Bright Power, Dark Peace

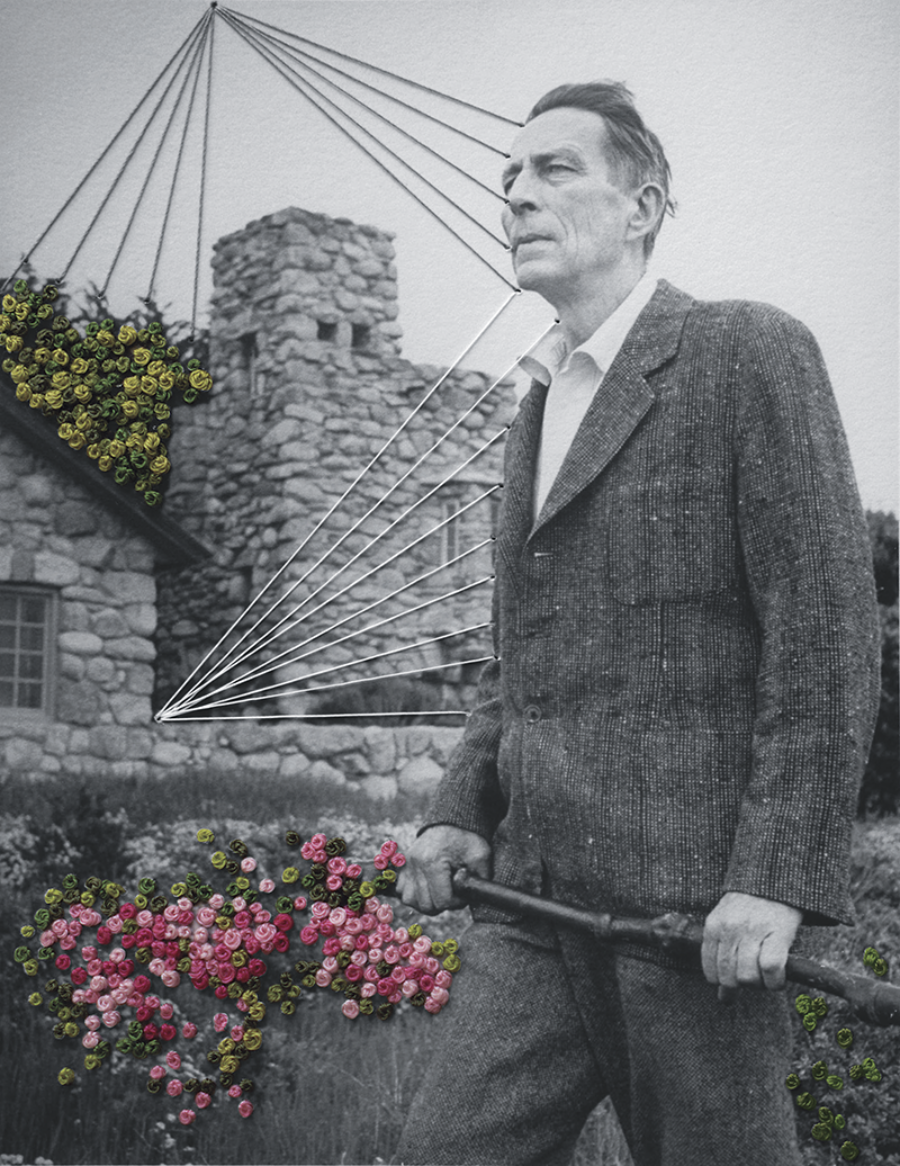

Embroidered photographs by Adriene Hughes for Harper’s Magazine © The artist. Source photograph: Robinson Jeffers, 1948 © Nat Farbman/LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

On a clear October day, I walked to the continent’s edge. I had arrived in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, encased in metal, first in a plane that brought me across the country, then in a rental car that transported me through Silicon Valley and its canyons of mirrored glass. Now I was bipedal again, and making my way along a narrow trail to a granite promontory called Point Lobos. I passed under a grove of ancient cedars, their twisted, wind-haunted limbs rising into an emerald canopy that seemed to float in the sky. A kingfisher darted through the understory as I…