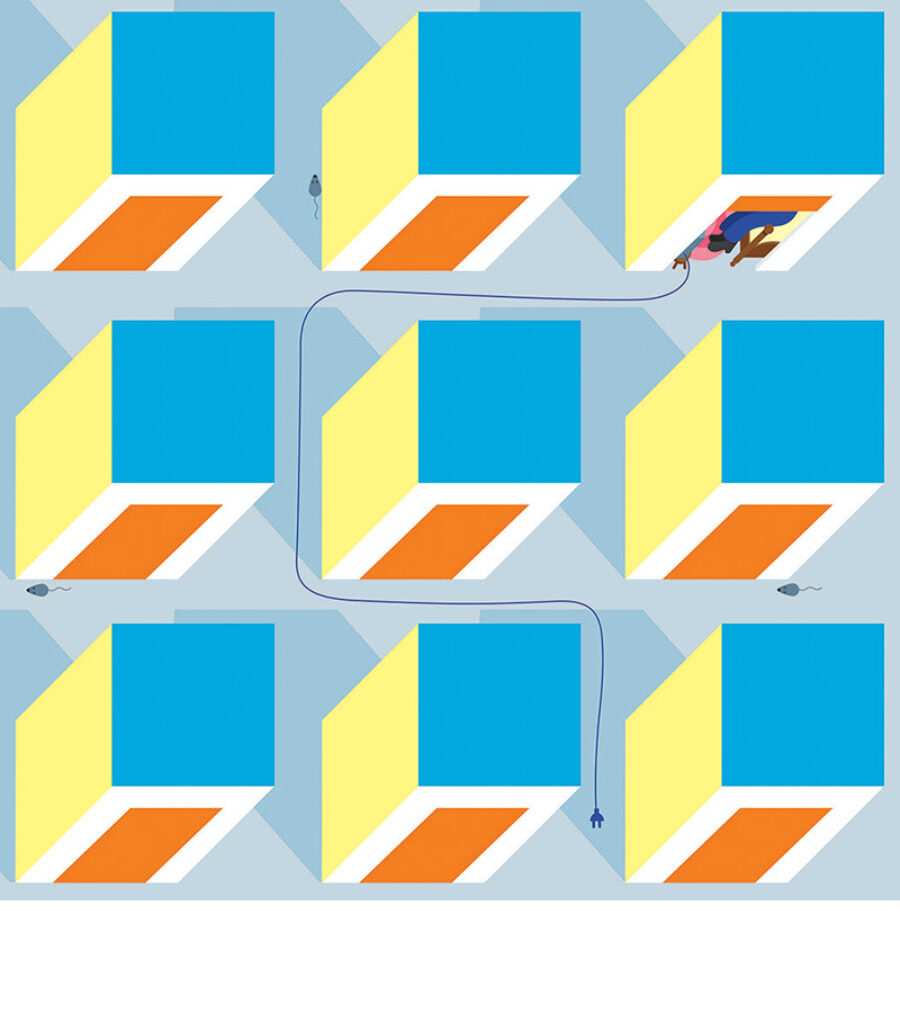

Illustrations by Melinda Beck

The term “self-storage” was coined by analogy with “self-service,” but the analogy is flawed. You can pump your own gas at the station, wash your own clothes at the laundromat, scan your own groceries at the supermarket; but, as those who cannot resist the gag have pointed out, you cannot store yourself. (Some combination of municipal code, state law, and company policy will always forbid it.)

We rent a storage unit in a building three blocks from our apartment, in Brooklyn, near the East River. The building is surrounded on three sides by an electrical substation, and there is nothing else on that street, which is the last street before the water and is only a single block long. By late March, the staff is uncertain whether the facility will remain open as an essential business under emergency public-health orders. So a few hours before those take effect, we go to the unit to collect any items that could prove desirable or useful over however many months the building might be closed.

Years ago, at a Texas storage facility outside town and near the airport, one of us came across a man who sometimes lived in his unit on the sly. The units were all outdoors, just rows of roll-up shutters. The management locked the bathrooms at night, the man said, and made sure the water temperature of the faucets was unpleasant for sustained use. The man said he wasn’t homeless, though people who live in their units usually are; he ran a business out of his, something that accounted for the dense assortment of equipment hanging on the walls and involved a lot of metal grinding. They didn’t bother him about running an extension cord for his tools, and he just liked to sleep there sometimes.

