A self-portrait by Francisco Goya, 1810 © akg-images/Nimatallah

The best-known works of the great Spanish artist Francisco Goya do not give the impression of having been created by a particularly sociable man. Describing the nightmarish etchings known as Los Disparates (The Follies), Michel Foucault wrote that Goya depicted “a madness that eats away faces, corrodes features; there are no longer eyes or mouths, but glances shot from nowhere and staring at nothing . . . or screams from black holes.” Goya was drawn to macabre and violent images: two haggard witches sharing a meager broomstick; a man poised with an axe in mid-swing, standing over a pleading soldier atop a pile of corpses; a pair of naked men battling furiously on a barren rock, while fierce leonine creatures emerge from the void to finish off whichever one survives. Even his most important royal commission, a group portrait of King Charles IV and family, is permeated by a sense of despair, with each member of the group seemingly lost in his or her own private thoughts, hardly aware of the others’ presence.

And yet, as Janis A. Tomlinson shows in Goya: A Portrait of the Artist (Princeton University Press, $35), the painter was not the loner that he is sometimes imagined to be. “People enjoyed his company,” she writes, positing that his charm and ability to cultivate patrons in the midst of political upheaval helped him advance over the course of his long, productive life, which spanned eighty-two years, until his death in 1828. Goya maintained a robust correspondence with his friend Martín Zapater, a businessman from his hometown of Zaragoza. The intimacy of some of these letters—Goya referring to Zapater as his “soulmate,” writing that he has prepared a room where they could “live together and sleep,” and enclosing, on more than one occasion, a drawing of a penis—has understandably led scholars to suggest that Goya’s affection was more than platonic. (Tomlinson, however, argues that the very survival of the letters indicates that they couldn’t have been as homoerotic as they now seem.) Goya was also apparently an excellent hunter, and, in the way “a game of golf might today foster relations with clients,” used his hunting expeditions to schmooze with important patrons.

One of the pleasures of Tomlinson’s book lies in encountering the unvarnished details of Goya’s life; her delineation of the artist’s remarkably flexible political allegiances is especially engrossing. But those, like myself, who have long felt an emotional connection to the cryptic melancholy of his late works, which Goya originally frescoed onto the walls of his home (including, among others, A Pilgrimage to San Isidro,Saturn Devouring His Son, and The Dog), will find themselves chastened by her approach. She argues that “the romantic image of Goya, deaf and isolated,” recording his inner pain for his own contemplation, is not based in fact (though he did lose his hearing, possibly due to lead poisoning, in 1793). She suggests instead that the paintings’ “theatricality” and their location in large, central rooms of the house indicate that “Goya painted for an audience, emulating magic lanterns and phantasmagoria that had been offered in Madrid since the 1790s.” Tomlinson cites a contemporary newspaper article that describes an illusionist’s portrayal of a dismemberment as “amusing” to speculate that “Goya’s corpse-devouring maniacal giant” in Saturn “was perhaps far less shocking to his contemporaries than it is to modern viewers.” It’s a reasonable enough supposition from a historian’s perspective, but those who have contemplated Goya’s giant—gnawing, with an expression of agonized helplessness, on a mutilated body—may be unconvinced.

The images of starvation and wanton killing in Goya’s work find echoes in Igifu (Archipelago Books, $16), a newly translated collection by Scholastique Mukasonga, whose stories depict life among displaced Rwandan Tutsis before and after the 1994 genocide. Mukasonga’s gift lies in illustrating the day-to-day reality of a persecuted minority, the calculations that must be made and the humiliations endured. Her novel Our Lady of the Nile, the first of her books to be translated into English, portrays the tensions in a prestigious Rwandan boarding school that, like the one Mukasonga attended, imposed a strict quota on the number of Tutsi students admitted. Though we know the genocide looms, the poignancy of that book comes from its attention to the mundane details of the schoolgirls’ conflicts, the distant rumblings before the storm.

“Ankole 1. Lake Mburo District, Nyabushozi, Western Region, Uganda, 2012,” by Daniel Naudé © The artist. Courtesy Everard Read, Johannesburg

The stories in this collection, translated from the French by Jordan Stump, work in similar ways, narrating individual experiences and resisting the pull toward parable. A community of Tutsi drovers, exiled from their grazing land to the barren Bugesera district, is devastated by the loss of their herd, abandoned when the villagers were forcibly relocated by the government. But they find a new sense of purpose with the arrival of an outsider named Rukorera, who brings with him a throng of cattle. They welcome him and celebrate the survival of his animals. I waited for the development that one might expect in, say, an Isaac Bashevis Singer story: a jealous villager steals a calf, setting off a chain of disastrous events. But no. One night Rukorera simply moves on, heading across the border to Burundi. The community mourns the loss of the cows and continues to struggle along. Eventually, in a zoomed-out denouement, the genocide arrives.

