Perfect Storm

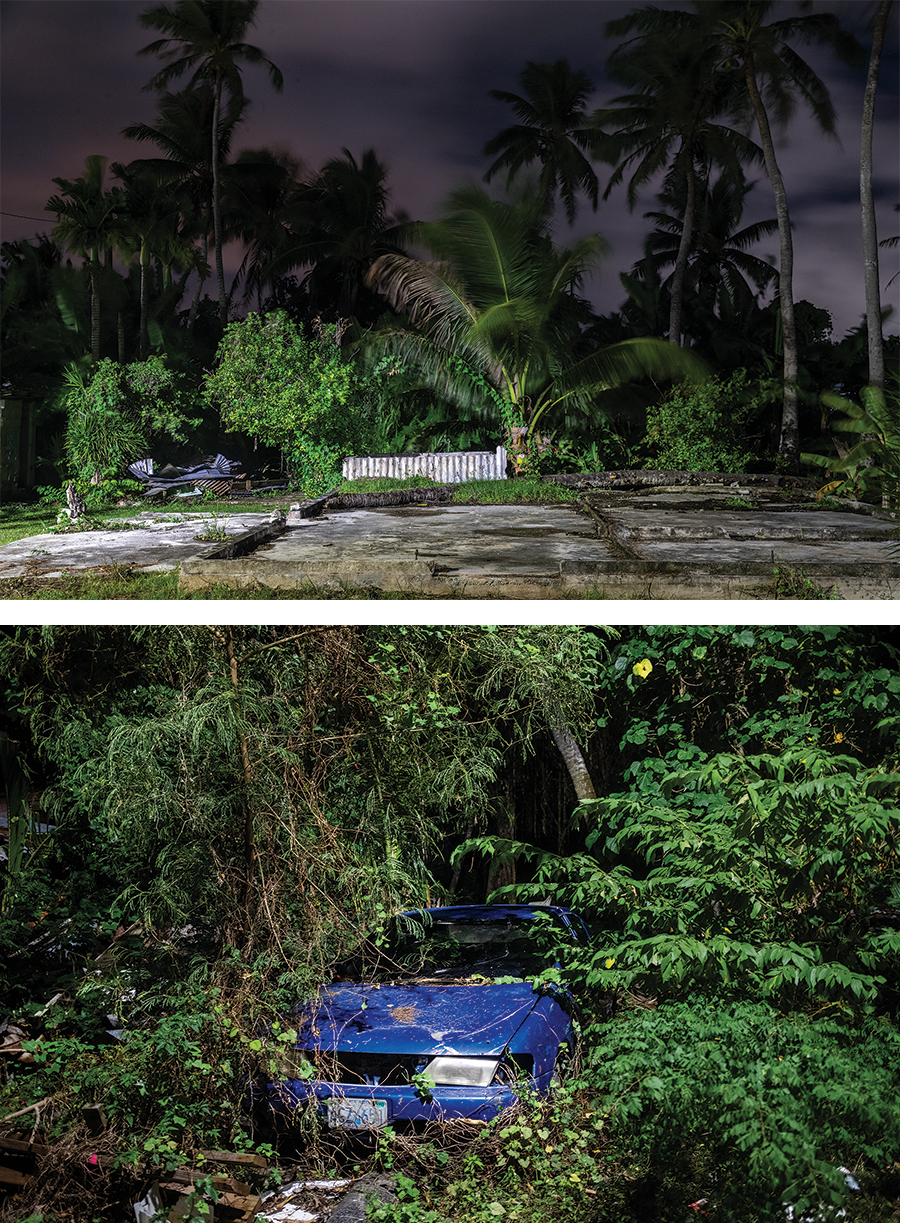

Photographs from Saipan, February 2020, and Las Vegas, July 2020, by Victor J. Blue for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

The spiders gave away the scale of what was coming. Had they remained in their webs, Velma Del Rosario would have stayed home, too. It was October 24, 2018, late in the season for a storm. Velma had initially believed it would be small, a “banana typhoon”—the local term for the spells of rain and wind that wash over the Northern Mariana Islands every year, snapping the banana trees. Super typhoons were rarer, arriving only once a decade.

