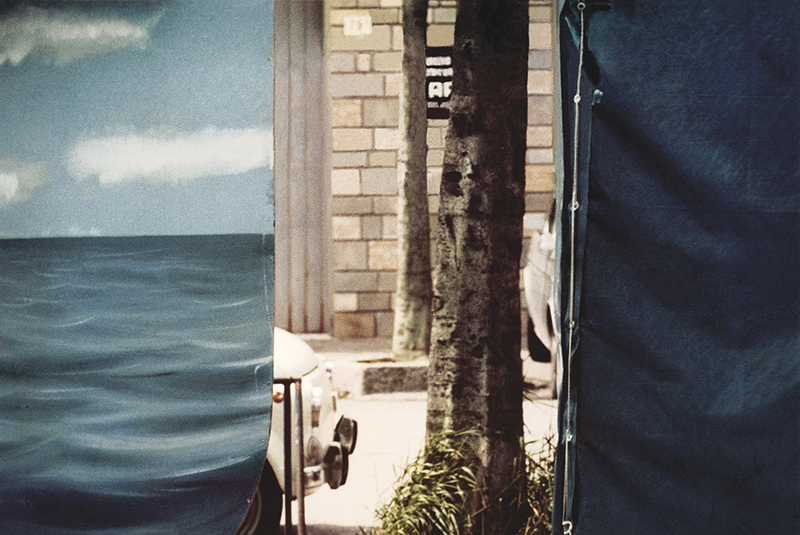

“Modena, 1973,” by Luigi Ghirri, from The Map and the Territory, which was published in 2018 by MACK © The artist. Courtesy MACK

It has been oddly comforting these past few weeks to read a novel about living in total isolation after an inexplicable, catastrophic event causes the entirety of Earth’s population—save for one very concerned narrator—to vanish. Dissipatio H. G.: The Vanishing (NYRB Classics, $15.95), by Guido Morselli, translated from the Italian by Frederika Randall, is a useful reminder that things can always get worse. Morselli died by suicide in 1973, shortly after the book was rejected by a publisher—the seventh manuscript of his to meet that fate. As Randall dryly notes in her introduction, “Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that the novel itself begins with a suicide, a suicide deeply desired but finally thwarted.” (Sadly, Randall, an accomplished political journalist and extraordinarily lucid translator, herself died in May of this year.)

The question of whether or not the narrator’s suicide is, in fact, thwarted seems to be an open one, not least to the narrator himself. What pushes him over the edge—his trigger, as he calls it—is his discovery of a plan to build a “continental motorway” through the rural valley where he lives, outside the city of Chrysopolis, a European banking center that sounds a lot like Zurich. He plans to drown himself in a remote cave, but, while enjoying what he intends to be a few final sips of Spanish brandy, finds himself feeling “strangely, unshakably well” and decides to keep living. Then he hits his head on a protruding rock—“a powerful blow”—and thunder rumbles nearby. He goes home and toys with the idea of shooting himself, his mouth pressed to his “black-eyed girl.” When he wakes the next morning, the world is empty.

What follows is less a traditional novel than a series of brilliantly despairing philosophical disquisitions, pegged to the narrator’s wanderings through abandoned streets, airports, and hotels. We wait for him to find a companion, to hear a crackling SOS over the radio or discover a message left behind, anything to set a plot in motion. But instead he contemplates a travel poster for the Bahamas and thinks, “The death-prize, like collective tourist emigration, makes sense in a century like our own hugely dedicated to the improving activity of travel.” He smashes a shop window to steal some grapefruit and reflects that anarchy has finally prevailed through the abolition of private property, even as “a monarchy has been installed, in the most elementary meaning of the term: all power to one man.” He starts wearing women’s clothing, not for “autoerotic” purposes, he insists, but because they “don’t weigh on you this time of year.” (This doesn’t really explain the stockings, garter belt, and “gigantic lacy panties,” but: no justification needed.) In essayistic digressions that voluptuously condemn the decadence of modern civilization, complete with copious references to imagined or embellished Latin sources, Morselli makes the case for himself as a cantankerous shared relation of Huysmans and Houellebecq.