The matter-of-fact psychological probity of Mukasonga’s work is akin to the piercing memoirs of Annie Ernaux and the early novels of Edna O’Brien. She also shares their gift for writing about childhood. In the collection’s title story, the narrator is a young girl who waits with her little sister for their mother to return from work in the sparse fields, hoping she will bring them something to eat. (Igifu means “hunger.”) With visceral immediacy, Mukasonga captures the children’s creeping fear and desperation as they grow weak from starvation. The narrator scrapes sweet-potato crust from the bottom of a pot and vigorously sweeps the house, “hoping to glean a few grains of sorghum or rice that had fallen from my mother’s wooden ladle.” As a last resort, she and her sister feed themselves with the “beautiful, bright-red berries” their mother has forbidden them to eat. This story is as old as humankind, of course, but Mukasonga is not interested in the fruit’s metaphorical potential. “The berries were sweet,” she writes, “not very filling, but at least they weren’t poison.” The wait continues.

“Six Seconds,” by Alfredo Jaar © The artist. Courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

While Mukasonga’s work is a lament for a destroyed world, Wolfgang Koeppen’s Pigeons on the Grass (New Directions, $15.95), first published in German in 1951, and newly translated by Michael Hofmann, is an exercise in outrunning the past. His novel, presented in bursts of action from shifting perspectives, is a modernist tour of Munich over the course of one eventful day in 1948. A woman tries and fails to get an abortion, a German child attempts to scam an American boy out of ten dollars by promising to sell him a stray dog, and a cross section of the city attends an exhibition baseball game, with varying levels of comprehension. The title comes from Gertrude Stein—it is quoted by a visiting, Eliot-like poet, and rejected for its implication that human behavior, like that of “pigeons on the grass,” is random and meaningless—and her protégé Ernest Hemingway is on the minds of numerous characters. But the novel’s clearest literary antecedent is John Dos Passos, particularly the fractal, telegraphic style of his 1925 portrait of disparate city lives, Manhattan Transfer.

It’s little wonder that Koeppen’s vision of Munich feels distinctly cinematic and American. It is brimming with representatives from the newly ascendant superpower: soldiers and tourists, a group of visiting teachers, an accountant from Santa Ana and his memorably obstinate son. They’re all on hand to preside over and bear witness to a new world, the details of which have yet to be entirely worked out. Of great interest to the locals are the black American GIs in the city, particularly Washington Price, a professional baseball player who is romantically involved with Carla, a young German woman who is unhappily pregnant with his child. Price is the book’s most prominent character, and Koeppen is frank about the racism he endures. His love for Carla is placed in poignant counterpoint to the bigotry radiating from her mother and son, and Price’s vision of opening a bar back in the United States, with a sign reading no one unwelcome “in a wreath of colored fairy lights,” is the novel’s refrain, akin to E. M. Forster’s “Only connect.”

Koeppen’s narration is free-flowing, shifting at times, even over the course of a sentence, from a character’s inner thoughts to the verbal static—“Commie Onslaught, Children love Ludens Drops”—of the outside world. The novel’s roving consciousness deliberately blurs the boundaries between characters’ minds, turning Munich into one large, pulsing brain, throwing off brilliant mini-disquisitions on German versus American writers, or the Proustian disappointment one visitor feels in finding the city not quite as ruined as he’d imagined. For a contemporary American reader, there are a few jarring moments that bespeak the author’s ignorance, or worse, of black American life (not least of which is a black character named Odysseus Cotton). It is a dispiriting limitation in the work of a writer who is otherwise often exhilarating and original, and who should be better known in the English-speaking world.