Earlier that afternoon, Velma had gone about her usual preparations. At four o’clock, she left the Veterans Affairs office where she worked and drove five miles south to her home in the village of Finasisu, stopping along the way to pick up her husband, Henry, from his job at the local utility, and their youngest child, Analina, whom Velma’s sister watched after school. At a grocery store, they bought bread, eggs, canned goods, and Vienna sausage—“that nasty stuff” Velma secretly loved—and then returned to their house, where they filled a five-gallon drum and an ice chest with water.

Finasisu is in the south of Saipan, the largest of fourteen atolls that form the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, a U.S. territory six thousand miles from the mainland. In 1944, the United States captured the islands from Japan in one of the Pacific theater’s costliest battles. Thousands of Japanese and American soldiers died, as did more than nine hundred Chamorro and Carolinian people, who are indigenous to the islands. Velma’s family is Chamorro. Her grandmother Ana lost her husband and three of her children in the siege, among them a baby struck by shrapnel as Ana ran with him in her arms. After the war, Ana remarried and moved to a plot of land belonging to her second husband, where she planted mango, breadfruit, tangerine, and coconut trees. It was here that Ana raised Velma and, later, that Velma and Henry built their own house, clearing the land with machetes and constructing the walls with cement bricks.

Velma decided that they would spend the storm in the bathroom, the most secure part of the house. Three years earlier, the last super typhoon to ravage the island, Soudelor, had damaged the structure, and Velma had received a $15,000 loan from the Small Business Administration to make repairs. She replaced the vinyl flooring with ceramic tile, installed rebar over the windows, and reinforced the tin roof. Only four months had passed since she’d finished the repairs. When her mother, Dolores, called that evening to ask where they would ride out the storm, Velma assured her that they were safe at home.

At dusk, the wind picked up and rain began to fall. Velma was taking her time. She sat on the couch, scrolling through her Facebook news feed. Her friends were posting images from radar apps—smartphones made every islander a weather expert—of a thickening mass trolling across the northwest Pacific. Velma’s twenty-three-year-old daughter, Christylynn, called; she had taken refuge in a hotel with her boyfriend. She urged Velma to go to Dolores’s house, which was fifteen minutes away in a nearby village. That house was safer, as it was made entirely of concrete. But Velma repeated that she would be fine at the family compound.

At eight o’clock that evening, Velma stepped outside. That was when she noticed the spiders—or, rather, their absence. The webs they had spun in the eaves of the house were gone. Her grandmother had always said that if the spiders fled, a super typhoon was coming. Velma called to Henry, “We’re getting out of here.”

When they arrived at Dolores’s house an hour later, rain was falling harder. They lingered in the car to hear a priest say the rosary on the radio, and then they settled into her mother’s bedroom, which was separated from the main house by a breezeway. Dolores and Analina shared a twin bed, while Velma and Henry slept on a queen. Just after midnight, Velma woke. The door had blown open, and rain was pouring in. Gusts had shattered the windows in the main house, and now her brother and his children came running through the breezeway into Dolores’s bedroom, where they huddled on the beds. The room shook; the wind roared; they heard the percussion of flying tin. Analina remained asleep, but when the bedroom windows began to buckle, Velma woke her. “You have to pray,” she instructed Analina and her brother’s children. “Because you are kids, and God hears your prayers.”

Typhoon Yutu was stronger than Hurricanes Katrina and Maria, stronger than any storm that had struck U.S. soil since 1935. Islanders who survived the typhoon will tell you they had never felt anything like it before. They will describe the sound: “An eerie sound.” “Not like a whistle-whistle, but a harsh whistle.” “It sounded like somebody crying.” “It sounded like a war.” “Like everything was breaking.” They will describe how the wind sheared the roofs off houses and schools where they had sought shelter; how it broke typhoon-proof glass and toppled concrete walls; how it entered through windows and whipped their belongings into cyclones; how one man survived by lashing himself to his toilet bowl as the rest of his house lifted into the air around him.

Christylynn Del Rosario did not sleep that night. She lay on the hotel bed with her boyfriend, who slept with his back to the window. She had begged him to let her lie in his place—that way, if the glass broke, it would be her body that took the shards—but he refused. Through the window she could see Garapan, the island’s main town, and the Imperial Palace Saipan, a white-and-gold casino that had been under construction for years. A crane perched on the casino’s roof spun like a broken weather vane.

