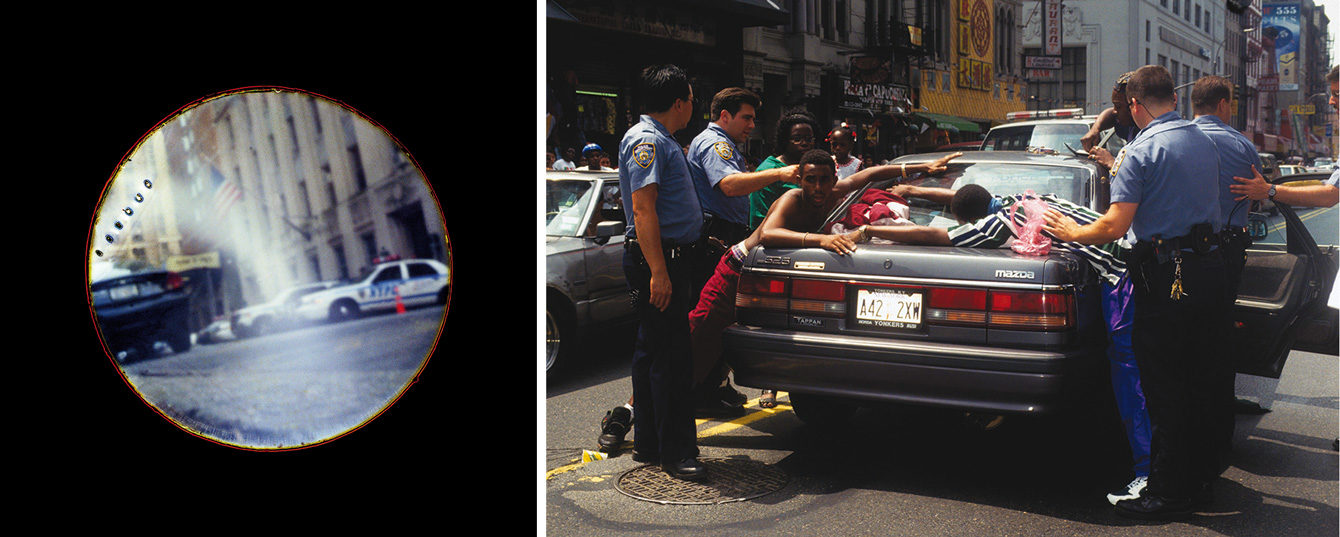

Police officers in New York City, 1995 © Glasshouse Images/Alamy

When I began working as a public defender in Manhattan, I was met mostly with pity. It was the mid-Nineties, and whatever was in the air, it wasn’t nuance. The city was in the process of reimagining the very concept of crime and, by extension, who should be subject to incarceration. Under orders from the mayor, the police took conduct that New Yorkers had grudgingly borne for years as symptoms of inequality—stop at a red light and someone emerges to clean your windshield in the hopes of a quarter, visit a fast-food restaurant and someone opens the door with their palm out—and criminalized it. This was broken-windows policing, and you were assured that it was not targeting any particular group, just following the science. It was theoretical and innovative and evidence-based, and to object was equivalent to insulting victims. The euphemistic target was “quality of life” offenses, but to us interested observers, well, we had eyes and could see what our clients almost always looked like.

In these cases, the damage was mostly limited to misdemeanor prosecutions. Just above them, though, was the toxicity of the long and wholly undeserved sentences with which America has packed its prisons. At the height of this era, I picked up the case of Huascar Jimenez*. I can kind of remember his face, but what I doubt I’ll ever forget is two numbers: seven and fourteen.

The case was fairly standard, if concerted injustice can ever be so, but with a twist. I was three or four years in by then, so I was well aware that the police seemed to respond to emergencies far less often than they conducted quasi-military operations featuring what I’m sure they thought was badass nomenclature like Special Ops and Tactical Narcotics Team (TNT). The two most common operations were buy-and-busts and observation sales. In a buy-and-bust, an undercover officer pretends to be a dope-sick buyer. He hands a seller about ten dollars in “prerecorded buy money”—currency that has been photocopied and logged—in exchange for a small amount of crack or heroin. The buyer then radios a description of the seller and anyone else they want to involve to his team, who make arrests, hoping to recover the buy money and the stash of drugs. Observation sales proceed differently. The police set up on a roof and watch the street below with binoculars. If they see any suspicious hand-to-hand activity, they relay a description of the relevant individuals, leading to arrests where they hope to recover narcotics from the buyer and money and “matching” narcotics from the seller.