One of the narrator’s monologues finds him “in a search for lost time, which on the whole, whether it involves recovering distant or recent experience, offers me little.” The reference is deliberate, at the very least on the part of the translator: one of the two books Morselli managed to get into print during his lifetime was a study of Proust. That this was possible even for poor Morselli is a reminder of the seemingly limitless appetite for Proust criticism, the highlights of which range from Samuel Beckett’s recursive philosophical essay in 1930, to the lectures Józef Czapski delivered in a Soviet prison camp during the Second World War, to The Albertine Workout, Anne Carson’s fragmentary reflections on the elusive love object of Proust’s great novel. Now joining this august company is the Israeli historian Saul Friedländer’s charmingly ramshackle Proustian Uncertainties (Other Press, $25). Friedländer, a lauded expert on Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, describes his short book as an essay, and notes at the start that he is no specialist on Proust. Indeed, the pleasure of the book comes from its old-fashioned, amateur quality, the author unspooling thoughts and venturing theories collected over many years about a book he clearly loves.

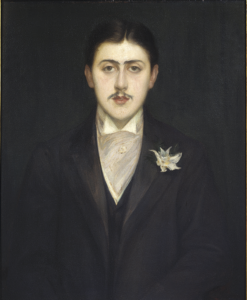

Portrait of Marcel Proust, by Jacques-Émile Blanche © Photo Josse/Bridgeman Images

Friedländer is most interested in “the question of identity,” and scrutinizes various discrepancies between Proust and his narrator—Proust was Jewish on his mother’s side, while the narrator’s family does not appear to be so; Proust had open (for the time) relationships with men, while his narrator does not—without coming to definitive conclusions. Whether because Proust was anxious of too much self-revelation, or was simply dividing himself judiciously among his creations, as many great novelists do, he suppressed these characteristics in the figure that most outwardly resembled him. But he made his most memorable and fully realized characters—Swann, Bloch, Saint-Loup, Charlus, and Albertine—either Jewish or gay. His own conflicted relationship with those aspects of himself made these characters come alive.

By taking a bird’s-eye view of the novel, Friedländer notices continuities and contradictions that are hard to see from within the teeming thickets of Proust’s prose, or that of C. K. Scott Moncrieff and his successors in English. He points out that, though the first volume famously opens with the narrator recounting his obsessive love for his mother and his fear of his father’s anger, “nowhere in the novel do we learn his parents’ names, nor do we get even a hint of their physical appearance.” The decline and death of the narrator’s grandmother is justly considered one of the great depictions of illness in literature, but his parents simply disappear “without a trace.” Friedländer saves the revelation of his own traumatic connection to Proust’s work until nearly the end of the book, as he struggles to understand why he chose to write about À la recherche du temps perdu.

Throughout my life, I haven’t remembered the pealing of any garden bell . . . as happened to the Narrator, but just an immense pain that as a memory never left me: the memory of my last meeting with my mother and my father, at the age of ten, in the hospital room in Montlucon where they were hiding, in September 1942. All of that never occurred to me as a reason for writing about Proust’s Recherche, but maybe this was it.

After that final goodbye, his parents were murdered at Auschwitz.

For Friedländer, there was a measure of solace in setting aside the exigencies of the historical record to explore some of literature’s great unanswerable questions. The fiction writer Danielle Evans, meanwhile, has taken the opposite tack in her new novella and short story collection, The Office of Historical Corrections (Riverhead, $27). In the title work, she imagines an underfunded bureau of the federal government called the Institute for Public History, which is dedicated to rectifying incorrect statements about the past wherever in the United States they may be found. In an early scene, the novella’s protagonist, a black IPH investigator named Cassie, patiently explains to two bemused employees of a cake shop in Washington that, contrary to the flyer taped to the counter, Juneteenth does not celebrate the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, but rather the date almost three years later when slaves in Texas learned they were free. “You gonna buy a cake?” one of them asks after Cassie has finished her lecture.

Encased Cakes, by Wayne Thiebaud © The artist/VAGA at Artists Rights Society, New York City. Courtesy Sotheby’s

The Juneteenth correction serves as a prelude to the significantly more fraught assignment Cassie takes on later in the novella. The IPH sends her to fictional Cherry Mill, Wisconsin, a small town northwest of Milwaukee, where a dispute has arisen over a plaque memorializing the death of a black man who was reportedly killed when a mob of white citizens burned down the building he owned in 1937. Apparently, the man may not have actually died, in which case the plaque, which also names the members of the lynching party, will have to come down. But standing in the way of an easy resolution is Genevieve, a rogue former member of the IPH (and Cassie’s lifelong frenemy) who has set up camp in Cherry Mill, and whose overzealousness in correcting the historical record has thrown her life into disarray. You may not be surprised to learn, if you’ve read a newspaper in the past five years, that the Free Americans, “a group of white supremacists who preferred to be called white preservationists,” are also circling the plaque controversy, with guns.