It was in Texas that self-storage originated, in the 1960s. The industry has flourished since then, and the United States now has 2.5 billion rentable square feet, at least 90 percent of such space in the world; over the same period, the average size of an American single-family home nearly doubled, and the average number of occupants fell by a quarter. This suggests that self-storage was not an inevitable convenience but something else, perhaps an indicator of national psychopathology.

A significant minority of tenants wind up renting for longer than they intended. And nearly a quarter of likely new renters say they plan to use their personal warehouse space for items they “no longer need or want.”*

For others, with better-sounding reasons, it is often not the premise but the execution that is the problem. As long as I am living far away but planning to move back; as long as it takes my new spouse and me to decide how to consolidate our belongings; as long as I am sorting out my divorce; as long as I need to find a buyer for this treadmill. These all make sense, but “as long as” is circular. What easily happens is that the logic of the original limit transforms, maybe imperceptibly, maybe banished from conscious thought, and the deadline recedes before us. Reasons have expiration dates, and good reasons go bad. The metal-grinding man in Texas, with an enduringly sensible explanation for his tenancy, was a model of logical demand, and actually a business tenant, not a consumer. For him, storage was a monthly expense with specific and appreciable benefits. The language of tenancy familiar from leases, use and enjoyment, rarely applies to the storage premises, and almost never to what is stored there long-term.

The business of self-storage—which on its face seems clean and efficient and uncomplicated, even liberating, a rational approach to commodifying personal space beyond the immediate confines of the home, tinged with the buoyant midcentury prosperity of its birth—can become a perverse kind of trap. Of course, many people make bad and unexamined financial choices; many collect junk; many put off decisions. But the storage unit can make those problems discrete, cognizable. The reason reality shows about hoarding flourished a decade ago, the critic Scott Herring has argued, is that hoarding was a special case in which the larger culture tipped into definable deviance.

With perhaps a few terrifying exceptions, it is rare to calculate the portion of one’s mortgage or rent going to the corner of the garage covered in piles of boxes. The separateness of the storage unit permits an observational experiment.

In late 2009, one of us bids on and wins a number of items at the dissolution auction of a small aerospace-parts manufacturer in Long Island City. The most impressive things on offer are the enormous drill bits—which create a queasy sense of scale that turns humans into Disney mice, with diameters up to five or six inches, all of them won by a South American shipbuilder—or else the giant rotary table worth thousands of dollars with an asking bid so low it is essentially free. (To whosoever can move it: like a tempting but cursed object sold to a dupe in a fairy tale.)

An antique steel workbench and a steel cabinet with fifty-five tiny drawers will be powder-coated white, given places at home, and used well. But the rest of the things—Czech lathe chucks and Swedish carbide inserts, Japanese reamers and German probe gauges, American micrometers and English punch sets—are for nobody in particular.

The exact plan for these items has been deliberately forgotten, but they are transported with help from a man with a van and no teeth, and wind up in a disused part of the basement of the building in which we live, though only one of us lives there at the time. A few months later, the absentee landlord makes a rare visit to town and enters the disused part of the basement. He demands back rent for its use. The building manager, an old Normand, explains that this area needs to be kept clear, in case the landlord moves to town and needs a place to live. (The room has exposed insulation tufting out of the ceiling, which is no higher than five feet above the crumbling concrete-slab floor. On a civilized patch of tile stands a lonely but functional toilet. The neighborhood rats, which have two points of entry, decline to use the space.)

Another man with a van—actually a gentle, dreamy boy with a truck, with which he later accidentally kills someone near Penn Station—helps move the objects out of the basement and into the storage unit, which has just been acquired, on a month-to-month lease, for this purpose. Some of the items are slowly sold off, and two years later, another young but less dreamy entrepreneur, who has put himself through college with an eBay business (selling rare Red Wing boots and horse-leather coats that turn up in barns after old Midwestern farmers die), takes over, bulk-selling on commission. But having made only a little headway, he moves back to Minnesota to put himself through law school (selling old books from thrift shops). He leaves behind two simple aluminum reflector lights, which make it easier to see.

The other of us is then in grad school with relatively formless days and little income, and the next summer agrees to take over where the second young man left off, for a larger cut of the sales. The more valuable things go quickly, after which the outflow becomes a trickle. In the fall of 2014, a man named Gregory emails: “I can provide a good home,” he says. “I will meet your asking price and take the whole lot off your hands.” And he does, even the makeshift shelving.