The twist was that Huascar’s arrest fell into neither of these categories. In his case, a Special Narcotics Enforcement Unit was on its way to set up an observation post when officers looked to their left and saw him plying his trade. A lot of people like a lot of heroin. That’s where Huascar and the many others like him come in. He sold a product with insatiable demand. This meant huge profits, but not for him. See, Huascar didn’t just sell to people who loved heroin—he was one of them. That’s what got him into the game in the first place, not any profit motive. And this was no coincidence. Street sellers were mostly functional addicts or teenagers. They took all the risk for little to no reward. The addicts were compensated with minimal product and the teens with street cachet and a monetary pittance. With rare exceptions, these sellers and their buyers were the only ones being arrested for drug offenses. The police knew this. The prosecutors knew. So did the judges.

Huascar was working for product, and as he sold openly on the sidewalk, feet away from the NYPD, he was grabbed while holding nine decks of heroin, street value about $90 at the time. He was a veteran seller, with a couple of drug convictions to his name and palpable apathy when I met him at his arraignment. He knew the legal process for cases like his as well as I did. Charged with possession with intent to sell—the buyer wasn’t arrested—he was facing a minimum sentence of four and a half to nine years in prison. He had ample company, so much that a court routine had emerged to deal with the volume. At the first court appearance following an indictment, the prosecutor would make a onetime offer of a sentence less than the minimum. Anyone rejecting this offer was essentially committing either to a later plea bargain with a harsher penalty or to a trial, and few had the stomach for that. But Huascar rejected the offer and just kept on rejecting until we arrived at trial.

These rejections were less protestations of innocence and more defiance born of chronic defeat. That was fine with me; I rather enjoyed it. I viewed everything through the prism of a trial, and my experience of trials up to that point suggested that conducting one here would be fascinating. Any clinical assessment would have concluded that the prosecutor had a big advantage, but I wasn’t all that into those kinds of assessments. Huascar wanted a trial, and it was his decision. Besides, there was an odd element in his case in that neither of the classic types of police drug operations had led to his arrest. Oddness is almost always helpful to the defense—in the right hands, it can pierce with doubt the prosecutors’ projection of uncontroversial routine and concomitant guilt. Well, as I predicted, the trial was fascinating, but only in the sense that every trial is. And there was nothing fascinating about the end. When Huascar was sentenced to seven to fourteen years in state prison, those numbers singed into my mind, where—look at the evidence—they remain today.

I had lost trials before, but not like this. I was reeling, both outraged and embarrassed. It was maybe time to stop. I had options. I could stop practicing law, or do so elsewhere, and just absent myself from this mess. Because there was a sense in which, as a public defender, I was part of this vicious machine. Certainly a significant portion of our clients felt that way. I could remove any doubt about my personal responsibility by withdrawing. Or I could keep going and become so good at this trial thing I would never have to live that again. Whatever the reason, I kept going.

Left: “Hidden (Camera Obscura), Midtown North Precinct/306 West 54th Street, 2008,” by Alain Declercq © ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris. Right: NYPD officers conducting a stop-and-frisk search in Lower Manhattan, 1994 © Stacy Walsh Rosenstock/Alamy

The great machine rolled on, unaffected by any personal crises of mine. Even the victories began to feel Sisyphean, or at least Pyrrhic. I represented twenty-year-old Taurean Bell, who was arrested following the execution of a no-knock narcotics search warrant. He had an easy smile that expanded considerably when the jury found him not guilty. Even I, at the time probably the least social work–oriented public defender ever created, felt the need to go into lecture mode before saying goodbye. You’re a target, search warrants prove that, you should behave as such. There has to be a better way to make a living, one that doesn’t have the potential to lock you up and brand you a felon for the rest of your life. He nodded in the universal sign for You, in conjunction with life experience, have shown me the light. Two days later, I was in arraignments. Anyone arrested in New York is entitled to see a judge within twenty-four hours for their arraignment, when they formally enter a plea and a judge decides their bail status. There’s a bench to the side of the judge where prisoners sit just before their court appearances. I saw a familiar face and stared. Then ducked away before Taurean could see me.

