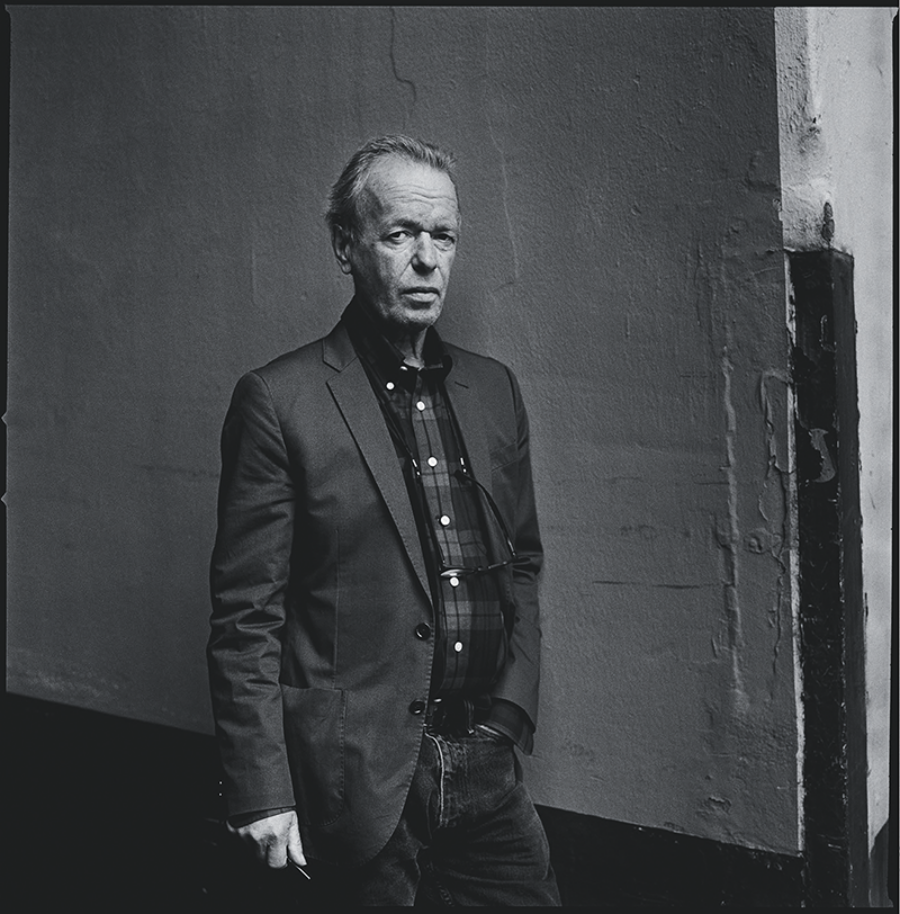

Martin Amis © Gunter Gluecklich/laif/Redux

Discussed in this essay:

Inside Story: A Novel, by Martin Amis. Knopf. 560 pages. $28.95.

While Martin Amis’s most gifted contemporaries—Salman Rushdie, Ian McEwan, Graham Swift—were rebellious in technique, borrowing from magical realism to consider questions about identity, Amis’s achievement might be described as primarily tonal. In his early novels, he worked toward the invention of a new literary dialect, a mix of slang and poetry, concertedly swaggering, at times a little singsong, insolent but ebullient, exacting yet loose, eager both to comment and to evoke, a cascade of ideally weighted adjectives and nouns and participles. Here…