In India, where one of us grew up, self-storage remains unknown; or if known, it became so recently, and one of us has been behind on the news. Everything surfeit went to the property’s godown. (The word broadly means “warehouse”; it looks like an English compound, and sounds like the Negro spiritual, but the Europeans took it from Malay and bestowed it on the subcontinent, whence the Malays first took it.)

Absent things were often said to be in the godown, but the will to retrieve something and the ability to locate it seldom coincided. Sometimes the godown would flood or have termites. Morning coats and top hats would be rediscovered far beyond any hope of repair. For decades it contained the childhood things that had belonged to one of us, and then, maybe twelve or fifteen years ago, according to some unknown schedule or an impromptu expression of household virtue, one morning these were hauled out into bright winter daylight, doused with kerosene, and burned.

This godown was an oubliette. Not the medieval trapdoor storeroom reimagined as a diabolical dungeon by romantically inclined novelists of later centuries, but a literal “place of forgetting,” of things half thrown away. This slipping of inanimate objects into oblivion echoes those holdout cultures in which the clinical standard of death (hypoxia, brain death, cardiopulmonary arrest) is not a hard line but part of a continuous process, through which we descend from being a little dead (decrepitude or illness) to more dead (at death’s door) to mostly dead (the body cools and is buried or otherwise disposed of) to very dead (mourning and celebration have concluded and time has passed).

The memory palace was a technique used from antiquity to the Renaissance that made it possible to retain numerous pieces of information by committing each one to a discrete location in a three-dimensional structure held in the mind. Although the printing press, by reducing the difficulty of storage and retrieval, made the technique less vital, the memory palace is a tool so powerful that it has been devised spontaneously, up through the present day, by people who have never heard of it. The storage space is in a way its opposite: a discrete physical place where things—often with no precise order or inventory—are relegated out of sight of the mind’s eye. Things go there to be forgotten.

At a sorry corner on our storage building’s block, surrounded by wire-fenced, gravel-covered utility-company land, junk regularly appears from the storage units.

In the summer of 2014, the corner featured a continually refreshed array of fabrics. In the fall of 2015, sewing supplies. In the late spring and early summer of 2017, a miniature wine fridge, a black bathroom shelving unit, a leather hand mirror with a damask elephant on the back, hair extensions, a Habitat for Humanity teddy bear. The next winter, hair rollers and the book Scram: Relocating Under a New Identity.

This stuff stays for a few days or a few weeks, nobody’s problem. Rain and snow dissuade most anyone feeling the tug to salvage anything, until some unknown power comes and takes it all away.

Many of the things left at the sorry corner are manifestly ugly or useless, yet it should not be assumed that this always represents the true dross, that all the promising stuff was taken. Tenants moving items in or out have carts stacked with empty CD towers, cardboard boxes full of worn-out polyester blankets, an elegant mannequin designed to be headless but also missing its intended arms, a third-place high school track trophy, a lamp made of a taxidermic pheasant glued to a tree stump finished with green pool-table felt and veneered ears of wheat, and, separately, a lamp whose glass base encases a grouse, likewise with ears of wheat.

Storage facilities make dumpsters and other garbage receptacles scrupulously scarce, less because of illegal dumping by trespassers than to keep tenants from realizing, when moving, that they do not want everything they have. On varying arcs, what is stored may long have been on a trajectory toward becoming trash.

Judging by the volume and variety of goods on the corner, it sometimes seems that the entire inventory of a unit has been disgorged. Delinquent tenants’ possessions (as we know from another reality-TV genre: shows about storage-unit buyers) would have been auctioned off and responsibly disposed of. The dumpers were paid-up. Or perhaps someone arriving at the building ready to take out a lease had second thoughts and rolled right on down the single-block one-way street, looked to make sure nobody at the electrical plant was watching, and made a fresh start of things.

“In its countless alveoli space contains compressed time,” wrote the philosopher Gaston Bachelard. “That is what space is for.”

Often, with a storage unit, you are not renting space. You are buying time.

The journalist Jon Mooallem, writing about the self-storage industry in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, wondered whether it would continue to benefit from the “kind of psycho-financial inertia that has kept so many tenants in place.” (It did.)