That’s how relentless it was. We were standing in a river trying to stem the current with our hands. An immitigable flow of drug arrests, with search warrants and confidential informants and buy money and stashes and drug-prone locations and undercover officers risking their lives to round up addicts. And guilty pleas, my God, the guilty pleas. If any conviction is a loss for a public defender, then the truth is that we were all getting slaughtered. It was a slaughter that made a diaspora: black and brown people torn from their homes and thrown into cages.

Conspicuously absent from all this, you’ll note, is any violence. You can define crime however you wish, push or pull it to suit your needs, but you cannot escape the fact that there’s a subset of the concept that isn’t easily manipulated. With violent crime, there’s an actual victim, a victim who is motivated to report the crime and who tends to take an interest in the status of the investigation and prosecution. Contrast that with the slew of American criminal cases that involve mutually motivated parties voluntarily exchanging money for substances, a public-health issue that somehow transmuted into an explicitly declared war. The bad news for those who wish to see our prisons and jails strained to capacity is that violent crime in this country is on a decades-long and precipitous decline. Precipitous as in the violent crime rate dropped nearly 50 percent between 1990 and 2018. And this decline shows every sign of being unrelated to how many people our society chooses to incarcerate for how long. So if the police are here to keep us safe, but we keep getting safer and safer irrespective of their conduct, then modern policing, with its characteristic overwhelming show of force, begins to look like a cure in search of a disease.

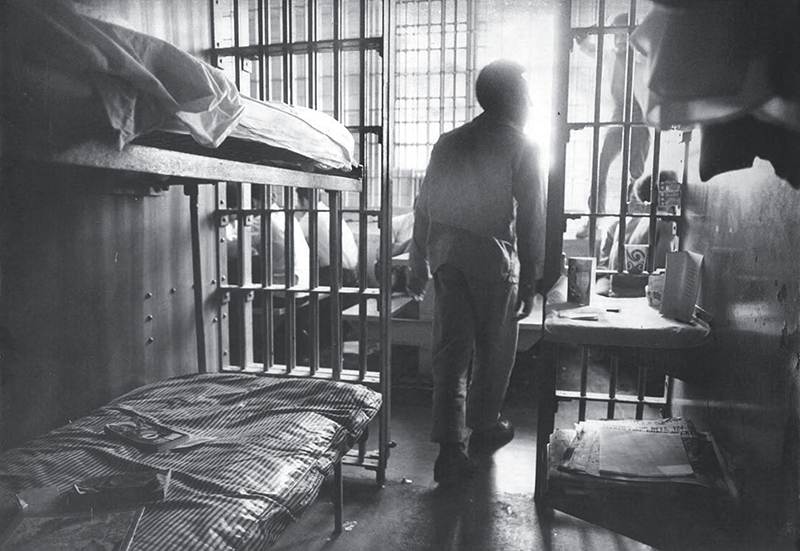

The Manhattan House of Detention (the Tombs), 1971 © Librado Romero/New York Times/Redux

Then, around ten years ago, progress. Books like Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow led the way, and suddenly the words “mass incarceration” acquired meaning outside public defenders’ offices. The Rockefeller drug laws that had disappeared people like Huascar Jimenez were amended to better reflect proportionality. An underappreciated aspect of the system, jury pools, also began to change, imperceptibly at first, then undeniably. The voir dire, or jury selection, is where any criminal-defense attorney worth anything will spend time educating the potential jurors, twelve of whom will later decide their client’s fate. But whereas before I had been fixated on ferreting out jurors whose antidrug sentiments would make them unfair to my client, now it was the prosecutors obviously concerned that too many potential jurors were in favor of legalization. True change of the best kind: hearts, minds, and laws.

Of course, greater fairness in this limited area did not extend elsewhere. New York remained, until 2017, one of only two states to fix the threshold of criminal responsibility at the shockingly low age of sixteen. Its cash-bail system linked our clients’ constitutional rights to their ability to pay. Discovery rules that were among the worst in the nation allowed prosecutors to purposely conceal evidence until the last moment. So a New York City public defender could easily find herself defending at trial a seventeen-year-old facing imprisonment and a lifelong felony record, incarcerated only because he couldn’t afford $2,000 cash bail, and watch the prosecutor drop hundreds of pages of police reports on her just before the jury walks in. I’ve seen it done.

