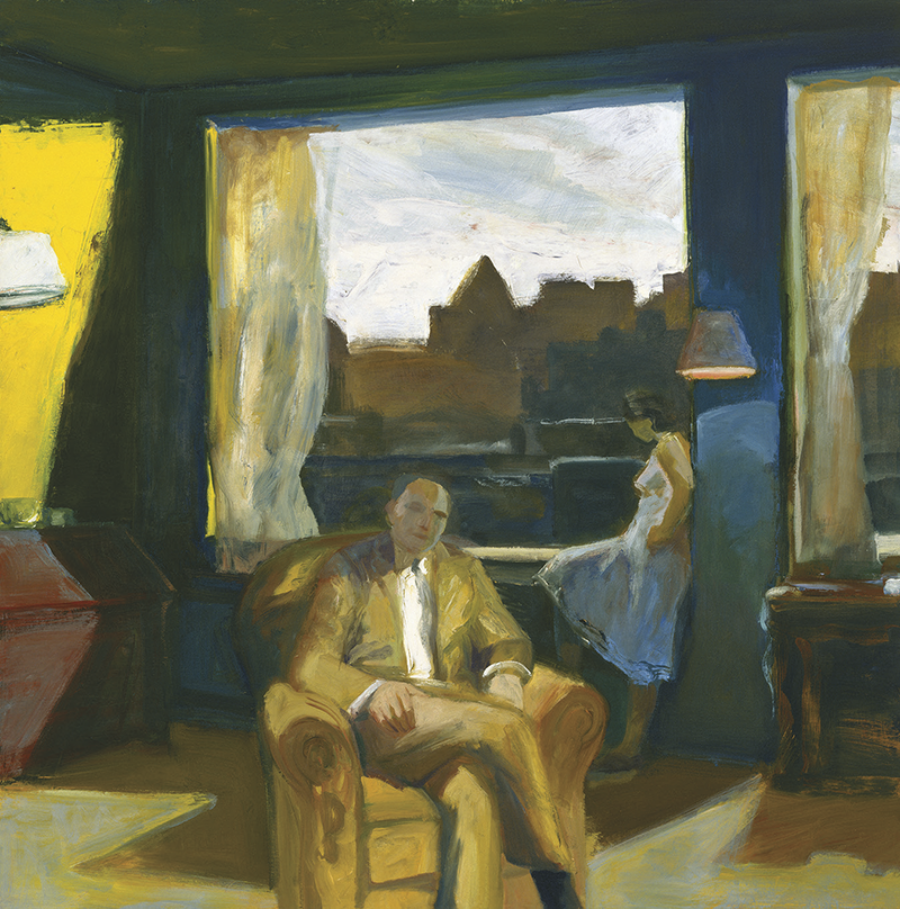

Interior with Two Figures, 1968, a painting by Elmer Bischoff. Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Alice Pratt Brown Museum Fund © The Estate of Elmer Bischoff. Courtesy George Adams Gallery, New York City

Discussed in this essay:

In Love, by Alfred Hayes. New York Review Books Classics. 160 pages. $14.

My Face for the World to See, by Alfred Hayes. New York Review Books Classics. 152 pages. $14.95.

The End of Me, by Alfred Hayes. New York Review Books Classics. 192 pages. $15.95.

Alfred Hayes’s novel In Love opens with a man sitting in a New York hotel bar, talking to a young woman in the middle of the afternoon. “Do I appear to be a man,” he asks, “who doesn’t know what’s wrong with him, or a man who privately thinks…