At daybreak, Velma called. She, Henry, and Analina were safe at Dolores’s house. Christylynn felt a surge of relief—it was the first typhoon she had spent apart from her mother and father—and then her relief faded to dread. It had been only three years since Typhoon Soudelor struck the island. That was the worst damage Christylynn could remember. Her family had gone without power and water for months, their lives reduced to lines: Lines for water. For laundry. For gas. Once, she had waited in a gas line for seven hours—so long that some people ran out of fuel and had to push their cars to the pump.

She knew already from the sound of the storm that the aftermath of Typhoon Yutu could be even worse. Her cousin Doris, who had spent the night in a room across the hall, was on her way to their family compound, texting videos to Christylynn as she drove. Velma and Henry had already tried to reach it, but downed power lines blocked their way. Christylynn followed Doris, making it almost to the compound’s entrance, where a tree had fallen across the road. She got out to walk. The mess of debris disoriented her. She didn’t recognize their house at first. Then she dialed Velma. “Mom,” she said. “Everything is gone.”

Christylynn Del Rosario in her family’s house

Few pieces of U.S. territory are as perilously positioned as the Northern Mariana Islands. The region of the ocean where they sit is called typhoon alley, a vast area of the northwest Pacific that breeds more tropical cyclones than anywhere else on Earth. According to a study in Nature Geoscience, the number of Category 4 and 5 typhoons in the northwest Pacific has more than doubled over the past forty years, and storms will continue to grow stronger as climate change warms the oceans. Typhoon Haiyan, among the deadliest storms ever recorded, killed 6,300 people and displaced four million more when it hit the Philippines in 2013.

The commonwealth’s remote location makes it a difficult place to rebuild. Materials are hard to come by; the workforce is small; shipping is slow and expensive; and after centuries of occupation—by Spain, Germany, Japan, and the United States—the economy is far from self-sustaining. After a typhoon hits, the commonwealth relies for the most part on the Federal Emergency Management Agency to fund and coordinate recovery efforts.

When Typhoon Yutu struck in October 2018, ninety FEMA personnel were already stationed on Saipan in response to a typhoon that had plowed into Rota, one of the other atolls, forty-three days earlier. As soon as Yutu passed, first responders deployed across the islands, tending to survivors. David Gervino, a FEMA spokesman at the time, called it “a testament to islanders’ resilience,” and to their fluency in typhoons, that only one person died in the storm. But Yutu had taken a greater material toll than the commonwealth had ever seen. Four thousand homes were destroyed, and over the following weeks, almost 10,000 households applied to FEMA for financial assistance—a significant number, considering that the population of the commonwealth is only 54,000. For these islanders, the storm was a clear warning of what the future could hold, and the first time many would consider leaving the Northern Marianas altogether.

There is no doubt that climate change will bring about a profound reordering of the map of human life. Already, entire towns in the United States have begun to pick up and move—Newtok in Alaska, Tangier Island in the Chesapeake Bay, Pecan Acres in Louisiana. While these wholesale desertions have so far been rare, a dispersed but far more extensive pattern of climate migration has quietly been forming: As storms strengthen, more and more people are being forced to decide whether their communities are worth rebuilding, given the mounting risks, or whether they should abandon them completely. How quickly the world’s population shifts, and what shape the new map takes, will come down to millions of these individual choices, made by people like Velma Del Rosario. After Typhoon Yutu, Velma and other residents of Saipan all found themselves asking the same question: Have I had enough?

Christylynn in the tent she and her boyfriend shared after Typhoon Yutu

Velma could hardly bear to look outside in the days following the storm. When she and Henry finally made it to their house, she sat on the couch and wept. The roof was gone; the doors had been yanked from their hinges; the floors were covered in dirt and broken glass. Everything had been destroyed, save for a shrine of ceramic saints, a charcoal portrait of Velma and Henry on their wedding day, and a photograph of their eldest child, Christopher, who died in a motorcycle accident in 2014. They had no insurance, no mortgage. Only people of Chamorro and Carolinian descent can own land in the commonwealth, so banks are loath to offer loans, as they’re limited in their ability to repossess land in case of default. Like most islanders, Velma and Henry had built their house in stages, managing with what money they had—until Typhoon Soudelor, when they received the SBA loan, which they had only just begun to pay back.