Judges could remedy much of this, but most were skilled at seeing and hearing no evil. In another trial I’ll likely never forget, I secured an audiotape proving conclusively that the prosecution’s main witness had just committed perjury. As I prepared to play the tape for the jury and enjoy my glorious Perry Mason moment, the judge informed me that that wouldn’t be happening, because I had surprised the prosecutor. Never mind that my client was charged with a violent felony carrying a mandatory prison sentence and that everyone agreed that the complainant had just lied—I was somehow the bad guy for doing what prosecutors did as a matter of course. Lots of vitriol followed, ending only when the prosecutor’s supervisor interjected sanity by dismissing the felony charges. A week later, I ran into one of the jurors. She wanted to know why the case had ended so abruptly. I told her in general terms, and she had no real reaction beyond wondering whether I could represent her in a dispute with her landlord. I said I was busy.

We operated under this system for years, because if you wait for a level playing field, they just go on without you. The next great change was societal, not judicial. The widespread recording of American life, and especially its policing, has been revelatory. Early on in our age of ubiquitous surveillance, I had an unsettling experience. Only the generalities remain, but they haunt me enough. I was representing a man charged with the armed robbery of a stranger. He was adamant that he hadn’t done it—not uncommon—but he was also full of useful details regarding where he was at the time. Pretty quickly I was able to obtain video surveillance showing that he was telling the truth. The prosecutor dismissed the case, and I patted myself on the back. But less than a week later, I had a new client facing the same charge and making the same claim, again with useful details. And again I found video proof that completely exonerated my client. Securing incontrovertible exculpatory evidence and having the charges dismissed twice so close in time felt unreal. I was relieved for the clients and I guess proud of my work, but it was also true that the earth shifted under my feet. Both clients had been charged with violent felonies carrying mandatory prison sentences. What if there had been no video? What if I’d negligently failed to obtain it? Across decades and thousands of cases, is it possible I’ve mishandled a human life? Is an unequivocally innocent client of mine serving time in state prison? I used to be diligent and intense out of duty and makeup. Now I’m diligent and intense out of fear.

NYPD surveillance screens, 2011 © Christopher Anderson/Magnum Photos

No matter the level of diligence, there’s an eternal resource gap to overcome. Fyodor Dostoevsky supposedly said that “the degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” I first remember seeing this quote not in a literary or political text but in the visitors’ entrance area at the Manhattan Detention Complex, or the Tombs. The Tombs is a very famous jail. It opened in 1838 and is scheduled to close never. Melville’s Bartleby went there to die, as have a great number of my clients, if not physically then at least spiritually. The complex is one of the most hideous places on earth, so I’m not sure what the quote is intended to convey. Intent aside, the claim is weak. Maybe it’s the environment where I first encountered it, or the fact that Dostoevsky never actually said it, but I’ve entered a great many jails and prisons and I think greater truth can be located elsewhere. Let me propose a different barometer, one based on how society chooses to spend money.

A little more than a mile from the Tombs, there’s a bull. An unofficial Wall Street mascot, the sculpture is called Charging Bull; you’ve seen it. Created by a fan in the aftermath of the 1987 stock market crash, it was designed to remind traders that they must be strong even when things are very bad. The year it was installed, the Dow was at 2,700; today it’s around 27,000, despite a true unemployment rate estimated to be close to 20 percent. As protests spread through New York City this summer, the bull disappeared. Well, he stayed right where he always is. But suddenly he was covered in a blue tarp, fenced off, and guarded by police officers. Bull or no bull, the city, like the world, watches Wall Street closely because the scraps dropped there decide the scope of critical social services. But while offices like mine sweat the yearly undulations of city revenue and the existential threat of cuts, there’s been one recipient that has never had to worry.

Last fiscal year, the NYPD had a budget of $5.6 billion. This was more than the budgets of Montana, Delaware, or South Dakota—not their police departments, the entire states. The NYPD employs 36,000 police officers and about 19,000 other personnel. They have money to burn, and they burn it on the latest surveillance weaponry, which they disproportionately wield against communities of color. They have an entire section devoted to facial-recognition technology, despite numerous studies establishing that such technology puts people of color at greater risk of error than the rest of the population. They monitor social media and claim to have created reliable but inaccessible-to-outside-parties “gang databases” that prosecutors rely on in court. They use license-plate readers and devices called stingrays that trick cell phones into connecting to them. They use something called ShotSpotter that claims to pinpoint gunshots, and they drive around in vans that use “Z backscatter” to see inside cars and through walls. They have their own lab that produces findings that uncannily support the prosecutions they initiate. And all this is employed using something like the honor system. There is no significant oversight, and repeated attempts by organizations like mine to force the department to disclose precisely what technology it has and how it is used only recently got any traction. And this secrecy extends even to mundane policing. Until very recently, the personnel records of NYPD officers, including complaints and findings of misconduct, were shielded from the public by a “civil rights” law. Meanwhile, in fiscal year 2018, New York City paid approximately $230 million to settle lawsuits filed against the department.