Picture a coordinate graph. Time x versus money y, with a horizontal line at a certain y value that represents not only the worth of all the goods stored but also generously includes the value of all the labor it would take you to acquire their equivalents all over again. For many people, it would be hard to abandon ship even as time went by and the cumulative cost of renting crept upward across that line. As money becomes time, time itself becomes sunk cost.

Think of another graph. The x-axis is still just the unalterable fact of time. But the y value represents some combination of hassle, perceived or actual usefulness, regret, hope, etc. As the first graph grinds on, this graph, tracking the willingness to keep going, comes to look like exponential decay. You could say this graph reveals the half-life of attachment.

“If you guard things so scrupulously that you put them into cold storage,” wrote the art critic Robert Nelson of Andy Warhol’s practice of warehousing every piece of paper he received in the mail, “you cross over into another kind of psychopathology—for you will never open the boxes, much less read the dated typeface. The papers may as well be in the bowels of the pyramids, as if consigned to an eternity that may be gratefully glimpsed one day by someone searching for gold.”

Gregory, the man who takes everything and gives it a home, should be the end of the storage unit. All that remains is a valuable hardness tester excluded from “everything,” an empty bulk cat-litter bucket filled with ivory piano keys, two metal Ikea table legs, and an old black cloth suitcase missing a wheel.

But that same week, one of us leaves office work for good. And after we finish clearing out his office in Manhattan in the middle of the night—not the night that requires loading up a borrowed car with books and papers and “office” clothes and so on, but the night after—we take a taxi back over the Manhattan Bridge. The storage facility is visible from the roadway. The driver is a South Asian man in late middle age who has been doing this job for some time. He says that twenty-five years ago he would drive over to this very neighborhood with file boxes from law firms, delivering them to a warehouse right under the bridge. He was poor at the time; had he money then, he swears, he would have bought property here. He was certain even then that it would all change from storage space to commercial and residential. The area was too close to downtown. There was nowhere else to expand.

The unit is four feet wide by ten deep. The walls are corrugated steel (we checked with a magnet), with sparse steel studs, and the ceiling, which is too impractically high to think much about exactly how high it is, is wire mesh. There is electrical conduit running over the outer walls of the units, and a rare outlet appears right above the door to ours, so that an extension cord can be run inside.

In goes the good desk chair from the office, and a seasonal-affective-disorder lamp. Then a folding card table is found whose top, fully unfolded, fits precisely between two opposing concavities in the sinusoidal ripple of the walls.

It seems unusual that a single storage unit should be the site of more than one folly. And yet the cost of renting it might be redeemed by realizing a new purpose—an office space—that would not have been discovered without the original folly. After all, renting a desk in the neighborhood would cost at least three times what the unit does. This extravagance of frugality accounts for maybe five or six hours of useful work over the subsequent half a year.

We disagree about who had the idea for the next stage, but deep down we both know it was one of us.

The following summer, 2015, there is a trip to Jetro, a restaurant wholesaler (it is like Costco but far, far more dangerous), which then still unofficially allowed members of the public to shop and so was thronged with Bangladeshis and Hasids who all drove Toyota Siennas, the preferred car of Brooklyn “ethnic” families who need to transport more than five members at a time. This is followed by a trip to Trader Joe’s, where the cashier, counting all the bottles of white balsamic vinegar and bags of quinoa—the former providing the clue that this purchase is not for something big but for something long-term—asks whether it is for the apocalypse. There is a Whole Foods trip, from which the last box of whole wheat fusilli was just used, five years later. A five-pound bag of red pepper flakes appears, as does a flat of tuna, a flat of chickpeas. All this bounty is now right down the street; it is easier to retrieve things from there than it is to walk to the store. Relatively little of what goes in is descript or personal—a collection of LPs, lamps from old Pullman passenger cars, degrees that were framed without our consent. It is, we tell ourselves, a sensible, logical use, not a conflicted, emotional one.

Shelves are found to hold everything. Tall white enamel metal ones from a startup in what used to be Jehovah’s Witness file storage, which are fitted inside the unit one evening just as the building is closing, with great effort and much fighting, owing to the hypotenuse problem, which is often forgotten. A wobbly stamped-metal one found out on the curb, chrome wire ones from the former office. Some wretched, half-broken fiberboard ones advertised on Craigslist that turn out to be located in our storage facility, on the same floor. A set scavenged from an apartment the other of us lived in, built of scrap wood and cheap modular steel components.