Henry suggested they focus on one room at a time. They carried their mattress, heavy with rainwater, outside to let it dry in the sun. Then they went to a hardware store, the shelves almost bare, and bought the last tarp in stock, stretching it over half the living room. Once their mattress was dry, they dragged it back inside and set it up under the tarp. They wiped everything with Clorox, though Velma was careful not to tidy up too much. She had made that mistake after Soudelor: by the time FEMA officials inspected her house, she had already discarded her damaged belongings and received no assistance for what she had lost. Now she cleaned just the area where they would sleep and left almost everything else untouched. Four days after the storm, she went to her office, one of only a few buildings on the island that had power. She logged on to FEMA.gov and applied for disaster assistance.

Weeks passed, and no inspector came. Every time Velma visited the FEMA website, she saw the same message: the agency had received her application and would be sending an inspector soon. FEMA was still in the early stages of its emergency response, focusing on providing water, food, and medical care to survivors. But inspectors were also facing a challenge specific to the commonwealth as they set about cataloguing the storm’s damage: Houses in the Northern Mariana Islands often don’t have addresses, nor do owners pay property taxes, and one family compound can contain multiple buildings. To determine who qualified for assistance, inspectors had to travel to each home and assess the damage, often on foot.

While Velma and Henry waited, they fell into a new routine. Since they no longer had power at home, they left work early each afternoon to cook and clean before the sun went down. In less than a week, they had run out of the water they’d collected prior to the storm. So, on their way home from work, they drove to the nearest well and waited in line to refill their five-gallon drum. Back at home, they built a fire outside to cook rice. By the time they finished eating, it was usually dark, and they prepared for bed. The typhoon, when it fled the island, had taken the wind with it, and now mosquitoes congregated in the hot stillness. Henry burned coconut husks to ward them off, wafting the smoke around the house. He had a fan but no fresh batteries to run it, since prices had skyrocketed after the storm. Henry found a solution to this, too: In the mornings, before leaving for work, he placed the batteries on a sheet of tin, positive ends pointing toward the sun. Each night, the refreshed batteries lasted six hours. Once they ran out, the Del Rosarios would wake up drenched in sweat, or sometimes rain, which pooled in the tarp above the living room and poured onto the floor. Velma, Henry, Christylynn, and Analina would rise to sweep the water out with brooms.

Velma grew wearier each day. Years earlier, after her son died, her body had acquired a sharp ache, which worsened after Typhoon Soudelor. She had gone to the doctor, but a diagnosis eluded her. Now the pain became unbearable; some days she could hardly walk. Mold blossomed in the house, emitting a terrible odor. It seemed to Velma that no one had time to tend to anything but their own survival. Christylynn worked long days as a TSA agent at the airport, and in the rare hours she spent at home, she seemed distant and depressed.

The person with whom Velma spoke most frequently in the days after the storm was her cousin Junie Tudela. Junie lived on the mainland, near Seattle, and had messaged Velma to make sure that she was all right. Now they chatted on WhatsApp every morning at seven. Whenever Velma described her hardships, her worsening health, Junie suggested that she come to the mainland to stay. On a video call, Junie took Velma and Henry on a virtual tour of her home. When she came to the spare bedroom, she showed them how she had already made up the bed. Velma laughed. Seeing the bed filled her with sudden longing, but Velma said she couldn’t leave Saipan. Besides, she told Junie, “I don’t want to impose that burden on you guys.”

Finally, four weeks after the storm, an inspector from FEMA arrived at the compound. He told Velma that the house was “totally damaged” and that she could receive a small grant from FEMA to make repairs. Velma suspected the money wouldn’t go very far. Her other option was to take out another SBA loan. FEMA’s assessment of the damage, in combination with Velma and Henry’s total income—$38,000—qualified them for a loan of up to $70,000.

Velma considered her choice. She could take the SBA loan, adding it to the $13,000 she still owed on her prior loan, but she would be seventy-three by the time she paid it all off; Henry would be in his nineties. Would they live that long, she wondered? Certainly, they couldn’t work that long. Even if they accepted a loan, how long would it be until their house was livable again? Hardware stores were empty; contractors were expensive and overbooked. Soon, the commonwealth would enact austerity measures, cutting Velma’s hours and pay. She and Henry were less capable than they once had been of doing the work themselves. And how much time did they have before another storm hit, destroying whatever they had managed to repair? Velma made up her mind. A few days after the inspector visited the house, she bought three one-way tickets to Seattle.