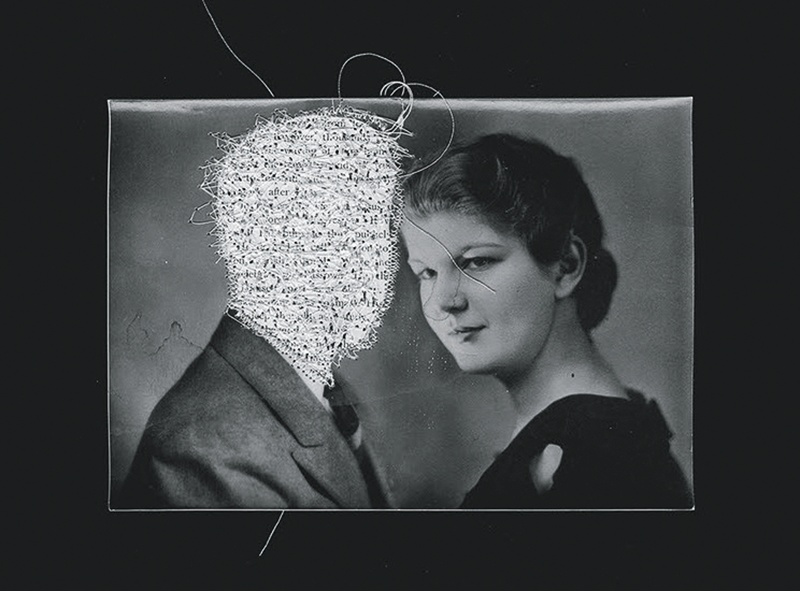

Couple—Sewn, by Liz Steketee, from the series Family Album © The artist. Courtesy Seager Gray Gallery, Mill Valley, California

At one point, Carla laments the distance that has grown between her and her family. She feels herself “lost to her mother, to the respectable circle of other mothers, lost to fatherland and morality, torn away from the parental hearth.” The generational tension between survivors of the Second World War also animates the lives of the characters in Susan Taubes’s first and only novel, Divorcing (NYRB Classics, $16.95), originally published in 1969. The book is idiosyncratically structured, beginning as a work of fragmented autobiographical fiction about a woman’s intellectual and romantic life (prefiguring books such as Sleepless Nights and Speedboat), before settling into a more straightforward account of the history of the narrator’s Jewish family in Budapest and the trauma inflicted by the war.

The protagonist, Sophie Blind, is desperately unhappy in her marriage to Ezra Blind, an esteemed scholar who conducts constant extramarital affairs. (As the book opens, she has also discovered the joys and complications of infidelity.) Sophie, like her husband, is an academic, and working on a novel. She thinks through her well-worn situation in brilliant, knotty patches:

Two people, a man and woman, living together was intrinsically right; and to have established this as a settled matter once and for all so you didn’t waste your time looking around or endlessly analyzing your feelings—this was the virtue of marriage. Thus Sophie found herself, while still frowning on marriage in principle, enjoying it in practice, enjoying the sheer twoness that endured independent of moods, likes and dislikes, that did not need reasons and that wouldn’t be destroyed by reasons.

Born in Budapest, Sophie fled the country as a child with her father in 1939, leaving her mother, who had taken up with another man, behind. When her mother eventually moves to America, an emotional barrier remains between them, forged by their time apart. Meanwhile, her father, a Freudian analyst, is disappointed by Sophie’s lack of interest in his vocation. But her observations of him occasion some of the novel’s sharpest insights. A man of complex contradictions, he rejects religious observance and embraces the gospel of psychoanalysis, yet is still enmeshed in the Jewish community. She watches him at a Passover ceremony at her grandmother’s house:

He chants swaying back and forth, the expression on his face not like when he is just Papi or imitating someone else and ridiculing at the same time. . . . Now he is really a Jew praying, now he is making fun of a Jew praying. It’s hard to tell, perhaps there isn’t that much of a difference; perhaps that’s how a Jew was meant to be praying.

Taubes committed suicide shortly after the book was published to withering reviews; Hugh Kenner’s in the New York Times stands out still for its misogyny and willful incomprehension. (It opens with the sentence, “This contains mild rewards once you fight down the rising gorge that’s coupled to your Sontag-detector.”) Knowing how her life ended makes reading the novel at times unbearably sad. “Books were better than dreams or life,” she writes. “A book ended not like life, abruptly; not like a dream, with a clumsy struggle and sense of deception; but gracefully and knowingly, preparing you for the final period.” I wish, in this case, it were less final. Though Divorcing was her only published novel, her philosophical writing, correspondence, and (one can hope) unpublished fiction await rediscovery. In dark times, it is good to have things to look forward to.