In the wrong hands, the marshaling of so much sociological material risks didacticism, a morally salutary but lifeless march to a preordained conclusion. But Evans is interested in the nuances and contradictions of the characters she depicts. She wants to understand the messy, contingent processes through which history is created, and her curiosity and empathy extend, throughout the collection, to characters buffeted by personal and political crosswinds. “Boys Go to Jupiter” follows a college student named Claire who, after posing for a photograph in a Confederate-flag bikini at the behest of a winter-break fling, finds herself the center of a campus controversy. Rather than making Claire a caricature or following through on the parable of cancel culture that the story first appears to be, Evans slowly reveals the layers of Claire’s past, particularly the intense bond she once shared with her childhood neighbors in Virginia: two black siblings, Angela and Aaron, whose mother, like Claire’s, was fighting cancer. Claire’s mother dies, and a rupture follows, Claire withdrawing into substance abuse that leads, indirectly, to Aaron’s death in a car accident. These revelations are not meant to excuse the character’s callousness, but rather, through Evans’s subtle but firm guidance, to help us understand it.

Eagle, by Ralph Griffin © The Estate of Ralph Griffin/Artists Rights Society, New York City. Courtesy Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta

Like Evans, the sociologist Matthew Clair allows us to see seemingly familiar, politicized phenomena in a new light. His new book, Privilege and Punishment: How Race and Class Matter in Criminal Court (Princeton University Press, $29.95), is a careful study of what he argues is an overlooked cause of inequity in the criminal justice system: the unexpectedly combative relationship between defendants and their lawyers.

Clair studied the experience of sixty-three defendants in the Boston court system, roughly sorted into two categories: those he calls “privileged defendants” (“middle-class people of all racial backgrounds . . . and white working-class people”) and “disadvantaged defendants” (“working-class people of color . . . and the poor of all racial backgrounds”). Privileged defendants, who had little experience being on the wrong side of the law, were likely to defer to the expertise of their lawyers, trusting them to advocate effectively on their behalf. Disadvantaged defendants, though often imagined as passive cogs in the machine, were in fact more likely to question and resist their lawyers’ strategies. This was often, Clair found, due to previous adverse experiences with the justice system. But the reasons varied. To a privileged defendant, for whom “the costs of lost dignity in court are not as grave when dignity is readily afforded to them in their everyday lives outside court,” a plea bargain, even in an instance when the defendant may not feel at fault, is often a desirable outcome. For disadvantaged defendants, however, the opportunity to set the record straight could itself constitute “a form of substantive justice,” one that can lead these defendants to refuse or resist deals proposed by their lawyers, who are (understandably) encouraged to focus on the endgame.

That resistance, Clair found, led in turn to conflicts with counsel that jeopardized the outcomes of their cases. Lawyers, frustrated with their clients’ unwillingness to follow advice, sometimes insisted on transferring them to other public defenders, further alienating the defendants. Judges, too, with packed schedules and rigid rules of courtroom conduct, were often unsympathetic to defendants’ desire to make a case for themselves in court by, for example, attempting to file motions against their lawyers’ instructions.

Clair’s point, simply put, is that the system should take more care to understand defendants’ lives and circumstances. A court that was, for instance, able to see why certain defendants might choose a short prison sentence over a longer period of probation—which requires the defendant to hold a full-time job but often makes it hard to do so—would be more widely trusted, and thus more likely to produce better outcomes. Though the solutions he proposes are of varying plausibility in the near term (from public defenders actively connecting their clients with social workers and housing and immigration lawyers to abolishing, or at least declining to enforce, laws regulating drug use, sex work, and homelessness), Clair has done a significant service simply by reframing the issue. As Morselli’s dystopian vision reminds us, things can always get worse; but with enough small interventions like Clair’s, they can slowly begin to get better too.