When Velma told her mother that she was leaving, Dolores protested. “But your family’s here. We can do this together,” she said. Velma knew that her mother often told people, “Velma is my pillar. She is stronger than I am.” At Christopher’s funeral, after the motorcycle accident, Dolores had asked Velma how she could be so stoic. “I looked at her and said, ‘Mom, I have no choice.’ Because I could see it in their eyes. If I fall, everybody’s going to go with me. I had to push myself up.” This time, however, Velma realized she had a choice. “I just needed to get well—physically, mentally. I felt so sick.” She told her family, “If I stay here, I’m going to die.”

The night before Velma and Henry left the island, the family ate dinner under a palapala—an awning Velma’s brother-in-law, Bill, had patched together with scraps of tin. He had enclosed the dining area with a low wall of cinder blocks, on which Velma’s sister, Carleen, had arranged dozens of pots blooming with desert roses. The storm had stripped the island’s trees of leaves and fruit, turning the jungle brown, but Carleen’s gardens had been growing back quickly with mulberries, basil, and dragon fruit. Carleen begged Velma not to leave—it made no sense to her that her sister would abandon her house in its broken state, let alone her older daughter—but Velma had made her decision. “It pained me to leave,” she later said. “Honest to God, when I left my house, I didn’t want to look back.”

From left to right: Doris Joseph cooks dinner with her family; a photograph of Velma Del Rosario’s son, Christopher, and religious icons in the remains of the family’s house.

On February 9, 2019, Velma, Henry, and Analina arrived at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport during a historic winter storm. Velma slept through the entire shuttle ride to Junie’s house, where she went on sleeping for several days, waking finally to the world glowing white, to her body loosened by relief.

Velma had lived on the mainland before. In 1986, when she was eleven years old, Ronald Reagan granted citizenship to people born in the commonwealth, and Velma acquired a U.S. passport. As a child in Saipan, her world had been the farm, where she spent her days gathering fallen fruit for pigs and herding cows to fresh pasture. Her grandmother had kept their home neat—a compulsion, Velma believed, rooted in the Japanese occupation before World War II, when officers would inspect houses and torture islanders who failed to meet certain standards of cleanliness. Ana had been a devout Catholic; every morning at four-thirty, she and Velma had walked to mass. But above all else, Ana valued education, which she believed was the sole method by which Velma would transcend her family’s poverty. In 1989, the two of them moved to Las Vegas to live with a relative so that Velma could attend high school there. But Ana found that she hated the desert. “It’s so dusty,” she would say. “What kind of place is this? You can’t even plant onions, and you can’t even raise pigs. Everything you have to buy.” After Velma had been in Las Vegas for two years, Ana convinced her to come home.

Back on the mainland thirty-two years later, Velma applied for Medicaid and enrolled Analina in school, while Henry found a job at Goodwill. She saw a doctor, who diagnosed her with arthritis and hypertension and prescribed medication. Her pain subsided, and she began moving around more easily. They found a routine again: Henry cooked breakfast, then Velma drove him to work. If she felt like cleaning, Velma cleaned. If she lacked energy, she watched TV. Velma had always drawn a paycheck and felt self-conscious without a job, but Junie didn’t mention it. They liked to make jokes and laugh together. Junie worked from home, so Velma tried not to get in her way. When spring came, she spent time in the yard looking at the birds, or she went driving, familiarizing herself with the local roads. On weekends, Velma and Junie cooked Chamorro food and took Analina to the beach.

Whenever Velma looked out across the Pacific toward Saipan, she felt relief, but also guilt. She spoke every day to Christylynn, who was tending to their property. “There’s no life in this house,” Christylynn told her one day. “I said, ‘What do you mean there’s no life?’ ” Velma recalled. “She said, ‘You guys are not here. It’s such a lonely place.’ ” Velma missed Saipan—her family, the beaches, the fish her brother-in-law caught and fried for dinner. But she had chosen to leave, and now she resolved to stay.

At first, Christylynn told herself that her parents were on a long vacation, but the ruse lasted only so long before the reality of their departure sank in. Velma and Henry had always been there to help her; now Christylynn felt vulnerable and alone, bearing the burden they had left behind. She had her mother’s truck, and with it her mother’s monthly payments. There were also her student loans, on which she owed $9,000, though the stress of the typhoon had forced her to drop out, since she suddenly had no place and little time to study. Columbia Southern University, where she was pursuing a degree in criminal justice, would not let her resume classes until she paid the bill in full.