At some point the other of us declares that the office thing is over, this is all storage or else it is folly, and takes the chair to the office where she has recently started working. This gives the space a narrow central passage with shelves of different depths and widths obtruding variously all the way to the back of the unit. Moving through it feels like being inside a video game dating from the clumsy period of transition between two and three dimensions.

The mother of one of us has rented a storage unit in Texas since she moved there, in the late 1980s, at the facility where the grinding man sometimes lived. It is the size of a snug one-car garage and perhaps one-third full. It contains many tin trunks whose locks no longer have keys. The trunks contain books, papers, and textiles, and probably other things too. Perhaps the long-lost notes Ted Hughes wrote about her dissertation on Sylvia Plath. (Years later, she once told one of us, in a university archive she was accidentally given Plath materials—containing a close antagonist’s taunt, “Why don’t you kill yourself again?”—which were supposed to remain sealed for decades, and were hastily confiscated and returned to storage.)

In 2015, she began renting a second, smaller storage unit, in a climate-controlled building near the center of the city. She had heard about the workstation one of us had set up in New York and was inspired to try it, though she did not acquire a desk or a lamp. The staff told her she was not allowed to leave a storage space empty. As a result, or maybe this plan was percolating anyway, she thought she would use the space as a staging ground to triage papers that had overwhelmed her at home, or to sort possessions that were in the unit out toward the airport.

Things from the far unit would be brought to the near unit, things from the near unit would go to the far unit, things from the house (or from the storage shed attached to the house) would go to and come from both, and the near unit would always contain some minimal number of things that could go nowhere, because of the rule that you cannot store nothing. This mise en abyme was never realized. Late last year the managers had a problem with the card on file and could not get in touch with the tenant, so they called the authorized party named on the rental agreement, which was one of us, who on learning of the persistence of such an agreement went to end it. (She has not allowed the closing of a secure locker in India, which is now, unhappily, in the name of one of us and at last inventory contained a bottle of cognac and a pile of cash.)

The placeholder boxes of papers had never been touched, and went back to the house. The rent came to $12,000.

One day, the very optional sign-in sheet in Brooklyn records only one tenant, Shadow Zill, who elsewhere can be found only as a registrant in a Queens bowling league, and whose name is just the same word in English and Arabic. Another day, the sign-in sheet shows that the tenant occupying the unit to the right of ours is a woman one of us has known for a decade. He does not mention it to her.

We get an extra month free if we prepay the rent a year at a time. And so we do. It would be insensible not to. You can, indeed, freeze the rent at current levels, forestalling future increases, for any additional months you prepay beyond those thirteen. That we never do; it would be insane.

The building changes ownership. The three-location chain is taken over by a national one, and they replace the faded five-story vinyl banner on the side of the building with a fresh, sickly green one, like an iPhone sent-as-SMS text addressed to Manhattan. They surround the banner with high-output floodlights. These shine into one of our back windows at night. The neighborhood email list grouses about the glare. The other of us calls the company and tells them that there’s a problem. “Oh,” they say, “we’re sorry, this is the first we’ve heard about that. We’ll look into it.” Now the blinding LEDs selectively face the East River at night, and when it’s very late they all shut off.

The tiny parking lot closes for some sort of makeover. The oldest, most ornery handcarts are replaced by newer ones with smooth wheels and inflatable tires. But the structure is irredeemably ancient, from the Taft Administration, and cannot be made to behave like the climate-controlled, cleanly designed storage buildings going up now. The passenger elevator still breaks down frequently, and then it is necessary to take the stairs or the shuddering old freight elevator, which uses a manual throw switch, so that the operator has to estimate when to stop for the desired floor, and is often off by six or eight inches. The nonmotorized doors on each floor must be pushed open and pulled closed from the top and bottom, and the number for each floor is spray-painted on the shaft side of those doors, like temporary markers that became a permanent solution.

Under the old management there was a squat, apoplectic Trinidadian—a charming and fickle Indian buffoon from early V. S. Naipaul. He is replaced by a choleric, more professional West Indian, a lean black man with a faint, unplaceable accent.

“You have kids?” he asks us as the freight elevator slowly rises.

We say no.

“Late bloomers,” he says.