The public-defender offices battling this behemoth had to change, and they did. Winning individual skirmishes would no longer suffice; we had to change the rules of engagement. We had litigation, but litigation is a fragile tool. For years we would go into court armed with clear truth only to watch police officers insult the idea while judges pretended to believe them—a practice so common that the word “testilying” was invented. What was needed was major legal reform, and now every big public-defender office in the country understands that this is part of its mission. In New York, we work with grassroots organizations that are led or advised by formerly incarcerated people. These organizations don’t just cite the Constitution and legal precedent—they tap into community anger. And this anger, more than anything, has changed the rules. The age of criminal responsibility was raised to eighteen. Drug-treatment and mental-health-treatment sentences were expanded. Stop-and-frisk and prosecutions for carrying gravity knives (a category of common folding blades whose definition was notoriously subjective) died well-deserved deaths after it became apparent that they had become tools of racial discrimination.

Then, this January, we saw unprecedented, seismic change. Genuine bail reform greatly reduced the number of cases where cash bail was permissible. New York’s retrograde discovery statute was replaced by maybe the most robust one in the nation. In June, after decades of bitter dispute, the law blocking access to records of police misconduct was repealed. Much remains to be done, but it’s a start. A template for the nation to follow: community anger paired with law degrees to cow legislators afraid of voters.

And if you’re angry at America’s policing and legal system, right now you may have more company than ever before. In June, I attended a nationwide event billed as Black Lives Matter to Public Defenders. Public defenders from across the country livestreamed local protests in a mixture of solidarity and outrage. The turnout was strong and the signage intense. Reading the posters was like watching a real-time struggle to find solutions or at least sense. Some called for government action: demilitarize police, our communities are not enemy soil. Others read like general mission statements, declaring that we who believe in justice cannot rest. Still others, while offering sound legal advice (don’t talk to cops), also had a pleasing middle school quality of organized punitive ostracism. Ultimately, the most moving language didn’t pretend to know, it just asked: how many black people have to die?

As the protests in New York swelled, the NYPD and the Manhattan DA’s office defaulted to their usual response: arrests and alarmist rhetoric. Armed with a silly curfew that was withdrawn when public defenders and civil-liberties groups threatened legal action, the NYPD trapped a sea of protesters near the Brooklyn Bridge, then swung batons and created chaos with the tactic called kettling. Protests were called “riots” and protesters “looters” because this rhetoric works. The alarmism had begun earlier, in January, when the state’s widespread reforms started to go into effect. The diminution of bail as a tool of control, prosecutors and the police said, was making them powerless to protect residents from repeat violent offenders, and the new openness regarding police reports and other information was endangering the lives of civilian witnesses. These were the same arguments rejected during the many years the legislation was being considered. There was no empirical support, either in local data or in the experiences of other states. But on April 3, in the middle of a global pandemic that had effectively closed the state, as the city’s defenders scrambled to get as many clients as possible off Rikers Island and out of the Tombs, New York still found a way to roll back many of the reforms that had been enacted just three months earlier. More poor people will be jailed while presumed innocent, and more evidence against them will be concealed.

In July, I appeared virtually in Manhattan Supreme Court on behalf of my client William Ross. I met William when he was a teenager, and today he’s not. I’ve known him this long because he keeps getting arrested. It’s frustrating, but it takes a lot more than that to alienate me. Especially if you’re as soft-spoken and unintentionally funny as William.

The court appearance, like everything lately, had elements of the surreal. Its purpose was to determine whether there was any way to dispose of the case via plea bargain, the true cornerstone of our criminal-justice edifice. From behind a black mask on a computer screen, William listened as I said that we didn’t have to turn another life into a dead number written on the immense roll of the confined. That if he pleaded guilty, he should receive a sentence of probation, no jail time. There were nods of assent. We all had read the same literature, knew the same figures. I felt momentum, even started to work myself up a bit. Then the case was adjourned for trial.