When Velma left Saipan, she had given Christylynn power of attorney in all matters related to the house, and now Christylynn had weekly calls with a FEMA representative named Mary who had been assigned to the family’s case. Among the FEMA programs the Del Rosarios qualified for was one called TETRIS, through which the government distributed thousands of tents and installed temporary roofs on homes across the commonwealth. A TETRIS crew had arrived at Velma and Henry’s house a few weeks after they left. Christylynn had been living there, under the tarp, and when she returned from work that day, she found the new roof hastily done. She assumed the crew would return the next morning, but it didn’t. The roof remained unsealed. Rats crept in. One night, Christylynn woke to a rat nibbling on her toe and kicked it across the room.

In March, Christylynn showed the house to another FEMA inspector. FEMA had begun implementing a program called Permanent Housing Construction, which was designed to repair or rebuild houses according to new building codes, making them likelier to hold up during future typhoons. The inspector had been tasked with identifying low-income families whose homes had sustained at least $8,000 of damage. Since Velma was no longer employed, the inspector told Christylynn, the Del Rosarios might qualify. “You’re going to have new windows, a new roof, shutters,” he said. “I’m really going to try to help you out, okay?” Later that month, Christylynn received a call from Mary, who told her that they had been accepted into the program.

The news buoyed Christylynn, who was now living with her boyfriend in a tent on his mother’s property in Kagman, seven miles north. Summer arrived, and with it another typhoon season. Whenever a storm approached, Christylynn and her boyfriend collapsed the tent, packed their belongings into her truck, and sheltered in a hotel until the rain stopped. Those days, while stressful, were a respite from their sweltering tent. Mold marbled the inner canvas. Christylynn sometimes found herself struggling to breathe, a problem that she ascribed to allergies and anxiety. One day at work, her boss noticed her having a panic attack and sent her home.

Christylynn knew she was not the only one whose anxiety had mounted since Yutu. Her aunt Carleen had lost her entire house and was now living in a makeshift shack that would certainly blow away in the next typhoon. A FEMA-funded initiative called the Crisis Counseling Program had dispatched local aid workers to speak with survivors about their mental health. Many survivors said they were afraid of the next big storm. The workers observed high rates of depression as well as a rise in alcohol abuse, domestic violence, and suicidal thoughts.

In October, a year after Yutu hit, Christylynn learned that another super typhoon, Hagibis, was headed for Saipan. She and her boyfriend packed up their tent and checked into a hotel. The day of the storm, she shot a video of the wind and rain and sent it to her mother. Velma told her not to send any more videos. “My heart can’t handle that,” she said. Hagibis just grazed the island. But one night later that month, Christylynn returned home to the tent after work, sat on her bed, and began wheezing. Her boyfriend brought her to the fire station, where an EMT called an ambulance. Christylynn was uninsured, a month shy of the enrollment period for her job’s health plan. That day, her out-of-pocket medical expenses amounted to more than $800.

Carleen and Bill Joseph at their family compound

Each winter, during the Lunar New Year, resorts in the Northern Marianas fill up. The beaches are flush with tourists who park pastel-colored Mustangs at the water’s edge, lounging like sphinxes on the hoods. Most of them stay in Garapan, where the Imperial Palace Saipan casts a shadow over the town. But it is not easy to hide economic inequality on an island. Just six miles south of Garapan were the villages hit hardest by Yutu—Chalan Kanoa, San Antonio, Koblerville, Finasisu, and Dandan—where vast numbers of residents were still living in tents.

In Dandan, a Chamorro woman named Janice Celis was staying with ten relatives in her mother’s house, since many of them had lost their own homes in Typhoon Yutu. For a while, Janice’s brother Roy had also lived on the property, in a tent with his wife and kids, but a few months after the storm, FEMA began offering families transportation assistance to leave Saipan until the island could recover. “The storm was hell,” Roy said. “No power, no water. I thought we might as well move, because we don’t have a place to stay.” FEMA had booked his family on a flight to the mainland in February 2019.