Millennials, it is often reported, are uninterested in their boomer parents’ abundant accumulated possessions. Might this hurt the storage industry? They also have the highest storage use of any generation, with one fifth of households. (Millennials, and city dwellers, are also likeliest to choose the inscrutable survey response of having “personally experienced” “living in their units.”) Another idly theorized threat to the storage industry is the success of Marie Kondo’s book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. The idea seems dubious: consumer storage use recently reached 10 percent of U.S. households, and if anything threatens the business, it would be the pandemic, which appears to have spawned vacancies and depressed rents. It is plausible, however, that a number of Americans attempted a Kondo purge—getting rid of possessions that failed to spark joy, often thanking them for their service before relinquishing them—but wound up storing those things. Since Kondo’s sensibility derives from both Zen’s ideal of nonattachment and Shinto’s respect for the animate dignity of the “inanimate” world, it would be an acute irony for these objects to become imprisoned, like the diverse species of Japanese undead, in a state of irresolution.

In October 2017, there are 112 bars of nice chocolate, not including baking bars and bags of chocolate chips. These result from a series of reductions at a store called Closeout Connection, a mostly downmarket (now defunct) clearance center for household overstock hidden underground across the road from Brooklyn Borough Hall. The chocolate is eaten quickly, but because the unit is not air-conditioned, the rest travels to the office of one of us, which lately, like most commercial real estate in New York City, sits unused, until its lease is canceled and the contents are moved to a Manhattan Mini Storage.

There are also several bottles of delicate old vintage port, an expensive gift, and these make a graceful seasonal migration from the unit to the refrigerator’s crisper drawer.

In Stephen King’s novella The Langoliers, the characters travel through a tear in the fabric of the universe and wind up not in the past—the familiar science-fiction past that is alive with possibility and depth—but in spent time. The air is still, the sounds are dull, the beer is flat, the clocks have stopped.

Although the experience of time’s duration is unrecoverable, its ghosts can be reanimated by the persistence, allure, and rediscovery of objects in space. A pressure cooker on a cabinet above the stove, unread books on medieval art from a university course stuffed into a childhood bedroom, the crockery set inherited from an aunt. But when such objects are gathered together without context, we perceive the absolute flatness of time lived and lost, of life displaced.

A perfect incarnation of one type of storage would collect together all the guilty, festering objects from all the spaces in one’s life and concentrate them in flat, spent time and neutral space. Many storage tenants do this, to some degree. It is a place that does not hold the past in some straightforward balance between preservation and deterioration. It can hold the past as well as the future—that is, a past life to which we may hope to return, or objects with little connection to our past lives but essential to an imagined future, to improvement, or at least to change. It is a place of aspiration.

Letting collections of things perpetuate in this way creates both a memento mori and a refusal of death’s power: American storage-renting is the opposite of Swedish death cleaning. Even the anonymous surplus of items with no emotional valence can be considered a form of aspiration, namely, the disposable consumption that has cost us the world.

We never keep inventory with any discipline. (The cloud document “Storage Unit Inventory” appears last to have been updated in 2017.) When leaving the house, one forgets to check for all the consumables that might be found in the unit; when in the unit, one forgets what is needed in the house, and goes home to find the dish soap nearly finished or now in excess. And so it becomes necessary to relax and just find what may be found.

We forage OxiClean, rubbing alcohol, deodorant, paper towels, contact solution, jars of peanut butter, mustard, canned tomatoes, capers, vitamins, chicken bars, coffee beans, sardines. Soylent—a product from a movie made real as a joke, and then made a startup-culture punch line—is consumed at a rate of about one bottle every eighteen months by one of us demonstrating to the other that buying it was the right decision. Some of the things begin to expire, but an expiry date on something that’s sealed is a suggestion, after all, not a rule, and often wildly, irresponsibly conservative. The pure cranberry juice has retained its taste but turned clear; a case of Shiner Bock has gone flat. The great quantity of wine and liquor makes scant sense, as we entertain little and drink even less.

At the urging of one of us, we decide to start living like normal people, which means we stop using the storage unit as a pantry. When we need something, we will just go to the store. That is what normal people would do. So we allow the nuts to dwindle. The shredded coconut dwindles. The booze does not dwindle nearly fast enough.

As we begin this drawdown, a year ago, a flange manufacturer in Texas buys the hardness tester off eBay for a little over ten times its purchase price. This is a Pyrrhic victory. It is a heavy and unwieldy steel contraption that would destroy regular packing materials, so one of us builds a crate for it using wood repurposed from an Ikea dresser left on the sorry corner in the rain.

