chased the vulture away, but he was left shocked and full of sorrow. The photo appeared in the New York Times in March 1993. Carter won a Pulitzer for the image. He killed himself four months after winning the prize, on July 27, 1994, at age thirty-three, leaving a note:

The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist. . . . depressed . . . without phone . . . money for rent . . . money for child support . . . money for debts . . . money!!! . . . I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain . . . of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners.

“We are not social workers,” the photographer Corinne Dufka told me during the siege of Sarajevo, when I found myself emotionally drained by the misery that confronted us daily. “You are a reporter,” she said. “It is different.” But Dufka eventually came to feel that the moral responsibility that accompanied her war reporting was too great. She walked away from her distinguished career at Reuters to work for Human Rights Watch, where she now runs the West Africa division.

“It is a question of, How much do you do?” Feinstein told me. “When you confront these exquisite dilemmas, you also ask yourself: Why did I help this person and not that person?”

Another aggravating factor of moral injury might be believing that your government—one you were brought up to trust—is contributing to the suffering you witness. Many of the journalists reporting from the Mediterranean and the U.S.-Mexico border are working in their native countries. An American reporting on ICE officials separating desperate families at the border may feel doubly responsible—and doubly helpless.

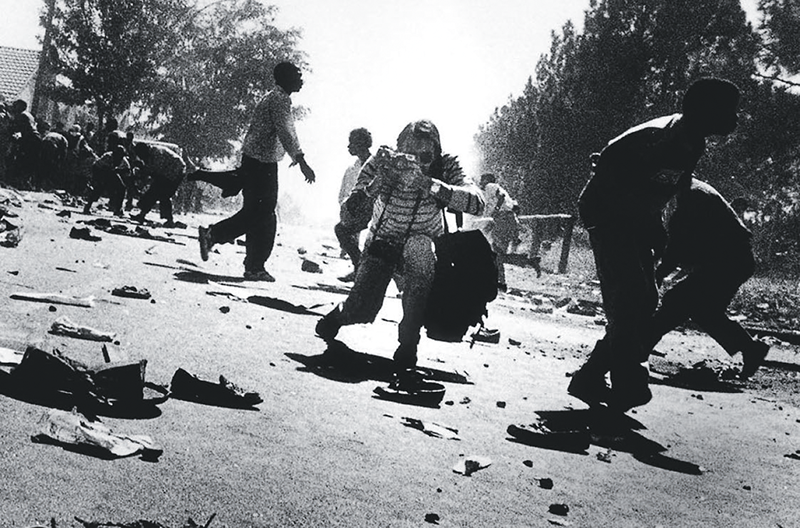

Kevin Carter photographing police firing on a protest in Soweto, Johannesburg, 1993 © Ken Oosterbroek. Courtesy Monica Zwolsman

Of course, moral injury does not affect only war reporters. Soldiers who have witnessed torture, including at Abu Ghraib, have written about their moral injury. Doctors in Syria who were unable to save the lives of thousands of people while working under bombardment have also suffered from it. Survivors of school shootings, prosecutors trying cases that they know will not see justice, and witnesses of police brutality can all experience moral injury. After the COVID-19 pandemic is brought under control, moral injury may be among the problems facing frontline health care workers. These people have risked their lives to save others, but they have been unable to save many others. In some cases, they have had to make decisions about who receives ventilators, who lives and who dies.

Feinstein believes that understanding moral injury will be particularly important in the aftermath of the pandemic, not just because of the number of people who are dying, but because people are separated from their loved ones and unable to properly grieve. “They can develop a whole host of mental difficulties,” he said. He speculated that medical personnel might be especially susceptible. “A position in which you can decide life-or-death issues like this is an acutely uncomfortable one to endure.”

And what about the community at large? Will we all suffer from moral injury given what we have witnessed during the pandemic? Feinstein thinks the predominant emotion will be anxiety, but that people will experience degrees of moral injury. He told me to think of a hierarchy of suffering. Those who have lost people they loved place at the top, and below them are those who lost a business or a chance to celebrate a life milestone such as a wedding or a graduation. “These too will leave their mark,” he said.

Another question is how we, as a society, come to terms with Donald Trump. What will be the long-term effect of feeling moral revulsion toward our president’s behavior?

When I asked Feinstein this, he answered by first quoting FDR: “ ‘The presidency is not merely an administrative office . . . it is preeminently a place of moral leadership.’ This just highlights how far the presidency has fallen over the last eighty years.”

João Silva, a member of the Bang Bang Club, photographing a car bombing in Baghdad, 2003 © Michael Kamber/New York Times/Redux

Feinstein’s moral-injury study is still in its early stages: he has interviewed a new set of reporters and that data is being analyzed. As in 1999, I am a participant. I recently completed my first questionnaire, and in doing so, thought back on my thirty-year career in war zones. I thought of the people I helped, the ones I got out of cities under siege and burning villages, but also of the many I did not.

I often felt like a vulture. But there are ways of protecting oneself. At Yale, where I teach a course about reporting on war and other catastrophes (including pandemics), I begin by introducing my students to the concept of trauma. We simulate working in war zones, but I also teach them that those who spend hours looking at devastated cities through a viewfinder, or interviewing victims of sexual violence during wartime, or even those watching or reading about it from a distance, are susceptible to the evil and darkness that surround conflict.

Is it possible to repair a soul? Feinstein is looking at cognitive behavioral therapy as one potential treatment for moral injury. In CBT, patients seek to identify and alter irrational thought patterns. He believes it might be helpful for war reporters who continue to agonize over moments they can’t change.

“I believe that we are a very resilient species,” Feinstein told me. “We have come through world wars and previous pandemics, and we will of course endure here.”

We have witnessed much tragedy over the past year. It has been historic, vast, overwhelming. Yes, we are resilient. But our souls are scarred.