The plane was full of families relocating through the same program. “We were all asking each other, ‘Where are you going?’ ” Roy recalled. The other families were moving to California, Arizona, Texas, and Washington State. They spent a night in Guam, and then split up in Hawaii. FEMA paid for Roy and his family to live in a hotel in Portland, Oregon, for three months, until Roy found a job stacking lumber and was able to rent an apartment. That April, FEMA bought Roy a return ticket to the commonwealth, but he stayed only three weeks, to clean up his property, then went back to Oregon. He missed the island, he said, but he doubted he would live there again. He was tired of the typhoons. “I don’t want to experience that anymore.”

Roy was in the minority. Only 154 people—fewer than 2 percent of those eligible—had left Saipan with FEMA’s help. This did not account for people like Velma Del Rosario who, for myriad reasons, paid their own way. But most storm survivors had been reluctant to abandon their relatives and property. For one woman in Chalan Kanoa, Tricia, the thought of having to go through a super typhoon again made her want to leave, but she was not sure leaving would lessen her burden. Tricia knew a family who had accepted the FEMA plane tickets, and “their move wasn’t as smooth as they thought it would be,” she said. They struggled to find jobs, and, unable to support themselves, were considering returning to the island.

Living with the threat of worsening typhoons was stressful, but moving to the mainland and leaving behind one’s family—for many storm survivors, their sole safety net—seemed riskier. “It’s not the same as here, where you have family around,” Janice, Roy’s sister, said. “There, you’re homeless if you don’t work.” There was also the fact that many islanders primarily spoke Chamorro or Carolinian, which made moving to a place where almost no one knew their language even more daunting. In other words, it took an enormous disaster to convince even a few people to flee.

Meanwhile, FEMA was investing in repairing and rebuilding homes. It had broken ground on the Permanent Housing Construction program in November 2019. Amid tents, tin shacks, and piles of debris were houses sporting shiny roofs and fresh coats of paint. But while 876 households qualified for PHC, only 303 were enrolled; most had opted out after realizing they could not afford to wait years for FEMA to build them a new house. Instead, they were offered either an SBA loan or a grant of no more than $37,000 to make repairs themselves, which meant that hundreds of houses would still be as vulnerable to extreme weather as they had been before Yutu.

Among those still waiting for repairs was Christylynn Del Rosario. One morning after the Lunar New Year, she sat on a patio by her tent in Kagman, dragging on a cigarette and apologizing for the smoke. She wore athletic shorts and a tank top; that afternoon, she would put on her uniform and go work a shift at the airport. Rain fell, drumming like fingers on the tent. “It gets hot in there,” Christylynn said, “but I don’t like to sit out here either. Cars pass by and I think, Oh, they’re going to think I’m lonely.” She took as many shifts as possible to avoid spending time in Kagman. If she needed company, she went to the compound to visit her relatives. She was feeling hopeful that FEMA would start work on her house soon. She had considered asking the TSA to transfer her to the mainland to be closer to her parents, but now she wondered whether a repaired house might sway her parents to return. “That’s a lot of what we talk about,” she said, “how life is going to be in the future.”

From left to right: School damaged by the storm; the western coast of Saipan.

For the Northern Mariana Islands, storms are not the only long-term vulnerability. Robbie Greene, a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who is stationed in Saipan, believes the commonwealth’s greatest challenge will be maintaining its water supply. As climate change causes sea levels to rise, salt water could be drawn up into wells. The islands could also see longer droughts as small typhoons become rarer. FEMA will spend $817 million on the recovery from Typhoon Yutu, reimbursing the commonwealth for roughly 90 percent of its expenses. But FEMA is a disaster-relief agency; it is not equipped to address the more systemic problems plaguing the islands. Some have begun to wonder how much longer residents of the commonwealth can hold on.

Among FEMA administrators, “resilient” has become a popular word. They use it to describe the houses they’ll fix, the electrical grid they’ll secure, and the shelters they’ll build. They use it also to describe the indigenous islanders who, they say, know better than anyone how to survive a storm, how to thrive under difficult circumstances. They use it to explain why so many islanders, when offered the money to leave, chose instead to stay. They use the word so often that one begins to wonder about its meaning. Sure, another typhoon will come and blow away the tin houses, and people will again spend years in canvas tents and beneath tarps, slapping at mosquitoes and kicking rats and waking every hour to sweep rainwater from their floors. Sure, it will happen again and again, FEMA officials say, and people will suffer, but each time the commonwealth will come back stronger, more resilient.