Economics makes various attempts at pinning down the psychological trickiness of the future. One model holds that there is no special mystery to thinking ahead; it’s just that you need to factor in every possible risk beforehand, and time will lose its power. This degree of clarity is one of those things that might be approximated only by the voracious AI of data capitalists; it’s totally out of reach for imperfect, striving individual actors.

A lack of self-knowledge is as much a problem as a lack of perfect empirical knowledge. Sunk cost and other perceptual fallacies tie us to the past, and we “discount” the future, but because we discount the future we can also place outsized bets on it. A storage unit invites fallacies about both what has been and what is yet to be: the aversion to abandonment, the commitment to keep going, the unreality of the future. This is closer to the vision of those behavioral-economics researchers who acknowledge that our best current selves will not necessarily make the choices our best future selves would want us to have made. We, the common people, understand this uncertainty; it is why we hold on to iffy things. You are never the same river twice.

At home there is a go bag: a backpack squirreled away for some nameless disaster. The idea of a go bag is that you could leave home in a hurry, in exigent circumstances, and have a range of basic useful things without needing to think about and search for them. Ours contains cash, protein bars, stocking hats and thermal underwear and regular underwear, photocopies of important documents, flashlights, charging cables, a solar charger, a hand-crank radio, a sewing kit, toiletries, utensils, knives, Mylar blankets, a camping towel, various first-aid supplies, various medicines. The protein bars are very old and the status of the batteries is unclear. The ibuprofen is fine but the antibiotics have presumably gone off. One of us pillaged the cash at one point, and we have not resolved whether he replaced the correct amount. There is no stay bag. (Unless, the storage unit.)

All insurance is essentially against a future we do not want. It is a hedge against the principal commitment. But there can be perverse incentives, and among serious preppers there is a persistent strain of romanticism and optimism. The lack of pessimism in their fatalism (doom without gloom) goes like this: The properly prepared person will be all right, will have all he needs, will flourish; it cannot turn out to be so bad that this will not be possible, or there would be no point in preparing.

Such people tend to own the property where their supplies and shelter are located. It would be a fairly mild form of societal collapse if all the storage facilities were still running smoothly. Understanding this is, at last, the reason we stop keeping all those foods and toiletries there.

Which is not to say the unit is done with. Many things are still there. Fresh, unworn pairs of running shoes, unwieldy snow boots. The LPs, a turntable. Two small prototype desks, in ginkgo and black walnut, made by a furniture designer friend. In the summer, there are winter clothes and rugs. There are antique thrift-shop frames awaiting art of the right proportions. There are many lampshades, ranging in age from 120 years to a few months old, and an antique dental lamp (to be sold), and an antique wooden medicine cabinet, crudely constructed but with beautiful stepped art deco hinges. An unmanageable, irreducible amount of liquor. The small secondhand window air conditioner whose acquisition one of us finally permitted after years of insisting that air-conditioning was a degenerate indulgence. The plastic case for a spare power sander that’s still listed for sale on Craigslist. Pieces of printed fabric from a designer’s sample sale and a wool factory’s odd ends, mostly for having clothes made, save one enormous bolt that was offered as upholstery fabric to a friend only to learn he had just downsized—having decided he could do with half the space and having sold off most of what had occupied the other half (a dining-room set and statuary, a Balinese opium bed and a red cut-glass chandelier, etc.)—and started renting out the vacated bottom floor of his house to a boutique, and then died. Cases for sunglasses and glasses, some containing the demo lenses of old prescription frames, a pair of sunglasses that were a gift for the friend who died, second-tier luggage waiting around for transatlantic flights with a two-checked-bag allowance, clothes to be sent on such journeys for repairs or alterations too complex to do cheaply in the United States, the piano keys, a box of scrap maple, the copper-bottomed steel kitchenware that belonged to a grandmother of the other of us, the spare crockery for a future kitchen (on land in the country? or in a bigger house?).

When we go there in March to get the things, commingled with these, that we might actually need sometime soon, we are unable to proceed. The unit to the left of ours is open, and a set of huge concert-size speakers is blocking our door. The tenant is coughing, loudly and dryly. One of us goes to get masks—which have for years, and with different purposes in mind, been stored at home.