But humans are not infrastructure. They get worn down, tired of having to rebuild their lives. Calling islanders resilient is like saying “You can take it!” while neglecting to interrogate why they have to in the first place. Asked whether the islands’ status as a U.S. territory made them more or less vulnerable to climate change, Tina Sablan, a legislator for one of Saipan’s hardest-hit districts, said that the commonwealth could not have financed its own recovery without FEMA, and yet “we have a president and administration that is actively seeking to roll back laws and regulations that are supposed to be addressing climate change.” She noted that commonwealth citizens cannot vote in presidential elections. “So in that sense, I think we are more vulnerable,” Sablan said. The government responding to the commonwealth’s emergencies was the same one ensuring that they would continue to occur.

Amid all the talk of resilience, the fact remained that some people had chosen to leave, and more would follow. “I think this will be a place that folks don’t want to live long before it becomes a place that’s unlivable,” said Greene, the NOAA scientist. It was not that Typhoon Yutu had made the islands uninhabitable; it was that some people, through an accumulation of trauma, had decided they could not bear to live there any longer. There would be no single catastrophic event that caused everyone to flee at once. Rather, long before ocean swallowed the land, people would trickle out, one tired family at a time.

Velma and Henry visit her cousin in Henderson, Nevada

In October 2019, Velma, Henry, and Analina left Washington and moved to a suburb north of Las Vegas, into another relative’s guest bedroom. “Junie wanted us to stay,” Velma explained. “But I told her, ‘Junie, I have to move, because I don’t think I can afford this place. I’ve already been here seven months.’ ” Junie tried to persuade her to change her mind. “I don’t care if it’s until next year,” she said. But Velma was firm. “You guys have done enough.”

While Velma and Henry searched for new jobs, they relied on food stamps, Henry’s Social Security check, and their relatives’ generosity. Since they had no money for gas, they left the house as seldom as possible, passing their days chatting with family in Saipan and submitting job applications online. Velma had given up on applying for social-work positions. Instead, she applied for a janitorial job at a casino, but no one called her back. The family was bored, and Henry had begun suggesting they go home. It had been a year since they’d left the island, and they had recently received good news: An inspector from the PHC program had discovered cracks in the walls of their house and had deemed the entire structure unsafe. The Del Rosarios now qualified for a new house, worth $120,000.

But that also meant they would have to wait even longer for construction to begin. According to Mary, the FEMA caseworker who still called Christylynn routinely, it was possible that the project would not be finished until 2022. Without a secure house, Velma had no interest in returning to Saipan. She was hopeful that she and Henry would soon find jobs in Las Vegas and be able to afford their own apartment.

Still, Henry was becoming more insistent. At least they owned land on the island, he reasoned, and they could get their jobs back. Henry missed the quiet of the family compound. There, whenever he and Velma argued, he liked to go outside and sit beneath their mango tree. “My husband is like the water,” Velma said. “He puts me at peace. He goes under the mango tree, and I say, ‘Hey, boy, did you count how many mangoes will be ripe tomorrow?’ He laughs.” In certain ways, Velma admitted, life had been easier in Saipan: “You’re not worried about getting evicted, because you own the land. Even if you don’t have money, you can do so many things. I visit my friends; they feed me. People say, ‘Velma, can I pick the breadfruit?’ ‘You can take the whole damn tree.’ You harvest today, tomorrow there it is.”

One day earlier this year, Velma video-chatted with her family on the island, who were preparing a picnic under a palapala by the beach. Bill smoked ribs and grilled garlic as Carleen arranged a table with red rice, corn, and finadene, a sauce made of lemon juice and salt. There was a hole in the palapala where a tree had punched through during the typhoon, and when it began to rain, water poured onto the table. Then the rain stopped, and Bill smiled. “When it doesn’t rain, it doesn’t leak,” he said.

Velma’s relatives passed the phone around, panning the camera across their feast. Velma found it hard not to notice everything she was missing. That night, the family would return to the compound, where the adults would drink and dance and play ukulele while the children raced their tricycles in the street.

Scientists are often careful to say that it’s impossible to connect singular events like Typhoon Yutu to climate change. Similarly, it’s hard to blame just one storm for setting islanders like Velma adrift. But this is the complicated nature of climate change: it slowly alters the reality we inhabit, changing the people and places we have always known, so that all we can expect is uncertainty.